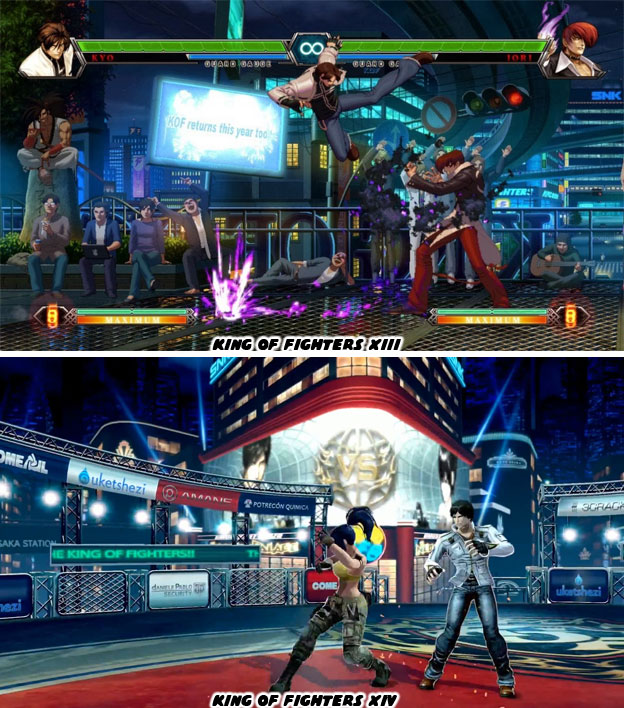

If you add in the time between the original Fatal Fury and KOF XIV there had been 25 years of the franchise, older than many people discovering fighting games today. When SNK officially transitioned to 3D, during KOF XIV, they tried very hard to capture the highly-stylized stages and characters. Audiences appreciated their dedication to the format. Characters maintained their unique proportions. Well, to be fair, most of the characters were not as swollen as they had appeared in the previous game. The costumes changed ever so slightly in the King of Fighters series however the stars each retained their moves, abilities and personality. Without consistency fighting games would have never taken off. The same rules applied for all the big franchises whether they were in 2D or 3D.

Between 1992-1995 developers were falling over themselves trying to get a fighting game to the market. Capcom had a certifiable hit in Japan and the USA with Street Fighter II. Just about the same level of success that Space Invaders enjoyed in the ‘70s or Pac Man did in the ‘80s was experienced by Street Fighter II in the ‘90s. No other game was single-handedly responsible for creating an arcade boom during that era. Many other companies tried to copy the formula verbatim, but few succeeded in winning any ground against Capcom. Some of the more innovative studios knew that they had to set their game apart from the competition. They couldn’t just repeat what was popular and needed to look elsewhere for inspiration. Since games were and continue to be about visual storytelling, the studios had to create a very strong visual language. The lead artist on each game could almost make or break the title. Some of the developers thought that asking directors from animé could help set their games apart. One of the biggest risk-takers was Technos. Their game Voltage Fighter Gowcaizer was released in 1995 on the Neo Geo platform. It featured the design work of animé veteran Masami Obari.

Masami had a very unique style of art. He cut his teeth working on many influential television shows and at a young age ended up directing original video animations (OVA) including Bubblegum Crisis and Dangaioh. His characters were very long and lean. The women were very busty and often wore revealing costumes. He wasn’t afraid to use bright colors either. This type of design worked well in animation, especially on the giant robot shows that Mr. Obari sometimes directed. His style was very popular and influenced a generation of artists in Japan as well as around the world. The types of characters he designed, the costumes / armor he worked with, the proportions that he used, the shape of the face and trademark eyes stood apart from his contemporaries, so much so that SNK hired him to create the Fatal Fury animé. It was only natural that a developer that published games for the SNK console asked him to create a library of characters for an original fighting game. It never gained much of a following but there was no mistake, nothing in the market before or after looked remotely similar to Voltage Fighter Gowcaizer (VFG). This was the type of game that budding fighting game designers need to dissect.

Mr. Obari created a world that had influences from animé, but also from live action television shows and even western comic books. The end result was a treat for the eyes. Each character in the game represented a sort of trope. Whether they were in the vein of a live-action sentai hero (like the Power Rangers), a traditional martial artist, a heavy metal vampire (really!) or comic book superhero, they each captured their respective genre. Their costumes, moves and poses all reflected the world they were drawn from. Just as important, every stage reflected this influence. The super hero for example, Captain Atlantis, looked like he had been designed during the silver age of comic books. With his bright costume, and underwear on the outside of his tights, he could have fit right into the Justice League. His stage was very American, it had turn of the century high-rises next to skyscrapers, a sort of cartoonish New York skyline. The view was covered up by an enormous billboard celebrating the upcoming Captain Atlantis movie. What could be more western than that? This level of storytelling applied through the entire game, in Mr. Obari’s unique aesthetic.

Voltage Fighter Gowcaizer was not the first game to repeat level design tropes. Things like rooftop stages, concerts, clubs, historical landmarks had been featured in different games. What VFG did however was put an example of each level trope in a single game. It set a sort of precedence. A fighting game could never be complete unless they also repeated the level choices from other games. Despite the memorable aesthetics the game never gained too much traction in Japan or the US. It didn’t have the control and balance that audiences had come to expect from fighters, especially those released in the mid-90s. Not even fantastic graphics, err, aesthetics could save the title. It nonetheless demonstrated that a great art director could develop a cast that broke convention. If only Technos would have spent a little bit more time working on the other elements there is no doubt the game would have been better received. No game before or since looked like Gowcaizer but it wasn’t the only fighter with a designer from outside the industry.

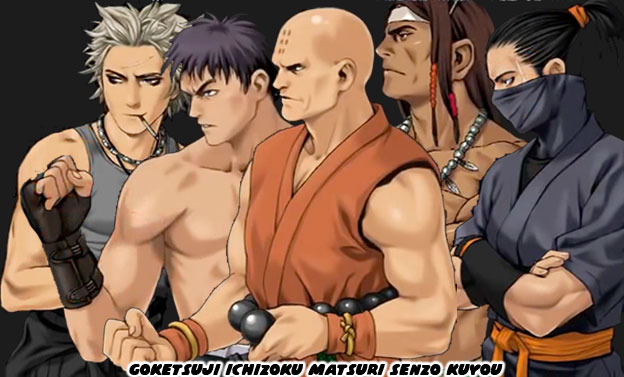

One of the oddest casts ever assembled debuted in 1993, before Gowcaizer. Over the years the characters in the game only got stranger and stranger until they included a delusional prince, a few elderly maidens and even a kindergarten sentai hero that turned into a dog. Seriously, I didn't make this stuff up. Professional illustrator Range Murata lent his services to the design team at Noise Factory. Range was a legend in the design community, his work on the animé OVAs Last Exile, and Blue Submarine No. 6 were gorgeous. His various magazine covers and art books were highly collectable. There were a number of other artists working with the developer, but Range’s unique style, his fingerprints were everywhere. Atlus published the game, Goketsuji Ichizoku aka Power Instinct in 1993. It did well enough to receive a number of sequels, spin-off titles and even cameos. The title started in the arcade and managed to stay in the arcade and in home consoles for almost two decades. Sadly the majority of gamers had never heard of it. Not that it stopped the cult-like following from within the fighting game community.

The various sequels had covered just about every trope that you could imagine. Every typical fighting game character, from the ninja to the karate master were in the series. What Range and more specifically Noise Factory did was to turn those tropes on their head. Not every character was heroic or noble. The Shaolin priest for example, Thin Men (also written Chinnen), had a violent temper and lusted after women and money. He was pretty much the opposite of what a Buddhist should aspire to be. The entire plot of the series revolved around a family power struggle. Every few years relatives of the Goketsuji clan, one of the richest families in the world, would fight for control of their empire. The longest-standing leader was not some sort of massive karate master, but instead a geriatric lady with some odd powers. Oume Goketsuji was cruel and manipulative, she had a younger twin sister named Otane that she despised. She actually trapped her in a box and threw her into the ocean at a young age. And you thought that Heihachi was cruel to Kazuya when he was a kid? Both sisters were 78 at the start of the series and aged along with the rest of the cast in the sequels. Despite their advanced ages they could fight better than people one quarter of their age. The developer had a unique reputation within the development community. They created an unlicensed Double Dragon fighting game called Rage of Dragons. It was designed by a Mexican developer named Evoga. They couldn’t get the rights to make a sequel to the 1995 SNK fighting game Double Dragon, created by Technos. So they created characters with similar looks and names, while Noise Factory and BreezzaSoft did the programming. Some of the characters were unique and some were lamentable but they lived on. The fifth game in the Power Instinct series: Matrimelee had a crossover with the Rage of Dragons cast, including Jimmy, Elias, Lynn and Jones

The characters appearing in the Power Instinct franchise actually came from every walk of life. Well, to be fair, they came from every walk of life depicted in a television show or comic book. There were dominatrices, martial artists, ninjas, heavy metal rockers, natives, princesses, robots and demons of every shape and size. Noise Factory created a fighting game series that stuck closely to its own canon yet at the same time never took itself too seriously. They wanted to create a game that was fun and memorable, not one that would necessarily be featured in tournaments. They wanted the story and characters to sell the experience, especially to their Japanese base. In order to accomplish this the majority of the figures each represented a slice of Japanese culture. They were not interested in capturing the global tropes that Gowcaizer or even Street Fighter were built on. Things like underground idols and their fan base, or maid cafes, magical girls, live action kid shows and even rockabilly dancers from Yoyogi Park.

Noise Factory were heavy-handed about the Japanese experience and how the Japanese perceived pop culture. They included the tropes from other games and television shows. There were many things that would have been difficult if not impossible to translate for the US market so a good portion was left in when the west was introduced to Power Instinct. This unapologetic school of design helped make it anything but another cookie-cutter series. While audiences in the west might not have been able to make heads or tails of the costumes, characters or ancient tournament hosts they were intrigued by their design. Some of the heroes and villains were familiar but many had looks that western players had never seen before. Remember that in the mid-90s the internet wasn’t readily available. People were not downloading animé or manga online. Many of the designs from Japan were still bold and unique. The games released by the studios were shaping the tastes of the young artists and programmers in the west. They wanted to see more characters and more games set in a world they didn’t quite understand. These games as well as those from Capcom, SNK, Sega, and Namco were setting a standard that the US had to match if not outright copy.

Of all the unique worlds and characters presented in the Goketsuji Ichizoku series there was one that really stood out. Groove on Fight was the third entry in the franchise. A tag-team fighting game that was released in 1997 for the arcade and Sega Saturn. In canon it was actually the last game in continuity. It was set 20 years after the events in the first game. There wasn’t too much to let people know they were looking at some sort of dystopian or idyllic future. The Goketsuji sisters were still alive and about 100-years-old. Other characters now had children fighting in their place. There were even robots and demons to contend with in the future. The game not only had character designs but entire stages rooted in the work of Range Murata. Some of the places visited had a very strong visual appeal to them. They went from whimsical; an enormous chess board inside a throne room, to downright macabre; a giant mechanical baby head that opened its eyes and cried. The characters featured in the title were also not like the ones in the previous games. They had more of a manga feel to them. As if they were really great fighters that dressed in stylish costumes instead of karate uniforms. All the aesthetic choices I think really worked to set the game apart from its contemporaries.

Very few people ever saw, let alone played Groove on Fight. Not that many people in the west ever got behind the Power Instinct series either. All of the games in the series were fairly well made and deserved a second look. They demonstrated how imaginative and unique a fighting game could be if they stuck with a strong aesthetic. Atlus didn’t have to follow the trends and in doing so were able to create a franchise that lasted almost 20 years. Sadly Noise Factory shut down operations in March 31, 2017. Not too long before this blog was posted. Their work should be studied and dissected by everyone hoping to design a fighting game or create characters of their own. Of all the studios that developed a fighting game there was one that stood head and shoulders above the rest. We will look at this game and the minor controversy surrounding it in the next entry. I hope to see you back for that! As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment