Scott Stoddard and Adam Ford were the founders of Spiritonin, the independent game development studio. They had cut their teeth working on projects for Avalanche Software, Disney Interactive and other publishers. Both were huge fans of fighting games, especially the Street Fighter and Tekken series. Scott had actually practiced capoeira for a number of years. A back injury and family life kept him grounded but he never lost the passion for the art form. At the end of 2001 he put together a game called

. It was like a Shockwave tech demo. He converted 3D models into sprites for his newly created game engine.

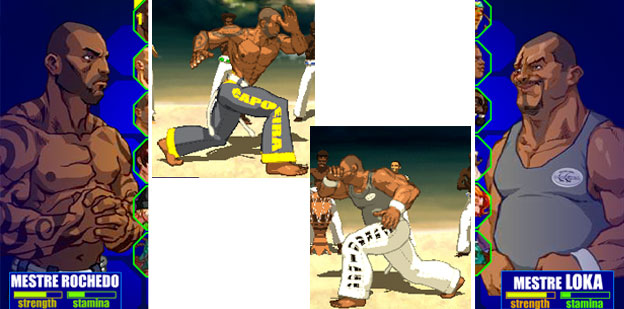

The animation was okay and the control was pretty good but sluggish when compared to any arcade or console fighter. The game featured two characters on one screen. There were none of the fancy level details, like scrolling or musicians in the background that appeared in subsequent titles. It was as bare-bones a fighting game on the web could get. The game actually had a plot which established the canon of the universe. Mestre Rochedo was honing his techniques for an upcoming fight with Mestre Zumbi. The fight was actually called a "Batizado" which meant Baptism in Portuguese. Students that were trying to earn their

cordas, the rope belts worn by practitioners, had to prove themselves by competing against an upper classmate. It was similar to the trials that karate practitioners had to go through in order to earn a new belt. Rochedo was one of the shaved-head characters featured in the series and Zumbi was the one with large dreadlocks. In the first game Rochedo was player 1 and player 2. Zumbi would not appear officially until the sequel.

A few months after the original game came out a much more polished sequel had arrived. Released in 2002

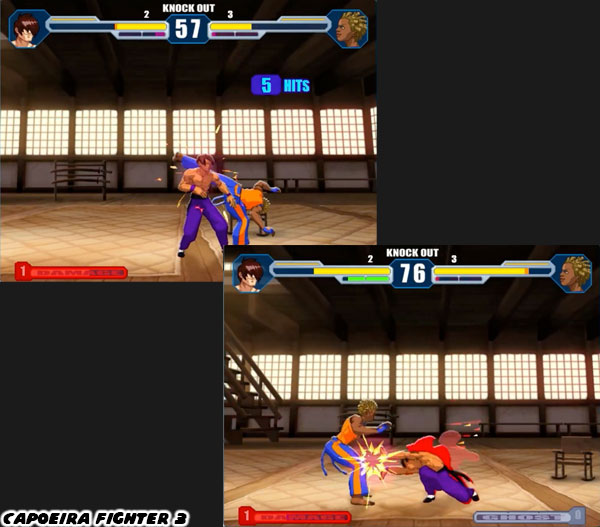

Capoeira Fighter 2 had laid the foundation for an amazing series. The game had much larger and more complex models. The game camera would actually zoom in and out to follow the players. The background was static but there were now musicians playing traditional instruments as well as the other playable characters clapping along in the background. It was as if the players were competing in an actual roda. The gameplay was still fixed in 2D like Street Fighter with similar mechanics. There were a handful of selectable characters, each with their own techniques and moves. Although the models were crude they were all distinct. The sequel had expanded on the story of the game. This time around Mestre Loka and Mestre Rochedo had teamed up to get their students ready for a batizado. Loka's rival Mestre Zumbi showed up to cause trouble. This meant that they all had to fight to defend the honor of their school. This small plot helped establish who the major players were in the game and what their motivation was.

It may have sounded insignificant for a fighting game, especially a web-based fighting game, but the story helped demonstrate the commitment that Spiritonin was putting into the series. All of the individual personalities began to come through as the characters, moves and details of the game had gone up considerably. The game had whites and non-Brazilians as well as minority characters in the lineup. The people of color were not treated like exotic or token characters but just as equals. All of the playable characters studied capoeira yet each had their own unique form. It was a refreshing change of pace as far as videogames went, especially fighting games. The diversity reflected the heritage of Brazil and the cross pollination of different cultural elements that helped transform Kupigana Ngumi into Capoeira.

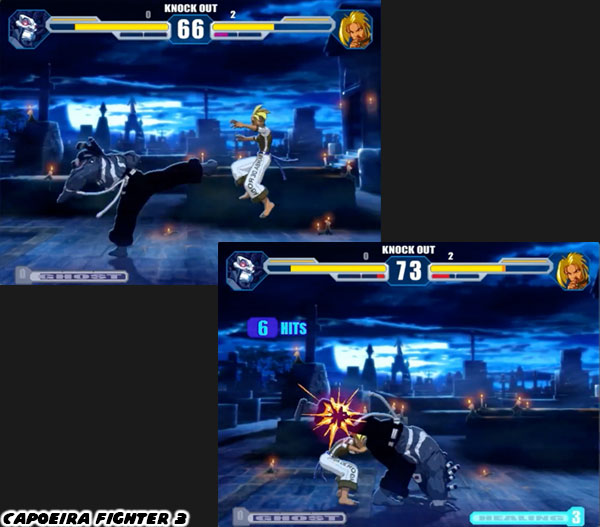

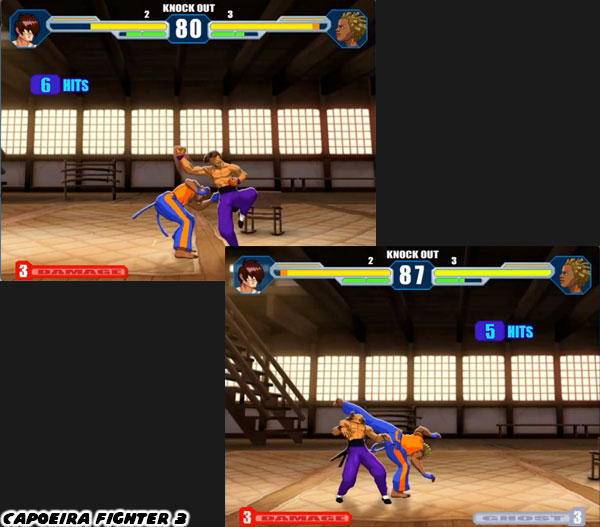

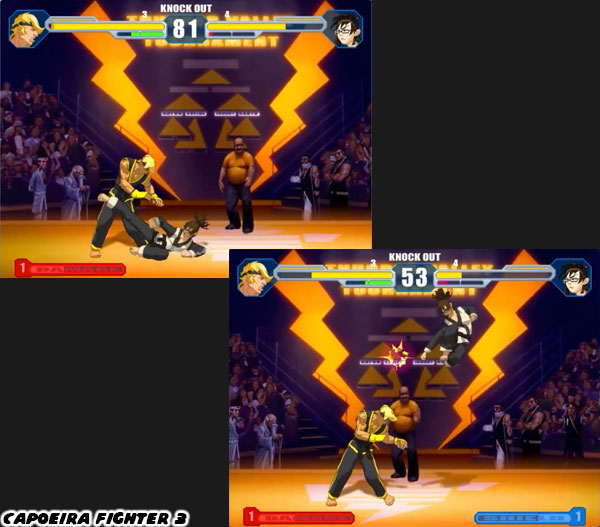

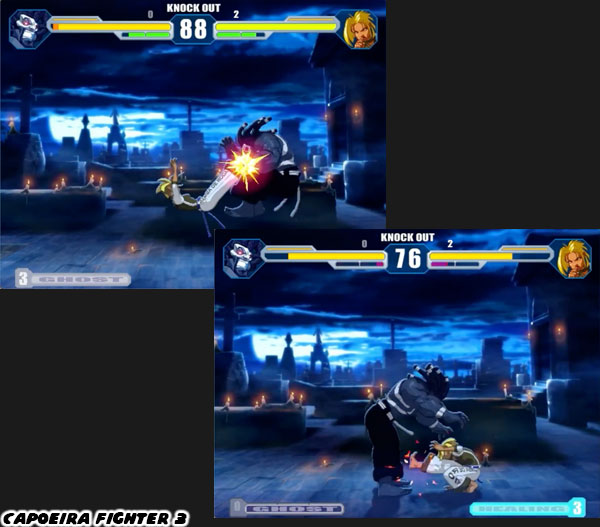

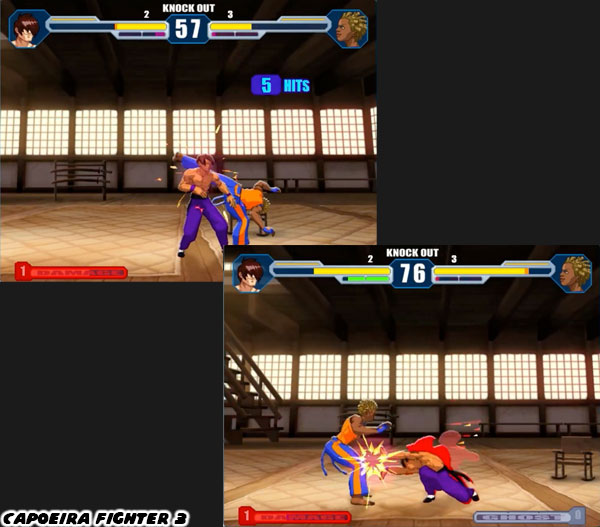

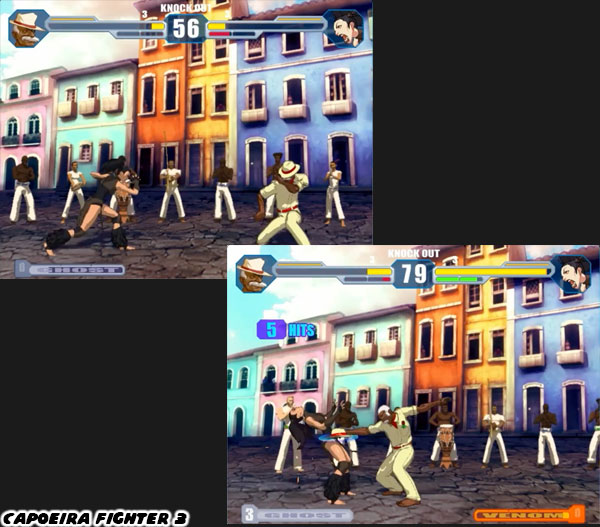

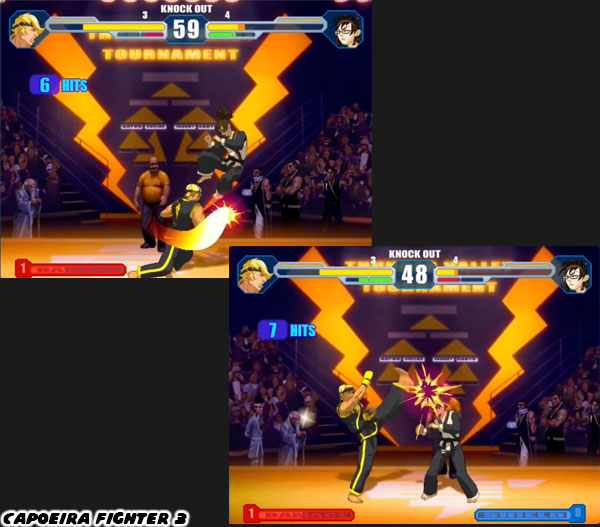

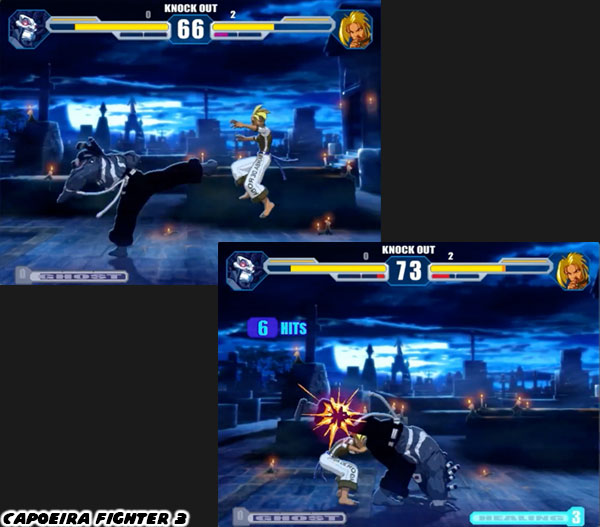

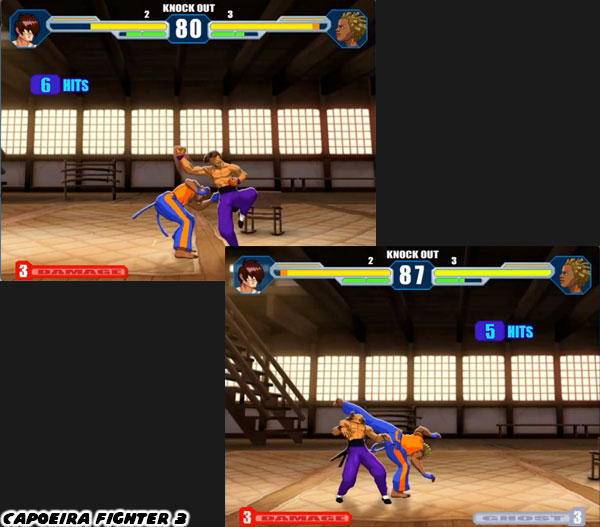

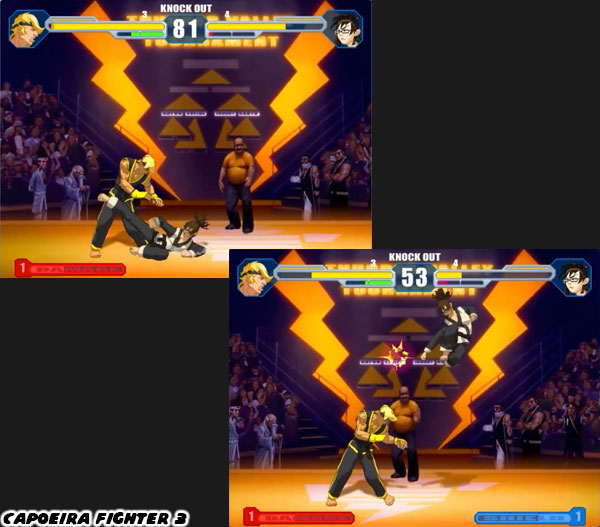

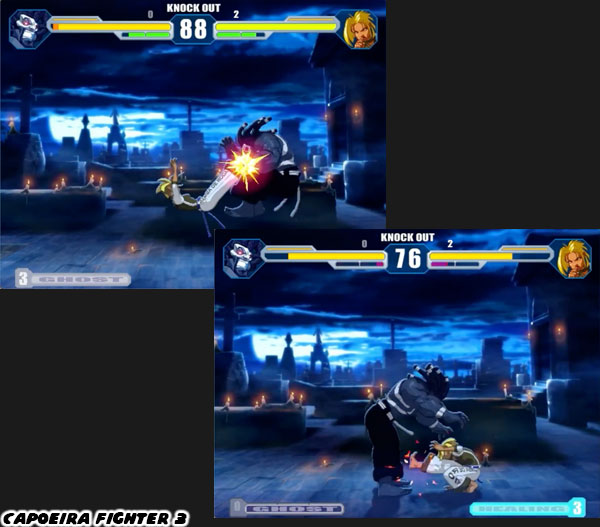

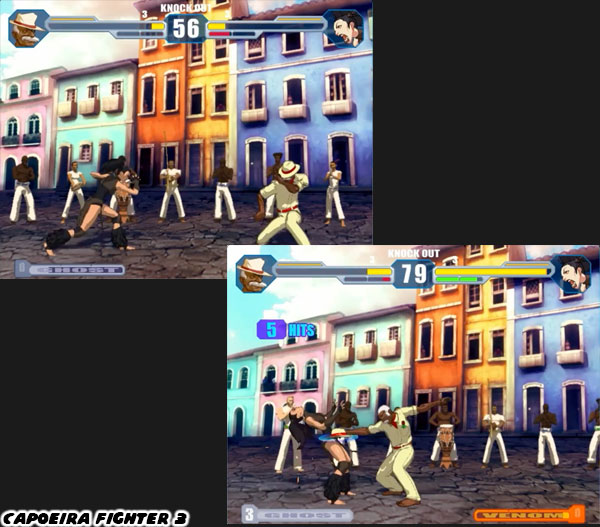

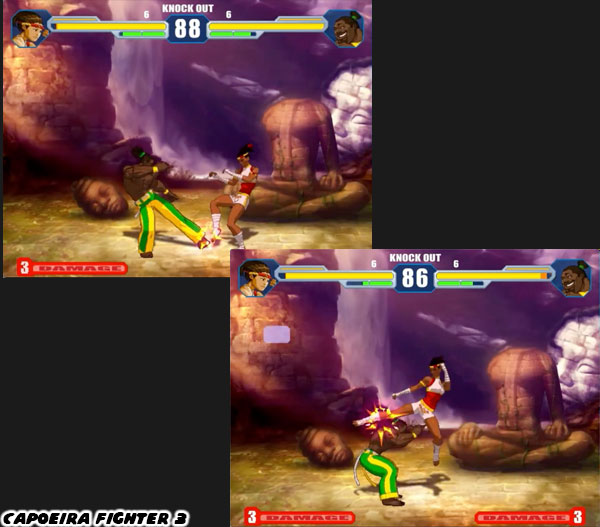

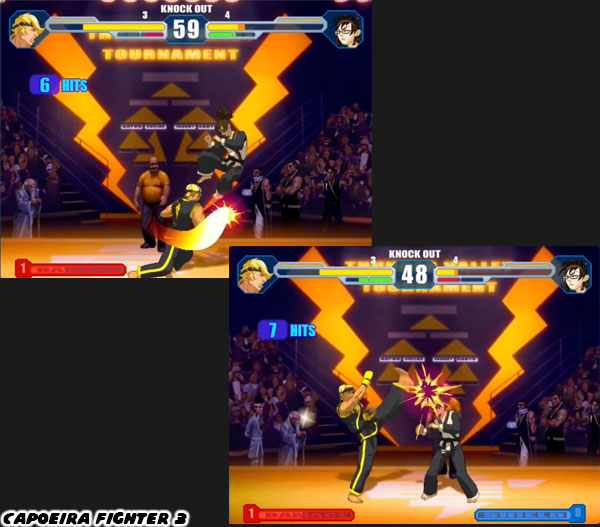

Things went quiet for a few years as Scott and Adam were working on another entry during their free time. The third game in the series could be considered the best web-based fighter ever made and one of the best fighting experiences period. Capoeira Fighter 3 (CF3) appeared in 2004 as a demo with a finished version not long after. Everything that was in the game was exponentially better than what had come before. Stoddard, Ford, their friends, coworkers and families all pitched in to help make sure that the game was worth remembering. The character models, animation, levels, effects, control, balance, music, sound and options were through the roof. Not that many people took notice of this detail but the game actually applied a lighting filter on the sprites. Shadows fell in the foreground or background depending on the placement of the "sun." Skin was shiny or dull, muscles and clothing were highlighted or dark, again depending on the placement of the light source. This was an amazing achievement considering that the game was created for the web on Shockwave, with a full version for the PC being available for purchase on CD.

It took a long time for Capoeira to become implemented properly in a game. It had actually required more work and research than any other Western or Eastern developer had put into the art. The tradition was still outlawed at the start of the 20th century. Just as blacks found it difficult to assimilate into society after the end of the Civil War in the US, the black Brazilians faced many of the same racial tensions, discriminatory practices, violence and oppression for decades after slavery had been abolished. They found it hard to gain acceptance or make headway into positions of power or respect. Capoeira was the one tradition they could hold onto and keep alive despite attempts to suppress the culture. The practice was gaining support in small communities and by 1937 the practice was tolerated by most non Afro-Brazilian towns. By 1953 it was no longer outlawed across the nation. Gamers should be thankful that SNK helped introduce the formerly forbidden art to gamers in 1989 and that by 1997 both Namco and Capcom helped it gain global visibility. In 2008 Brazil declared Capoeira part of its Cultural Heritage. It was only appropriate that the full version of Capoeira Fighter 3 was released in 2008 as well to further educate gamers to the Dance of War.

The game oozed style, Scott Stoddard and Adam Ford had created it as a love letter to the genre. It had pulled many elements from Street Fighter Zero / Alpha but with hints of the King of Fighters and Tekken series thrown in for good measure. To be fair the game also gave a nod to the characters, music and even locations featured in the cult martial arts film "Only the Strong" and even the 1977 classic

Cordao De Ouro "Golden Cord."

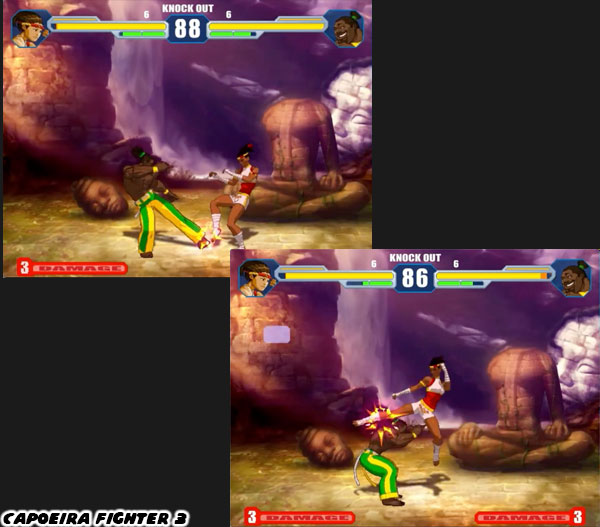

All of the characters introduced thus far had returned in Capoeira Fighter 3. Each of the characters was far more developed and distinguished. The size, scale, body type and even color choices applied to the characters was done with forethought. For example the colored cords that the characters wore reflected their rank and were worked into the theme of each costume. The bold primary colors placed on the cords were reflected on the clothing worn by some of the fighters. The use of primary colors to help identify characters had been used to great effect in Street Fighter II more than 20 years prior. Ken wore red, Ryu wore white, Guile wore green and Chun-Li wore blue. In CF3 Furacao (hurricane) wore yellow, Santo wore green and Perereca (poisonous tree frog) wore white. All of the women in CF3 were also dressed more realistically as well. None sported the bikini of Elena or the revealing costume of Christie Monteiro. Their costumes were functional yet form fitting so that they still accentuated the curves of the females.

A person might think that the gameplay would be very redundant with the number of capoeiristas but no two shared the same moves, combos or special attacks. Capoeira, like kung-fu and karate had hundreds of variations. The strikes applied to each character fit their personality as well as their body type. The muscular characters like Zumbi and Maestro had power moves which relied on tremendous upper body strength. They dealt a lot of damage with a few strikes but tired quickly. The smaller female characters like Coelha (named after a bunny rabbit) and Perereca did not do as much damage per attack but had lighting speed and did not tire as quickly.

The diversity of the characters could not be understated. There were 15 unique capoeiristas (16 including a special version of Zumbi). In addition there were 13 other "World Warrior" type characters that represented other fighting styles like Muay Thai, Tae Kwon Do and boxing. It was not the sheer number that made the game unique but instead the showcase of figures. In other fighting games the playable characters were always roughly the same size and body type. They never had an ounce of fat on them and were never too short or tall. Capoeira Fighter 3 had every skin color and body type that a person could imagine. The various tones and shades of skin suggested that several characters were of mixed marriages, mulatto or even native.

Very few games before or after had put as many minority characters in the roster. Very few games had ever put minorities in prominent roles for the accompanying story. The lineup featured tall, skinny, fat, short, muscular and average build body types. Even the heroic Mestres could not have been more opposite. Rochedo was tall, tattooed and muscular whereas Loka was shorter, stocky and wore a tank top that covered his paunch. Loka also sported very nasty cut through one of his eyes. The character had lost it

in a maculele or machete battle. The dangerous Cavalaria form of the art emphasized weapons and strong take downs which made Loka a tough fighter.

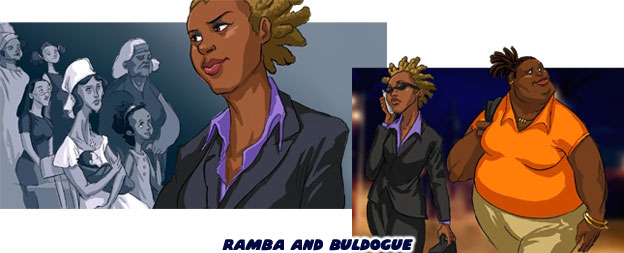

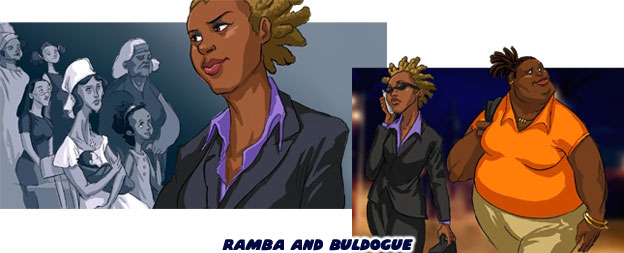

There was a character that reflected just about every type of gamer there was, including the young and old. None of them seemed feeble when competing against fighters in their prime. This distinction was important because the art form actually helped keep bodies healthy and limber even in old age. Something else to consider was that in most fighting games the token power character was a musclebound man. Zumbi and Maestro did fit the bill however one of the strongest characters in CF3 was a tall and heavyset woman nicknamed Buldogue. She didn't have the fancy tumbling moves of other characters, and she didn't jump very high for that matter. Instead she relied on more realistic open hand slaps, hip thrusts and kicks that could knock down walls.

The nicknames given to the characters was done in more earnest than tongue-in-cheek. Capoeira had been banned a few centuries prior in Brazil. Practitioners knew each other by nickname only. This protected the identities of the masters and their students. The nicknames were earned by peers, after a batizado and were closely guarded. These nicknames were the reputations that preceded the best fighters. The fighters could be named for their tenacity or lack thereof, like Stoddard's alias and playable character "Maionese," Animal names were revered because they were like avatars. Several fighters featured in CF3 were named after animals. Buldogue had the fearlessness and raw power to back up her nickname it was however her trademark yell that gave birth to her legend.

The other women in the game were just as unique and memorable. Some were shorter than their male counterparts and some taller. They all had a reputation and purpose written in canon which was revealed during the course of the game. For example Cobra was constantly pitting sides against each other. She was trying to get ahead in the criminal underworld that her father ran. Cobra had demonstrated that the women characters did not have to be heroes. Not only that but they could have as much influence on canon as any male character. Several of the main characters like Furacao, Zumbi and Jamaika were based on real people and the ones who trained Stoddard. It was funny because he turned some of them into villains.

Stoddard knew that it didn't make much sense in other fighting games that all of the characters knew each other or that they happened to be in the same country or town at the same time. So when he began writing the story for CF3 he made sure to reunite the characters under a common goal. This time it was Mestres Loka and Rochedo sending their students around the world to show off their capoeira skills. Zumbi was in hot pursuit of them. They had to prove their art against other fighting styles as well as each other. This meant that allies could fight each other through the course of the game and some could even switch sides. Male and female characters could be fighting for good or evil and the truth would only be revealed at the end of the game.

Some women had more altruistic goals than simply fighting for the sake of fighting. The tall light-skinned Ramba had actually been away from competition because she was busy at the university. She was asked by Mestre Loka to look after his students. She reluctantly agreed as it would be a good excuse to get away from law school for a moment. Along the way Ramba met Buldogue and offered her a better life. Ramba knew that Buldogue was a strong fighter but had never been given an opportunity outside of the roda. Buldogue had been used as hired muscle by other characters in the game and Ramba wanted to get her out of that life. She knew that the bruiser was actually respected by the community, especially the poor that lived in the

favela or ghetto. If she were able to get an education and become known for something other than fighting then Buldogue could become an inspiration for other women trapped by their situation.

Players were given a choice whether to team up Ramba and Buldogue or to play solo. The purpose of Ramba in the game was not to beat the main villain but instead to help guide those in need. If players completed the game solo then Ramba learned what she was really fighting for. She earned her degree but decided to open her own firm to help the less fortunate. If she teamed up with Buldogue she became a mentor and enrolled her in school while still working double-duty as a lawyer.

Strong, positive, dynamic, interesting minority female characters that didn't need to flash skin to get noticed? There had been few and far between for over 25 years. Designers in Japan and the US had lost focus on how they could introduce new faces without relying on pandering or stereotype. Characters could color the perception of gamers after all. When done in a positive light they could stop perpetuating stereotypes. Capoeira Fighter 3 had set a standard that would be hard for many developers to follow. Where I believe the game excelled was in creating a villain that would hold his own against the best fighting bosses ever designed. The next portion of the series will break from the issue of color to explore what it took to become infamous in the genre. As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment