The problem that I saw was not in whether or not Pixar could pull it off. I knew that they could. They had an amazing track record. They would be willing to invest the time, energy and resources into making sure the film hit all of the right notes. If they could make people cry over toys and monsters then a story about deceased family members would be a given. What I saw as a problem was the cultural element. There were thousands upon thousands of things that people think about when it comes to reflecting a culture. Having advisers was a good start but for just about every studio that was also where their cultural immersion ended. When the worlds were fictional, say Monsters Inc. or Cars, then people weren't really up in arms about it. Pixar could make up anything they wanted about these worlds and nobody would protest. But as soon as they took on a real holiday with layers of religious and cultural overtones then people (especially minorities) were right to have their concerns.

The Christian observation All Souls Day did not really conjure up any specific images in pop culture. If you hear the words El Dia de los Muertos however, then the visions of candy skulls, painted skeletons and colorful altars immediately come to mind. Some people mistakenly liken this to Mexican Halloween. It is actually a celebration of family ancestors that is quite humble and solemn. Most didn't realize that the holiday was centuries old and the skeletal imagery was pulled from ancient traditions. There were ceremonies in the Pre-columbian world to honor the dead, two versions of these native holidays were combined by Catholic missionaries when All Souls Day was introduced in Mexico. The colors and symbols used no international artist could ignore. In small chunks the holiday had been appropriated by directors that had little to no understanding of its roots. Dia de los Muertos was used as set dressing for the films Spectre (2015) and Batman v Superman (2016). In which the Mexicans were voiceless actors parading around in a not-quite-right version of the holiday. In more pandering ways it had been stripped of its true meaning and used as a way to sell lottery tickets.

When I first saw the California lottery tickets earlier this year it felt like a slap in the face. It was as if the lottery commission was saying to me "Hey stupid, this is your culture and we are selling it back to you $1 at a time." It felt as if our holiday had been appropriated by the USA. The people with the power were taking something that wasn't theirs and repackaging and selling it for mass consumption. It was how I felt when I heard that Pixar wanted to make a Dia de los Muertos film. I wondered how an animation studio that wasn't based in a Latin community, that had never created a short, show or film about the Latin community and was not lead by any Latin directors could take on such a project. It was great that they were interested in the holiday but there was so much nuance to it that I feared that Dia de los Muertos was becoming the new "Tiki."

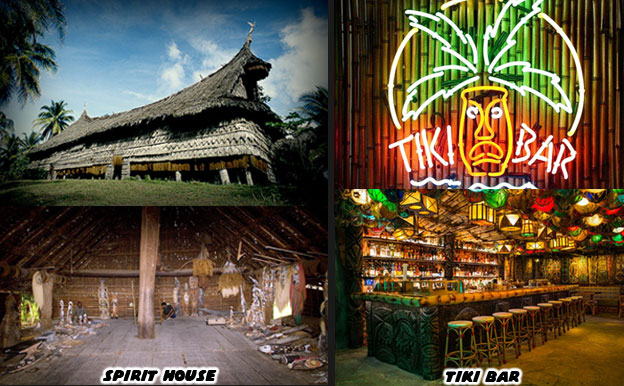

When soldiers came back from the Pacific Islands post WWII they created a caricature of the Oceanic Arts. One in which the mythology, art, architecture, design and landscape of the islands, minus the people, were idealized. Ancient symbols, community gathering places and ancestry worship were stripped of their identity. Ornate carvings in koa wood were made squiggly lines in drink coasters, handmade tapa cloth gave way to plastic grass skirts and ceremonial totems became bottle openers. The spirit house became the bar within a generation. Ask somebody from New Zealand, from Papua New Guinea, from Samoa or Hawai'i what they think about tiki culture. They'd say it had as much to do with their people as Taco Bell had to do with authentic Mexican food. To the mainstream US however, there was no difference between the two.

Little by little the symbolism behind Dia de los Muertos had come up more in mainstream culture. It had been incorporated in bite-size pieces. A costume or mask for Halloween. A coloring book and a sticker sheet found in the grocery store. A label on a beer bottle. They were small, innocuous at first. But as more artists, designers and art directors learned about the culture the more they began to "tiki-fy" it, to mass produce the cultural icons and slap them on all sorts of products. Before you knew it there was an entire section in the World Market dedicated to Dia de los Muertos. There were invites at Party City, sweaters in Target and of course lottery tickets all featuring the same sugar skulls and papel picado. I had little to no faith in Hollywood would ever get this right but then The Book of Life came along.

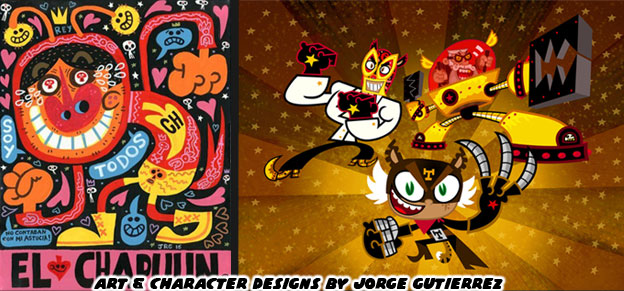

The film from 2014 was not only a breath of fresh air. It was also a validation of our people and our culture. It didn't appear overnight. The writer and director, Jorge. R. Gutierrez, had been building a name in the animation industry for years. He had spent at least a decade, along with his talented wife Sandra Equihua fine tuning the story and characters featured in the Book of Life. His artistic style, incorporating elements of Mexican pop culture and art was established early on. His characters didn't look or sound like anything on Western television. His voice was unique in the industry and could be counted on to add an element of authenticity on animation featuring or about Latin culture. Jorge had built a following with shows like ¡Mucha Lucha! (2004), Maya & Miguel (2006) and El Tigre: The Adventures of Manny Rivera (2007). As a native Mexican Jorge had an insight and appreciation of the culture that the vast majority in Hollywood would never understand. His (and his wife's) brilliant designs aside, his comedic timing, his pacing, the ability to insert subtle details about masked wrestling, dramatic supervillains and the occasional churro nobody else in Hollywood could reproduce.

Everyone that I knew, Mexican or not, loved the Book of Life. When Disney and Pixar announced that they too were working on a Dia de los Muertos animated feature many fans were up in arms. An amazing film had just come out celebrating our culture, written and directed by "one of us" and we couldn't own it for longer than a minute. It was frustrating. Jorge had spent half his professional career on getting it off the ground. He had poured his heart and soul into this project only to see the biggest animation company in the world come along and cash in on the momentum. It was something that stood out when Coco Director Lee Unkrich asked why people felt threatened by Coco: It was obvious to fans that he simply didn't "get it." On paper the plot of both films was very similar, a boy longed to be a musician and his family forbade it, then he reconciled this with the help of his deceased relatives Yet that was only one level to the frustration.

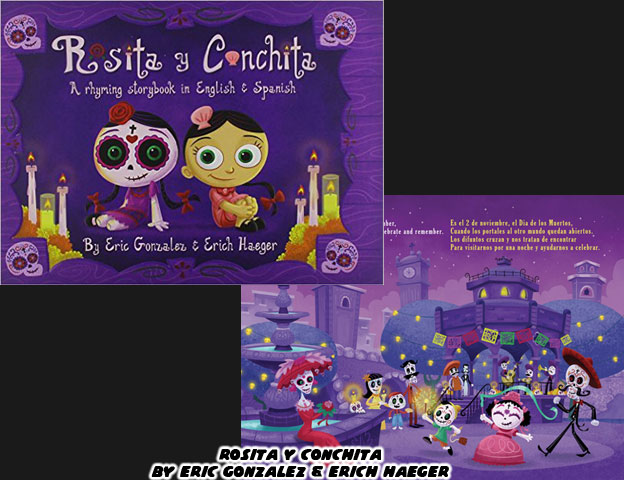

Visual stories featuring el Dia de los Muertos had been around for a while. One of the best was Rosita y Conchita (2010) By Eric Gonzalez and Erich Haeger. Eric was similar to Jorge in that he was known for his fantastic illustrations and 3D pieces featuring styles and themes reminiscent of traditional Mexico. Gonzalez was a staple on the comic convention circuit and pop art shows. He went on to create Muertoons (2014), featuring Rosita and her friends. The animated skeletons went on adventures and learned timeless lessons about family and friendship. This was something that was the crux of both Book of Life and Coco. Family that was not forgotten lived on forever in the land of the dead. In Book of Life the Apology Song (If you can forgive) was sung by Manolo. He begged forgiveness for the countless forgotten bulls that were slaughtered by his family. He also had to return to the land of the living before his town was wiped out and no one would be left to remember them. In Coco the song "Remember Me" had a similar effect. Being remembered was the most important thing for those that had passed on. You would have thought that Pixar had created something new if you didn't know that the Muertoons title song "Not Forgotten" was sung by a rebellious young guitarist named Bibi.

Not only was Pixar coming into the culture late, but they were riding on the coattails of other filmmakers already developing and producing films about the holiday. When Disney applied for the copyright on Dia de los Muertos they didn't realize there was another animation studio already working on a similar project with a similar name. Dia De Muertos, the Mexican directed and produced animated feature by Metacube that was in production before Coco. It wouldn't be released before Coco came out but that didn't stop the small studio from battling, and defeating Disney in court. There was also a computer-generated film about a girl reuniting with her mother during Dia de los Muertos. The 2013 short by Ringling College of Art and Design students Ashley Graham, Kate Reynolds, and Lindsey St. Pierre won a Gold Medal at the Student Academy Awards. In 2006 Laika animator and Texas native Kirk Kelley produced a stop-motion short on the holiday as well. Pixar would certainly gain the lions share of the attention, critical acclaim and profits from their film but they were far from being the first studio to tell a story set in the culture.

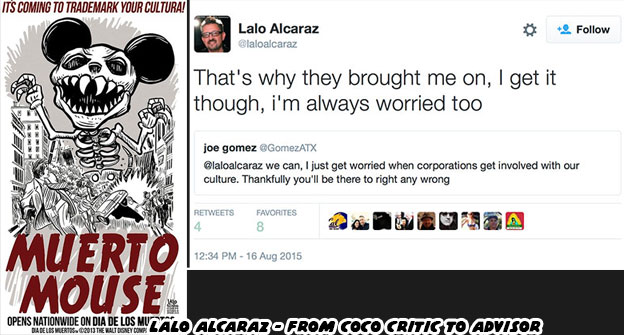

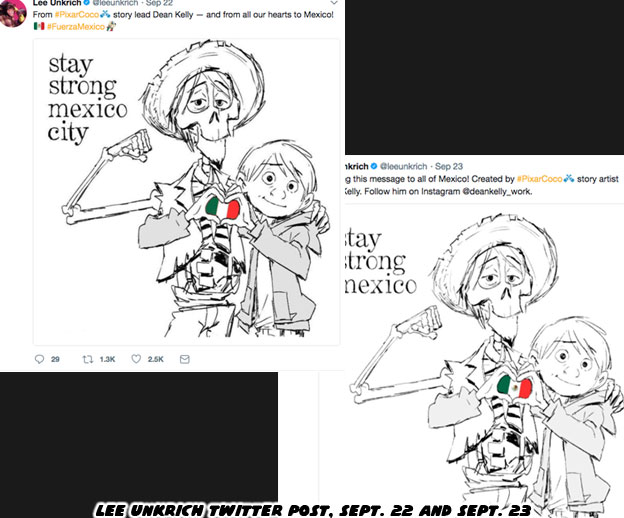

The blowback that Disney and Pixar generated when they originally announced their film made their approach more cautious. They began doing things for the film that they had never done on previous projects. Not only did they hire consultants and take trips to Mexico but they also began screening scenes to these outsiders to gauge if they were being sincere, authentic and respectful of the culture. The Latin community represented almost 39% of California's population and 17% of the US population. In an age where the President of the USA said that Mexicans were sending rapists and murderers across the border the pressure for Pixar to get Coco right was tremendous. People were very critical of every real or perceived misstep from the studio. When Central Mexico had an earthquake on September 20th the nation didn't expect any condolences from the North. On September 22 Lee Unkrich shared a picture on Twitter featuring Miguel and Hector from his film. The drawing was credited to story lead Dean Kelly. There was just one problem.

The tiny flag in between the hands of Miguel and Hector was not Mexico’s. The colors were right but it was missing something very important. The eagle and serpent, a story from native legend stretching back more than 600 years was supposed to be at the heart of the flag. Fans called out Unkrich on Twitter and they said the Italian flag was a nice touch, but maybe next time there was a disaster the studio might bother to get the flag right. Unkrich updated the drawing a day later with the new detail. It wasn’t drawn in but looked more like a rushed photo edit. Dean Kelly was then credited as a story artist instead of a story lead. Also in the original post it was about Mexico City but the earthquake had affected many more towns than that, so the repost was changed to read just Mexico. It made many wonder how a studio that had supposedly spent years and years on a project, had brought in outside consultants and had actually traveled to Mexico forgot about the places they went and even the details on the national flag.

It was these things and more missteps from Hollywood that were under my skin before Coco ever came out. Mexico was presented with a surface level understanding by most animation studios. When Coco was announced and the plot revealed my mom asked if all Mexican boys wanted to be guitarists. I responded that there were only three stories that the studios could tell. They could make a film about Dia de los Muertos, mariachi music or masked wrestling. Choose any two and make a movie about it. Anything past those three occupations was unrealistic. Heaven forbid there would be a movie about a Mexican girl that wanted to be an astronaut. When some studios created a Latino character they almost always went with the ugliest caricatures of the culture. One of the worst things I ever saw in film was El Macho in the film Despicable Me 2 (2013). The villain, whose real name was Eduardo Perez was the owner of the Salsa & Salsa restaurant. Not only was he an excellent dancer, but he was also very macho you see. He was as absurd as was his son Antonio, the stereotypical latin lover. The audience laughed but I winced as the same tired jokes about Latinos were used over and over again.

Mexico had a complex identity and it was hard to capture that on film. Spain and France helped the US defeat Britain in the Revolutionary war, they were thought of very highly in US history books. At the same time those two nations had also carved up and colonized Mexico and Central America. The people in Mexico did not necessarily favor the way they were treated by the Europeans. There was a tremendous Pre-Columbian identity in Mexico that was almost wiped out when Spanish Catholicism was introduced. The native culture did not mix easily with the European. There was a sharp contrast in the old and new if you were to look at art from 500 or 600 years ago. One minute there was a thriving indigenous population, worshiping ancient gods and the next there were oil paintings of Christ suffering on the cross. There was no transitional period, nothing to bridge the two worlds. That came later, when holidays like Dia de los Muertos evolved.

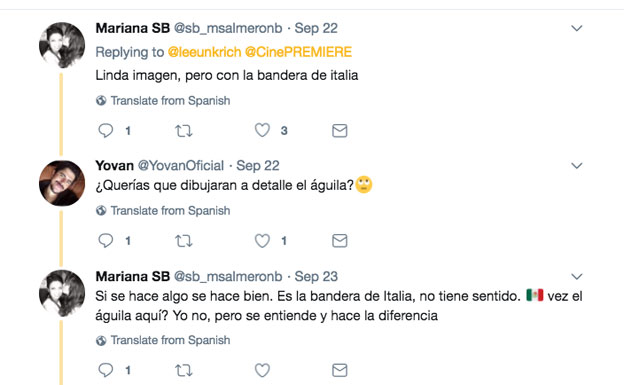

Even masked wrestling had roots in the ancient world as well. Back when war heroes and generals wore animal skins and headdresses that made them appear like eagles or jaguars. The popularization of masked wrestling, some 80 years ago helped bridge ancient and modern traditions. The character El Macho was created out of ignorance. He was just one of several abrasive parodies of Mexico's fascination with masked wrestling.

I knew that Unkrich and probably most everyone in Pixar didn't know or understand how something like masked wrestling took over Mexico. How it became part of the national identity. Sure it was easy to present in a film. It could even be used for a quick, throw-away gag. But masked wrestlers, enmascarados, represented good and evil. Every match was a morality play. The good guys, the technicos, played by the rules and were held to a high standard. The heels, or rudos, could only win by deceiving their opponents or colluding with a referee. If you looked at the top heroes and villains you could actually identify who was who. The angels were the good guys and the devils were the bad. There was nothing ambiguous about it. There were no anti-heroes that skirted the line. It was easy for crowds to cheer for the good guys and jeer the bad. Kids knew who they wanted to be. They emulated their heroes, they played with their action figures and watched their films. Putting on the mask was akin to a comic book fan putting on a cape. It was transformative.

Once there was a drug addict that was saved thanks to wrestling. He became a priest and fought to stay sober. He used the gimmick of a wrestling friar to help raise money for his parish and orphanage. Fray Tormenta (Father Storm) became a cult hero and later national hero for his dedication to the craft. He went so far as to actually perform his priestly duties while in character. There was nothing more than an awkward comedy of the man, of the culture and of rural Mexico by the time Napoleon Dynamite director Jared Hess was done filming Nacho Libre. El Macho was cut very much from the same ignorance about Mexican wrestling. It was open for debate if Pixar, Dreamworks, Blue Sky or any other animation studio understood how much of Mexico's national identity was tied into lucha libre. The Latin community kept the same skeptical eye when anything Mexican, and not just Dia de los Muertos was being appropriated for a film.

One of the main characters in Coco, Ernesto de la Cruz, was a celebrated musician and film star. Without reading a press release I could tell that he was based in part on the singer Pedro Infante (1917-1957). Infante had a velvety smooth voice and played a number of different characters on film. He was very charming by all accounts and insanely popular in his day. Most that grew up in Mexico were familiar with his films and even generations Mexican-Americans born in the USA had seen the films on television. Infante died in a plane crash at the height of his career. Like many stars that passed before their time it was a wound that never quite healed. Seeing a character design in Coco that reflected the man and the era of "Ranchera" films that he appeared in was something authentic. But the man, his music and films was only part of the story.

Most of the films Infante and his predecessor Jorge Negrete (1911-1953) appeared in were love stories. Often a love triangle between two suitors and a strong-willed woman. This was a tradition that the Book of Life understood and was able to recreate. The films often featured several popular songs. The highlight of each were the Couplas de retache. These were couplet duels, often between the suitors. The singers would trade witty jabs at each other. There were many well worded passages filled with double entendres. At some point one of the men would snap and the two would almost inevitably start throwing punches. When Negrete and Infante appeared on film some argued that there were triple entendres in the couplas. There was the literal meaning behind the words, the subtext to the lyrics and then there was the third meaning on how the personal and professional lives of the actors were always in competition. The two men were friends in real life but public opinion always saw them in competition. Did Unkrich and Pixar know these things about the classic films of Mexico before they started writing Coco? Or did they just want to use the ranchera film as "set dressing?"

Was Pixar aware of how some of couplas were not always between two men? One of the iconic duels was between Infante and Sofía Alvarez in the 1947 film Soy charro de Rancho Grande. The two were not love interests in the movie but they were trading some heavy verbal punches at each other. Alvarez appeared earlier with Infante in the 1946 film Bajo el sol de Jalisco. Whether competing against each other or singing in unison the female leads were often as important as the stars. It was not a one-sided affair, the women often had a chance to steal the movie. If music was important in Coco then the team at Pixar had to become aware how it had been presented in film. They needed to know who did the singing and why. What were they singing about and why the content and context was important? These were all things that Disney learned how to do before Pixar was ever formed.

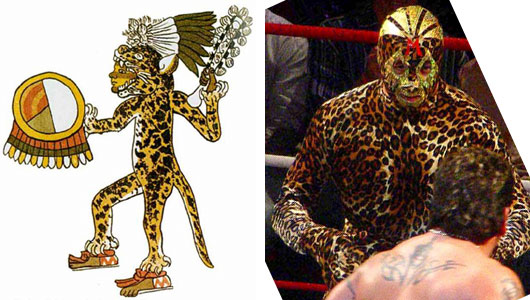

As part of a goodwill tour (on behalf of the US Government) Walt Disney and "El Groupo" traveled to South America. They learned about the customs, and traditions of the various countries. They visited with local artists as well as political officials and immersed themselves in the cultures of Chile, Peru, Argentina and Brazil. They released the film Saludos Amigos in 1942, which introduced the US to Pedro the airplane and the parrot Jose Carioca, the surrogate for Brazil. The following movie, The Three Caballeros (1944) featured new stories and introduced us to Pancho Pistolas, the representative of Mexico. The title song of The Three Caballeros was composed by Manuel Esperón. He was asked personally by Walt Disney to collaborate on the project. His hit song "Ay, Jalisco no te rajes" was the backbone of the theme. Jalisco and the capital city of Guadalajara, was the birthplace of Mariachi music. It was integral to the Mexican identity. The rhythms of Mexican natives, combined with the music from European immigrants (mainly waltzes and German polka) all helped color the mariachi style. Just like Dia de los Muertos and Lucha Libre, there were elements of the old world and the new world featured in mariachi music. These things helped make something brilliant.

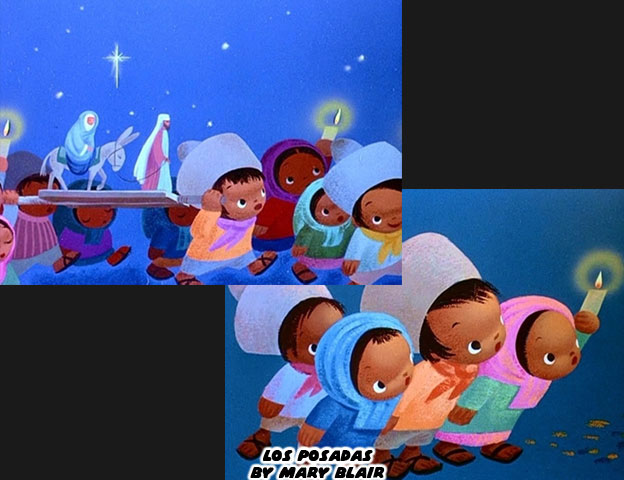

The senior artists that went on the trips were greatly influenced by what they saw. I would argue that nobody was more affected than Mary Blair. She was already a master of paint and color but her work forever changed during her travels. She was able to create several scenes that framed the frenetic energy of Brazil's nightlife and the more solemn Posadas of Mexico. The slight change in how she used color, the ability to capture the children of different ethnicities, would help her develop the figures on it's a small world many years later. There was no backlash when it was announced that the uniquely Spanish Catholic tradition of the Posadas would be featured in an animated project. Then again things were much different 74 years ago. News traveled slower, there was no internet and the voices of minorities in mainstream culture were almost nonexistent. Despite these things Walt's team created work that was respectful of the culture and could be celebrated universally. So this took us full circle. Now that Coco had been released we still needed to have the talk. My contention was not about whether or not Disney or Pixar could produce a good movie. My contention was about who was the telling the stories and why we couldn't tell our own.

In the golden age Walt Disney had his "Nine Old Men" the artists and directors he trusted to carry out his vision. The work they created set a standard that was hard to top. There wasn't much diversity then but that was a different era. They could still deliver a great film (or theme park) despite their lack of representation. That tradition carried on at Disney for decades. When John Musker and Ron Clements had an idea that would become Moana. Pixar boss John Lasseter pushed them to dig in deeper into the history of the Pacific Islands. By doing so they avoid making the story "Tiki" and instead a more authentic experience. Now there was The Pixar Brain Trust, the senior artists and directors that John Lasseter trusted to get things done. Again, there wasn't much diversity or representation in the lineup but there were results. Smash hit movies, beloved by all. It made me wonder why they didn't have women or minority directors. Why were a group of "white guys" the gatekeepers for animated projects, especially those about other cultures? Were they really the only ones that knew how? Or did they not realize that great storytellers came in every shade and gender?

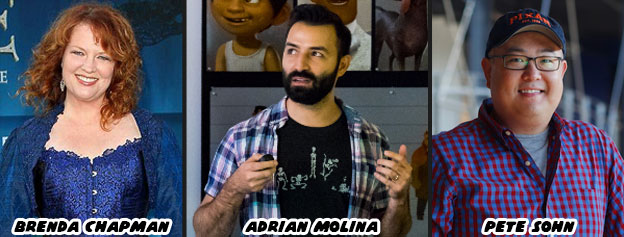

Brenda Chapman was let go from Brave, essentially her original mother/daughter story. When word got out that the Good Dinosaur was in trouble Pixar replaced the director with Pete Sohn, who did his best to lessen the blow or to be thrown under the bus, depending on how you saw the situation. For Coco they brought up long-time Pixar animator Adrian Molina to add an ethnic voice and co-direct with Unkrich. Neither Chapman, Sohn or Molina was considered part of the Brain Trust. If only I could figure out what the three were missing. Following the success of Coco it was doubtful that things would change. Instead both Disney and Pixar would find another culture to talk about, perhaps return to Africa or China. They would go out of their way to do research, bring in advisers and sign up some famous names. They would tout their authenticity during the D23 Expo and parade their stars. The people from that country would be happy that they were being validated by a big Hollywood picture. The world would keep on turning. Just once I wish the studios had a real conversation. With Lasseter on leave maybe now would be the time to acknowledge that a woman could do his job, a minority could do his job, and the Brain Trust could evolve. But I'm just a Mexican-American writing about Japanese fighting games on this blog. What do I know about representing other cultures?