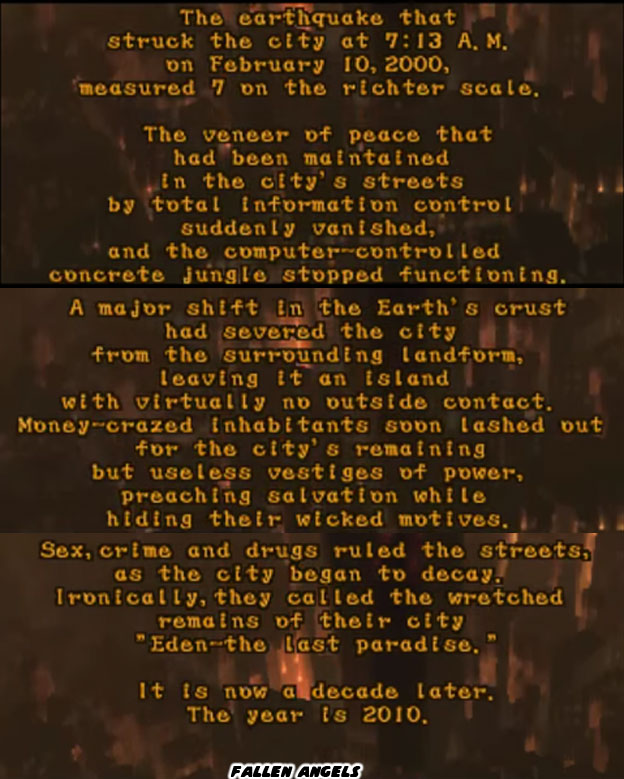

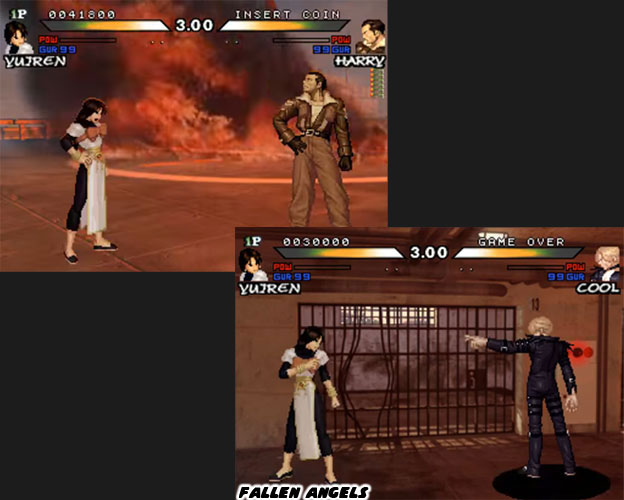

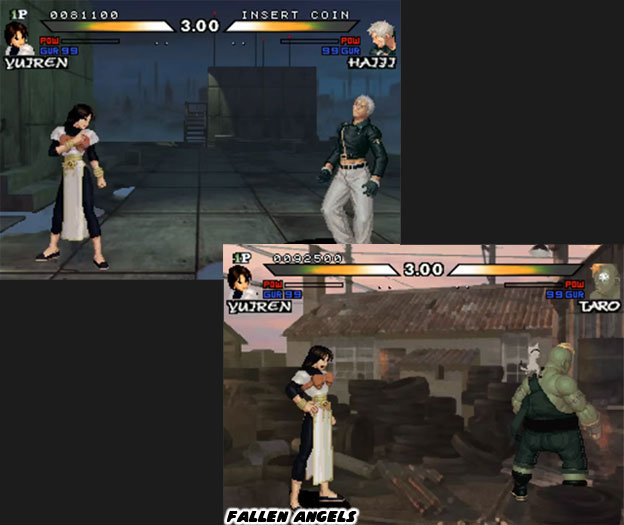

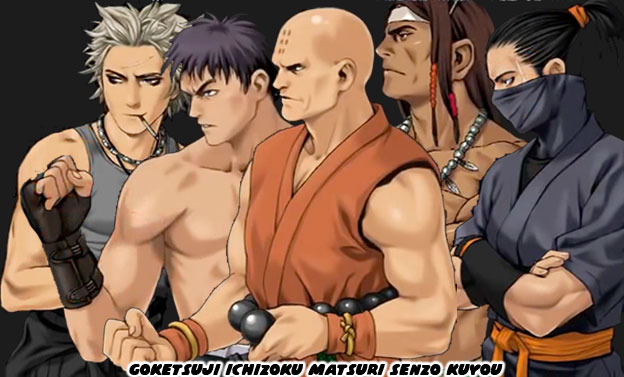

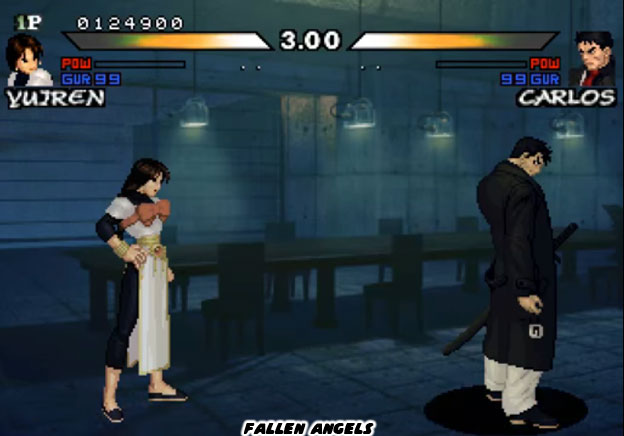

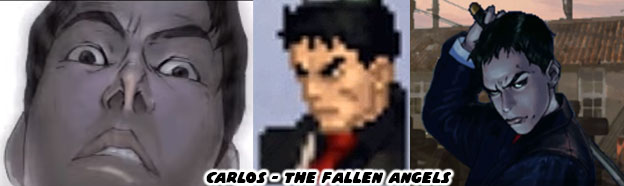

A crime boss by the name of Carlos was pushing all the other mobsters out of power. He wanted to rule the island nation of Eden. This enraged other crime bosses and gangs. But in a world that was cut off from emergency services and even law enforcement this meant that only those that could fight had power. To increase his dominance Carlos began assassinating his rivals. During the events of The Fallen Angels he had heard that there were some dangerous people trying to hunt him down. That was when he called in his right hand man. This person was very stylish, he wore a red suit and dark sunglasses. He was called Trigger and acted as the sub-boss in the game. Trigger was the type of character that could drive a fighting game player mad. He did not use any style of martial arts, instead he fought with a pair of revolvers. They were equally deadly at distance and up close. Also, unlike other fighting games where a bullet was easy to track or evade, in this game every gun shot was near instantaneous. The words cheap and overpowered often came into play when talking about fighting game balance. Yet at the same time Trigger made sense in the context of the game. This was not a tournament, this game was about vigilante justice. There were no rules saying that people could not use weapons in a fight. If audiences were able to get past Trigger then they faced off against the final boss in a darkened board room.

Carlos was tall, almost the tallest character in game. His strength and range were already above average but then Steel Hearts gave him a weapon as well. Carlos fought with a katana aka samurai sword. It didn't matter what type of form the heroes practiced. Just a few slashes with a sword could kill them. In a traditional fighting game this was cheap but in the Fallen Angels it made sense. Think about it for a moment; if this were an action movie, or action game, then audiences wouldn't have complained that a boss character not fighting fair. Bad guys in films always fought dirty and did things that the heroes couldn't. In the end, depending on which character was selected, a single line explained why each person was fighting. Some did it to get a fresh new start in Eden. Some did it to bring justice to the city. Others did it to save themselves. And some did it just for the sake of taking over. Steel Hearts did not get a chance to create any proper ending cinemas for the cast. Nor were they allowed to create any sort of in-depth level intros. Who knows how far the story would have gone and what the fallout would have been. Maybe the game would have had a sequel or maybe it was designed to be a self-contained adventure.

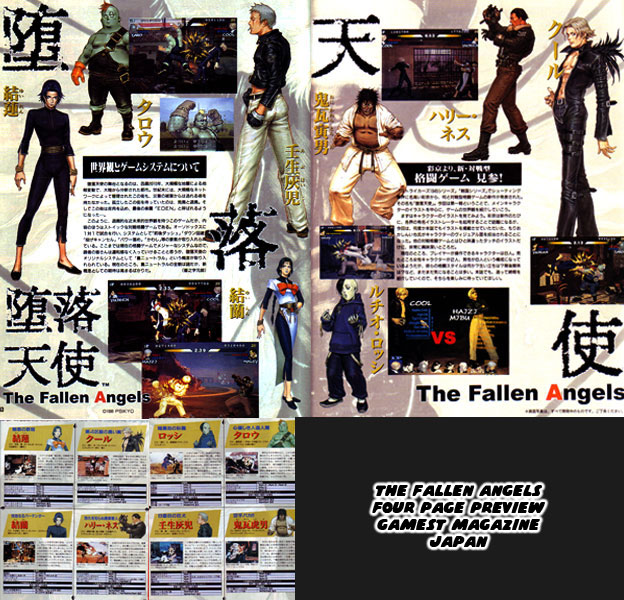

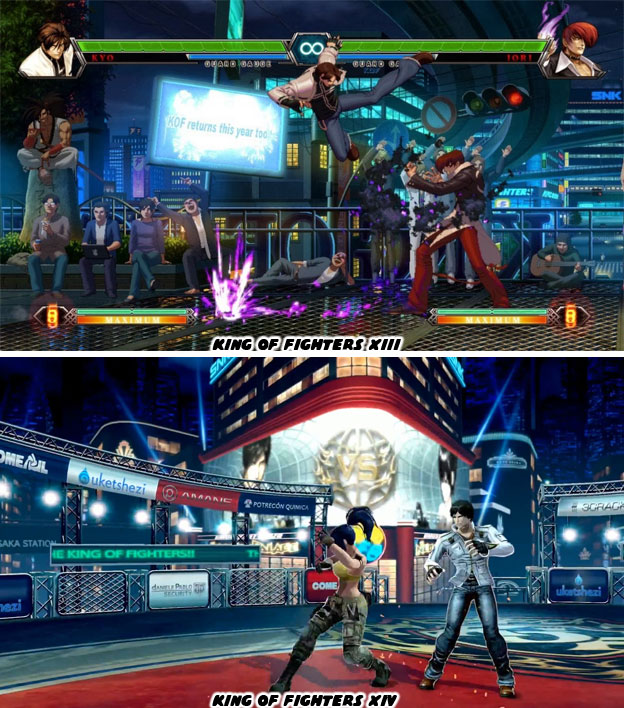

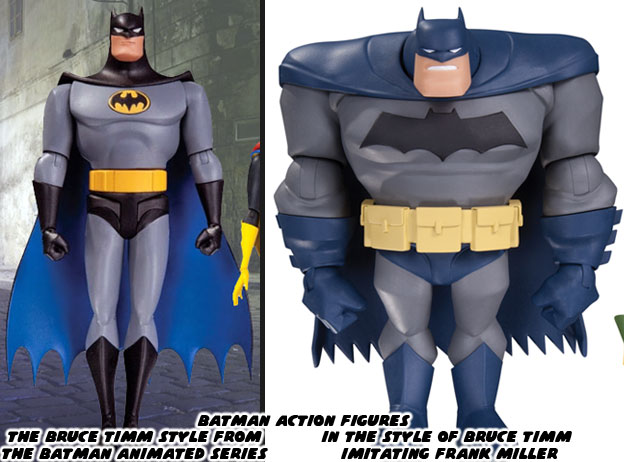

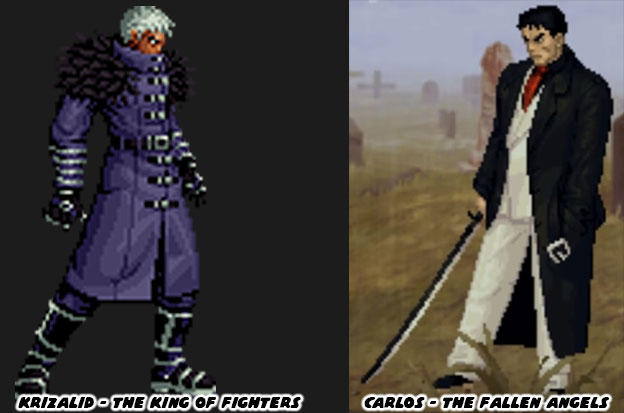

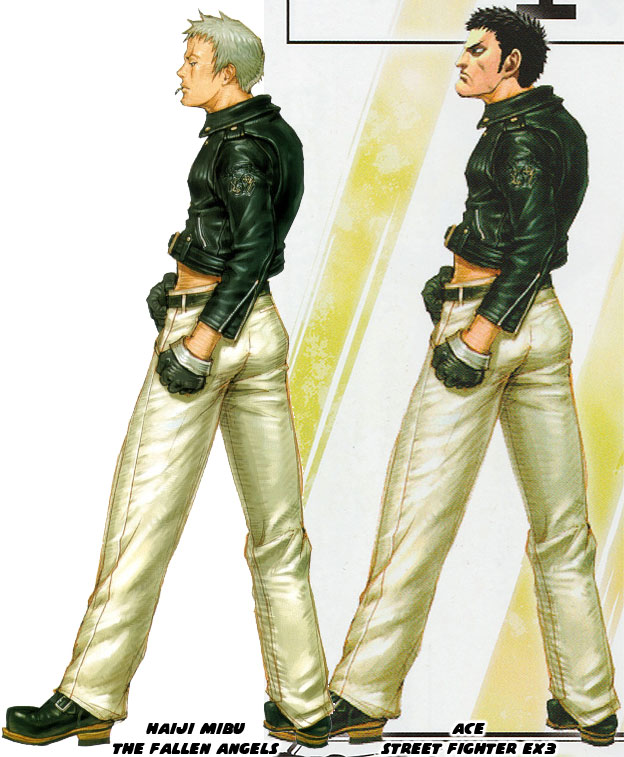

The developers had planned on shaping a bigger experience than what was presented. The incomplete story, unfinished sprites and other data found in the game ROM could attest to that. No other developer followed in their footsteps. The lesson was learned, creating a game with an incredibly strong aesthetic, a unique visual style and presentation would cost too much money and take too much time to be worth it for any publisher. The influence of Steel Hearts, the importance of what the studio was trying to deliver however did not stop with the Fallen Angels. Director and co-designer Mitsuo Kodama, along with artist Toshiyuki Kotani aka Styleos, went to work at SNK. One of the first things they did was change the direction of the King of Fighters franchise. They introduced some new lead characters and villains. Eagle-eyed fans noticed that the new characters in KOF '99 looked eerily similar to the characters in The Fallen Angels. the French website GangGeekStyle did a great writeup and compared the Fallen Angels to the KOF characters that evolved from them. Remember that the team also went on to work on The King of Fighters '00 and The King of Fighters '01. Around this time SNK was in bad financial straights and underwent bankruptcy, I wonder if the change in direction had anything to do with it. The KOF 2001 and 2002 were actually developed by the South Korean studio Eolith. The comparisons between the white-haired antagonists in the KOF series, K' and Krizalid and the metrosexual anti-heroes in the Fallen Angels Haiji Mibu and Cool should be obvious. Also the trademark attacks for both Maxima and Harry Ness were rockets in the sleeves of their jacket. The major difference being that Maxima was a tall cyborg and Harry was a big soldier. Yet the idea of a villain in a long coat was nothing new in SNK fighting games, See Rugal, Goenitz, Mr. Big, etc. Both Krizalid and Carlos fit the mold as well.

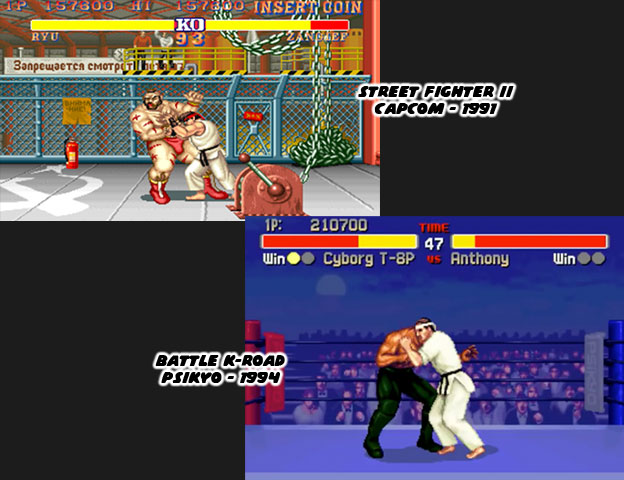

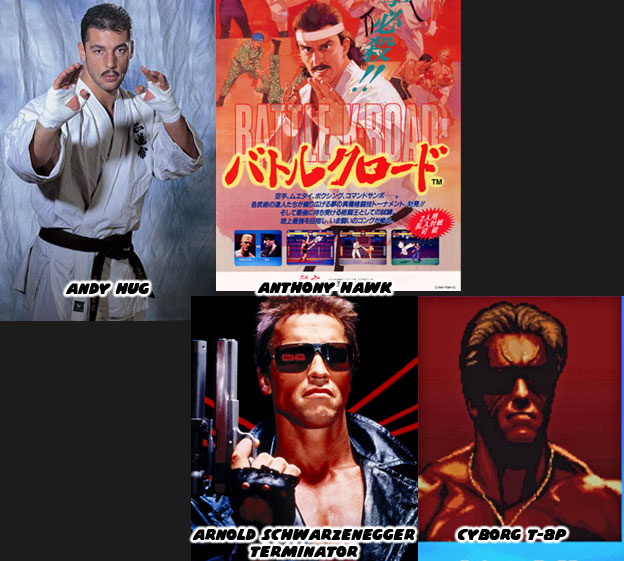

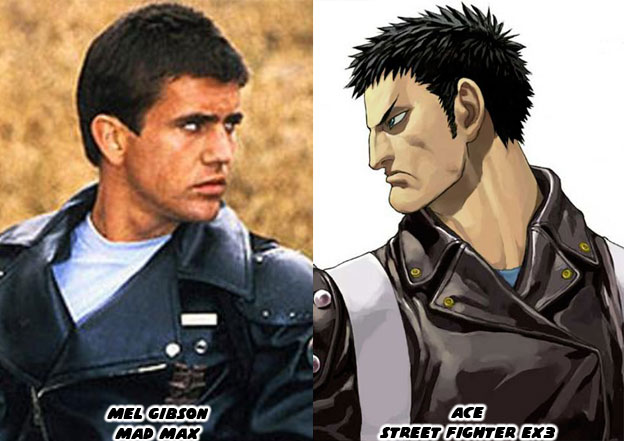

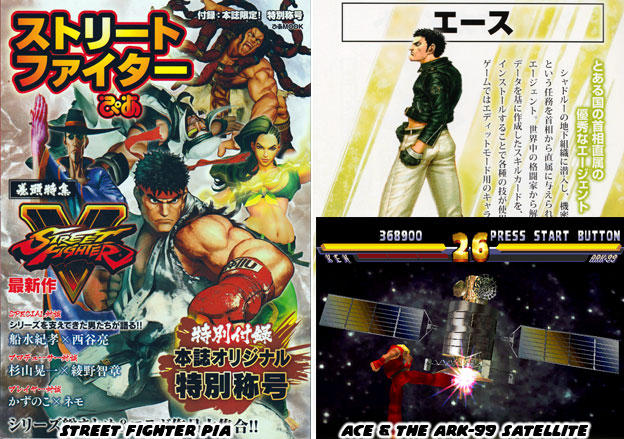

SNK had made changes to their franchise very quickly. They didn't try to recreate the aesthetic from the Fallen Angels, the mood of the levels, or even the large detailed sprites. That would have held up the development of the King of Fighter series for a few years and put them way over budget. The decision to pursue Dot Art graphics, detailed high-resolution sprites, eventually happened. It may have been influenced by what Steel Hearts was trying to achieve. But that was not the only interesting thing that happened following the debut of The Fallen Angels. In 2000 ARIKA released Street Fighter EX3. This was the first fighting game that the studio had released after Fighting Layer in the arcade in 1998. ARIKA had made waves with the fighting game community because Fighting Layer was published by Namco but it featured two characters from the Street Fighter EX series, Blair Dame and Allen Snider. Neither of which appeared in Street Fighter EX3. In their place was a new character named Ace. Movie fans noticed how much this new character appeared like Max Rockatansky from the Mad Max films. He had the same angular haircut and the same armored jacket with only his pants being a different color. In the canon of the series Ace was the next evolutionary step from the Cycloid program. These were cyborgs that could copy the moves of any fighter.

Ace ended up having a few of the moves of Blair and Allen at his disposal. Some people wondered if he had crossed paths with the former EX stars. Did he beat them in combat? Did he arrest them? Is he a clone? ARIKA wasn't saying anything official about the events or canon of this game or Fighting Layer. Leaving audiences to speculate about what happened. It didn't help that ARIKA would tease the characters in their infamous April Fool pranks. Credited in Street Fighter EX3 were producer Tatsuya Minami and co-designer: Hiroshi Okuda, Kiminori Tsubouchi. None of the senior people had worked on The Fallen Angels, at least none that I saw in the credits had any involvement with The Fallen Angels. But here is where things get very interesting. For many years some people in the fighting game community thought there was something oddly familiar about Ace. I think his look was partially inspired by Carlos from The Fallen Angels. The sharp hair, and dark coat being the most obvious similarities. But it turned out that there was much more to it than that.

For more than a decade I looked high and low for official art from Capcom or ARIKA on Ace. I got just about every art book Capcom had ever released and even a few of the ones that Udon translated from Japanese. There was nothing outside of the character profile that we had already seen. That was until the Street Fighter PIA Mook (magazine/book) was released in 2016. The paperback talked about every character and game released in the series up until Street Fighter V. F.A.N.G. was at that time the newest character. The book also mentioned every crossover that the series had with other franchises, including the costumes in Monster Hunter, and Dragons Dogma. The reason that I bought the book was because it inlcuded all of the Street Fighter EX characters as well. The most obscure being ARK-99, a satellite that players could beat up in the bonus stage of Street Fighter EX2. The second-most obscure character was Ace and that was when I got a clear shot confirming my suspicions. I bought the issue so that I would always have proof that the character was canon and the art was either stolen or never credited correctly.

The character art for Ace was poached from the original illustration of Haiji Mibu from The Fallen Angels. I don't mean that they were similar poses, similar costumes or similar color choices. I mean that the studio took the original head off of the character and replaced it with Ace. If the artist that did this was anybody but Morioka Shinichi then it would be art theft. It is possible that Mr. Shinichi went with an alias in the credits. But if so I have to wonder who at ARIKA thought that this would be a good idea. The Fallen Angels may not have been widely received but the characters were so unique that they were hard to miss. When I got the Street Fighter PIA the first thing I did was scan the full body picture of Ace and then track down my copy of Games Mook Vol. 113: Psikyo Illustrations. I scanned in the Haiji Mibu piece and put them side-by-side. There was no mistaking the illustration now. The suspicions that Street Fighter fans had was confirmed. Audiences had seen this character before, and for some they had seen the design used twice in both an SNK and Psikyo game. I have yet to find a Japanese article or site that would explain why the recycled art was used.

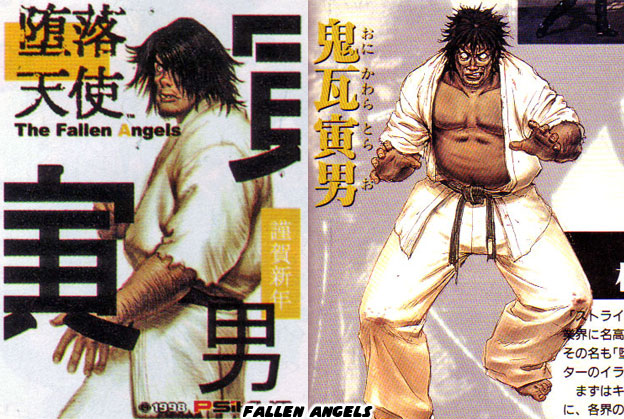

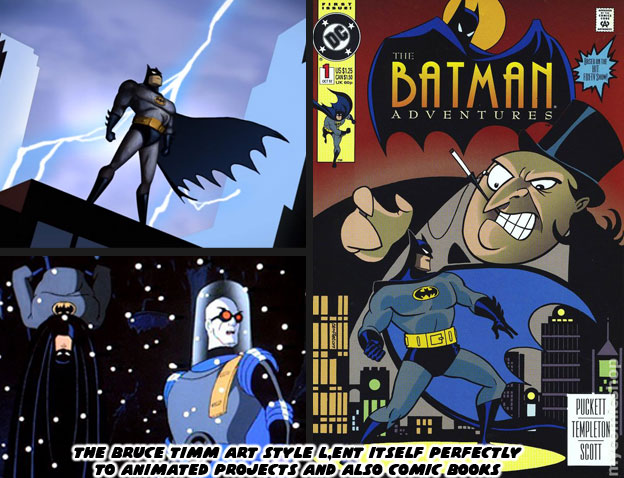

The Fallen Angels was an example of what would happen if a developer decided to pour all of their resources into a game with an uncompromising aesthetic. They transcended the argument of what good graphics look like because no other studio could compare to what they achieved. Aside from being beautiful to look at The Fallen Angels introduced new ideas into the genre. Things such as characters that were partially animated using rotoscope techniques. A mix of paintings and cgi models used to build interactive stages. Incorporating video loops to create realistic weather and environmental effects. A cast that was not made up of traditional martial artists but whose forms were still realistic and believable. Challenging conventional tournament design and focusing on a story with mature themes. Incorporating characters with and without weapons as well as including a trans character. It had been years since a single studio had pushed so many new ideas on the genre. Of course all of this innovation came at a price. The game did not look or play as Steel Hearts had intended. It took several years to get a mostly running version of the game ready. It left the developers wanting more, even years later they wanted to return to it and finish what they had started. No developer could realistically complete a project like this, it would bankrupt just about any studio. I am grateful that they were willing to give it their best. Steel Hearts showed what one studio could do for the genre. Imagine if every studio poured their heart and soul into setting their fighting game apart. The majority of fighting games today use the same graphics engine. They all have the same visual language, and because of that they have a diminished impact. Audiences are eager to see a return to strong aesthetics, graphics be damned. If you have a favorite fighting game that broke the mold I would like to hear about it in the comments section. As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!