Bugbear Entertainment had a very specific vision for Ridge Racer Unbounded. They created a game with a certain tone and atmosphere. It was much darker than fans of the series were used to seeing. In order to get audiences to accept why the racers were willing to destroy their own city they had to give them a reason to. The city of Shatterbay had a very strong contrast between the political and business elite. Those that ran the city did so from the comfort of glass and steel skyscrapers. Everything away from the heart of downtown, pretty much the rest of the city was a slum. The actual working masses lived in poorly maintained, poorly run boroughs. The city looked worn and beat down from years of neglect. Buildings were all in muted colors, it had obviously been years since they had seen a fresh coat of paint. Trash and graffiti littered the streets and roads were in sorry condition. It didn't take much for the "Unbounded" to take the system apart one wall at a time.

The game was very much calling out to the frustration that the Occupy movement had been trying express. The inequity was what the 99% felt towards a system that was rigged against them. Social commentary had been very lightly sprinkled over video games for the past four decades. As storage, graphics and animation increased so could the ability to tell more complex stories. Strong political statements began to creep in over the past few console generations. Since some racing games were taking on the qualities of action titles then it was only a matter of time before some of the political themes would get carried over as well.

Unbounded was an extremely rare example of that type of game design and storytelling. The ability to race and destroy had always had a cathartic effect on gamers. It was not only crucial for the Unbounded story but actually made for a fun experience. Since the game did not actually have pedestrians to run over or carnage, as in Carmageddon, then the destruction was more acceptable for younger audiences. Sometimes it was okay to cut loose and just smash into things in a racing game. The release was similar to what violent fighting games did to get aggression out of fans.

Namco knew a thing about fighting games as well. They were well versed in creating worlds where heroes and villains were in constant battle. Their worlds were believable but presented much differently than those from the west. Bayshore, the location for several Tekken games, was as big if not bigger than Shatterbay. Yet there was a stark contrast between the way that metropolis was presented. The Japanese designers wanted to show a realistic world that also had a hint of futurism rather than nihilism. The logistical problems of a major city such as traffic, roads, and mass transit were always in the minds of the developers. These things were always present in the Tekken games. The cities were always alive and breathing, with traffic flowing back and forth and monorails carrying passengers to work. Even if these details could only be seen from a distance they were nonetheless there. Bayshore never looked old and neglected as did Shatterbay. The masses did live in gigantic apartment buildings and condos, but those buildings were as spotless as the skyscrapers that the powerful ruled from. There was no graffiti, no litter and nothing that would give audiences an unfavorable impression of the location.

Namco was not ignorant to the trends of the world. The studio knew that they could not present a completely utopian view of the civilization, especially within the Tekken series. War and strife were still very much relevant in canon, however that reality did not trickle down to the masses. The citizens of Bayshore and other Namco cities did not live in constant fear, nor were they protesting the establishment. The Mishima Zaibatsu and the G Corporation had done an impeccable job convincing the masses that they were working for the public good. They showed this by creating enormous public works projects, hosting the King of the Iron Fist tournaments and running cities which were seemingly free of any crime.

Of course the public works projects were usually building enormous underground bunkers for military units or research facilities for mad scientists. The Iron Fist tournament was a cover for paramilitary soldiers to try and out each other in front of the sponsors. Criminals were rounded up by the zero tolerance private police force or recruited by the Zaibatsu and other organizations. There was much more happening behind the scenes than gamers or even reviewers had realized. Namco created cities that would shine like a beacon to the rest of the world and at the same time hide a dark secret. By comparison Bugbear Entertainment thought that western audiences would not "get" that Shatterbay was corrupt unless it looked like an enormous slum.

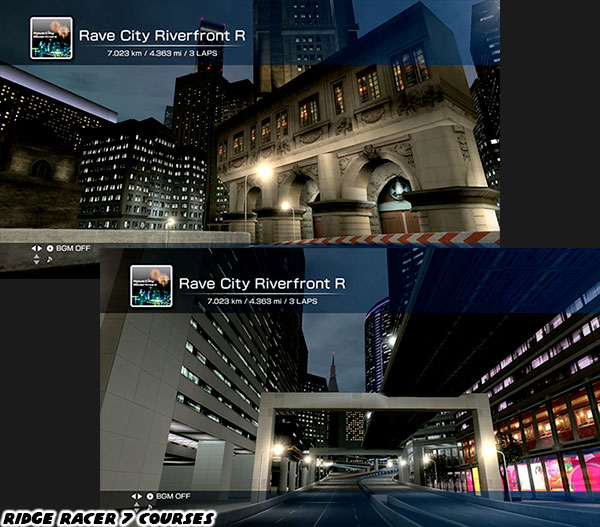

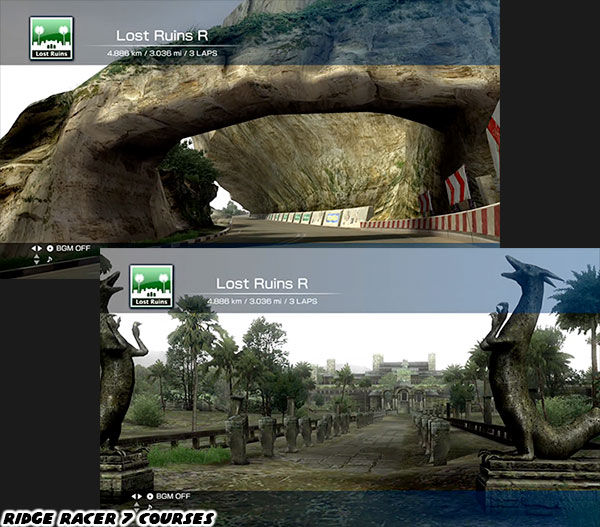

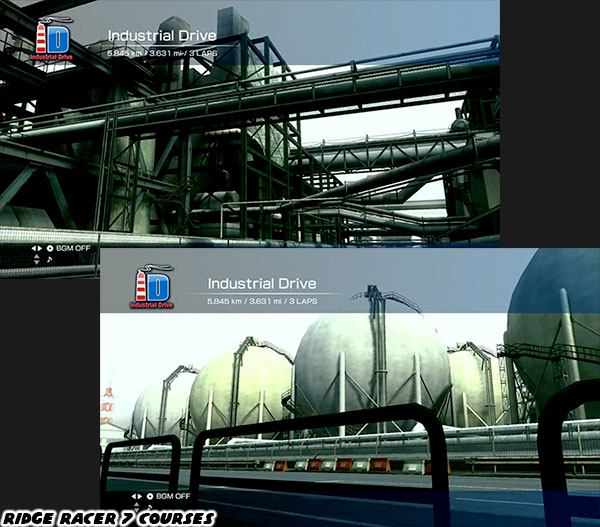

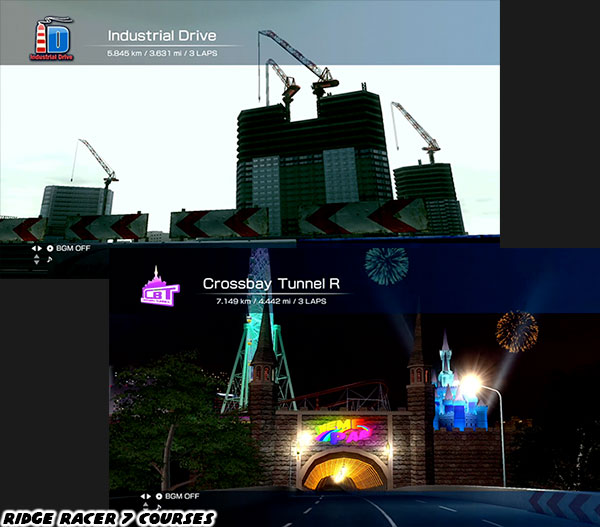

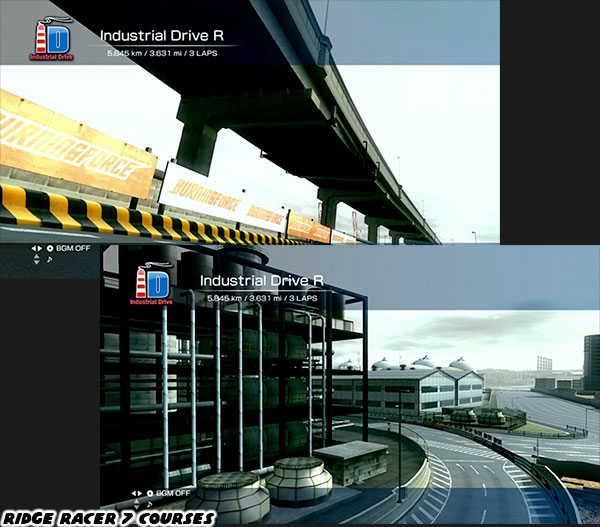

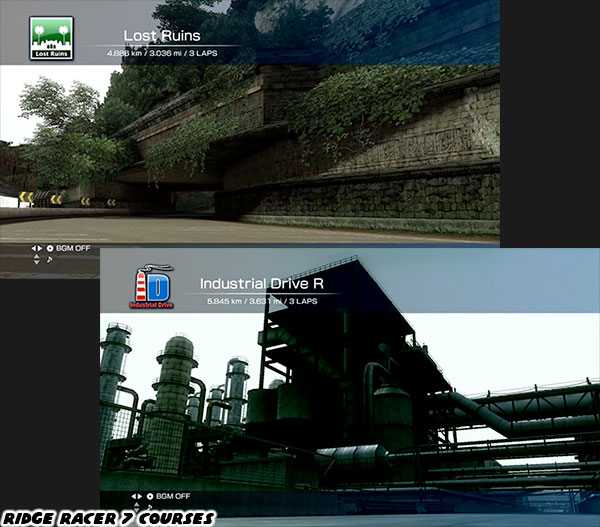

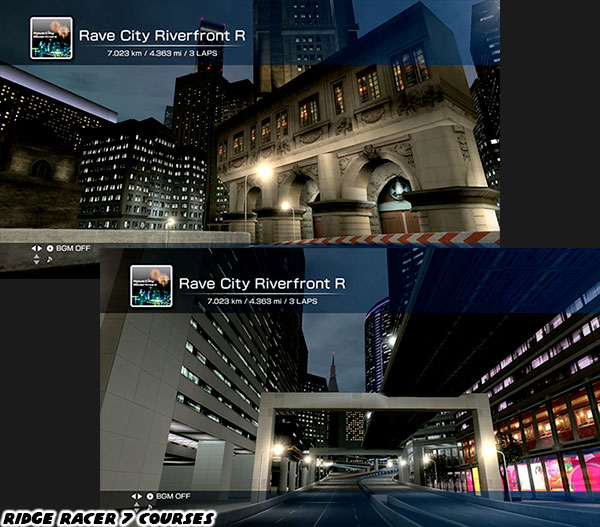

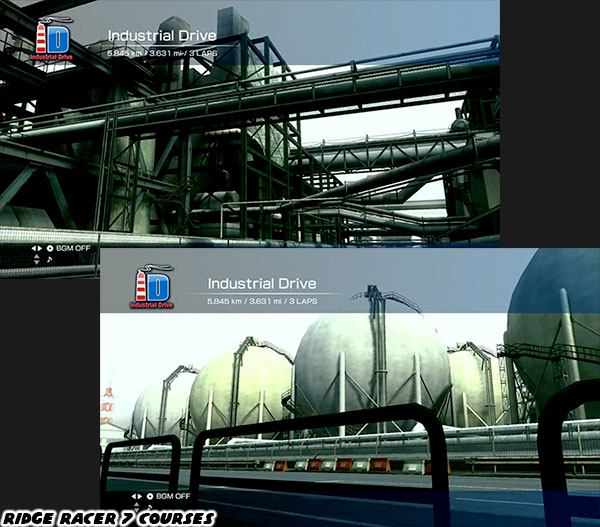

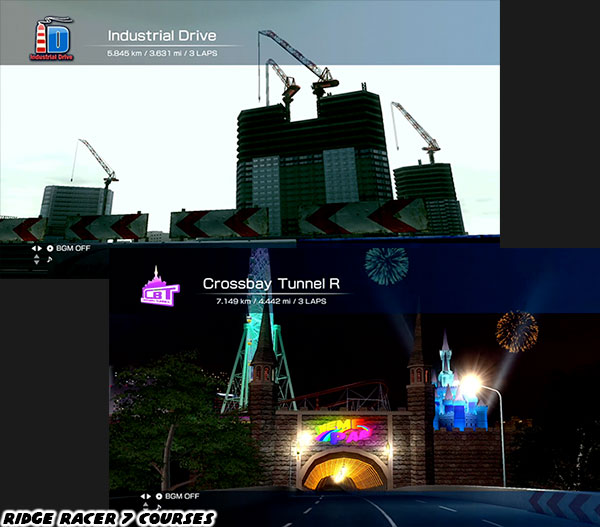

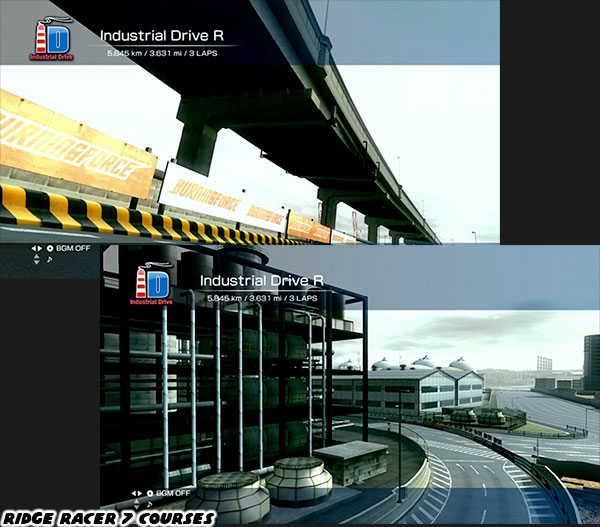

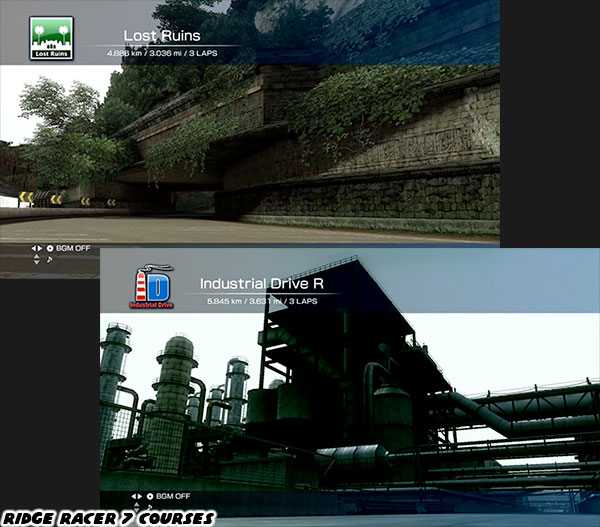

Namco designers knew that the levels featured in their franchise titles had to look believable. Bayshore and Ridge City needed to have bustling ports, refineries, airports and freeways. These cities could not simply exist for the sake of fighting or racing tournaments. Although to be fair they were certainly laid out to cater to them. Namco had demonstrated that levels could have a tremendous amount of atmosphere without it being all dark and gloomy. Dusk could look amazing instead of ominous in an industrial area. Even an overcast day in downtown could look like paradise because of how the city was framed. Ridge City was even more utopian than Bayshore in this regard. It was hard to get an unfavorable take on the city because Namco was willing to let audiences enjoy the atmosphere.

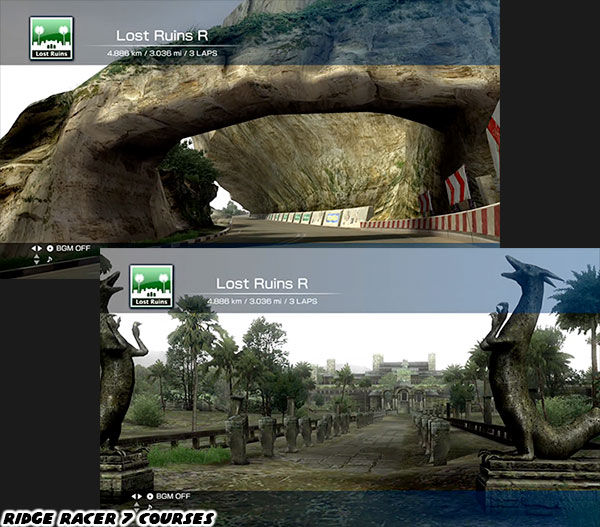

There were layers and layers of details that went into the creation of each stage in the previous Ridge Racer games. Unbounded seemed hollow by comparison. The manicured lawns, enormous fountain, European clock tower and craftsman-style mansions that lined the Old Central course. The neon splendor of the Crossbay Tunnel which ran under Rave City River. The span bridge that crossed Ridge Bay and had been a staple since the very first game. It was better known as the Harbor Line 765 circuit. It had been featured in many sequels and became symbolic for the series. Yet there was a small town in the shadows of that bridge. It was the original settlement that Ridge City had grown out of. The remains of a Spanish fort and an old pueblo had remained untouched for several centuries. The humble origins of the greatest Namco metropolis made up the Island Circle level. The juxtaposition of the old and the new was something very subtle. It was something that gamers might have overlooked. It was something that the gaming media may have even ignored. Yet it was also something that not every studio was capable of doing.

Bugbear had not paid close attention to the classic Namco levels. They missed the nuances that made up many memorable stages. Several of the locations featured in the series were as iconic as the race cars in the game. I would go as far as to say that they were as memorable as the fighters in the Tekken series. A great race course, both the real and fictional kind, could have a personality after all. The scenery that surrounded the locations, the personalities in attendance and sponsors that were cutting deals from private suites high above the courses. Every track told a story. Every city host had a history and roots as rich as Ridge City. Some of the best could be considered

almost SEGA good in fact.

The best tracks in Ridge Racer had a timeless quality to them. Whether they were set in a bustling metropolis or in a jungle outcropping they did not instantly date themselves. By using a backdrop that looked a lot like current New York City Ridge Racer Unbounded locked itself into one era. In a few years the railcars would look even more dated than they already were. The muscle cars and exotics would be further our of place and the architecture, even for downtown, become antiquated. The dilapidated city of Shatterbay would no longer remain worth revisiting. Ridge City on the other hand would always be a welcome sight to fans of the franchise.

Bugbear did offer racers something that very few titles could. Ridge Racer Unbounded allowed them to create their own race courses and share them online with the community. Players earned the pieces for the basic and advanced editors by completing races and earning achievements. In the basic mode players could lay out a course by rotating and dropping curves and straightaways over a blank borough. Some sections of each track piece were designed with objects and obstacles that could be destroyed by the race cars. In the advanced mode players could add in additional details to each course including ramps, parked cars, walls and loops. These details could even be stacked and placed mid-air for the most creative editors.

The editor was not as easy to use as gamers had expected. In the PC release of the game it was broken from the onset. Players had to wait for Bugbear to release a patch to solve many problems with the editor. There was a surplus of courses online for players to try and review. It was as if for every one player a dozen variations was waiting for them. The drawbacks to Ridge Racer Unbounded, the lack of originality, began to show thanks to the editors. The same assets that the Bugbear had used to create the game were available to players. This was not bad in and of itself, however while racing through the game it was apparent that the developers had released a title that consisted of mostly edited set pieces. When those levels were combined with bland cars the experience felt cheap. It was not the Ridge Racer that I was a fan of.

Sandbox editors were nothing new to the genre. Trackmania by Nadeo lived up to its name. As one of the longest running PC titles with an editing program it had earned its name by allowing level authors to go completely crazy. Gamers could create courses that were as technically challenging as real Formula-1 stages, or they could create outlandish courses that would have been the envy of a Hot Wheels stunt track. The best part for audiences was that they didn't even have to be any good at driving to enjoy the racing experience. Some editors created tracks that were a series of twists, loops and free falls that would have been impossible to navigate. All the players had to do on these courses was

Just Press Forward, or rather hold down the accelerator. The track would guide the car from beginning to end and allow gamers to enjoy the sights of the course. It was a lot like creating a dizzying ride in Roller Coaster Tycoon.

The editor in Ridge Racer Unbounded was not in the same league as Trackmania. Even with dozens and dozens of potential pieces to unlock and thousands of level combinations that they could come up with it was a drop in the bucket compared to what a more robust editor like Trackmania offered. The stages in Unbounded lacked the charm of the classic Ridge Racer tracks as well. The earlier Ridge Racer courses told a story. It was a story that would remain more promising than the future of Shatterbay. Namco tried to extend the life of the game by announcing Ridge Racer Driftopia in 2013. Essentially it was a free-to-play MMO racing game using the Unbounded engine. The spectacle of the action racing games was not enough to keep players engaged. It happened to Burnout and Need for Speed and would happen to Unbounded. Ridge Racer was a series that worked best when audiences lost themselves in the world that Namco had created. The next blog will take a closer look at what Namco lost when they went with the vision laid out by Bugbear Entertainment.

If you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

The potential for new courses always seems exciting, but have a broke track editor... well hindsight is always 20/20

ReplyDelete