It was not very hard to separate the designers working at Namco from what they had produced. The games released by the company had a certain aesthetic style associated with them, a Namco “fingerprint” if you will. Gamers sometimes confused the word graphics for aesthetics when they talked about the look of a game. To be clear it was the stylization of the characters, vehicles and environments that made up the aesthetic of the title. It had nothing to do with whether the game was sprite or polygon-based. Some developers earned a following for how aesthetically pleasing their games were. Titles like Katamari Damacy and Jet Set Radio had unmistakable aesthetics.

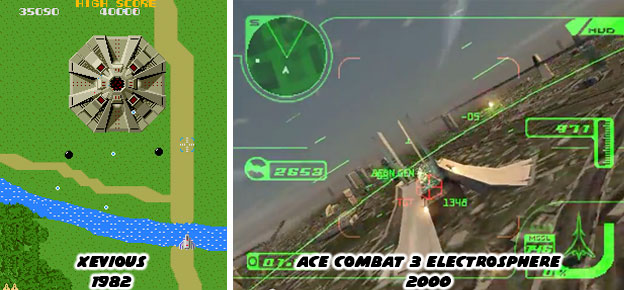

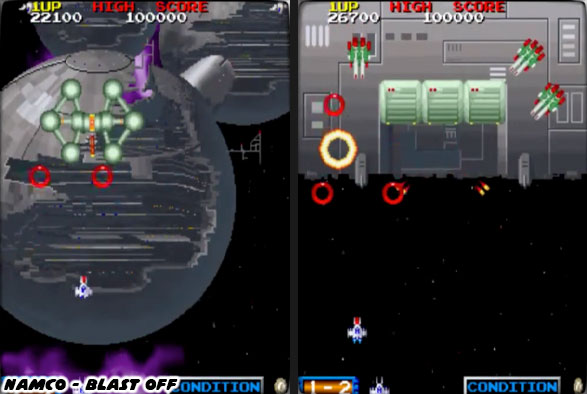

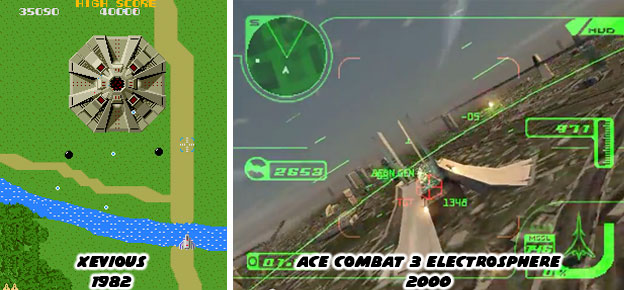

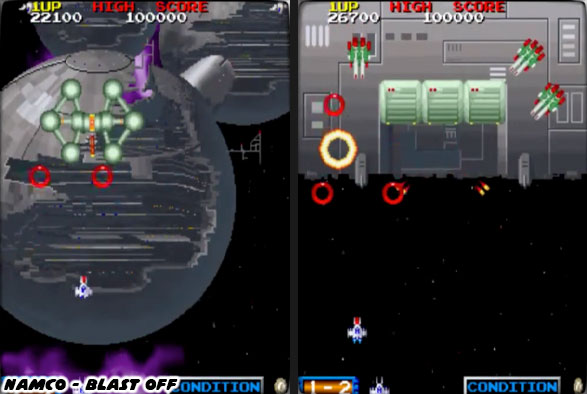

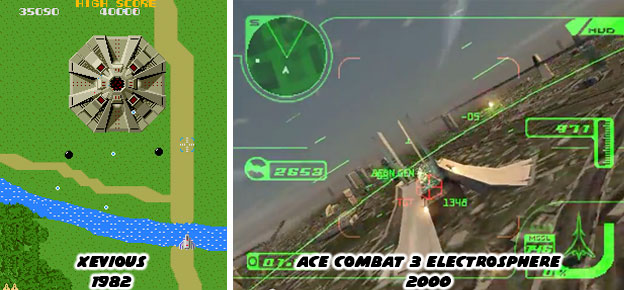

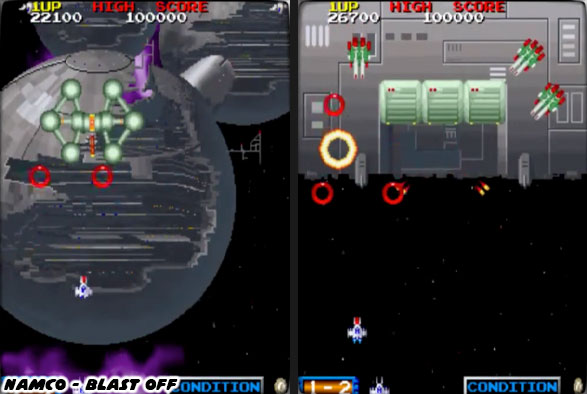

Seasoned players could tell which development team had worked on a particular title just by looking at the game. Through the history of Namco the development teams had used a certain aesthetic to connect the various franchises. In some examples they were obvious, like the Bosconian ships that appeared in Galaga ’88 and Blast Off. In other cases they were very subtle and could have been easily overlooked. The details in the background, the terrain and architecture of certain games had some crossover and this was sometimes missed by players. The longest running string of hits from the company had been rooted in UGSF continuity. The developers working on other games were proud of their contribution and wanted to make sure that the series lived on in one way or another. It was especially important to them once the era of the arcade shooter had died off. The angular buildings and factories used in Ace Combat 3: Electrosphere were reminiscent of the Andor Genesis, the alien mothership featured in Xevious. This was no coincidence. The developers were very slowly shaping the world to fit into the storyline of future releases.

The first game that the developers looked at made the most sense canonically. The Ace Combat series featured military aircraft fighting for supremacy over fictionalized nations. The game always had a forward-thinking tilt to it. Like Tekken and Ridge Racer the game was set a few years in the future and had all the supporting details to reinforce that idea. Whether it was the aircraft, the weapon technology or even the details in the city, everything about the games screamed progress. For audiences it was just a fun dogfighting simulator with dozens of different aircraft types and plenty of memorable missions to keep them engaged. Ace Combat actually made great use of a gameplay technique that the development team had learned from Ridge Racer.

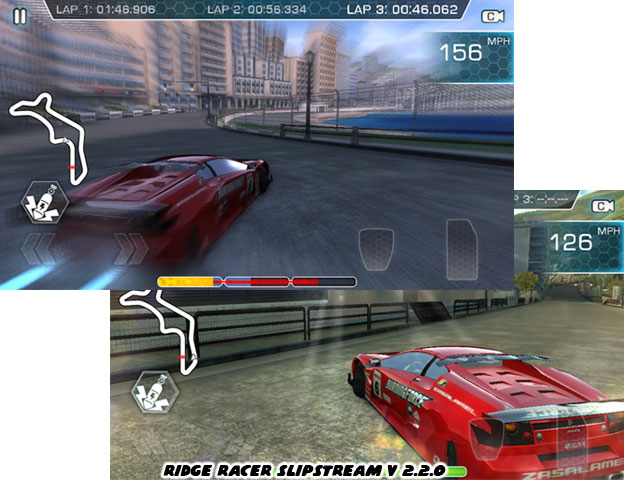

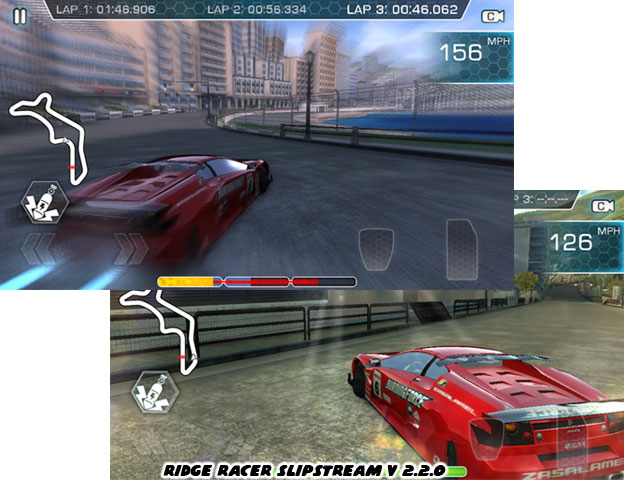

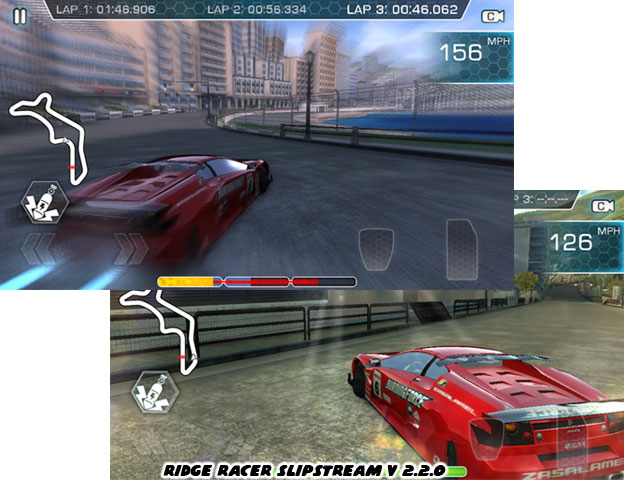

Players had to earn their aircraft by completing scenarios. Finishing levels in a timely manner and also side objectives meant that players could earn better aircraft than those that simply finished the main missions. In a similar way the players of Ridge Racer earned superior cars by beating track times and challenges. Simply completing a race was not enough to earn the best cars in the game. This forced serious players to learn the nuances of each car and track. Players learned how to draft and block, how to find a line through a crowd and when to use the nitro boost. As players improved they were able to upgrade their existing cars and earn better rides.

In Ace Combat players had to learn the complexities of dog fighting in a rather short timeframe. The lessons and complex math equations that they would have been taught in training school would never have worked in a high-paced game setting. So every mission became on the job training. How to lead a target, how to fly defensively and even how to line up targets ahead of time were the nuances that players had to learn. Players that mastered the intricacies of fighting were rewarded with the best possible aircraft in the game. Ridge Racer by comparison had made it easier for players to unlock the best cars in the game. They did not necessarily have to be the best drivers on the track, but rather be the best at drifting and using nitro boosts. In real life and in more realistic racing games, a well-executed drift required finesse and solid driving skills.

In Ridge Racer a drift recharged the nitrous tanks. So a player that became good at drifting could keep boosting and pass up opponents more easily. The game engine even adjusted the direction of the car as it slid to compensate for the lack of driving skills from a player. This sort of hands-free driving was most apparent when the car was moving very quickly. In every turn all the player had to do was initiate a drift. The game would take over and pull the car around the corner at the perfect angle. The player did not have to do any sort of steering so long as they were going very quickly. Only at lower speeds were they expected to steer the car. This was not always the case, early Ridge Racer games were demanding on the drivers. Rage Racer forced players to become better drivers and react faster and faster with every class upgrade. There was no sort of automatic steering to help guide players around turns.

Ace Combat by comparison did not try to dumb down the combat experience. In order to achieve the best possible aircraft the player would have to become a better fighter. Objectives were spaced out early on in the game and combat was limited so that audiences could learn the controls. Little by little the difficulty would increase. More targets would be added and more opponents would join in the battle. By the end of the game the player would find themselves reacting at lightning speed and taking on dozens of opponents. Namco and their developers used this learning curve to their advantage so they could create some of the most amazing combat portions in modern gaming. The gut-wrenching

Trinity Missile Strike on the White House at the end of Ace Combat Assault Horizon was a perfect example of that. On the other hand Ridge Racer did not introduce new tracks that took advantage of the fastest cars in the game, making the final races in the title feel anti-climactic.

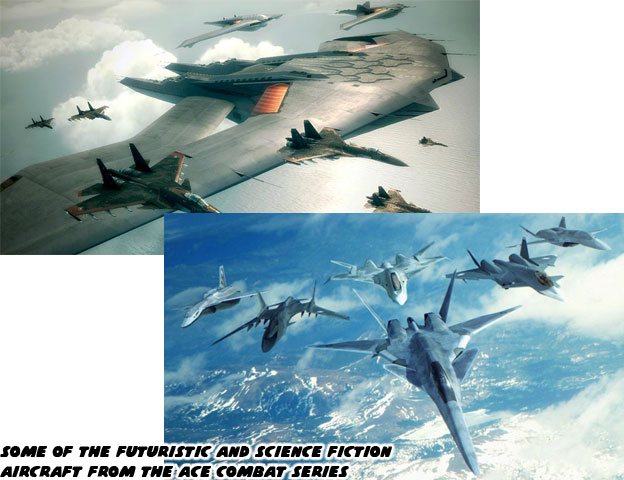

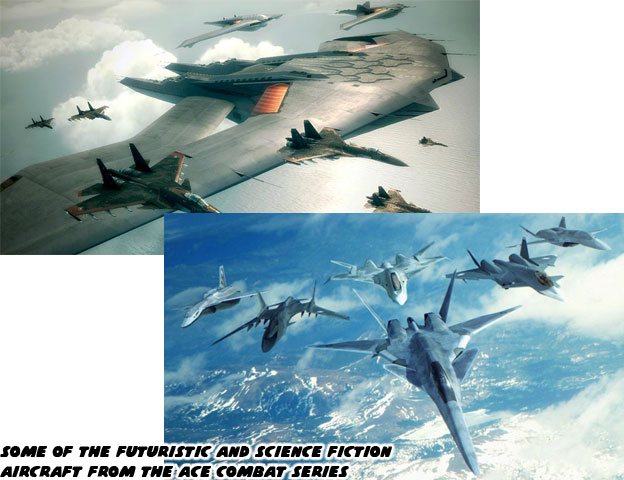

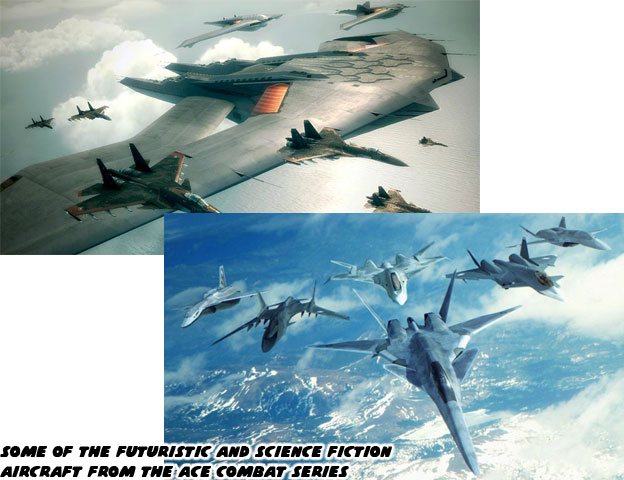

What could never be debated was how amazing the vehicle designs were in either game. I had already highlighted how the cars in Ridge Racer took the best elements in production and concept cars and put them on the track. For the Ace Combat series the developers took cues from the best fighter jets and prototypes and put them all in the sky. Some of the most radical ideas in aviation would become the backbone of the series. From the stealthiest fighter to the most gigantic

airborne command cruisers had a place in the Ace Combat universe. The diversity of designs and jet types called out to every spectrum of fan, just as the cars big and small had done for Ridge Racer.

There was an unmistakable science fiction element to the Ace Combat series. It wasn’t enough that the planes were futuristic. They had to fit the vision of aircraft a few generations down the line. The way their aeronautics looked and worked had to be believable. The way weapons were stored and fired, the ability to deflect missiles and defend themselves from enemy fire had to be plausible as well. The people at Namco had to cover all of the angles from a design standpoint and still create a story that was immersive that would help bring players into the experience.

Ridge Racer had the fortune of being a racing game and allowed a player to assume the role of a faceless character. The drivers did not necessarily need to be spoken to by a crew chief or even a teammate but when those details were available, as in Ridge Racer Type 4 and R: Racing Evolution then it was appreciated. For the most part the cars chosen by the player spoke for themselves. Ace Combat had a similar gameplay element going for it. Players were faceless pilots and the planes they selected did all the talking for them. The supporting characters, the wingmen and rivals all spoke to the player and didn’t expect a response, this type of writing helped maintain the illusion. The Ace Combat series would actually become a nexus that bridged the canon of Namco’s past to the future. The next blog will highlight these connections. As always if you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment