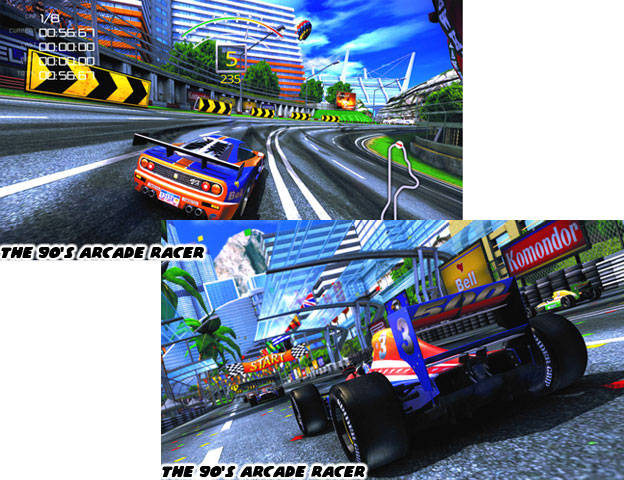

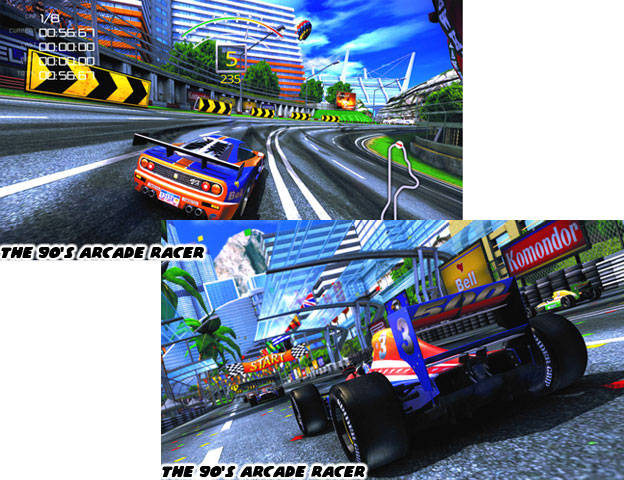

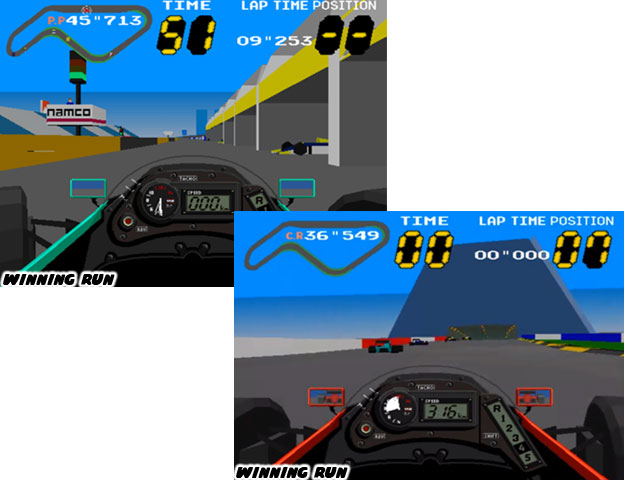

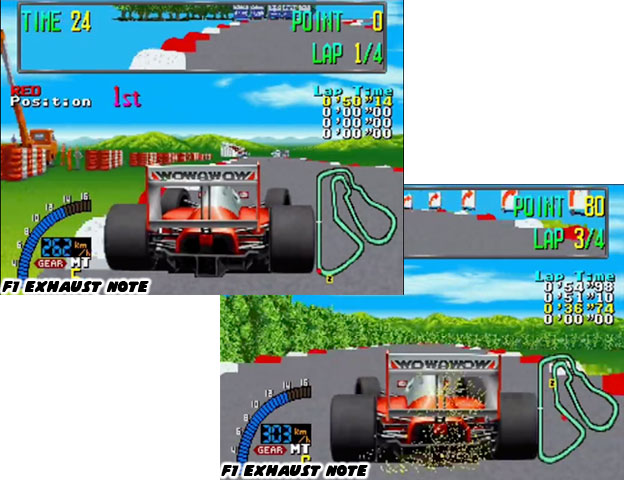

Sega had released its first 3D racing game years after Namco had put several in arcades. In the market the first game in a particular genre was usually the more successful title but this was not the case for the 3D titles. Time and technology made the later games appear superior by a wide margin. Sega completely overshadowed their competition thanks to Virtua Racing. A couple of years later however Namco responded with a game which would eventually outlive the competition. Ridge Racer debuted in 1993. The game had a few notable things going for it. It was based on modified street legal performance cars rather than Formula-1 cars. The game was set on the streets and highways of the fictional Ridge City rather than an identifiable race course. It featured textured polygons, already making it appear graphically much more advanced than Virtua Racing. Sega would not have Daytona USA in the arcades for another year. Many of these innovations would be copied time and time again by other studios.

The cars in Ridge Racer were not licensed but inspired by popular and affordable real world sport cars. The focus on attainable rides went over very well with audiences. Up until that point many visitors were driving race cars in popular circuits. These were vehicles that many would never even see in real life driving on tracks they might never visit. Many of these racing fans had come of legal driving age at the start of the '90s and were looking to buy or lease their first performance car. They would start with inexpensive consumer sport cars and then little by little tune them into real performance machines. Several of those drivers would be using their neighborhood streets and freeways as makeshift racing circuits as well. Namco was spurred in part to pursue the entire sub culture of street racing thanks to the success of the

the Megalopolis Expressway Trial films. The series was inspired by the Midnight Car Club, a notorious group of racers that ruled the Japanese freeway system in the '80s. Magazines used to glamorize their exploits and post their insanely fast times doing laps on the busy expressways. This insight and influence to street racing culture predated the Fast and the Furious movie franchise by more than a decade. It showed how much closer the game industry was to understanding their audience than the movie industry.

Ridge Racer created a spectacle around the tuned racer. Drifting around corners was a major selling point for the gameplay. In other titles losing even a little bit of traction caused a car to spin-out or lose momentum and the race itself. Instead the curving tracks of Ridge Racer lent themselves to drifting, allowing the player to block a pass attempt and add the much overlooked cool factor of overtaking an opponent by sliding around them. Experienced players learned when to brake and throw the steering wheel into the right direction to cause a successful drift, sometimes avoiding narrow walls by mere inches and never straightening out completely for several hundred meters at a time. It could be unnerving in the first person perspective watching a cliff wall directly in front of the car while sliding in the right direction. The entirety of Ridge City seemed to celebrate this race culture. Audiences lined the roads, "race queen" models held up starting cards and a news helicopter followed closely overhead. Even a radio station (labeled 76.5 / Ridge City FM in Ridge Racer V) was dedicated to providing the music and commentary for the racers driving in and around the town. The game was very flattering to the "tuners" that players were becoming in the real world.

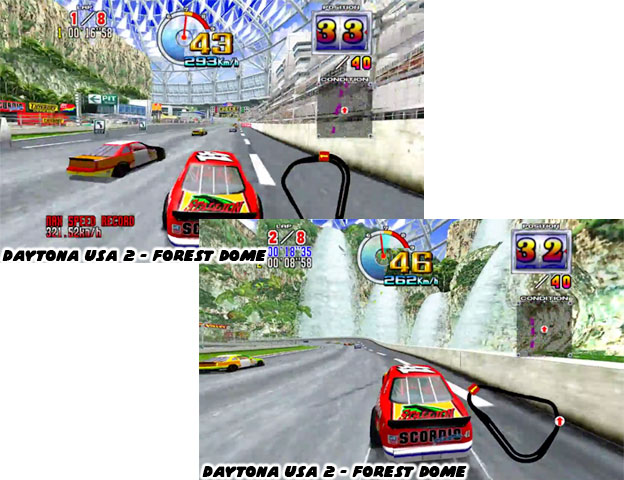

Ridge Racer got a sequel in 1994 it was out the same year as Daytona USA and Ace Driver. The graphics, courses and gameplay in Ridge Racer 2 had been turned up by a notch. What the sequel needed however was a major upgrade and it simply didn't have it. At the very least Namco had the street racing scene pretty much locked up but in other genres they had a hard time keeping up. A little known R&D group called AM5 released Sega Rally Championship in 1994. That team was probably best known for creating the Crazy Taxi series in 1999. At one point the collective was also known as Hitmaker and Sega Rosso while developing console releases and adaptations for Sega. What audiences did not realize however were that the founding members of AM5 used to work for Namco. They had created the original Ridge Racer and had jumped ship to make the Sega racing games even better.

AM5 took everything that they had learned in Ridge Racer, especially the drift physics and used that on a World Rally Championship-type game. Rally races feature heavily modified cars that have been strengthened for endurance racing. The races can actually take place on any type of course, both on road and off road, as well as in any type of weather and even at night. The course maps are handed out before the start of each race and each team has to have a driver and navigator. The navigator keeps an eye on the map and calls out the coordinates before each turn so that the driver does not go blindly through twisting roads. The studio actually licensed out a few real rally cars for their game, including the Toyota Celica and Lancia Stratos. The game made great use of different terrain, like gravel, mud, sand, asphalt and snow to challenge the driving ability of players.

Namco countered with Dirt Dash in 1995. It featured some great new gameplay elements and a diversity of road types as well. There were three different types of cars, unlicensed of course. A buggy type for beginners, an off road truck for novices and a sport car for experts. The cars were unique in that they had body panels that could take damage, flap in the wind and even break off depending on the severity of a crash. The Sega Rally cars did not feature those details. Actual rally cars seldom finished a race, let along a stage, without suffering some sort of damage. Sometimes the damage was cosmetic, like a hood or fender getting torn off by a tree or rock. Sometimes the damage was more severe like a wheel breaking off from the force of a hard landing. In either instance the cars were usually very tough and could continue under their own power. In Dirt Dash each car was voiced by a different navigator, they all had a distinct personality as well. They complimented the driver if they raced effectively and reprimanded them if they were sloppy. The game even featured a few shortcuts and alternate paths for repeat players to discover. The game was great in design and execution but it felt too little too late for many gamers. Graphics, level design and gameplay had made the Sega racers untouchable in the eyes of many arcade visitors. Namco had lost the F1 and Rally fans seemingly overnight. When Sega took on the Stock Car and GT fans the entire industry took notice. The next blog will look at how Sega set the standard yet to be beaten.

As always if you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!