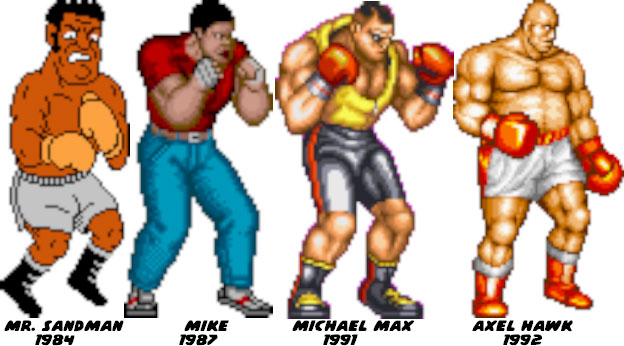

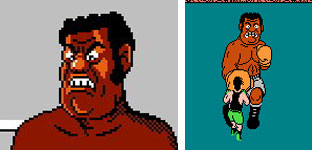

The original WVBA (World Video Boxing Association) Champion from the Nintendo game Punch Out!! Boxing would be pinned on many black characters from the earliest point in Japanese games. Some of the characters developed during the late '80s and early '90s were done as an homage to Mike Tyson. He was going through opponents at a feverish pace when he turned professional. Near the end of his reign other black athletes began to replace him. Axel Hawk was written as the mentor of Michael Max (another Tyson clone) from the Fatal Fury series. Axel was a nod to George Forman who made a comeback at the age of 46 and recaptured the heavyweight championship of the world 21 years after he had originally won it.

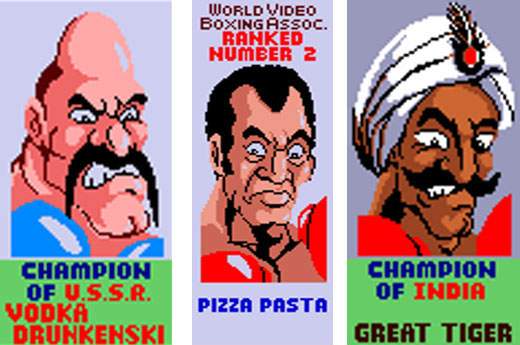

The game was also released in 1984 but had a reputation for its ethnically stereotypical characters including the Cuban Piston Hurricane and Italian Pizza Pasta. These were meant to be taken as a joke by the Japanese developers. Many game fans did not find too much offense in those characters however that changed with the introduction of the Vodka Drunkenski in Punch Out 2. The Russian was renamed when the game was translated to the home consoles. His bottle of vodka had been replaced by a soda bottle. Mr. Sandman was different though. He did not have any gimmick or racially biased name. There had been professional black fighters that also went by aliases like "Sugar," "Hitman" and "Dynamite," so the Sandman seemed to be a good fit. The character was deadpan serious, as one would expect a World Champion to be. He required perfect timing to beat and most arcade gamers never did. The character still managed to intimidate opponents 25 years later when a new Punch-Out!! was released for the Nintendo Wii.

Shigeru Miyamaoto, creator of the Mario Bros, the Legend of Zelda, Metroid and a slew of other franchises had actually designed the cast and started a tradition in for developers. He demonstrated through Mr. Sandman that a character designed with respect rather than trope would reflect back to gamers. In the very first blog of this series I mentioned that the developers that respected their subject matter often did better with audiences. Even if a fighting game pitted skeletons against cyborgs or revolved around dinosaurs the players could pick up whether or not the developer was simply trying to cash in on a trend or if they had really invested their efforts into the game and the universe they created. Kung-Fu master and Karate Champ were ported to multiple consoles yet neither received a proper sequel. By comparison the Punch-Out!! series was a hit in the arcade, on the 8-bit NES with an added plot, on the 16-bit Super Nintendo with new villains and years later on the Wii. The extra time, energy, diversity and attention to detail that Miyamoto and his team had put into their game clearly came across to audiences every time.

The Japanese did not think that creating caricatures of ethnic stereotypes or names would have caused a big fuss. Through the '80s not many people took notice. However when the Politically Correct / Ethnic Sensitivity movements took off in popularity the Westerners expected those in the business world to follow the trends. In Japan that was not the case. Again there was cultural relativism to consider. Of the two nations only the US had a major civil rights movement.

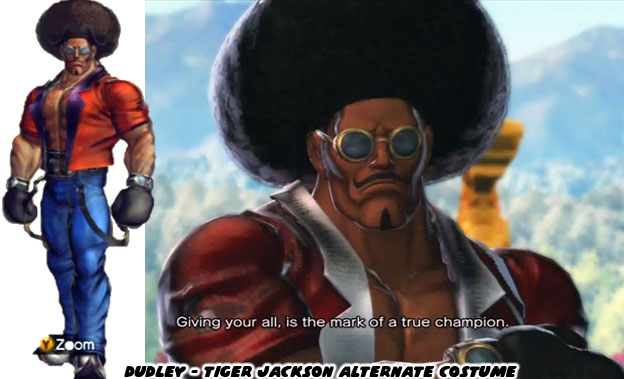

Capcom had created a great legacy of black boxers through the Street Fighter series, one of which played up the strengths and abilities of the sweet science rather than perpetuate stereotypical tropes. The bar that had been raised by the Street Fighter III team when they created Dudley was unfortunately lowered by the Street Fighter IV. More than a decade between games didn't make the Capcom artists any wiser. Dudley would receive an alternate costume of an afro and sunglasses modeled after the look of Tiger Jackson in Street Fighter X Tekken. He certainly didn't look very much like a world champ any more.

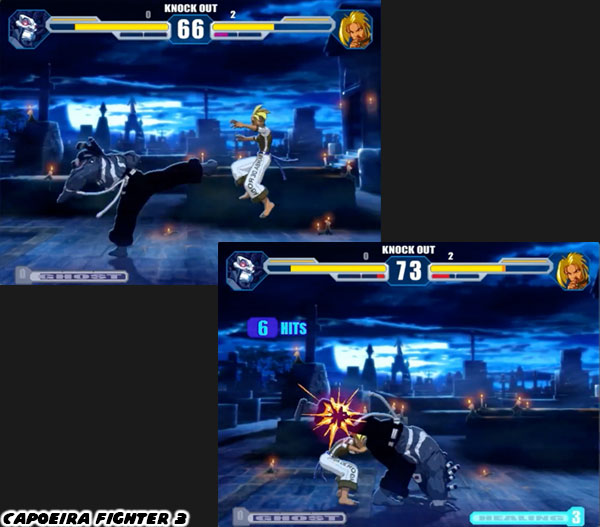

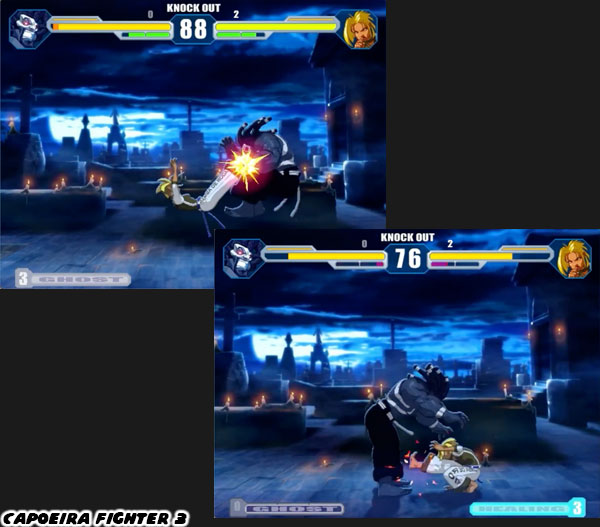

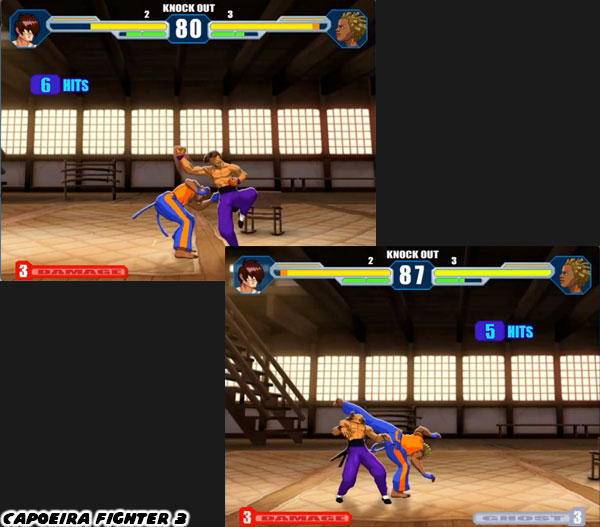

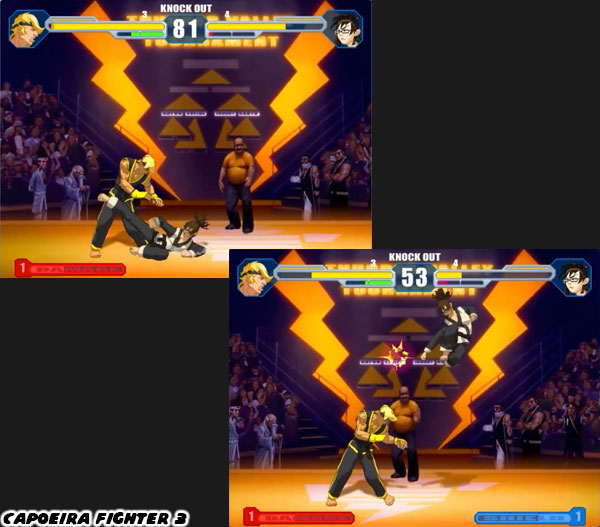

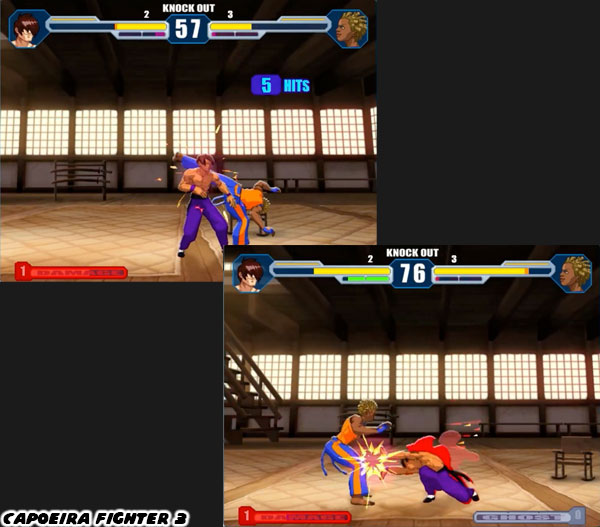

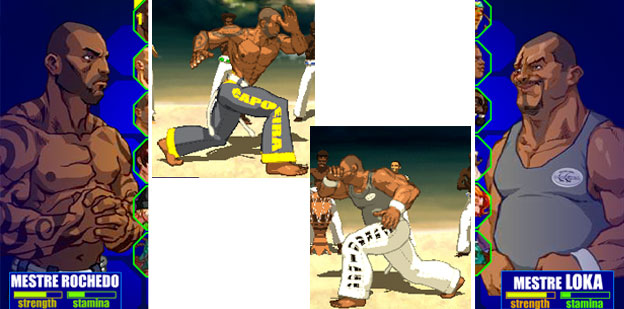

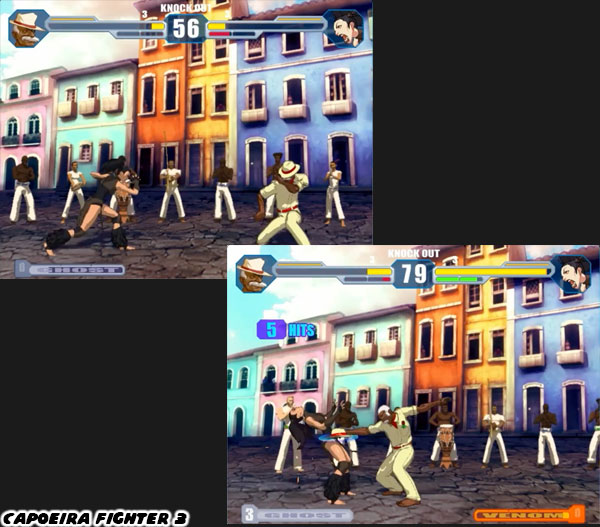

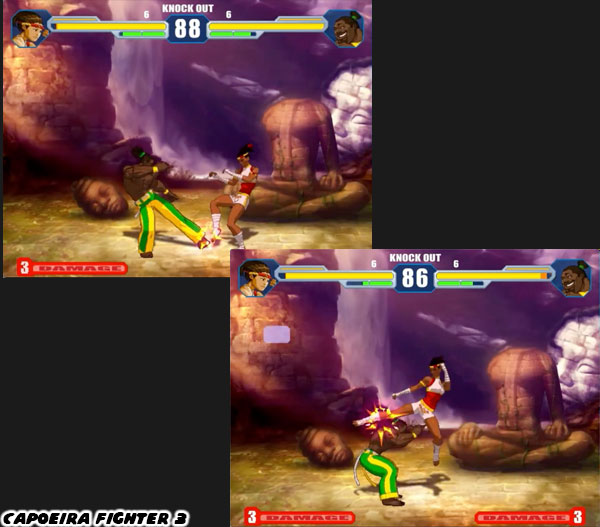

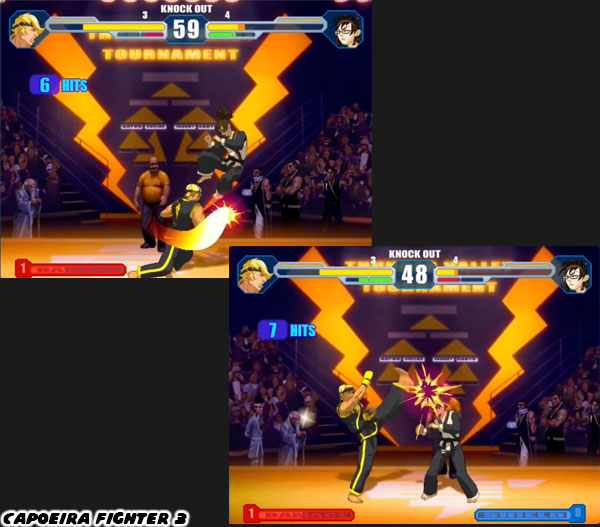

Developers in Japan and the US were stuck in a rut. Aside from professional boxers there wasn't much in terms of styles that they felt comfortable assigning black athletes. Basketball and breakdancing had become the new fad and by the mid-90s it was becoming tired to audiences. Thankfully Capcom and Namco wizened up and pointed to new fighting styles. Capoeira came into focus in 1997 thanks to Eddy Gordo and Elena. Even Sean was allowed to learn the assassin's fist that had been previously reserved for Ken and Ryu. Minority fighters suddenly no longer seemed locked into one role. A few years later Spiritonin expanded on that concept and began flipping conventions in their Capoeira Fighter series. Blacks, Whites, Latinos, men and women from different nations were all presented as exceptional capoeiristas. When those characters went on a wold tour they faced many new styles. These fighters from different nations also broke convention.

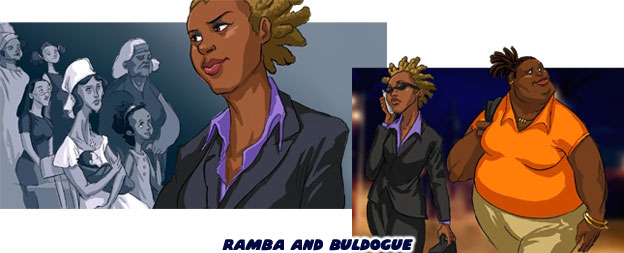

The boxing champion was a short British person with a Napoleon Complex. There was also a young Shaolin Monk, a German breakdancer, a female Tae KwonDo practitioner, a karateka based on the villain from the film the Karate Kid, a Scottish barroom fighter and a large Southern grappler. Rarely had any fighting game featured such diversity with regards to ethnicity, age and technique. Spiritonin had put the same level of detail on all the new fighters that they had with the capoeiristas. The moves each had, the special attacks, costumes, voices, names and even stages were built with forethought. The studio made sure to incorporate actual or appropriate details from each nation or culture to place on their cast. The name of the Shaolin Monk Kuan Yin Shen was based on a Buddhist deity. The young man spoke in wise passages during cut scenes, beguiling his age. Other characters had their own personalities on display while fighting or in their own cinemas.

The capoeiristas were joined by some other traditional and non-traditional faces. A Bruce Lee clone which all fighting games needed to have, a wild jungle girl, a female Muay Thai master (the first one ever featured in a fighting game!), a monkey kung-fu master (that I designed) and a couple of alien beings from the Guardians of Altarris (a different Spiritonin game) made a cameo appearance as well.

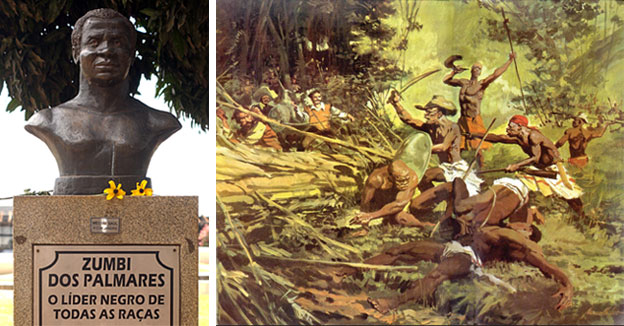

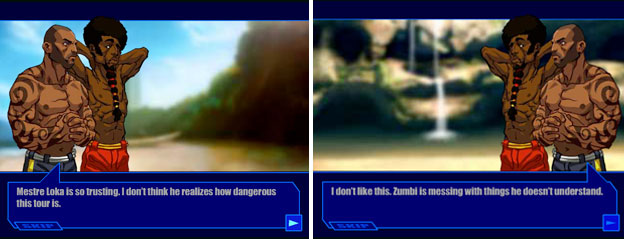

Spiritonin knew that a colorful cast was important but not as important as good control, great animations and a balanced fighting engine. They delivered on all those things while at the same time deconstructing the ideas of minority characters in fighting games. Women and blacks could not only make good supporting characters but they could also be important leading ones as well. The game had no set main characters although Meste Loka and Mestre Rochedo had been in the series the longest followed by their students. In order to make sure the game went beyond all expectations Spiritonin also wrote a new chapter in the book on villains. Zumbi Azul was so well done that I would rank him among the best villains ever created for a fighter. Zumbi was already an impressive bad guy but his dark alter-ego raised the bar. In all honesty I would rank Zumbi Azul in the top-5 bosses of all-time. He would even be in my personal top-3, second only to Gouki and ahead of Silber.

Spiritonin was able to insert powerful minorities and females into the genre as if they had always been there. They did not play the race card because they did not have to. They simply decided that it was finally time to bring fighting games into the 21st century. The biggest publishers in Japan and the US were taking too long to catch up with society. Spiritonin learned from Miyamoto and the other industry leaders. They treated their audience with respect. They placed men and women of color into a game without any pandering or gimmicks. The cast was balanced from a gameplay perspective but almost as important the members of both sexes had equal weight on the plot and outcome of the game. When Spiritonin wanted locations that meant something to Western players then they used actual landmarks. Even the fictional locations were still inspired by reality. The plantation mansions, the secluded beaches, the rain-forests and the colorful hotels featured in CF3 could be found sprinkled throughout South America. When Spiritonin wanted to create a convincing villain they used elements from ancient Afro-Caribbean and African-American spiritual customs that modern players could still identify. They did not put a costumed European in a corner and have him wave his hand to call down a meteor strike. In short the studio delivered something that audiences were not expecting.

An important chapter in the history of the fighting genre was written but for the web browsers instead of the arcade or home consoles. Capoeira Fighter 3 was a great game but did not get wide exposure. Because of this many "hardcore" and even casual players missed out. The biggest loser would be the entire industry. The big publishers on both sides of the Pacific would not learn how a fighting game should treat members of every ethnic group and culture. Nor would they learn that they could present attractive females that were also strong and athletic instead of just big boobs in skimpy costumes. Without a popular and successful template to work from most developers would rely on trope to design the next fighter. A generation that grew up seeing minorities and women portrayed in one way would never expect to see them in any other light. It was important that the developers get these impressions right the first time or else they would perpetuate stereotypes. It was simply not enough to live up to player expectations, the studios had to exceed them and redefine what the expectations should be. A great game and a terrible game could equally color their perception of gamers. The industry should always remember that the color of their audience should always be respected more than the color of their money.

Capoeira found its way into the world of mixed martial arts in the latter half of the 20th century. Almost a century ago the Japanese Count Kouma had demonstrated that jujitsu could be used to defeat the best capoeira striker. Suddenly the Brazilians felt inclined to begin studying this new form from the East. Yet as Kazushi Sakuraba demonstrated time and time again not even the Gracie jujitsu system was perfect. Many mixed martial arts fighters, not solely the Brazilians, took another look at the Dance of War and began adapting the sweeping kicks and unpredictable strikes into their technique. Now modern fighters are well rounded in the various fighting forms and are able to put on demonstrations that are as exciting to watch as any fighting videogame. Marcus Aurelio for example has an incredible sense of balance and makes capoeira look easy to do in a professional match as he takes out opponents with dizzying speed. While he may never achieve the legend of Mas Oyama we can see that the lessons of knowing multiple forms does indeed make one a better fighter.

I hope that you enjoyed this survey on the various fighting arts and how they migrated around the world. From the roots of grappling and kung fu that Indian monks took with them to China. To the merchants that crossed the Sea of Japan and introduced a continent to the Empty Hand techniques. there were the indigenous tribes in Indonesia and the isles in the South Pacific that kept their form alive as Dutch, Spanish and French imperialists sought to destroy them. When the fluid striking of the African arts crossed the Atlantic it mirrored the journey of millions of slaves. It would become wrapped up in ancient animism beliefs of the Old World and the crown of thorns from the New World. Its legacy would become the mix of Japanese blood in the form of judo and ju-jitsu. It would bear the illegitimate offspring of English catch-as-catch-can and US wrestling. These children would grow up on a steady diet of fighting. Their children and great grandchildren would continue to fight and shape the arts.