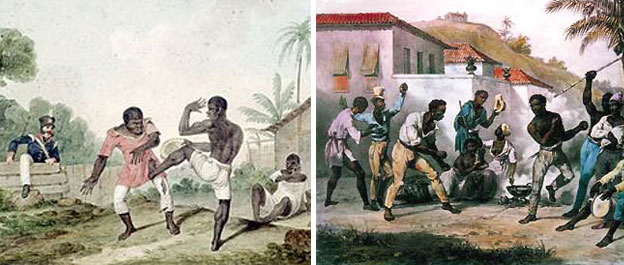

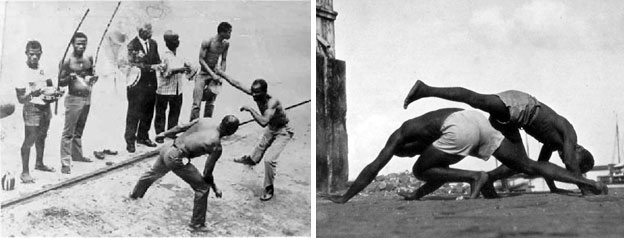

The slaves and natives kept authorities from discovering the true origins of the fighting art by making it look like a dance and a even a game. African drums were replaced by the native panderio (tambourines) and the berimbau (a stringed bow). The rhythms or toques played by the musicians, usually made up of other capoeiristas, determined what style the session would be in. Some songs emphasized leaping and tumbling moves, others focused on quick moves or trapping and still others forced participants to lay low and focus on upper body strength exclusively. The most dangerous form "Cavalaria" had knives, razors or machetes used by participants. In demonstrations two sticks replaced the machetes. The songs could also be used to signal the community of approaching authorities or soldiers. Practitioners would trade moves in a circle or roda. The constant movement of the dance would help make the practitioners hard to hit in a real fight. It would also teach timing, feinting and counter defense, which were all important elements in a battle. Capoeira became known as the Dance of War. It didn't take authorities long to figure out what the practitioners were really up to. The form was outlawed but many capoeiristas, not all African-slaves but also natives, ex-soldiers and immigrants kept the system alive. It became the secret fighting art of the New World. It was practiced in the back alleys and outskirts of town far from questioning eyes. Practitioners would call each other only by their nicknames or apelidos as to not tip off authorities to a real name or hideout even if they were to be captured.

Slavery was abolished in Brazil in 1888, decades after the Civil War in the US had ended. It lasted longer in South America because of the higher demand for slaves. The tropical climate was very good for year-round growing of crops and traders demanded a massive workforce. The indigenous people could not leverage enough support to end the trade with smaller nations or European partners. Those in authority did not want their economy or power structure to collapse so they did whatever it took to keep it running. When slavery ended capoeira finally came out of the shadows and became ingrained into Brazilian culture. Practitioners acknowledged the African roots of the art but also understood that it had changed considerably in the 300 years since the first generation of slaves had arrived. Brazilian natives, European immigrants and Caribbean islanders had all helped shape the fighting art and keep it alive.

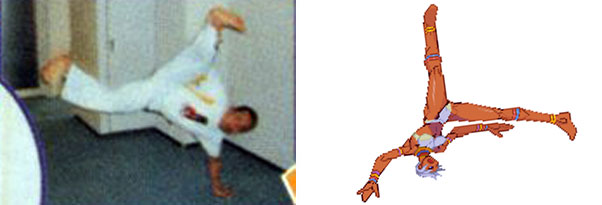

Capoeira would look great in a video game but there was one major problem. The system was much more fluid and rhythmical than the other arts. Karate looked absolutely stiff by comparison. In order to be accurately represented in a game it required hardware capable of displaying hundreds of complex animations on the fly. The early fighting game engines were woefully underpowered. They could only show a handful of frames of animation and had relatively small sprites. By 1997 both Capcom and Namco had developed powerful game engines that were up to the task. The CPS-III engine by Capcom was sprite-optimized hardware. It allowed developers to work with a more robust palette of colors, larger pixels and characters whose animation frames had gone up exponentially. Namco by comparison was working on 3D hardware. The System-12 unit they had developed created stunning animations on complex models with detailed textures and lighting effects. The characters both studios introduced set the gold standard for capoeira characters in a game.

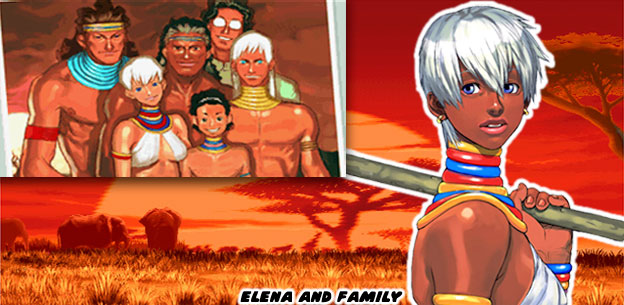

Elena was the playful long-legged African girl created by Capcom. The developer had rotoscoped one of their designers, Daigo Ikeno, who actually practiced capoeira in order to make the animations look as fluid as possible. Players could tell that the CPS-III hardware was leagues ahead of any other studio as they watched the hundreds of frames of animation given to Elena flow from one move into another.

Elena was designed with a combination of different native elements and animé influences. She had white hair and blue eyes, which was rare for a native African but seemed to run in her family. It was an interesting visual contrast, similar to the Aboriginal tribes of Australia. It hinted that Elena was actually of mixed descent. This made her one of the first mixed ancestry videogame characters. Black Orchid and her brother Jago from the 1995 game Killer Instinct were actually the first mixed ethnic fighters. They were from black and Asian parents but presented with Western comic book design cues rather than animé ones. The developers at Rare were keenly aware of their audience in the US. North, Central and South America had become ethnically diverse thanks to centuries of emigration. Asians, Europeans, Africans and Natives were not always mutually exclusive communities in the New World. Gamers that came from two different cultures sometimes felt that they could not identify with the main characters in their favorite titles. Even the strong minority characters only represented half of their heritage. Killer Instinct changed the perception of what was possible not just to gamers but to the industry as well.

Granted, Rare exploited many of the same trends when creating their cast that the other studios did. Orchid was a highly sexualized character. She was very busty and fought in heels while wearing a tight rubber dress. Her brother had huge muscles, like the other males in the cast, yet was still incredibly fast and flexible. The characters and gameplay was completely over-the-top and audiences understood that and appreciated the game for what it was. Killer Instinct was not meant to be a copycat of the games from Japan. It did not use hand drawn sprites but instead pre-rendered CGI sprites so that its graphics appeared years ahead of the curve. It did not limit the number of strikes that players could pull off and instead celebrated the 20-hit, 30-hit or even 90+ hit combo strings that savvy players could put together. Killer Instinct featured violent, gory or even comedic "Fatality" moves for the characters. Orchid for example would open her top, flash opponents and give them a heart attack. The game had become a reflection of what the audience desired in a fighting game. Players from Generation-X made up the majority of arcade visitors in the US. By '95 they had become older teenagers and wanted to see sex and violence in equal measure. Killer Instinct was a bold contrast to the sanitized experiences from Japan and offered more "mature" themes for these teenagers.

Jago and Orchid did not have an actual fighting style associated with them but instead had fictionalized martial arts moves. This was fine among players considering the duo were battling lizardmen, werewolves, cyborgs and aliens. None of those fantastic characters had realistic combat styles either. Gamers enjoyed the clash of styles and characters and for a few months Killer Instinct was the hottest title in the arcade. Once players had figured out all of the possible combinations and fatality moves the game tapered off in popularity. The characters and premise were fun and the uniqueness of the experience had built a strong following. Unfortunately the game lacked depth. The sequel failed to gain as much interest as the original. Within the community it became another challenge to figure out all of the combos, fatalities and secrets as fast as possible. Once that was done players went to other fighting games, and in some cases back to older fighting games.

The staying power of the best franchises was due to more than shock value, fancy graphics or massive combo strings. Great game engines and characters went hand in hand. Fantastic character designs that relied too much on spectacle rather than substance eventually sank the KI experience. Street Fighter tended to have a bit more forethought in their character designs and game engine. The developers had created a balanced game that would be easy for beginning players to pick up and yet gave advanced players a challenge to master. Killer Instinct had a steep learning curve by comparison. Beginning players could be brutally punished by opponents or the computer AI. This reduced the chance of repeat plays from those still learning the intricacies of Western fighters. The characters for KI were interesting but also lacked staying power. Gamers did enjoy the diversity of the cast but perhaps they were a little too generic. A black boxer, an alien made of ice and one made of fire… it was as if they were pulled from comic books and rival fighting games. Capcom on the other hand was crafting fighters that had more substance. In some cases they were inspired by real fighters, rooted in real systems and bore cultural cues when they could. It was easier for gamers to identify with these characters when it seemed that the studio respected their audience. The jewelry that Elena wore for example was similar to the layered necklaces of the Samburu tribe from Kenya. Her costume was anything but traditional though as it consisted of a very short bikini. The appeal of sexualized characters was not lost on the Japanese developers! Elena's stages in Street Fighter III featured the beautiful landscape of her home country. Wild animals, sweeping valleys and amazing sunsets framed the postcard-worthy Africa. Perhaps she wasn't meant to be a capoeirista but instead was supposed to represent Kupigana Ngumi.

Elena had set the bar for traditionally animated fighting game characters. Moreover she was a strong minority character of mixed ancestry. These design choices spoke to the community of players from different backgrounds. It was however a rival character that made the biggest impression with audiences. The next blog will look at the whirlwind character introduced by Namco and the style that inspired millions of gamers. As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment