For the next portion of this series I would like to take an extended look at how one fighting art was tied into the history and culture of the slave trade. To mention the fighting art and separate it from its racial origins would be a disservice to the practitioners. This series will cover some sensitive topics so if you do not want to read about minority figures in fighting games then please return at the end of this series. In previous blogs I had mentioned that the Japanese had become almost notorious for perpetuating certain takes on African-American culture. No where else was this more apparent than in fighting games.

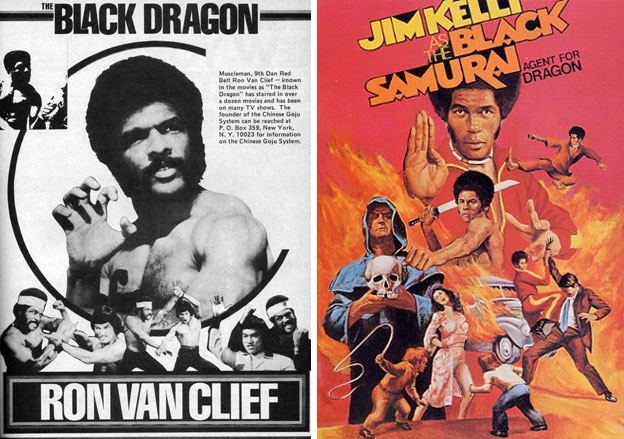

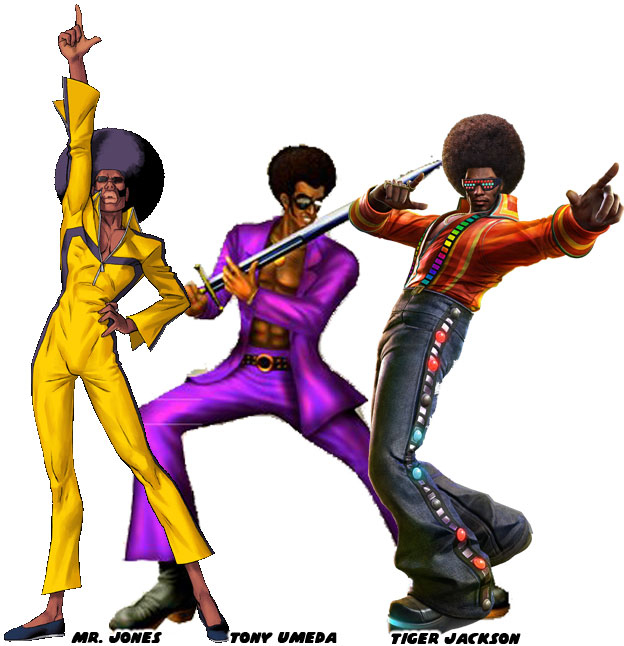

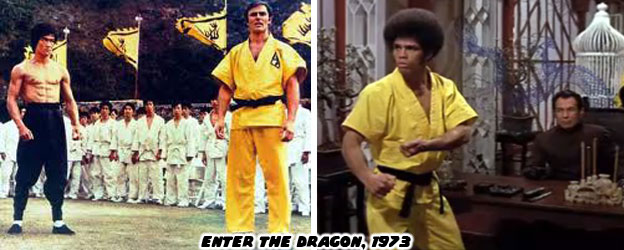

The flamboyant afro-sporting black man had become a gaming trope. Look at Tiger Jackson a hidden character in Tekken 3. The Namco title from 1997 was one of the first 3D games to exploit this dated character concept. A year later Square released Tony Umeda in their sword fighting game Bushido Blade 2. He was a mixed ancestry character being half-Black and half-Japanese. Of course that didn't explain his costume. Bell bottoms, platform shoes and afros had fallen out of favor at the end of the '70s. Years later it would return in arcade titles. Tiger Jackson and Tony Umeda was followed by Mr. Jones / Jones Damon from Rage of Dragons. Both characters were undoubtedly influenced on the classic Jim Kelly character Black Belt Jones as well as the "Black Dragon" Ron Van Cief. Black fighters created by Japanese developers seemed incapable of escaping the look. Even Zack from the Dead or Alive series became an afro wearing clown at one point in the series. Believe it or not Mr. Jones was considerably worse.

The 2002 game by Evoga was set in the Double Dragon universe. The game actually had a pedigree. It was a descendant of what many consider to be the original arcade brawler. Double Dragon was held in high regards by long-time arcade players. Sadly the fighting games based on the franchise were lackluster. They demonstrated a lack of originality and innovation. Evoga was borrowing gameplay elements from titles like the King of Fighters and even graphic styles from Street Fighter Zero / Alpha. Copying rival studios and introducing characters like Mr. Jones into the genre just about guaranteed that it would be forgotten by audiences. The studio ended up doing a disservice to those long-time players by failing to respect the legacy they were drawing from. Things had been slowly devolving for the genre before Rage of Dragons had even been released. The mid '90s gave game players reason to believe that the Japanese did not know their audience as well as they should have. At best they were just filling a niche but at worst they were negatively coloring the perception of audiences.

Not every character that came from a Japanese artist was done so out of willful ignorance. Afro Samurai was written and drawn by Takashi Okazaki and published in manga form in 1999. It would be serialized and even adapted into an animated mini-series and game a few years later. The creator was actually a huge fan of Hip Hop culture, the music, the fashion and the movement. He saw his titular character as an homage to the super-cool characters Ron Van Cief and Jim Kelly had played in the "Blacksploitation" films all those years earlier. What was unique about the martial arts films that the black actors were cast in was it was the first time they were allowed to be the stars of the films. As long as they could fight and act they were invited again and again. The films even had the occasional relationships with Asian women on screen. The studios in China and Taiwan had a much more progressive attitude towards blacks than the US had. It was no surprise why Van Clief chose to work there when his own country didn't welcome blacks.

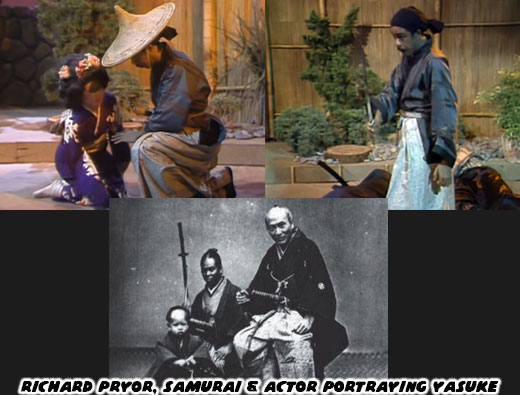

The first black samurai character in pop culture appeared in 1977, around the height of the Blacksploitation movement. This character, who mumbled in fake Japanese, was portrayed by Richard Pryor on his short lived comedy show. There had been an actual historical precedence set for this character however, his name was Yasuke and he first appeared in the 16th century. Yasuke was the first and only recorded black samurai from feudal-era Japan. His name was actually given to him by the warlord Oda Nobunaga. While this person is not really known about in the west the Japanese would have recognized the archetype. It was what allowed characters like Tony Umneda and the Afro Samurai to be accepted.

Some artists working on the black sword master didn't quite grasp the subtleties that Mr. Okazaki was going after. His work was bold, violent, stylish and very avant-garde. The things that made the Afro Samurai popular in manga and animation circles was lost on many other Japanese designers. To many artists and consumers black people were gimmick characters. They could never really carry a series. In 2008 SNK introduced the first black character in their popular Samurai Spirits / Shodown series. J. was a sailor that was shipwrecked on Japan. He learned the art of sword fighting, he nicknamed his sword Elvis (I'm sure the designers thought they were being clever) and he became a hired swordsman. Most people were scared of his skin color more than his fighting ability. They called him the "Black Devil." To make him more empathetic to Asian audiences his goal in the game was to free a geisha that had shown him kindness and wasn't scared of his color. Japan had been on the wrong side of black character design for years but were beginning to give them more dimension. Only time would tell if the trend would continue. Things weren't really much better on the other side of the ocean.

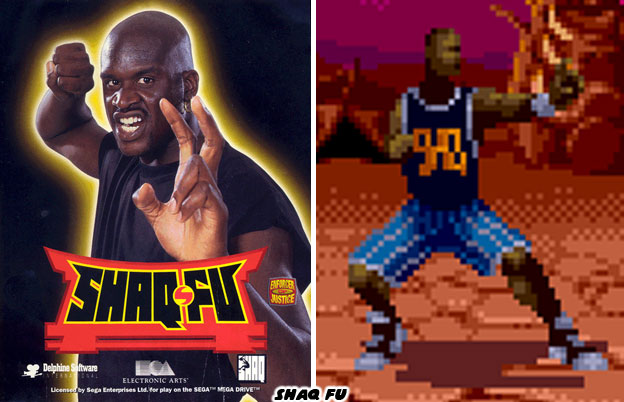

The United States Congress had gone out of their way to interpret every corruptible influence they could from fighting, action and shooting games through the '90s. They tried blaming violence in video games as having a detrimental affect to children and society as a whole. It was a similar argument that they had about comic books and rock and roll music a few generations earlier. In the end these accusations were baseless but ended up in the music, comic book and video game industries creating a form of self censorship. Some things that was never addressed in the Congressional hearings and something that the gaming industry and the gaming media managed to ignore were the subtle racial undertones placed on characters. Violence was one thing but racial bias was apparently something too taboo to bring up. Things were especially bad for Black characters in 1994. They were not always African-American but when they were they could be guaranteed to share similar traits. Magic Dunker was just one character in a series of black, basketball playing, fighting game characters. It was not hard to tell who the token "American" character was in the game given his Star-Spangled costume. He originally appeared in the game Fight Fever by Viccom. Apparently the Japanese had been keeping up with trends. Magic Dunker and the other black fighting game characters appeared the same year that western publishers had released the dismal Shaq Fu, a fighting game featuring Shaquille O'neal the master of "Shaquido." Japanese developers were giving audiences what they assumed they wanted.

In reality the developers in Japan had mainly pop culture as a point of reference for the USA. When they wanted to make a character that would be popular with the Americans they looked at the trends. The biggest stars in the US seemed to be music stars and sport icons, at least according to television. Singers in general did not have the physical traits of a fighter but athletes were spot on. Magic Dunker had the stylings of Magic Johnson and Michael Jordan, two of the biggest stars of the era. The hi-top sneakers, flat top haircut, tank top and sweat bands were slightly behind the fashion curve though. Perhaps the Japanese were working from dated information. The athlete-as-a-fighter carried over several times on other titles.

Shaq and Magic Dunker were joined by Bobby "Brown Bullet" Nelson. The breakdancer and basketball playing prodigy from Aggressors of Dark Kombat was one of the youngest fighters ever devised. The SNK title was developed by Alpha Denshi Corp. and there was little originality in his basketball-based and dancing attacks. Not that Lucky Glauber from the King of Fighters USA team was any better but at least he was an adult. Glauber did not have any named style of fighting but instead relied on his long legs for sweeping kicks and basketballs he could summon out of thin air to throw at opponents. At least fighters of other nationalities or ethnicities were allowed to have more convincing fighting styles. The Neo Geo arcade cabinet seemed to be a magnet for these ill-advised characters. A few years later Capcom introduced Sean in Street Fighter III. The game from 1997 did not force the character to have either dancing or basketball-based attacks but the studio did incorporate basketballs into his opening animations and taunts. It was unsettling how similar the fighters were, what traits they shared in common and how little the Japanese seemed to know about black culture, at least about blacks in the USA.

If gamers were offended by these characters, not that they were necessarily, it was because the Japanese were holding up a mirror to Western society. What the developers had learned and assumed about the US was pulled from media from the West. The biggest icons for black culture were featured in Nike ads and McDonalds campaigns, ten times out of ten they were athletes. The news did little to help the image of blacks as well. A person watching television that didn't speak English would see a black criminal, entertainer or sports star, sometimes all three were the same person, within the span of an hour. Was fame the most important thing a black person could strive for? The positive role models in science, politics or education were not as visual or as celebrated on television. This perception skewed the view that the world and not just Japan had about Americans. For African-Americans it was more divisive. Some of the cultural cues that were being picked up by developers were insensitive to the black community and actually reinforcing stereotypes. Basketball was one thing to pin on the fighting characters but it soon became more subversive than that.

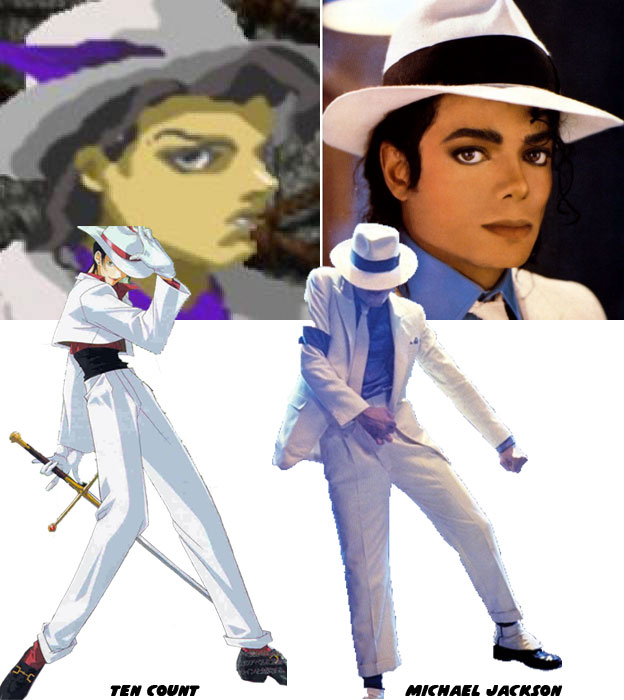

In 1997 Takara released the third part in their 3D weapon-based fighting game. Battle Arena Toshinden 3 introduced a character that danced, did a high pitched yell and moonwalked with a saber in hand. His name was Ten Count. The similarities between himself and the legendary performer Michael Jackson were too much to ignore. It was a shame too because the series was a ground breaker. It was the first notable 3D weapon-based arcade fighting series. It came out in the middle of 1995. The more popular Soul Edge, the first in the Soul series by Namco, didn't debut until the end of the year. While Ten Count was a blatant rip-off character the other black fighters from the '90s didn't fare much better.

Boggy, a character from Kaiser Knuckle, made his debut in 1994. The game by Taito was one of the worst fighting games developed. It gave Fight Fever and Aggressors of Dark Kombat a run for their money. Boggy was an entertainer and a fighting man at that. Apparently the Japanese developers were a bit behind the times when they introduced the breakdancing brawler to audiences. His look, clothing and mannerisms were all dated. His fighting stances were not from any named fighting art but mostly made up of dance steps. Where else could these influences have been pulled from than from television, specifically music videos? Were the developers really so detached from Western audiences as to only use second-hand sources for inspiration or did they assume that these characters were appropriate?

An important thing to consider was cultural relativism. The reaction to Boggy, Magic Dunker, Bobby Nelson and the rest was different outside of the US. Other countries might have had the same ideas about black characters based on the same television shows and movies they saw from the West. For all they knew these things were true of all black people. The view that the global television audience had was broken from the get-go. Reality rather than sensationalism was seldom shown on television. Poor, rich and middle class blacks existed but were never covered by the news. Their stories had not been shown on sitcoms or dramas. At leas not since the '80s. To the developers overseas it was okay to have dancing, basketball playing black people in fighting games. Minority characters in fighting games appeared as marginalized as they had been in society. Very few countries ever had the minority groups push for change at the local, state and national level in the way the Civil Rights Movement had in the USA. Even today stereotypes, racist attitudes and institutionalized segregation were very real issues the world over. There were not laws against discrimination in all of the nations. Minorities and women could be denied benefits, rights and privileges because their employers and even government were immune to reprisal. The characters that debuted in 1994 skirted the sensibilities of Western audiences, they were borderline racial caricatures that harkened to a dark era in US history. The next blog will look at the fine line that the Japanese developers walked during the fighting game boom. As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

Another gem Noe! I had no idea that "Yasuke" existed. Keep these bad boys coming!

ReplyDelete