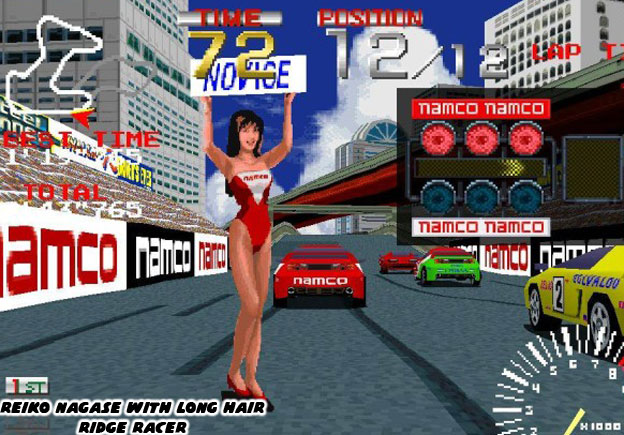

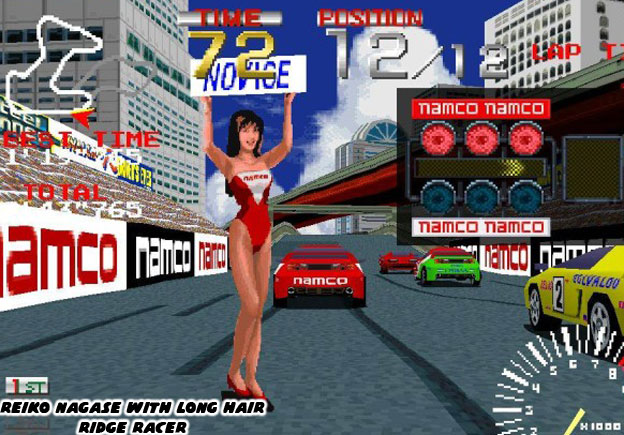

Arcade fans noticed the leggy grid girl Reiko Nagase in the original Ridge Racer. She was the only sprite-based character in the otherwise all-polygon graphics engine. Reiko was designed as "cheesecake" for the male audiences. She wasn't the first character designed for that purpose but most certainly became the longest-lived. In fact when she was put into the game she didn't have a name. By no stretch of the imagination did Namco make up her role. In many professional racing circuits models wearing team livery were used to pose next to the race cars and motorcycles and sometimes accompany drivers to the pit. The term

paddock girl became synonymous with the skimpy costumed models.

In Japan they were referred to as race queens and dressed sightly more modestly. They often wore pantyhose and one-piece swimsuits in order to minimize the skin show. Reiko had long hair originally and was presented with more class than the typical paddock girls. There was something interesting however about her and her fellow race queens when compared to the women that had appeared as eye candy in early titles.

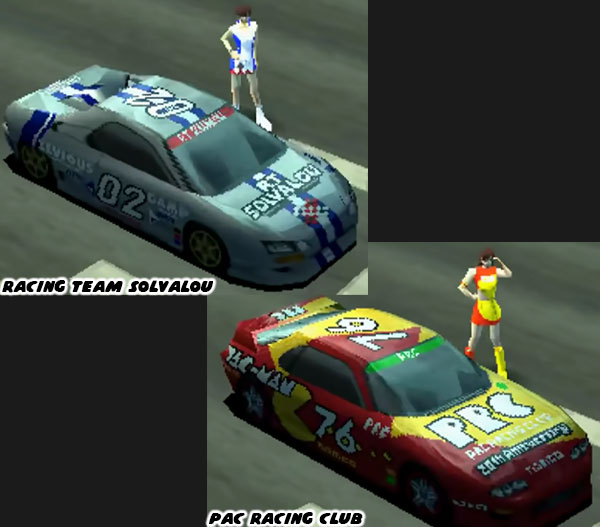

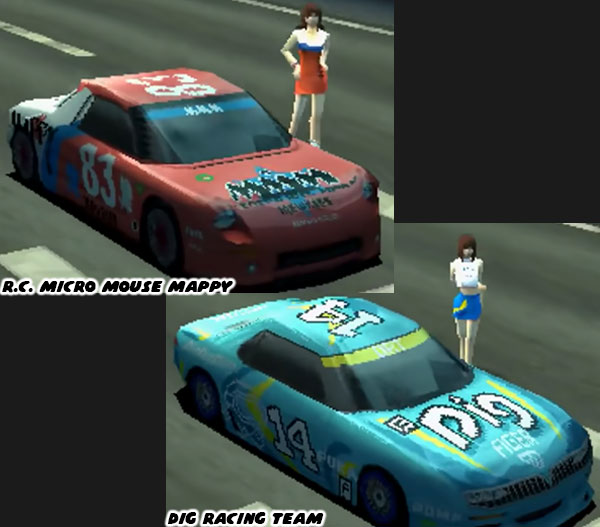

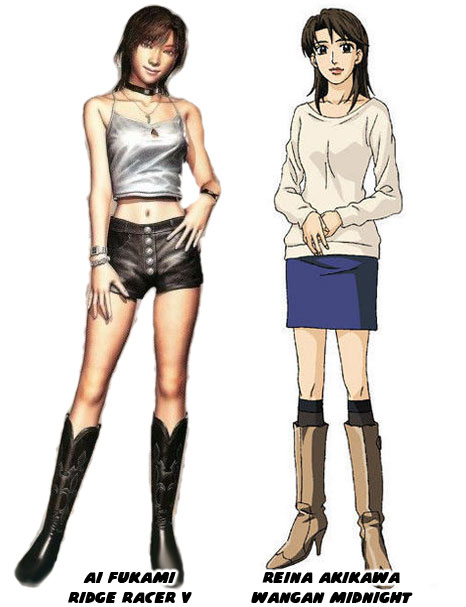

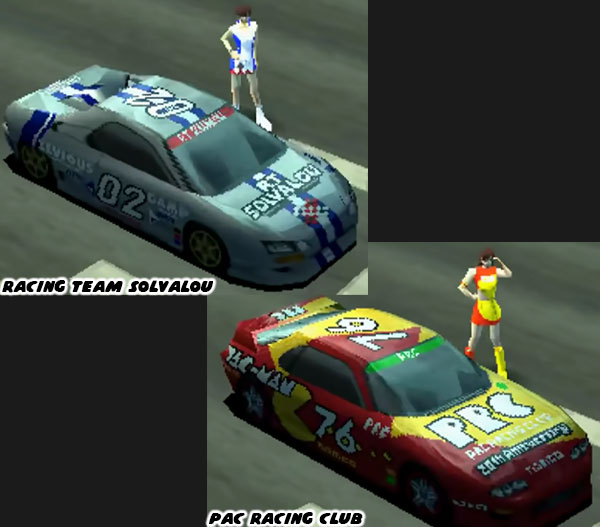

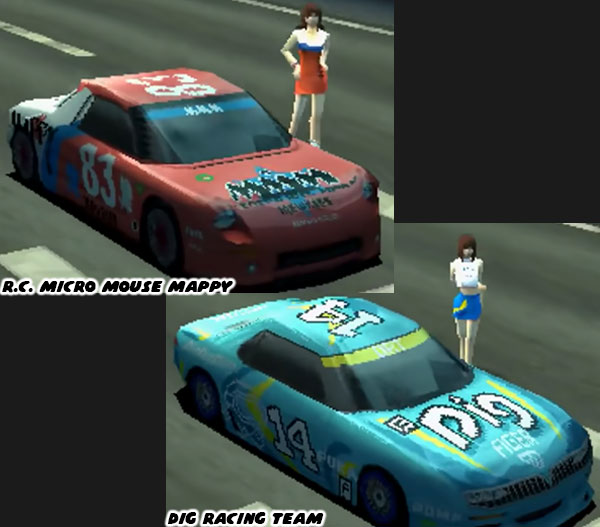

The race queens in Ridge Racer would keep the long hair and bright costumes for several more appearances. Namco had retconned the other grid girls holding up the title cards as Ai Fukami and Hitomi Yoshino. The developers saw potential in having a race queen become a mascot for the series but it would take a radical internal shift to pursue that idea. When Namco lost the original Ridge Racer team to Sega they began trying to reframe the game and save what they hoped would become a franchise that would rival the earlier Pole Position smash hit. Ridge Racer 2 from 1994 was very much a "safe" sequel from the new developers. It improved the framerate, physics, tracks and car selection but was otherwise a plain experience. It was the subsequent game that really began to push a new direction and establish the elements that would indeed turn it into a franchise.

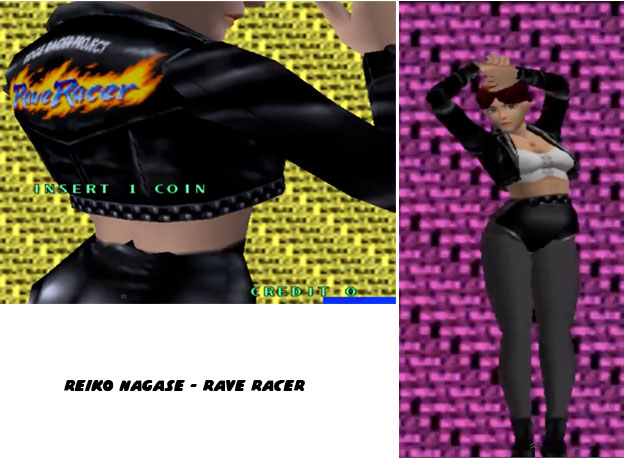

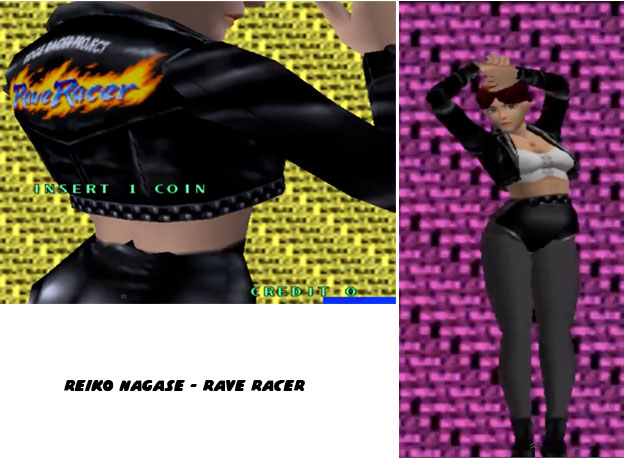

In 1995 arcade visitors had no idea what type of dramatic shift that Namco had planned. The third game was an experiment. Dubbed a Ridge Racer Project the re-titled Rave Racer had a frenetic soundtrack and wild graphics that made the game play more like a music video and less like a simulator. Even the attract screen was directed like a music video. In the '80s arcade games would just go through a loop of gameplay footage and feature a title screen. As technology improved so did the ability to present graphics and audio with greater fidelity and more channels of sound and color. Developers would sometimes create original music and animations that would play on loop when no one was on the game. These features were designed solely for the sake of attracting players to the cabinet. They did not have to rely on actual game footage to sell the experience. Hence they earned the name Attract Screens. Rave Racer had a short but memorable attract screen, it stood out among its contemporaries because it was not pre-rendered game footage.

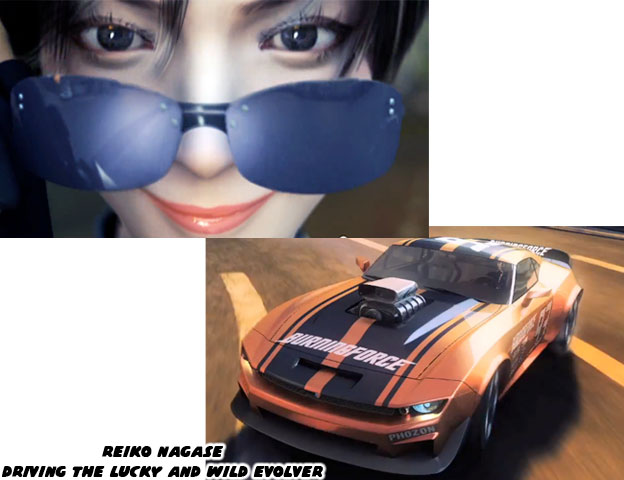

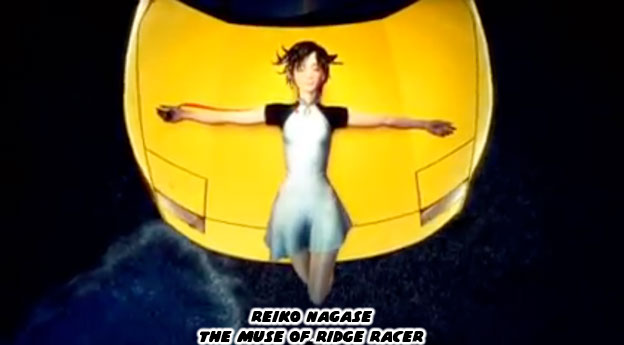

When Rave Racer was sitting idle it would start blasting its soundtrack and try to get the attention of arcade visitors. When they would look there would be a polygonal female model posing for fans. Her turnaround animation was inter-cut with images of race cars sliding around corners. It was one of the more innovative attract screens seen in that era. The star wasn't a typical race queen, not by any stretch of the imagination. With a new short haircut and sporting a leather jacket, shorts and a bare midriff this model was the archetypal "hot girlfriend." She certainly looked more approachable than the models wearing corporate logos featured in the previous games. She had actually predated the look used for Ai Fukami by a decade. This model did not have an official name but Namco would hint later on that it was Reiko from the original game. Her makeover was a hit with audiences. The new Ridge Racer team would continue to build an entire mythology of Ridge City around this character.

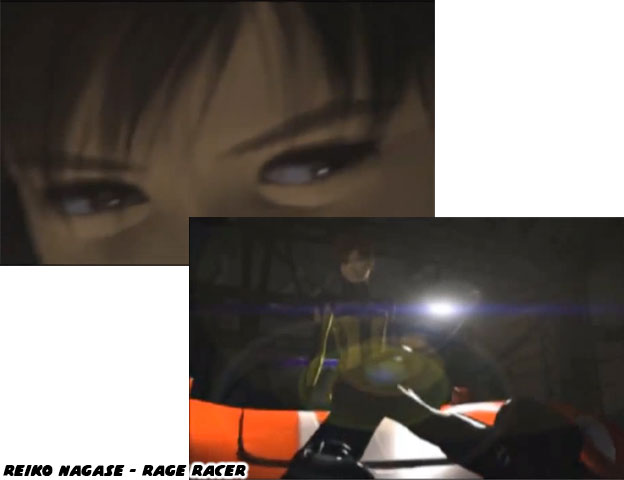

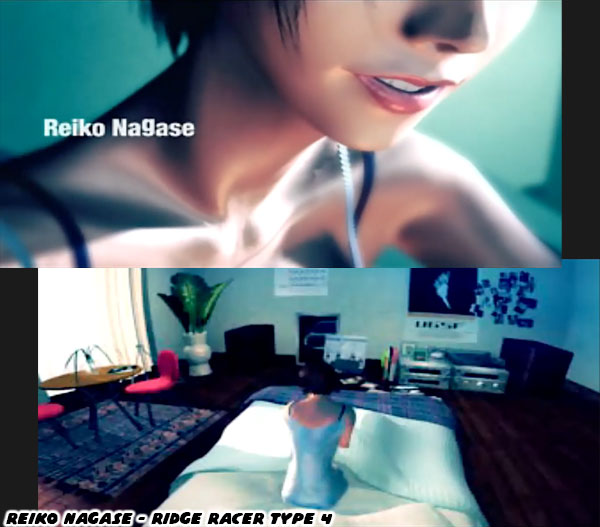

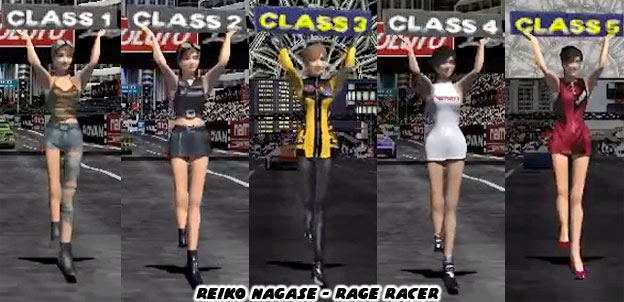

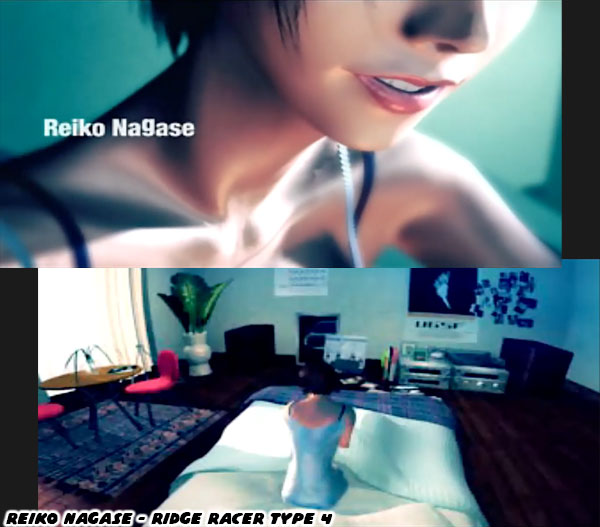

The studio had begun developing and adapting titles for the fledgling Playstation console in the mid '90s. This lead to Reiko becoming a more refined character. In 1997 Rage Racer introduced an entirely new side to Ridge City. It was as bold an experiment as Rave Racer was. The electronica soundtrack was still part of the experience but visually it was a bit more grounded in European architecture and gritty realism. It still allowed for the over-the-top car physics to sell the action. The short-haired race queen had returned and was given an official name. For the first time in Ridge Racer history audiences got a chance to see this character grow right alongside the driver.

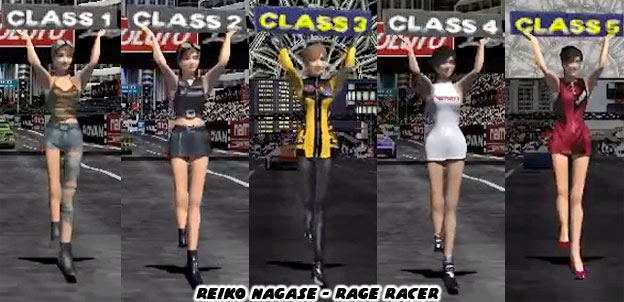

The model had started from humble origins, just like the player, and had to work her way up through the different classes. Rage Racer started off with slightly modified production cars, something that an enthusiast could do his or herself over the weekend without any sort of sponsorship. In those races Reiko was dressed in street fashion. She wore torn jeans and a tank top. The corporate sponsors has not yet discovered this "talent." As the player improved in the rankings and was able to afford faster machines and compete against bigger teams they would run across Reiko again and again. Each time her costumes had improved and her presence had grown within the community. She went from fantasy girlfriend material to supermodel status in the course of the game. Her modeling career had taken off in canon but was for a game not often recalled by the game players.

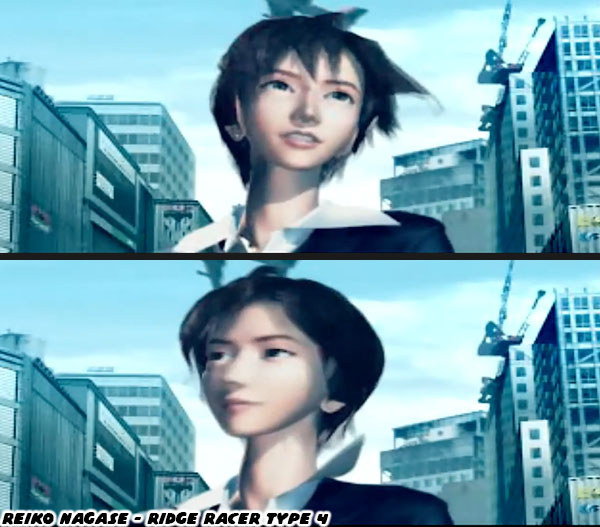

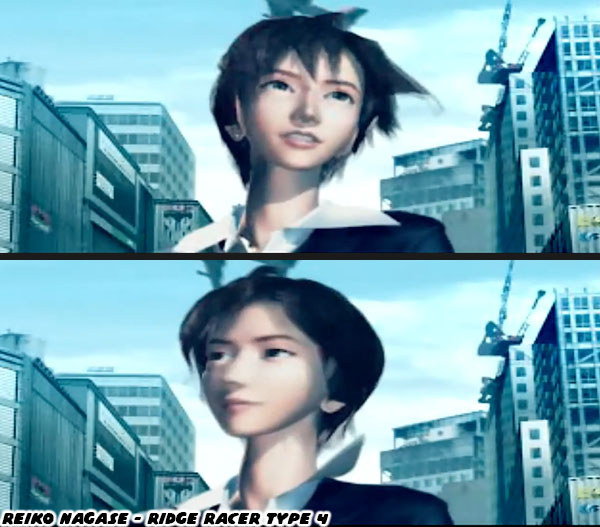

Kei Yoshimizu was the director of both Rave Racer and Rage Racer. He had been establishing Reiko's new look through the '90s. He had created her original models and animation and would continue to update the character over the next two decades. When he started he realized that the flat pixel models from the original Ridge Racer would have to be redone. He started modeling new characters in 3D but felt the crunch of a deadline fast approaching. Namco wanted to get some promotional material out with their new mascot. Kei didn't have a long-haired model to use for reference so he did the fastest thing he could. He shaved his face and took some pictures of himself to work from.

He scanned in the photos to create the original textures for the character. He retouched them to give him, or rather her, flawless skin, new lips and changed the jawline a little. The short, tomboyish hair was done out of necessity. Hair had been a stumbling block for many developers and animators. Kei didn't have time to figure out how to recreate the original flowing race queen hair in 3D. He thought it would be better to keep her hair short and a trend was established. Reiko could still be very feminine and even "girly" while promoting race culture.

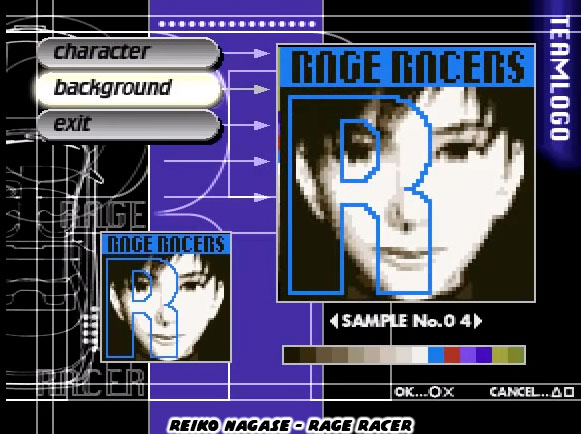

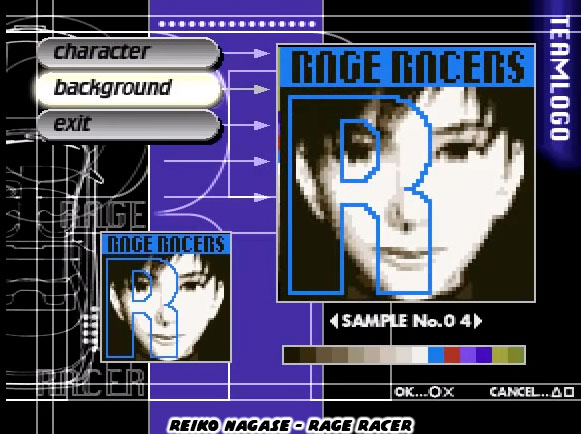

The revelation that Kei was the basis for Reiko shattered the dreams of some fans. They were hoping to find out that Reiko was inspired a real person but not necessarily a real man. This bit of trivia was not widely known to the arcade community let alone the greater gaming community. Undoubtedly many young men would have been heartbroken to find out. As such Namco was really finding that the virtual idol made for a great mascot. Her likeness was used for some of the pre-designed graphics that players could use as stickers on their cars in Rage Racer. The company would beginning putting the face of Ridge Racer out on ads in Japan as well as the US.

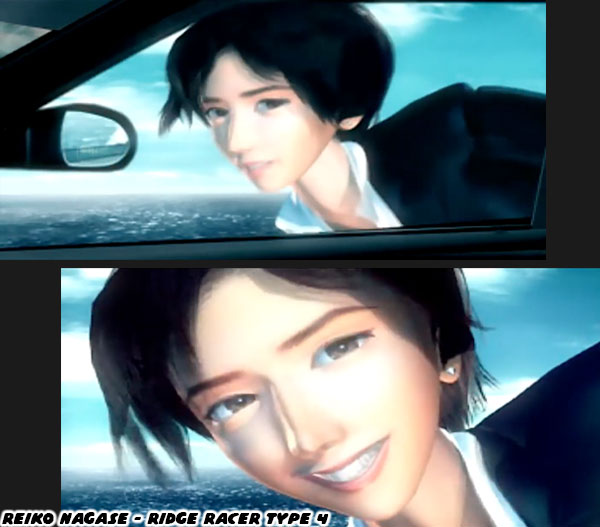

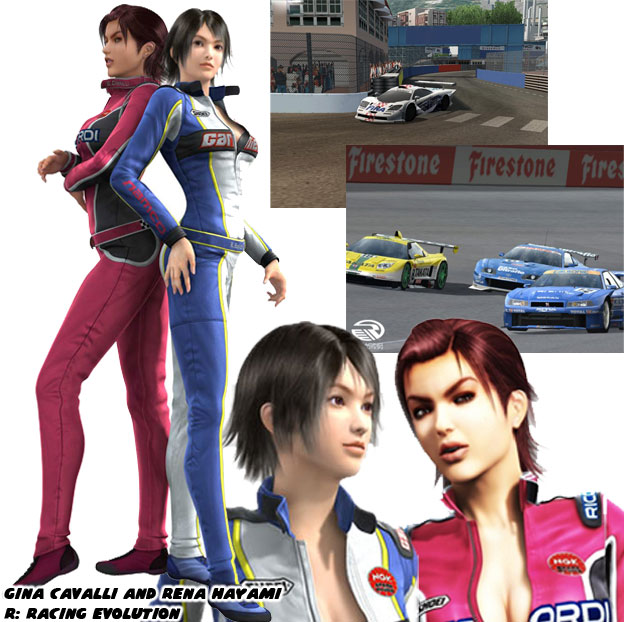

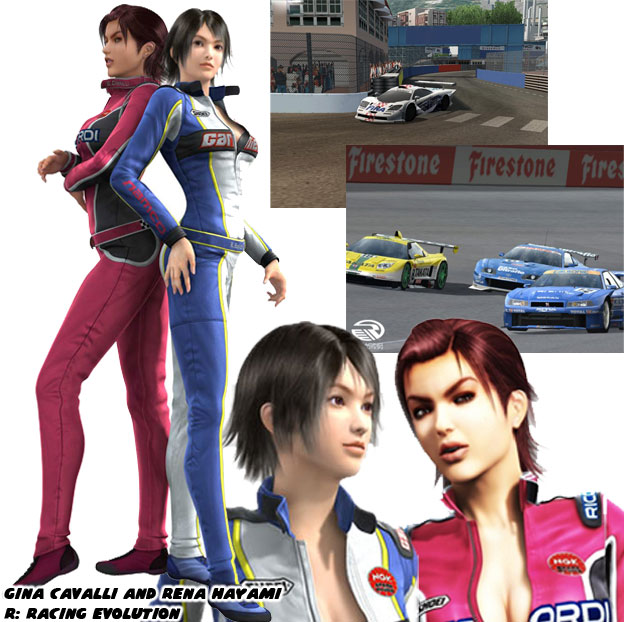

Despite the newfound popularity of the character Namco was not certain if she had staying power. The developer made sure to give Reiko a very strong push in Ridge Racer Type 4. They featured her on all the assets and promotional materials sent out to reviewers. Many of the media outlets in Japan and the US made sure to use a version of the character for their articles and even on the covers of their magazines. Yet no sooner did the studio do that than they dropped her altogether. Instead of casting Reiko in R: Racing Evolution they created a new idol that looked very similar to her named Rena Hayami.

In the intro for Ridge Racer V with Ai Fukami was retracing the steps featured in the attract screen of Rave Racer. The muse had disappeared almost overnight. It could be argued that the Ridge Racer series had its most turbulent showing during her absence. Was Reiko the glue that held the series together? The next blog will highlight the importance than one character could have on a series and an entire universe.

As always if you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!