If you were to ask gamers which science fiction universe they would love to live in they might respond with a variety of choices. Star Wars, Star Trek, Stargate, Battlestar Galactica, Mass Effect and Halo would probably be near the top of the list. Yet if you were to ask me which one was my favorite I wouldn't have to think hard about it. The UGSF continuity from Namco was by far the most interesting to me. It represented various stages in the fictional history of mankind.

From the first tentative steps into other solar systems to the first encounters against hostile alien lifeforms. The future of humanity was set in all of the beauty and chaos of the cosmos. There was sometimes a great struggle against monsters and creatures too horrible to imagine but also tremendous strides for human lifeforms across trillions of light years. As a kid that grew up admiring all of the sciences, but especially space science, this was a fascinating series to me.

Namco had been working through dozens of original titles over the past 30 years and tried to connect the dots on most of them. The UGSF series actually stretched out from the middle of this century (2040) all the way to the year 7650. Past that was unknown because Namco had yet to plan for it. To connect all of the dots that Namco had mapped out would include the history of civilization on Earth as well. The earliest adventures in Namco canon took place in ancient Babylon, some 3000+ years ago. The company had published adventures set at various points through the history of the world, including the feudal era in Japan, the dark ages in Europe and even the current era. In all the studio had over 10,000 years of canon that they could work from and jump to. It had taken Namco more than 30 years to amass a library of games that supported their obsession with canon. It was a feat that would have been impossible for any other studio to recreate. That was why I admired the company and their science fiction work more than any other studio.

Everything Namco created came from somewhere, it had a backbone and a heart. It was much more than a facade which was all that most modern game publishers could offer in their games. It was brilliant the way the company

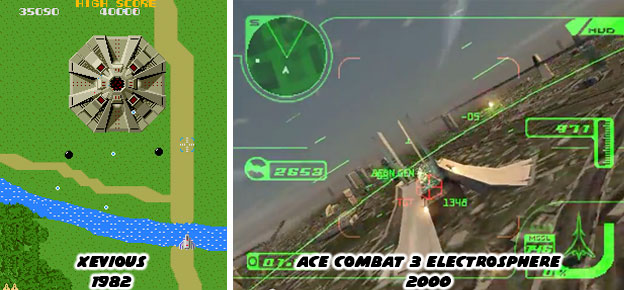

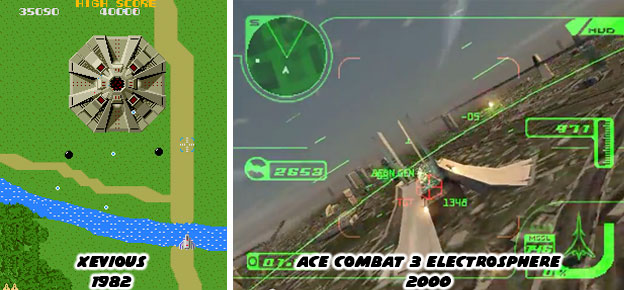

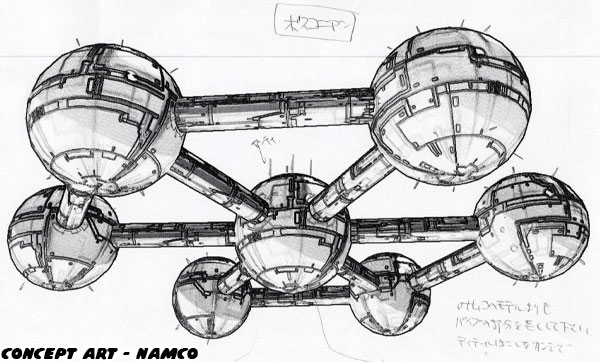

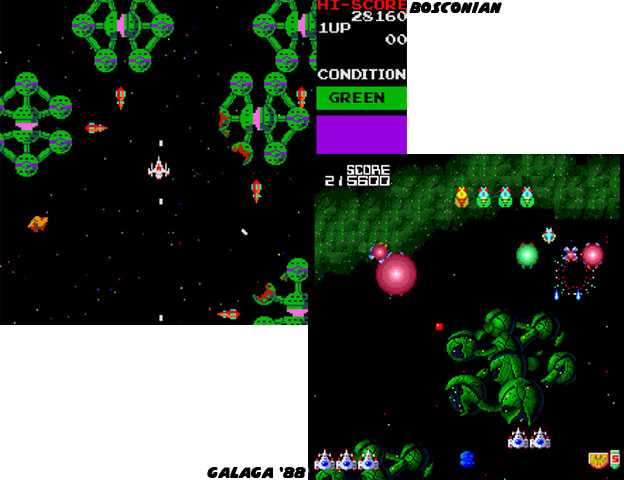

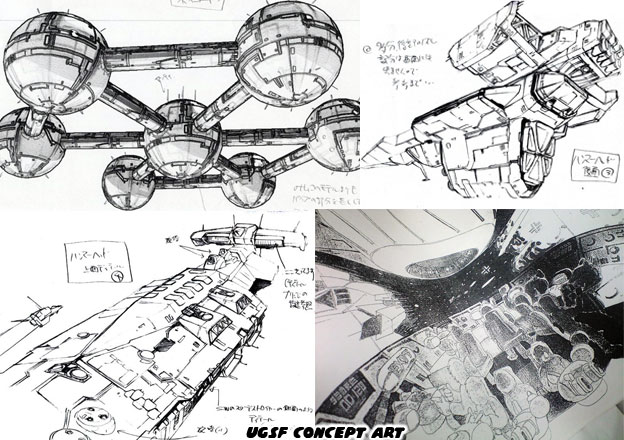

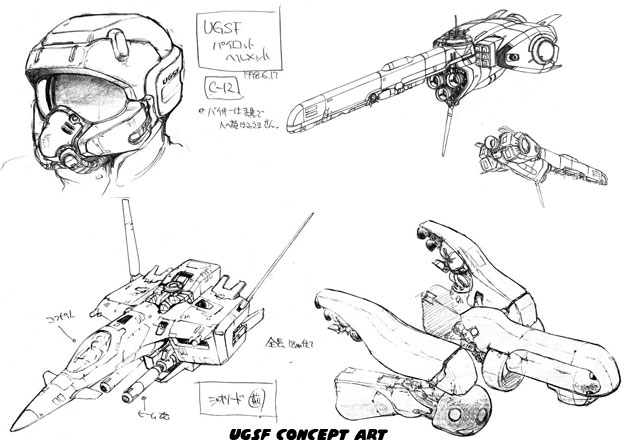

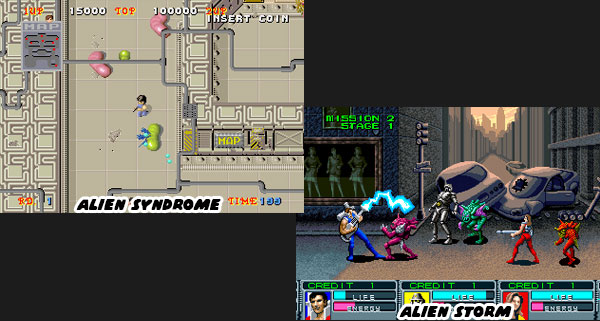

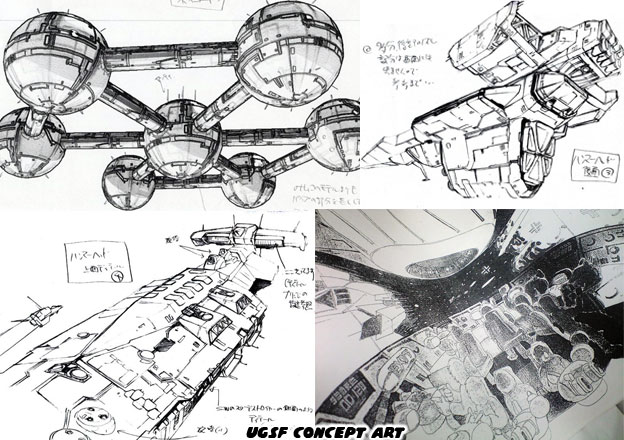

retconned the classic games like Dig Dug and Baraduke so that they fell in the same continuity as Galaxian and Galaga. The best part about the publisher was that they kept copious notes and arts on every UGSF title. In other science fiction titles there was a specific timeline that most games focused on. Perhaps there was a generation or two at stake like in Star Trek, or perhaps there was even a few centuries separating the adventures as in Star Wars. For the UGSF there were decades, centuries and even millennia that were points of interest for fans. The company actually knew how mankind managed to stretch from one end of the galaxy to the other. They knew every battle along the way, every technological achievement and every story worth telling. Those high points turned out to be the first generation of arcade, console and even mobile hits from the publisher.

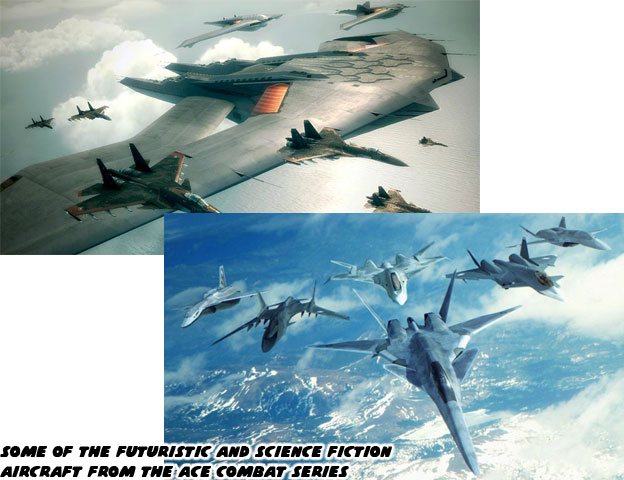

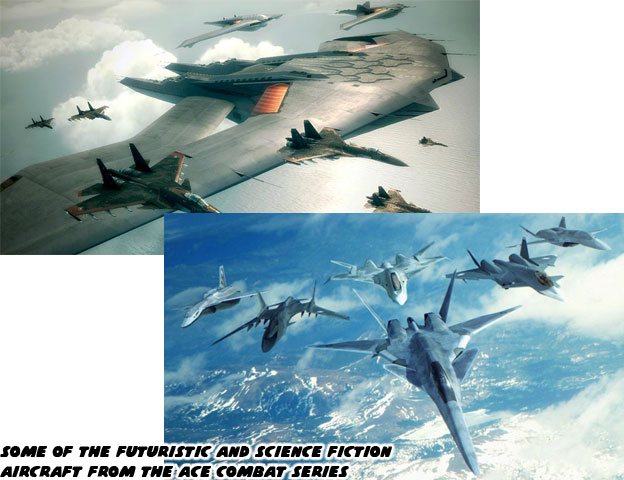

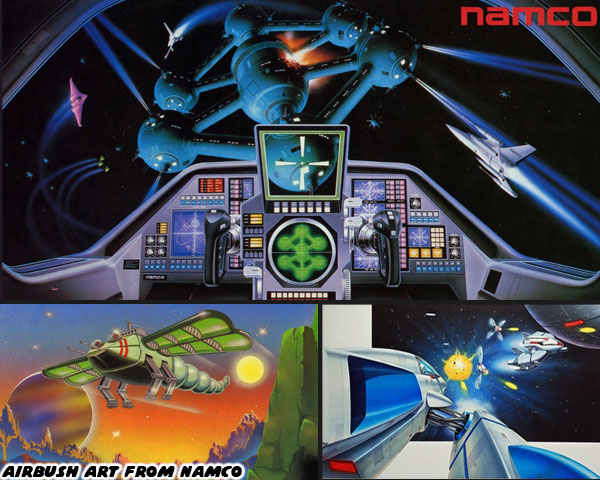

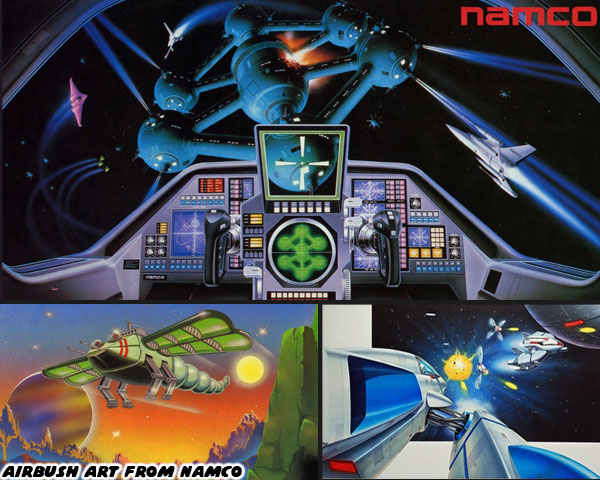

Growing up playing just about every arcade game that Namco published, especially those about space, had preserved that same sense of awe and wonder that I had as a kid. When I worked at JPL and was doing mission support over a few years, including the landing of the Curiosity rover, I felt as it all the quarters I had spent in my youth had finally paid off. From an artist and designer point of view I became enamored with the stylization of the ships from UGSF canon. They were not quite animé nor western sci-fi. The company had found a balance between the two that was awe inspiring. From the stealthy Coleoptera Fighter in Galaga to the massive Dragoon-J2 in Attack of Zolgear, there was a genuine sense of evolution for all of the fighter craft. It was something that not every team of designers could capture in other science fiction titles.

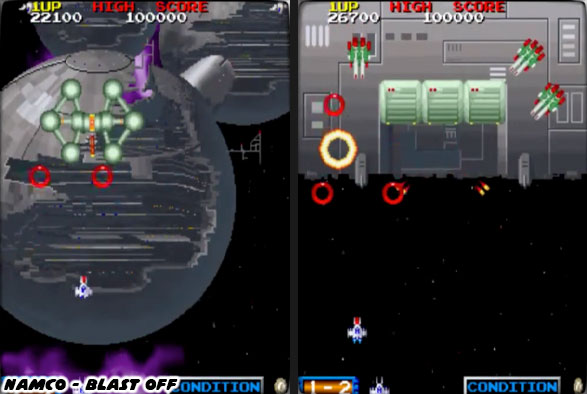

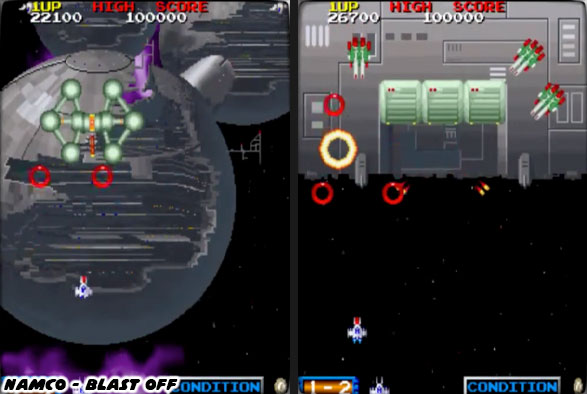

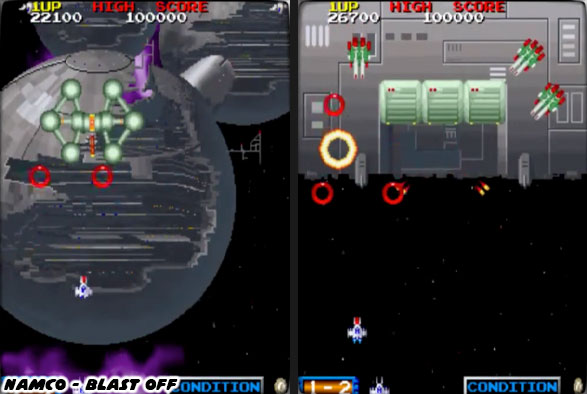

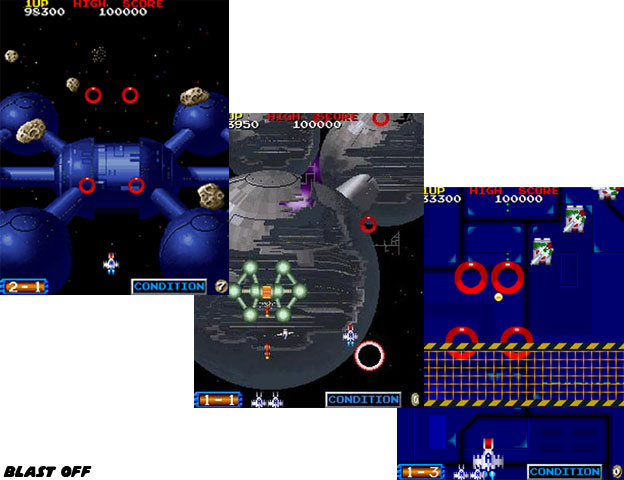

Of course every long-time fan of the UGSF series would ask where the overlap was. Several of the biggest titles happened within a few decades of each other, and some within galactic reach. Namco answered this question in the Kuusou Kagaku-developed

Star Ixiom. The title from 1999 was considered the pinnacle space shooter for the original Playstation. It became the benchmark from the publisher just as Ridge Racer Type 4 was for racers. The game blended the heroes and villains from a literal who's-who of UGSF canon, including Starblade, Galaxian, Nebulas Ray, Star Luster and Bosconian. The game was set in a first person perspective. Missions were spread all over the galaxy and what made the game innovative, aside from the free flying 3D dogfights, was the ability to "warp" from location to location. The stars would form a tunnel as players passed light speed and reached objective markers. It was the same classic effect of making the jump to light speed from Star Wars except now players could choose where they would visit with each jump.

The game could be held up to the standards set by Wing Commander and the Star Wars: Rogue Squadron series. The downside was that this game never saw the light of day in the USA. It was released in Japan and Europe only. Thankfully emulators helped die-hard fans in the states get a chance to experience it. It was a shame too, the game was beautifully done. It mixed the designs from each of the distinct universes well. It maintained the sense of scale and adventure from Starblade while allowing players to pick up missions on the home bases. The ability to progress through the missions at the leisure of the gamer was something that no Namco arcade game could ever allow. From a design standpoint every cameo made sense. Remember that some of the technology employed by early colonists, the Galaxians, were still in operation several generations later. Players would visit stations that looked obsolete in one sector of space and much more advanced in a different sector. The UGSF made do with the resources of every particular home world and defended it to the best of their abilities. It was a much more realistic approach to science fiction logistics than had been seen in other media.

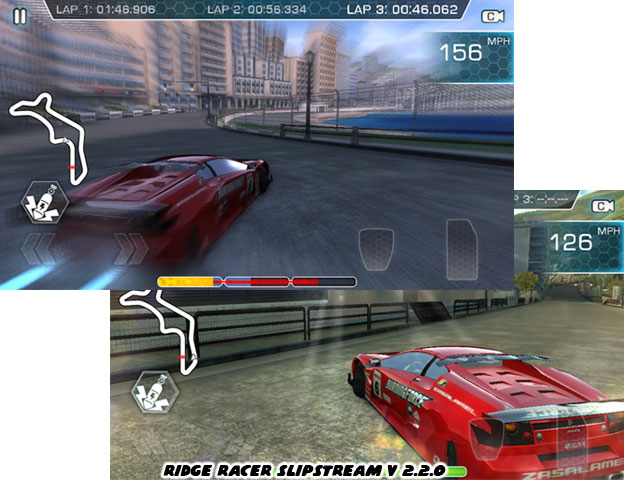

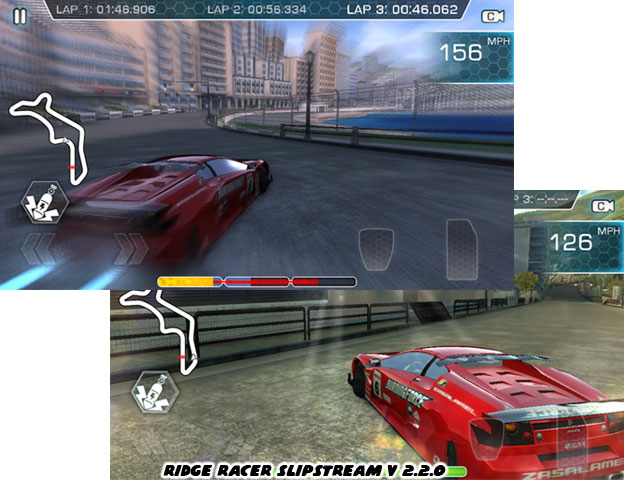

Star Ixiom was not the only gem that Namco kept from the west. Most of the decisions to keep a game in one region were business related of course. I often wish that the marketing people and bean counters did not have as much pull at the studio as they do now. Without taking a chance on new ideas the company would have stopped evolving after Galaxian and Pac-Man. Instead they decided to compete against the big boys in multiple genres. They took the battle to Sega and matched the juggernaut game-for game. Sometimes they had a better experience and sometimes they didn't. Unlike Sega however Namco did not seem to give up on their oldest franchises.

In 2007 the company decided to try their hand at a completely different format for the UGSF series. New Space Order was an

an arcade/PC real-time strategy (RTS) game. It was the first time the classic universe had been presented in such a format. It seemed to work very well too. Players chose from one of four different human factions as they tried to expand their respective empires throughout the stars. The ability to command entire fleets of classic and new ships from UGSF history was a real treat. Well designed space RTS games were extremely rare. The genre had been used in popular fantasy and science fiction ground combat titles like Warcraft and Starcraft. The format hadn't been seen very much in space shooters.

The game was actually set during some of the most formative years of the UGSF. In order to bring audiences into this world Namco produced

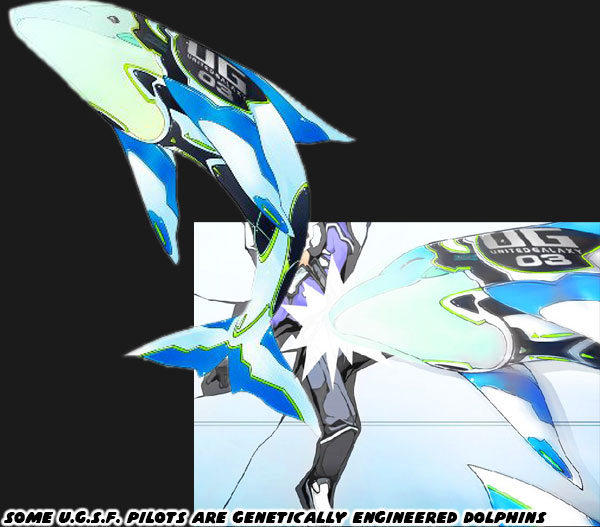

New Space Order - Link of Life - a web drama from 2007. The series explained how far humanity had come and how factions had grown out of planetary ties. It told the story through the eyes of a select group of young pilots, engineers and officers. Each held a distinct view of their world and told the story of how their nation and planet had to fight in order to keep their history and culture alive. What was great about the series was how much in depth they went into the actual canon established by the game series. Many of the notes and designs that the company had been sitting on were finally brought out.

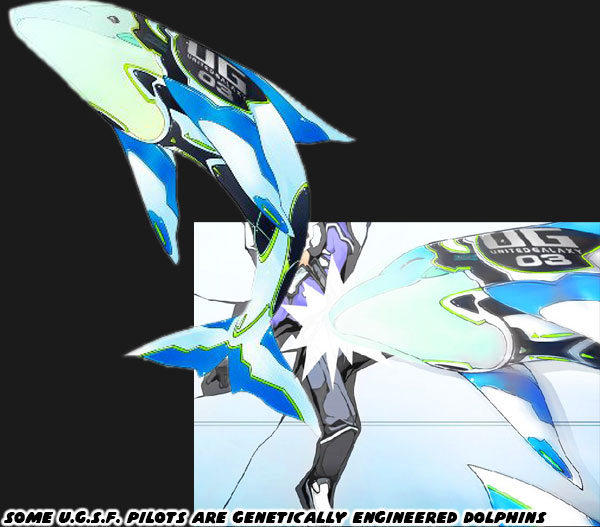

The web series and game managed to touch on many of the high points of UGSF canon. They brought out the relationships between the classic arcade and consoles hits and gave them entirely new dimensions. They explained the origins and outcomes of the wars against ETI (extra terrestrial intelligence) from Galaga, Bosconian and Battsura. They highlighted how humanity had developed ships that were designed to combat the most highly evolved of alien species, such as the robotic UIMS. Many of these ships were several kilometers in size with the largest mobile platforms being as big as an asteroid. The smaller ships turned out to be very useful in combat because they could bypass the defenses of the more massive targets. Players actually got a chance to set up both offensive and defensive capabilities for their particular factions. They would have to figure out which ships worked best for certain missions and how they would have to adapt to constantly changing threats. Namco dubbed this form of gameplay "Fleet Assault Tactics."

The game was absolutely gorgeous. It had twinkling stars and spiraling galaxies billions of light years in the distance. Players learned to terraform and connect their planets and navigate around asteroid clusters while defending their home worlds.

With a much more laid back classical soundtrack to help the player feel more like a military strategist than a space cowboy. The title was taken offline in 2009 much to the disappointment of the fans. I can understand that it was a business decision. Arcade games were a hard sell in the US and western audiences favored action over RTS titles by a wide margin.

Of course I would hope that someday soon the company would return to their galactic roots. New Space Order and the other experiences from UGSF canon certainly deserved more chances. Even without a new science fiction title in the works the influence of the space legacy was hard to ignore. The UGSF canon had become ingrained in the culture of Namco. It would pop up in some of the least suspected titles. When it did it gave long-time gamers a chance to reflect and long for the future.

If you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!