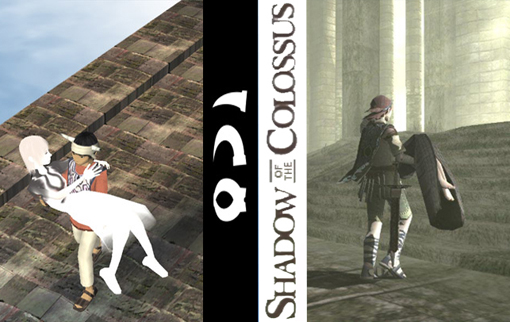

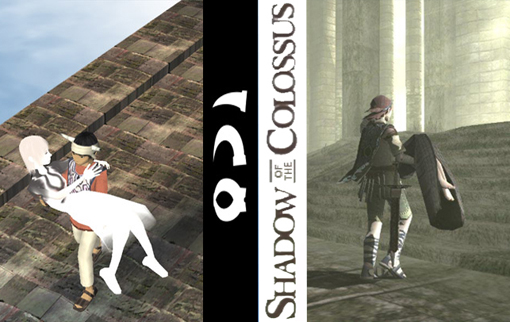

The announcement of a new Virtua Fighter at the 2024 Game Awards was a pleasant surprise. The only reveal I was more excited about was a new game from Fumito Ueda, and his team at gen DESIGN. These were the people formerly on Team Ico at Sony Studios Japan. Both

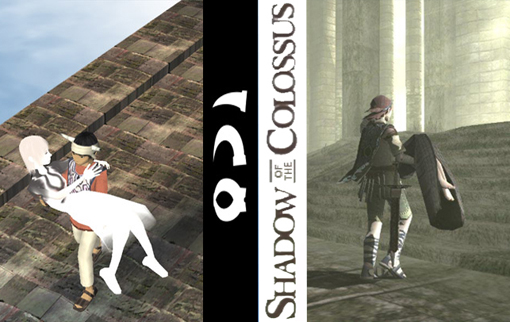

ICO, and Shadow of the Colossus were a revelation for me. The game reveals were also a little melancholy for me. A long time had indeed passed between titles. I’m talking about major life changes; new jobs, getting married, raising a kid before I saw another sequel. I began thinking of how much history I had with the games. I began thinking of how much the industry had changed throughout the decades. I especially began to focus on how my love of Sega games went back a few generations.

There was another reason why the game reveals made me reflect. You see in November of 2024 I celebrated my 50th birthday. It was a bittersweet time. A relative came down with a medical emergency in the fall of 2024. My wife sprung into action, and moved in to help take care of this person. The original plan was for a few days, maybe a week. That had turned into almost 4 months and counting. We were apart for our wedding anniversary, Halloween, my birthday, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and the New Year. The time, and distance had been heavy for us, especially with no reunion in sight. This health issue made me think of my own life, and mortality as well.

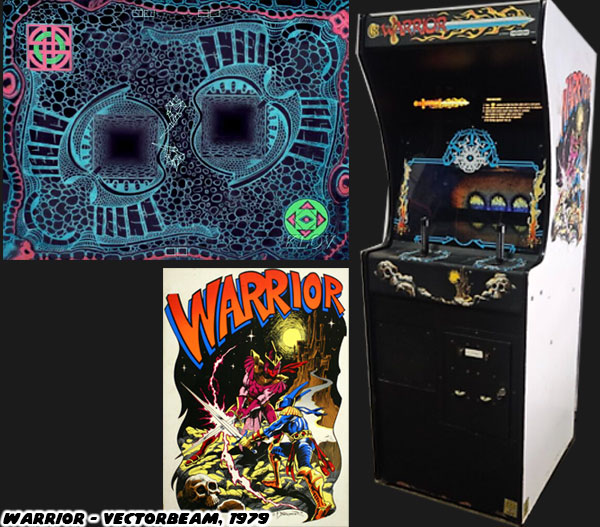

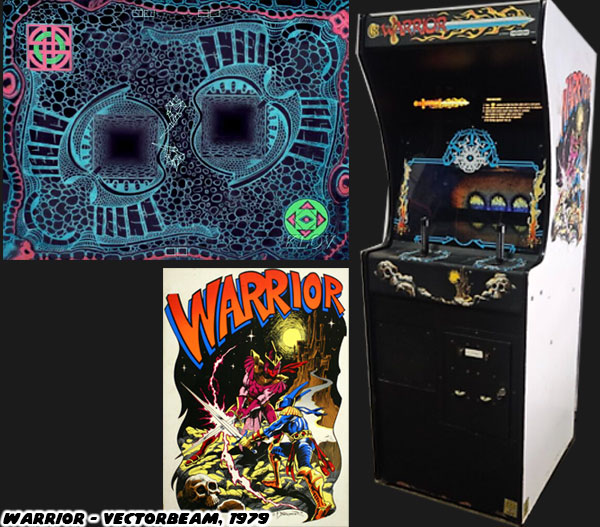

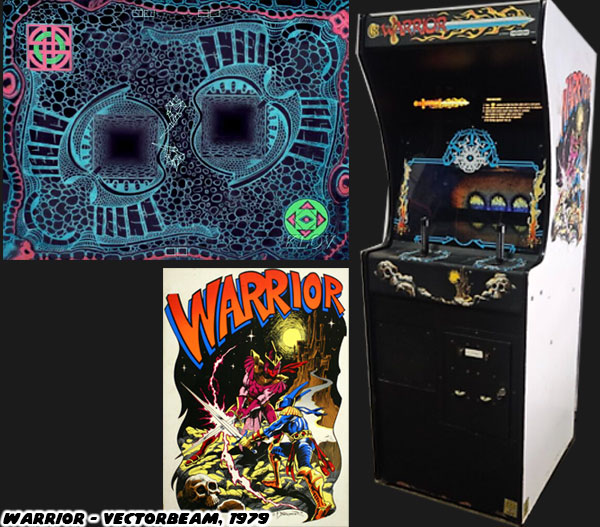

I realized that I’d been a fan of video games, and specifically fighting genre for almost as long as I’d been alive. Yet at no point did I ever think that it was time wasted. My first fighting game memory went back years before the creation of Street Fighter. It was the extremely rare

Warrior by Vectorbeam. I was five-years-old when it came out. The innovative top-down view, sword combat, and painted background of the arcade cabinet sparked my imagination. It also made me realize that fighting games could be more than a boxing sim. They could be about knights, karate masters, and even dinosaurs! I would argue that 1984 was the most important year for the development of the fighting genre. This was two years before the original Street Fighter, and the template of the

brawler was revealed through Renegade.

Punch-Out!!,

Karate Champ, Yie Ar Kung-Fu, and Kung-Fu Master all came out in ’84. Each influenced the studios, and developers that would create the modern fighting game. I was grateful that I had a chance to play through them when they debuted. In fact I was born at the perfect time to experience the peak years of the arcade revolution. The memories I had of the dozens of arcades I frequented, and hundreds of games that I’d played were irreplaceable to me. I would not have changed one thing about the time I spent playing video games. Especially not after I discovered fighting games. I was grateful for each, and every title that I enjoyed over my time on Earth. Knowing that Virtua Fighter was getting a reboot, and celebrating 30 years made me realize that I first played the game when I was 20-years-old. This also meant that the architects of the genre were getting old too.

The masterminds behind Street Fighter, Fatal Fury, the King of Fighters, Mortal Kombat, Killer Instinct, Tekken, Samurai Shodown, Virtua Fighter, and more were now in their 50’s, and 60’s. A few of them were retired, if not considering retirement. This meant that some games, and entire genres could potentially die off. It was important for the publishers to have younger talent take over the projects. New directors, and producers to be just as passionate about the genre as their mentors. This ensured that the games would continue to grow, evolve, and remain fresh.

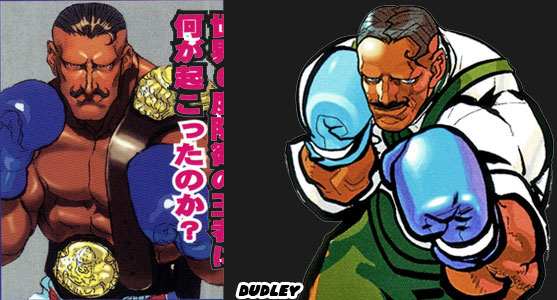

I wasn’t a fan of Yoshinori Ono as the producer of Street Fighter IV, and V. I did appreciate his enthusiasm, and how he pushed Capcom to bring the franchise back after almost a decade after SFIII had been released. I believe that his eye would have worked better on a series like Vampire / Darkstalkers.

I was much happier with the team putting together Street Fighter 6. Mr. Nakayma, Mr. Matsumoto, and Mr. Tsuchiya had been with Capcom for years. They were ready to slide into their new roles, and take over the franchise. They managed to honor the legacy of Street Fighter, Final Fight, and bring in elements from 40 years of Capcom games without breaking the continuity of the series. They were able to update the game play, the elements that modern audiences expected from a video game, and even help bring new players up to speed. Most important they were also young. They would be able to carry their passion, and insight to SF for years to come. Not every classic series had these types of directors. Many of those games faded away from relevancy once their creators left the studio.

It may seem hard to believe but Virtua Fighter was such an important game that it changed the direction of the industry. In 1991 Capcom already created a global phenomenon with Street Fighter II. This made every studio in Japan, and the US start developing their own fighting games. A few years later Sega demonstrated that 3D would be the next step in the process. Companies that weren’t already developing their own 3D engines were at a loss. They could however license the work from Sega for their own titles. Some gamers may not know this but the

original Dead or Alive arcade game was built on the Model 2 engine, the same one that powered Virtua Fighter 2. The game’s creator

Tomonobu Itagaki had been described as a creep. It was no surprise that the girls in his fighting game had very bouncy breast physics applied to their models. He left Tecmo with many of his Team Ninja developers to strike out on his own. He eventually closed his studio in 2024. Dead or Alive managed to make it to DOA 6 which was released in 2019, with no word on another sequel.

That was not to say that Virtua Fighter was a superior experience to Street Fighter II, or many other sprite-based fighting games from the early ‘90s. The game play was not as quick, or as intuitive as audiences were used to from 2D fighters. Visually however Sega was offering something that was unlike anything else in the arcade. When you saw a Sega 3D engine in a

racing game,

air combat, or

Star Wars title then you immediately took notice. The visuals were so unlike anything else in the arcade that players were instantly drawn to them. In the early 1990’s 3D human models were still in their infancy. People were so blocky that the team at Sega referred to them as robots. They looked embarrassingly like somebody wearing cardboard boxes. To my knowledge the only fictional style in the original game was given to the ninja Kage-Maru. Yet it was still inspired my elements of actual ninjitsu.

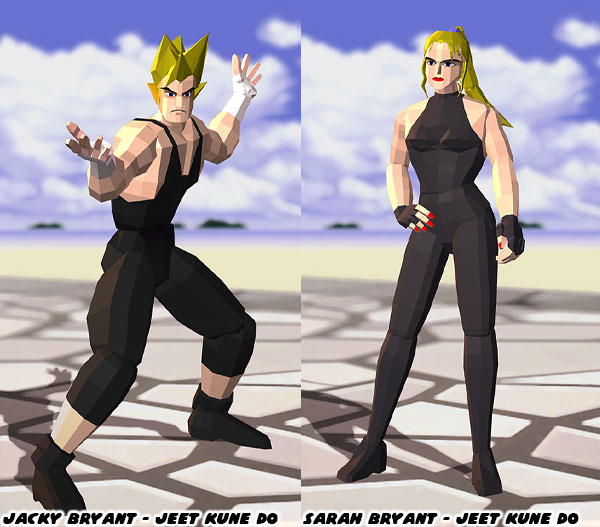

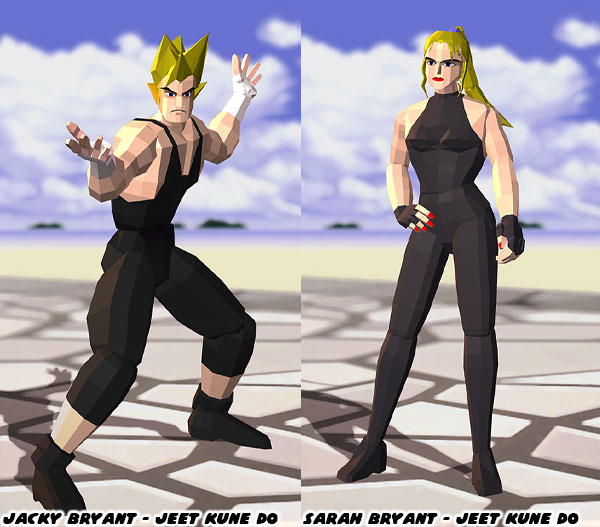

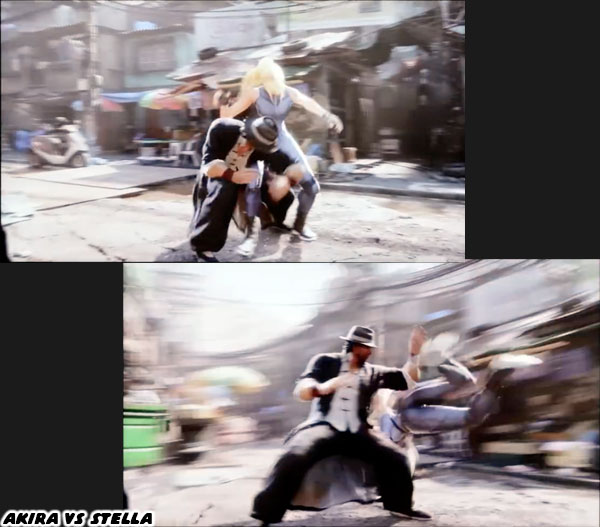

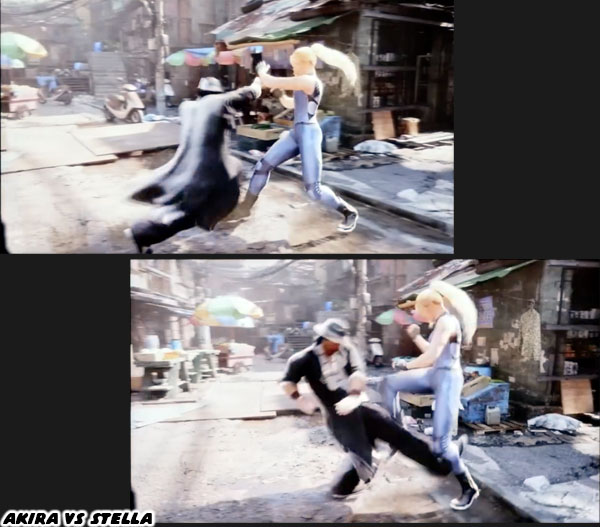

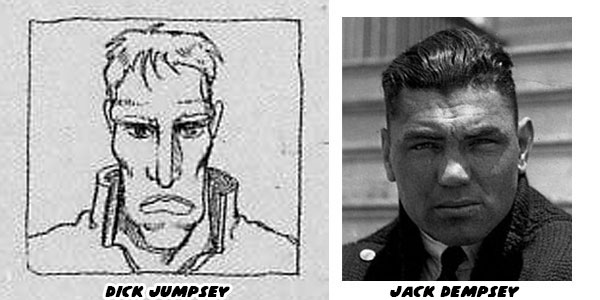

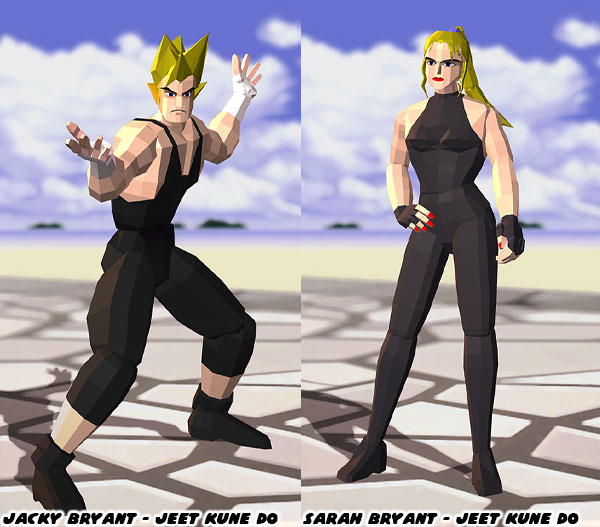

Series creator Yu Suzuki knew what he was doing. Smooth, perfect 3D characters were not his goal. The team at AM2 were using every trick at their disposal to create a solid engine that they could improve upon. Knowing that people would look more realistic in every future iteration. The team also focused on creating a library of characters that represented a broad spectrum of fighting arts. Each sequel would introduce another fighting style. The brother, and sister team of Jacky, and Sarah Bryant used Bruce Lee’s very own Jeet Kun Do aka the Way of the Intercepting Fist. They were fast, flashy, and designed to appeal to western audiences. They were not the only relatives in the game.

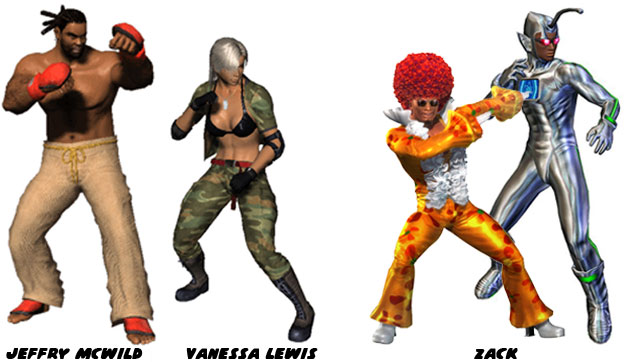

The Chinese father, and daughter pair of Lau, and Pai Chan were central to the story as well. They were a sort of classic martial arts cinema archetype that was universally understood. Anyone that approached the game could tell that they used some form of kung-fu. Then there were the two heavy hitters in the game, the ones that I favored. The Native character Wolf Hawkfield, and the Caribbean Jeffry McWild. Although Wolf was light skinned it was nice to see some form of Native representation in a game. The same applied to Jeffry. The duo were so popular that they would appear in future pro wrestling games as well.

With a cast, and engine in place it was only a matter of time before the rival studios would have an answer to VF. The first would be Tekken. Namco had been going back-and-forth with Sega on everything they released. Just because they went from 2D sprites to 3D polygons didn’t mean the rivalry would end. There was not one genre where the two publishers did not have direct competition. Tekken floored audiences with their textured polygons. These stood apart from Sega's flat shaded polygons. Visually Tekken looked like the superior game, even if the frame rate or other elements weren’t as well done as VF. Each sequel from the two companies felt like a call, and answer.

The differences between the two games were tiny, but their impact to the community was tremendous. The four years from the release of the first VF in 1993 to Tekken 3 in 1997 was a technological leap. The improvement on textures, engine, animation, and frame-rate was apparent in the

Virtua Fighter 2 arcade intro. Virtua Fighter was focused on realism rather than the more fantastic Tekken. By the time Sega released VF 3 the characters could not only turn their heads to follow opponents, but even turn their eyes as well. Not to mention when they stepped in sand, or snow they left tracks. Doing tiny things like having head tracking, showing damage, and even breathing was an unheard detail in any other game. Suddenly Capcom’s reputation as the best fighting game developer was in doubt.

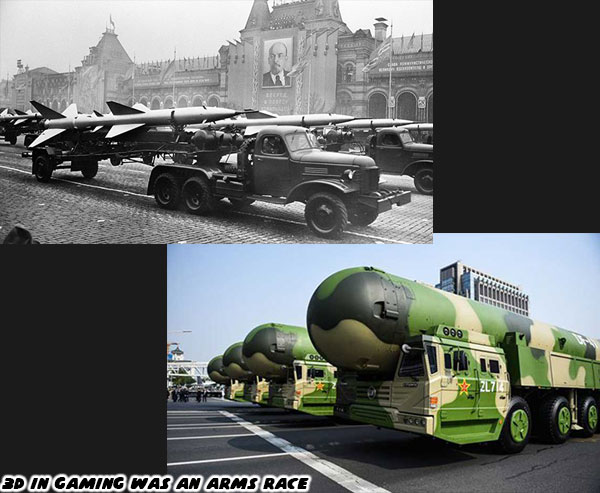

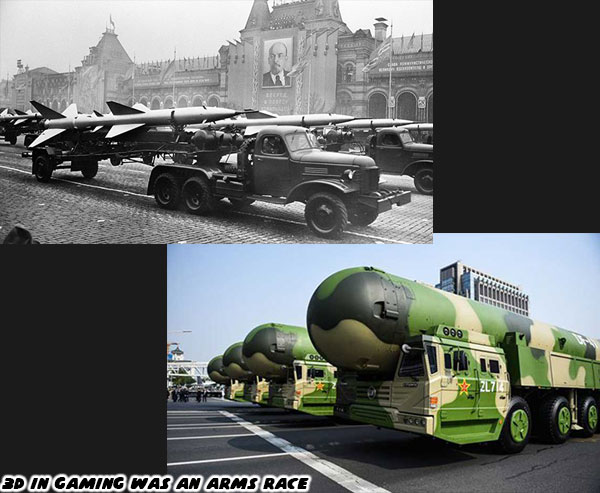

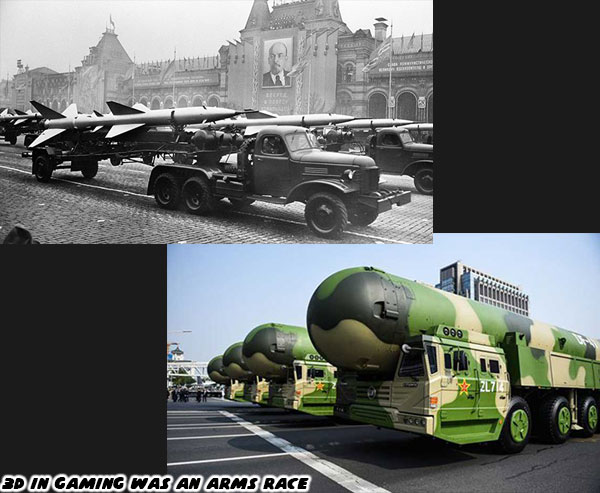

Sega, and Namco had turned the fighting game community upside down in the mid-‘90s. This made every major publisher increase funding into 3D R&D, helping push the entire entertainment industry forward. What many people didn’t realize was that Sega, and Namco relied on outside contractors to help create next generation 3D graphics. Namco built their System-22 engine on simulator tech from Evans & Sutherland. Sega developed the Model 3 board with military-level technology from General Electric Aerospace Simulation & Control Systems. The two publishers created an arms race. This applied equally to arcade, and console developers. Whichever company could bring 3D graphics home for a reasonable price would win the war.

Sega was able to bring some 3D games home. They made a decent 16-bit adaptation of VF using the 32-X add-on for the Sega Genesis. A closer arcade-quality version would appear on the 32-bit Sega Saturn as well. Not to be outdone Namco partnered with Sony to create an arcade-perfect version of Tekken for the new Playstation console. Fighting games were not the only titles to help move consoles, but they certainly helped. The shift from 2D to 3D was pushed along thanks to Sega and Namco. More than 30 years had now passed. Mr. Harada, and his team were still keeping Tekken alive. Sega had drifted away from many of their biggest hits through the 2000's and 2010’s. How would Virtua Fighter become relevant once more, and especially with Mr. Suzuki talking about retirement? We’ll talk about it in the next blog. Were you a fan of 2D fighters, 3D fighters? How long had you been playing video games? I’d like to hear about it in the comments section. As always if you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!