There was a reason why the designs used by the mid-90s were show quality. The robot figures in Virtual On were created by Hajime Katoki, he was a senior mecha designer on the Gundam series. It was a long time coming where robots in fighting games had as much planning put into their look and purpose as human characters had since the start of the industry. Sprites and sprite-based engines were how characters were represented in games through the '80s and early '90s. Robots in fighting games were rare at the start of the genre. The vast majority were usually cyborgs, humans with a few robotic enhancements. One of the first robot boss characters in a fighting game was named Ram-X. The character debuted in the 1993 Sega game Dark Edge. It was a unique title in that allowed a pseudo 360-degree playing field where sprites shrunk and grew to create the illusion that they were moving further back or closer to the player. Ram-X appeared like a Macross-style robot, one which could transform into a black fighter jet. It was a sub-boss character and non-playable. Audiences had a number of unique fighters they could play as, the characters Yeager and M.E.K. were cyborgs.

In the late '80s there was a big shift in technology. Arcade titles began to be developed on 3D engines. The earliest of which were racing titles because studios did not yet have hardware powerful enough to render convincing human shapes that could move and fight. That changed in the early '90s with the introduction of the Virtua Fighter and Tekken series by Sega and Namco respectively. In addition to being the first 3D fighters the two were notable for being some of the first to have android fighters. Androids were humanoid robots with artificial intelligence. The boss of Virtua Fighter was named Dural, she was a silver-skinned fighter that adapted to the moves of her opponents. Being a faceless, voiceless opponent made her intimidating. Of course the next android character was even more menacing. The enormous Jack appeared in every version of the Tekken series starting in 1994 and was "upgraded" on each new version. He looked like a bodybuilder-turned-soldier but underneath his plastic skin he was a robot. He could swing his arms like propellers, spin his torso 360 degrees and punch with the force of a cannon. If I didn't know better he was nothing more than a re-skinned version of the Mechanical Man that Mickey Mouse had build more than half a century earlier.

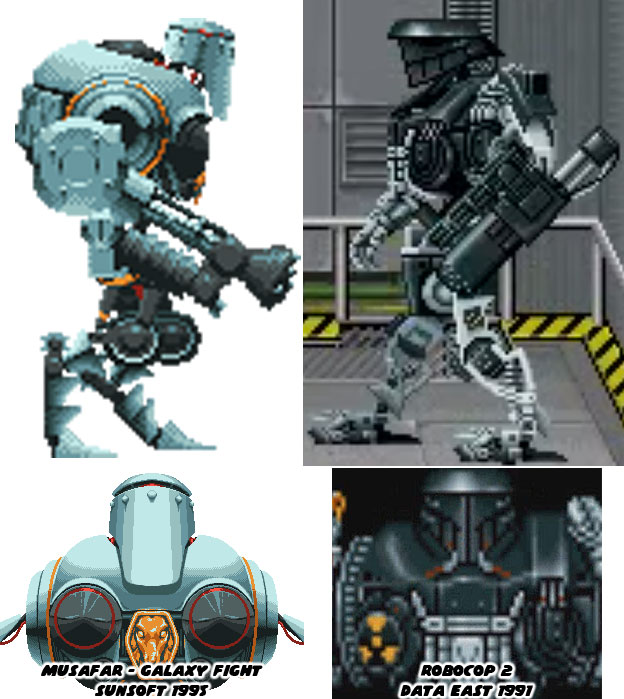

Namco kept the tradition of androids alive in the series through other characters like P-Jack, the prototype Jack and more recently Alisa Bosconovich in 2009's Tekken 6: Bloodline Rebellion. Alisa is very similar to Astro Boy in that she has a number of weapons hidden underneath her artificial skin. She also mirrors Astro in that she was created to be a surrogate child for a professor, in this case it was Professor Gepetto Bosconovich. Of course anybody familiar with the story of Pinocchio recognizes the name of her creator. The Japanese were fond of borrowing from pop culture while designing their games. When it came to putting robots in fighters they could design based on the trends or they could outright poach the look of a character. The second option was used in Galaxy Fight. The robot Musafar was actually the head and brain of a human encased in the body of a robot. His design and attacks were modeled after Robocop 2, the villain in the movie and game of the same name. Robocop 2 was a game made by Data East a few years prior.

The 1995 title by Sunsoft was set in the far future and was one of the first to focus on human versus alien combat. Galaxy Fight had a diverse cast and featured a typical plot of the humans and aliens uniting to defeat a powerful alien bent on galactic domination. Despite the serious tone and history of some characters the game was interjected with some humor. Some of the characters in the game appeared a year later in a more comedic fighter called Waku Waku 7. What was interesting about the robots featured in gaming, not just from Japan, were how many cues they took from pop culture. Musafar was just one example but the influences did not stop there. I had mentioned previously the 1995 game Cyberbots: Full Metal Madness. The game by Capcom had some very unique designs. The influences from pop culture were subtle and instead the artists at Capcom, including Kinu Nishimura and Daigo Ikeno got a chance to work on original mecha ideas. The biggest poach of the game was Zero Gouki, but he did not appear until the game was adapted for consoles.

A few years later Capcom would go into full fanboy mode and release their first and only 3D fighting game featuring giant robots. The 1998 title Tech Romancer was an homage to the various giant robot shows over the past 40 years. There was at least one robot in the show that represented every type of giant robot anime that the producers had grown up with. Whether it was a silly kids show or a space drama for teens, from the Transformers to Macross and everything in between there was a robot that reminded audiences of 40+ years of anime. Capcom did a good job of changing just enough details so that they couldn't be accused of plagiarism. Also unlike Sega's Virtual On the combat for these robots was closer to a traditional fighting game than a 3D simulator.

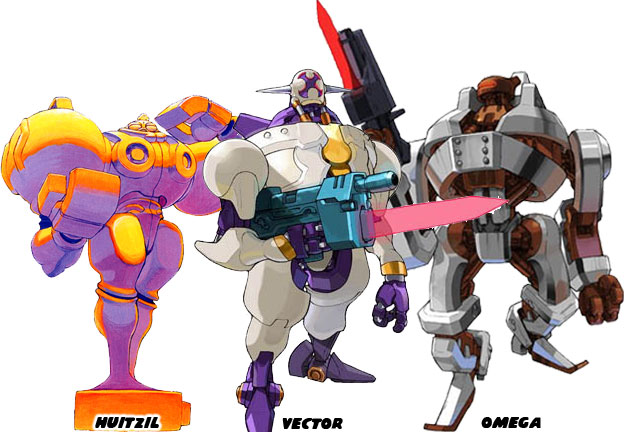

Capcom had a history of making some memorable robotic fighters. Some of their best work had nothing to do with piloted mecha. As early as 1994 the studio had started a trend that they would follow through the rest of the decade. The game Darkstalkers, Vampire in Japan, introduced the world to Hutzil. It was actually an ancient robot that was modeled after the clay Dogu statues by the Jomon people, the neolithic ancestors in Japan. Huitzil could change shape and had a number of weapons hidden throughout its forms. From the ancient robot to the futuristic Capcom next explored fighting robots in the game Star Gladiator in 1996 and its sequel Plasma Sword: Nightmare of Bilstein in 1998. Both of those titles were done on 3D engines. The robots Vector and Omega fought similarly. They could spin, twist and shoot their machine guns as well as internal lasers. The Star Gladiator series was a sort of fighting game homage to Star Wars with the exception that the robots in this game were not comedic sidekicks.

Around this time the west was experimenting with different types of fighting games as well. Since CGI graphics were relatively new they stood out when compared to the hand-drawn sprites that made up 99% of fighting games. Going with computer-generated models was part of the appeal of the original Killer Instinct. One of the first, if not the first, all-robot fighting game was Rise of the Robots. The 1994 game by Mirage was considered one of the worst fighting games ever released. The studio focused its efforts on a diverse cast of robots and highly-detailed backgrounds. What the studio forgot to do was focus on the gameplay, animation and balance. Those three things pretty much determined a hit or miss in the community. Despite the cool looking robots the game played like a slug. Also the publisher failed to recognize that neither the consoles nor the home computer was powerful enough to render the complex models and stages in real time. When the game was released it was mostly pre-rendered backgrounds and sprites.

Rise of the Robots, just like many fighting games that came before and after, failed to live up to the hype. How would a new western effort like Rising Thunder be any different? Well first off it was any indy game and had no connection to a major publisher. The game was also a free-to-play online title. As far as the gameplay went it was being balanced thanks to the feedback of the fighting game community. These were just a few things that Rising Thunder had in its favor. The next blog will look at the stars of the game and wrap up this series. I hope to see you back for that! As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

Imo a nice example of robot-like fight game was "zero divide" published on PS1 and PC by Zoom in 1995.

ReplyDeleteIt was a Virtua Fighter clone with a cyberspace setting.

The characters were some sort of cyber avatars of the player and the 1P and 2P versions were differentiated being the 1P (default) version more polished than the 2P, sort of 1.0 and 2.0 software versions.

http://www.zoom-inc.co.jp/ps/zd/web/chara_zd.html