This did not mean that the characters were physically ugly but that they exploited the form simply for the sake of harming others. The worst of these offenders went by the name of Zumbi. The Mestre had played the heavy in the previous incarnations of the game but by the third chapter in the story he became a boss-level fighter. Zumbi did not simply gain a host of more powerful attacks but his voice, his appearance and even stage had changed dramatically. The end result was a monster of a man named Zumbi Azul. This new character observed many of the same conventions that were created by Capcom when the studio designed Gouki.

Capoeira Fighter 3 had a mix of influences, not solely from the fighting styles but also from other video games. It was heavily based in the visual style of Street Fighter Zero but with gameplay elements, control schemes and animations from Street Fighter III and Tekken as well. Part of the success of the other games were the memorable stages that the fights took place in. Spiritonin used landmarks that had a dual meaning in several of the levels. The Sao Paulo Cathedral and statue of Christ the Redeemer from Rio De Janeiro were important symbols from Brazilian Christianity. Two beautifully painted versions of these places, by Ford, were the backdrops for the heroic characters in the game.

The Western world was much better acquainted with the Christ figure and symbolism of churches and iconography. The themes explored by these stages would have been easily understood by Western audiences. Even non-Christians could appreciate the aesthetics of the level designs. The earth tones used for the cathedral balanced the cool darkness of the sky and the warm glow of a setting sun. It showed the beauty of the cathedral and the streets of Sao Paulo at night. The Christ statue itself was very serene and peaceful. The use of clouds made the stage location look heavenly. Those that followed the religion were familiar with the lessons of Christ. They knew that fighting was not a sin, especially not if the person was fighting against the forces of evil. In this case it would be the Christian belief versus the pagan ideal. Even the art of capoeira itself was filled with religious undercurrents. There was a sincere relationship between the Mestre and students, not unlike a priest or pastor and their parish. Those that would earn a name had to undergo a Batizado or Baptism as well and earn a place in the community.

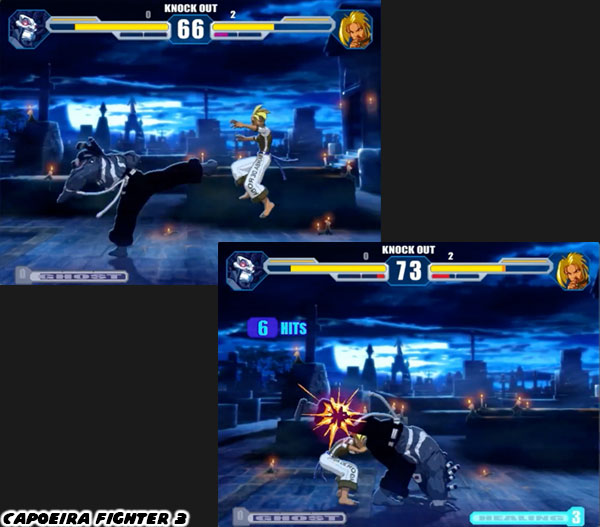

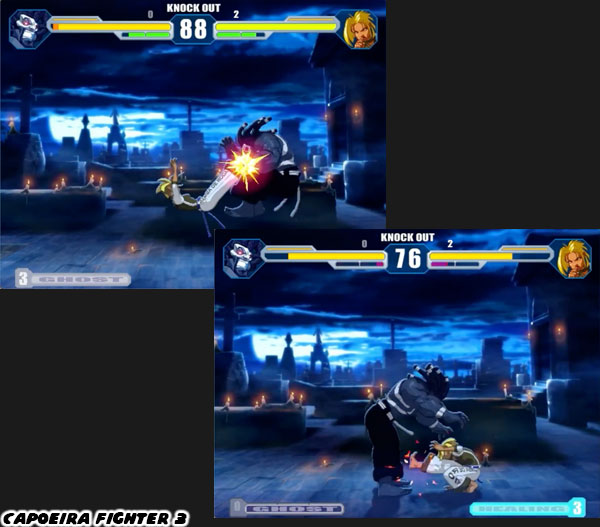

The cool blues and grays of an old cemetery at night were meant to elicit a chilly response from players. The full moon, framed by ominous clouds, gave off an ethereal glow. This type of level design was meant to tell a story. The stages created for Gouki in the Street Fighter series were layered with themes of Hell and the afterlife. Even though these places could have actually existed somewhere in Japan there was a certain subtext that was hard to ignore. The cemetery of Zumbi Azul was meant to do the same thing in Capoeira Fighter 3. This was the place that the dead called home. Any person foolish enough to face Zumbi Azul there would probably end up joining the residents before dawn.

This new "home" of Zumbi Azul was decorated with multiple candles, hinting that some sort of Macumba ceremony had been performed there. Of course popular media would suggest that the only types of ceremonies performed over a grave or mausoleum at night were unholy. If Zumbi had died physically, spiritually or even symbolically perhaps he would have been reborn with new powers. The spirits of the Macumba would now be in charge of the man. One interpretation of Zumbi Azul was that he had become a Zombie, or servant to the dark forces. The actual Haitian practice of Vodou gave rise to the zombie myth. Unscrupulous practitioners of the dark arts were called Bokor. These people would kidnap people to turn into mindless slaves. Other times they would raise the dead in order to turn them into servants.

The ceremonies the Bokor performed, their various potions, spells and curses had been closely guarded secrets for several centuries. Modern science had created a plausible theory for what these so-called masters of the dark arts had actually been doing. First they poisoned their victims with a strong neurotoxin, from a puffer fish or poisonous frog. This would slow down their breathing and heartbeat to an undetectable state. The person would then be declared dead and be buried in a shallow grave allowing time for the toxins to wear off. The Bokor would then magically "revive" the person by force feeding them a paste made up of sweet potato, cane sugar and the hallucinogenic plant datura. The end result, provided that the person actually survived the ordeal and was fit for work, was cruel and grotesque. The newly born zombie would be brain damaged from the lack of oxygen during paralysis and unable to communicate, reason or have any higher brain functions. The Bokor would constantly beat, berate and keep the zombie in a stupor with their drugs while forcing the zombie into a life of slavery.

The Bokor claimed that they did not raise zombies to sell into slavery but rather that these people were being punished for committing the most cardinal of sins against the religion. The lack of medical information and strong word of mouth gave credibility to the supernatural powers of the Bokor. It was not uncommon for some family members to remain vigil over the grave of a deceased relative until they were certain that the body had begun to decay and would not be exhumed. In other instances some people were dismembered by their own family before being buried. Whichever the case was the African and Afro-Caribbean communities learned to be wary of these mysterious rituals and practitioners.

The mythology of Macumba, the Orisha and Voodoo worked in favor of Zumbi Azul. This was a character that embraced his own evil tendencies and turned himself into a monster. It was as if he were both the Bokor and Zombie. He did not want or need an accomplice to perform the ritual he had studied up on. Those that wanted to follow in his footsteps, characters like Maestro and Buldogue, would be turned into blue-skinned servants. At least in one of the possible endings both of the fighters became minions for Zumbi Azul. This villain demonstrated all of the traditions that made for a great evil character. He was willing to do whatever it took to win. He lacked respect for the life of his opponents and even himself. He was willing to pay with his body and soul in order to achieve unstoppable power.

No comments:

Post a Comment