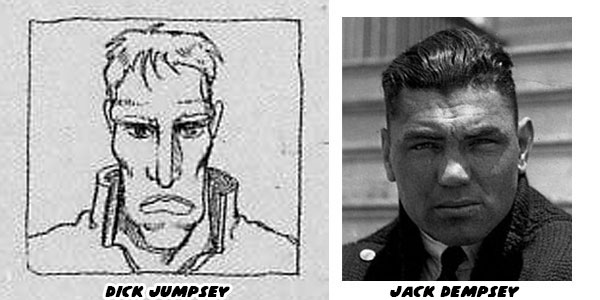

It seemed that substance did matter to the core fighting game audience. Respect for the genre and the audience was good for the long term success of a franchise. The gameplay, control, and animation featured in the Street Fighter series was better presented than any other series. The characters featured within had become more iconic than those from any other game. Most players were familiar with Balrog, the name of M. Bison in the USA, They knew that he was based on pro boxer Mike Tyson. However during the development of Street Fighter II there was going to be a boxer as a playable character. This boxer was named Dick Jumpsey. He was inspired heavily by Jack Dempsey, a prize fighter from the turn of the century. The stance, moves and techniques of those early legends like Dempsey were the stuff of legend, especially in Japan. Boxing was made popular in the manga and anime series Ashita no Joe (Tomorrow's Joe) and the more contemporary Hajime no ippo. The influences of popular culture on the decision to use a boxer and even how he appeared should not be underestimated. These elements have been influencing designers for decades. The Joe story would have been something that the team at Capcom had grown up with in the early 1970's while the Hajime no ippo story would have been a contemporary manga running parallel to the development of Street Fighter II in the late 80’s.

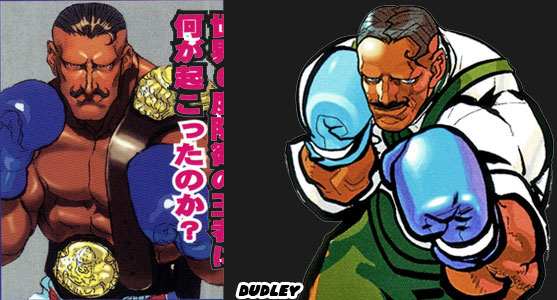

A Dempsey-inspired character would not appear until years later. Dudley, featured in SF III was a gentleman boxer whose timeless qualities made him an instant success and a perfect fit for the SF universe Dudley could be argued as a complete vision for the Dick Jumpsey character abandoned previously. The "Dempsey Roll" was a technique that the actual Dempsey used to dodge under opponents and throw a flurry of punches while bobbing and weaving. This was a rarity as a real life technique rather than a fantastically impossible one would end up in a videogame. In anime form the move looks fantastic, in game form it was doubly so and could be used in combos with relative ease. Dudley's Rolling Thunder in SF IV was based largely on the Hajime no ippo version of the attack and makes for a very visceral super. Dudley may not have been based on a real person but he had a better reputation as a fighter than Method Man.

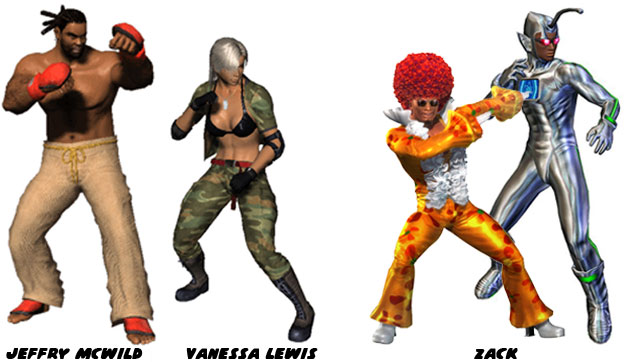

Hip Hop was influencing global culture at an alarming rate. From the rise in New York through the '70s through the exposure on mainstream media in the '80s Hip Hop had pushed for a major shift in pop culture. Blacks were becoming very prominent influences. The points of reference that the Japanese were using to recreate blacks and black culture had evolved greatly between the time the first and second Street Fighter games were released. The Japanese didn't always manage to keep up with those changes. When that happened the studios ran to two extremes of depiction for black characters. They were either over-the-top, boisterous and flamboyant characters. Or they were the opposite, completely devoid of personality and simply a dark skin tone on a 3D model. Jeffry McWild was the first black polygon-based character in a fighting game. He was one of the original faces in Sega's Virtua Fighter released in 1993. The character was neither thug nor cop. He did not have a basketball, nor did he dance. He was a powerful fighter from the caribbean that muscled through opponents with his unorthodox grappling style. Jeffry was a rarity in fighting games, especially for the 3D fighters. He had a personality, proud and confident but not silly like Dee Jay. It was unique that the two characters came from the same region but had vastly different design cues and presentations. The Japanese had demonstrated once more that they could have tremendous respect for black character designs. In 2001 Sega released their second black character in the series. Virtua Fighter 4 added Vanessa Lewis, the first black female mixed martial artist in gaming. She was similar to Jeffry in that she had striking and grappling moves but past that had zero personality. She was a stunning 3D model that was simply designed to appeal to male players. She demonstrated that the developers, while respectful of their audience, had less of a cultural understanding about strong black female characters than they had of black men.

Tecmo licensed the Virtua Fighter 2 engine from Sega when they started their own 3D fighting franchise, Dead or Alive. When Tecmo did not have a point of reference for an acceptable personality trait among the black community they made one up. The character Zack was a DJ that had entered the fighting tournament. He was not a Hip Hop DJ but seemed to be a flamboyant party DJ. To be honest he was never shown on the turntables in the series. Zack became obsessed with fame and attention and became more and more outlandish in each revision of the game. Absurd would not even properly describe the character, he went well beyond the excess of Dee Jay or any other character mentioned thus far in the series. Zack was not representative of black culture, Hip Hop culture or even Western culture. The basis for the character could be likened to Dennis Rodman, the eccentric NBA player. Yet Zack was simply a clown, a buffoon that happened to have dark skin. The defense once more would be that the character made sense within the context of his game and was a satire of typical character designs in a fighter. It was not a surprising defense of the series considering that the title was famous for its jiggling breast "physics" and objectification of its women characters.

There was a world of difference between Jax, Dudley, Jeffry, Dee Jay and Zack. Developers, publishers and even gamers may have dismissed the relevance of the designs over the past two decades but something had to be said. It was a duality that the industry and audience observed about gaming. Players wanted the mainstream culture, and especially the mainstream media to identify games as art. However when questions were raised about games being too violent or sexual for some audiences then it became an argument about entertainment and freedom of speech. The industry and the gamers themselves could argue the fundamental rights protected by the First Amendment, however they seemed to do that when it was most convenient to them. Gamers were passionate about their favorite titles and characters but only when it served their own interests. Many did not want to infer or interpret any controversial themes within their favorite games or even question the developers. There were many fighting game fans extremely passionate about the genre but to not question the characters featured in some of the most popular titles would be irresponsible of them as consumers.

To say that Zack or Dee Jay were just game characters and appropriate within the context of their title would be an attempt to bypass the argument. Without a cultural touchstone the Japanese studios seemed to rely on trope. The patterns of minority character designs were starting to become demeaning to audiences. Yet none of the gaming outlets seemed to call the publishers on that. But again, if I looked for the bad in fighting games I would find the bad. There were positive minority role models in fighting games and videogames in general. Characters like Dudley, Jeffry and Jax were created by Japanese and Western studios to show that diversity was alive and well. Games could still be art and entertainment in equal measure and publishers could still be socially responsible to their supporters. The next blog will look at the recent character that Capcom tried to create out of Hip Hop culture, classic cinema and black sports superstars. As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment