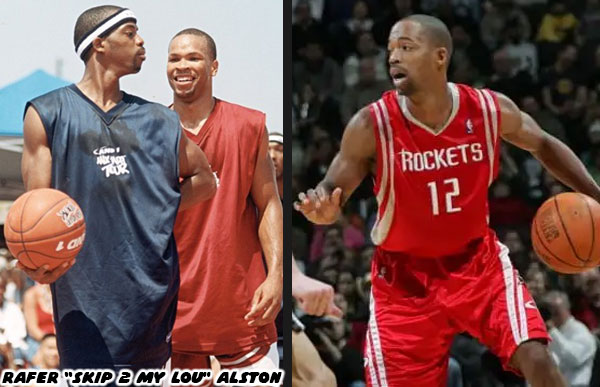

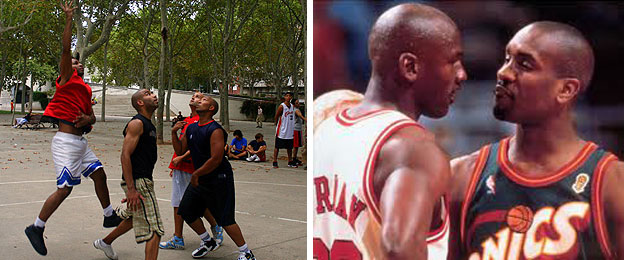

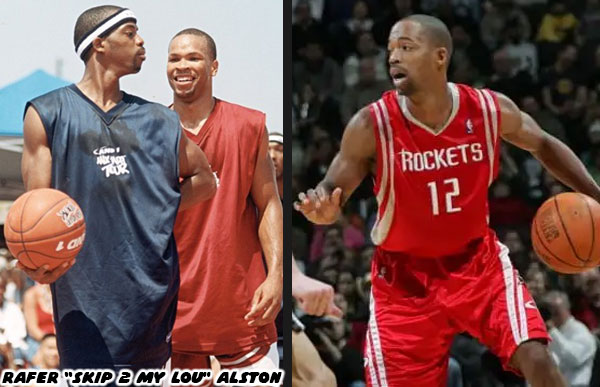

The indication that the US was ready to elevate the status of street fashion, Hip Hop music, and Black culture in general happened in the late ‘90s, and early 2000’s. The rise of athletes like Allen “The Answer” Iverson, Stephon “Starbury” Marbury, Gary “The Glove” Payton, and Rafer “Slip 2 My Lou” Alston were unlike the previous generation of pro athletes. They were gifted with skills, and had built their reputations in college, but more important to many in the streets during the summertime. The NBA, like many professional leagues guarded their image. They made sure that coaches, and players dressed in suits while doing interviews, or sitting in the sidelines while injured. They would fine players for breaking any codes of conduct in games, and in public as well.

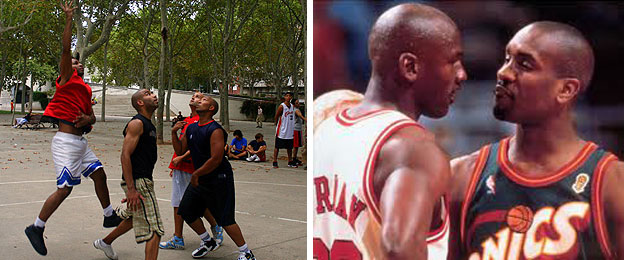

To many the polished images that the league presented was bland, and predictable. Seeing clean-cut college prospects move into the pro ranks was becoming stale. Suddenly there was a rise in rash, tattooed, outspoken, and genre-changing athletes. Young players that

had the audacity to not only talk back to Michael Jordan, but also to

cross him up, and humiliate him on court. The NBA couldn’t get them to conform to the old ways. When the organizers realized that the players with street roots represented a large population of their audience they changed course, and started using them for marketing. They started highlighting rappers sitting court-side on television, they started inviting Hip Hop acts to perform at the All Star Game, and even loosened their rules on visible tattoos.

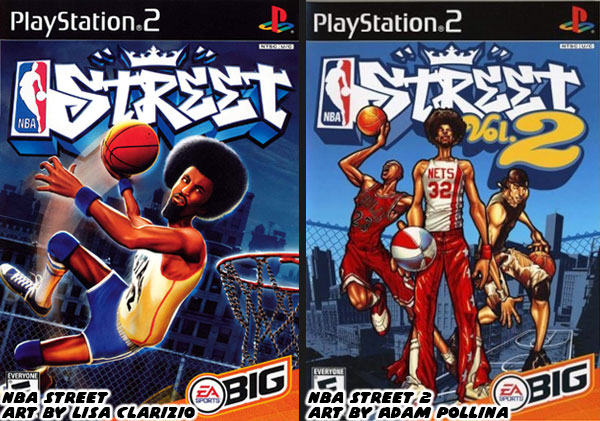

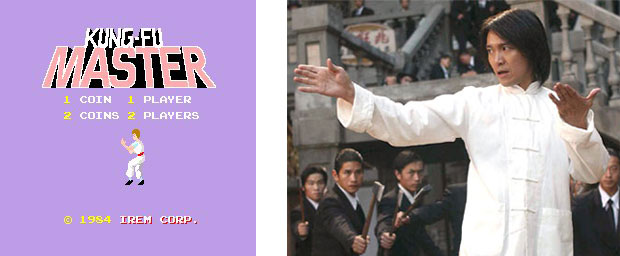

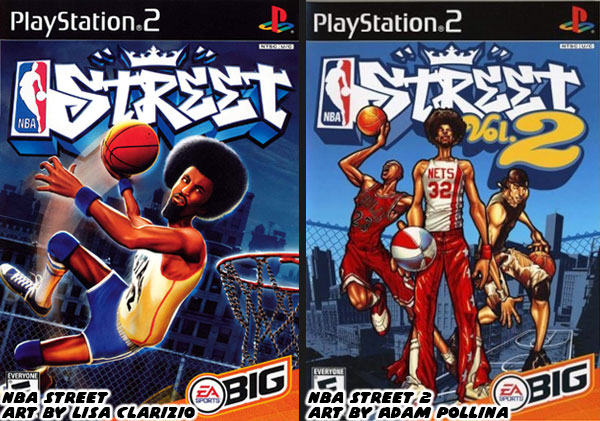

Electronic Arts developed a number of pro sports video games, but they too felt that it was high time to incorporate more street culture into their library. So they had a sister developer called EA Big start creating action sports titles, like the iconic SSX Tricky snowboard game. But more important they released NBA Street in 2001. On the cover was a fictional player named Stretch Monroe. He was sort of avatar of the classic NBA stars from the ’70s. He was somehow still actively holding down the game in the streets against players more than half his age. The world would never be the same following its release. The studio would also add NFL Street, and FIFA Street into their catalog. They were essentially smaller groups of the top players, and teams, playing a looser version of the sport on the playground. Rather than be more like a simulation game, the focus was more on capturing the arcade experience. NBA Street was essentially a call back to the classic NBA Jam arcade hit from a decade earlier. I called

NBA Street one of my favorite games of All-Time. The game had smooth controls, and an easy to learn combo system, which allowed you to crossover opponents for bonus points. It was as if EA Big figured out how to incorporate the combo mechanics of the Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater series, but put it into a sports game.

NBA Street was a breath of fresh air. I was never a fan of the traditional sports games. I didn’t care about building franchises, trading players, or grinding through seasons. The more realistic those titles were the less interesting they became to me. Giving slightly exaggerated abilities to a handful of star athletes made them feel more like super heroes, and less like mortals in the game world. Suddenly the game play had much more potential to me. The same could be argued of Hawk, and his fellow pro skaters. They could survive impossible drops, perform back-to-back tricks mid air, and grind rails without losing momentum. There was still a lot of realism in the games, but reality was not the goal. It was more on the fantastic spectrum of what was humanly possible. In addition to the brilliant game play were the visuals. The aesthetic of the players in the franchise was more animated. The proportions employed by EA Big was the predecessor to the All Star Vinyl figures by Upper Deck.

You could imagine how much I loved the look of the players in this game. They were the kinds of basketball players that I would draw, but finally animated. The impact of the Street series on me, and on basketball fans in general could not be understated. If you don’t believe me

GQ called NBA Street 2 the greatest basketball game ever made. It would be hard for me to counter that argument. The game was an instant hit, and spawned a number of sequels. Yet like the Hawk franchise, the greedy publisher forced the developers to crank out sequels with diminished quality over the following years.

I predicted that the market would be flooded with streetball games in 2005. The team at EA Big in Canada didn’t have time to innovate, they didn’t have time to look for newer or better game play options. They substituted evolution by adding all sorts of over-the-top gimmicks. Eventually the series would burn out. However the template they created would be picked up by indy developers.

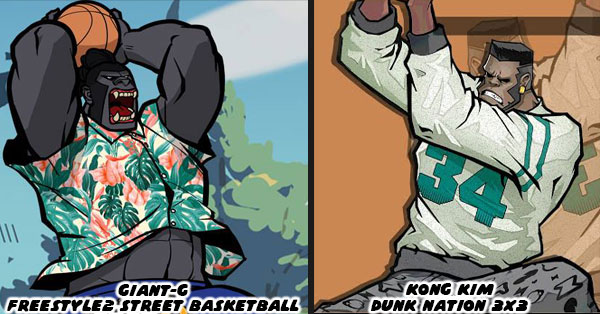

JoyCity the South Korean company was founded in 1994 as Chung Media and was later renamed to JC Entertainment in 2000. They released a an MMO PC game called FreeStyle Street Basketball in 2004. The game did well over the years, as did many other MMOs coming out of South Korea. Freestyle2 Street Basketball came out in 2015. The game did even better, and expanded the universe of playground basketball characters that JC Entertainment had established. Their cross platform successor 3on3 Freestyle Basketball originally came out for PC / Steam on Dec. 2016, and Xbox Aug. 2018. Other studios were eager to cash in on the trend. Beijing Halcyon Network Technology Co., LDT released

Dunk Nation 3x3 in 2017. The Asian collective All9Fun which developed games for Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macao released

Basketrio: Allstar Streetball in 2020.

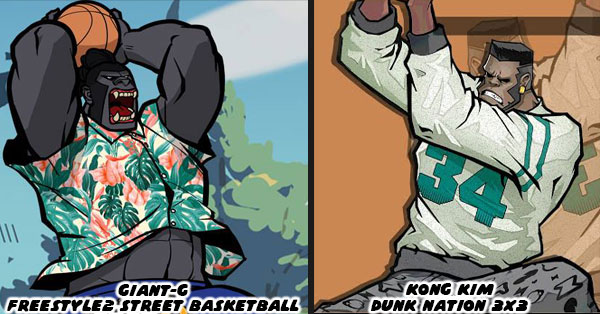

As a fan of the Michael Lau, and by extension urban vinyl school of design I could tell that his work in the early 2000’s had certainly rubbed off on the character designers working in South Korea, Beijing, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The style of the characters, the proportions, the attention to outfits, and presentation was unmistakable. Lau was not the only influence, Eric So, CoolRain, Brothersfree, and Jason Siu also colored the aesthetic that went into toy, game, and collectable art for the next two decades. Looking at the designs featured in the games by JC Entertainment, Halcyon, and All9Fun was a master class in bridging the aesthetic, culture, and shifting role of online gaming.

Let’s start with the stylized characters featured in all of the above mentioned streetball games. What really stood out to me were the styles of the designs. When the studios created basketball players, they were very much in the vein of Michael Lau, Kadir Nelson, and Chris Brunner. I would even put my name as a contributor of that style even if I only impacted 0.01% of the artists out there. The trio created some lanky, stylized, forms that worked great for basketball. They even made sure that sneakers these cartoonish character wore were large, and reflected the style of the time. It didn’t matter if their kicks were licensed or not. They made sure that players could read the fashion of each athlete which gave them additional layers of personality. The type of physical build they put forward didn’t work with all sports, but on the fast paced game of basketball it was perfect. These designs worked amazingly well in animation. The long arms, and legs, the oversized hands, the flat, expressive faces were the ultimate athletic canvas.

I noticed that the Asian studios were quick to use street culture, to use Hip Hop as the backdrop of many of their titles. The graffiti, the fashion, the music, the overall visual language. The oldest trailers for Freestyle Street Basketball had a graffiti artist using spray paint to bring the characters to life. A deejay was scratching beats on a turntable while a black basketball player without pupils was putting together a freestyle routine. This character would eventually be named Deacon, and featured prominently over the years. Many years later when Freestyle2 was announced a new Black character with gold hair named Leo debuted. He was essentially a new take on Deacon. Almost every studio was quick to feature Black characters in their opening animations, and online marketing as well. This was a form of signaling to the community that the streetball was authentic, however the staring roles didn’t go always go to Black characters. At least not in the early days of the streetball MMOs.

The star characters of each of the JC Entertainment games fit a similar model. The oldest star character the studio created was Saru, in some of the oldest advertising, and trailers his jersey actually read Sabu. The character wore red, and black, the classic Chicago Bulls colors. Had a tribal tattoo sleeve. He was essentially the prototypical cool streetball player. His design influences were a cross sample of elements that the Asian market would identify, even if they weren’t familiar with the stars in the NBA, or US playgrounds.

The character’s name, and his jersey was more than a nod to the ‘90s era Bulls which were known the world over. The outfit was based on the protagonist Saru gang from the highly influential Tokyo Tribe manga / anime, which was first published in 1993, and was serialized in Boon magazine between 1997-2005. This was often the first exposure that many fans in Asia had to Hip Hop culture. Even if they had not known anything about Tokyo Tribe the young basketball hero in a red jersey was also seen in Slam Dunk. The manga was first published in 1990, and went on to get translated into multiple languages as well. It was a primer for many fans to basketball culture. Saru’s design would be easily identifiable as the hero to the Asian market, just as Stretch was recognized as the star of the NBA Street series in the west.

The next hero of the Freestyle series was Jack. By the time the sequel was released in 2015 the urban vinyl school of design had already changed the looks of characters in games, and animation. The reception to lanky heroes was welcome in several genres, especially basketball. The cool culture was street culture, Hip Hop was everywhere, and style was more important than substance. The athletic uniform was out the window, as Jack played shirtless, in leather pants, and sneakers. It was an absurd outfit for playing, but the cool factor was unarguable. At the same time JC Entertainment still featured characters in traditional outfits, but was letting players create custom characters that wore all sorts of costumes, and accessories. The studio had essentially placed Freestyle2 in a universe similar to Lau’s gardeners. People walked around with boxes on their heads. Or there were animal people, or cyborgs inhabiting this world where everything was settled through basketball tournaments.

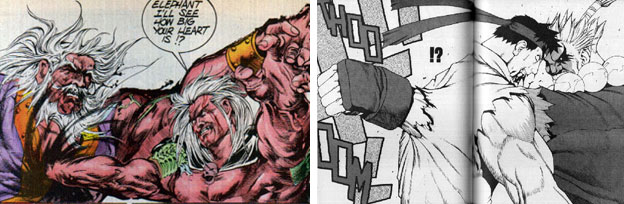

The thing that always bothered me about the street basketball games coming out on Steam, mobile, and consoles from overseas was that Black characters always seemed to be relegated to supporting characters at best, or villains at worst. Well, actually there could be subtext in the designs that was even worse than evil, and that was outright racist. Dark skinned characters were sometimes portrayed as aggressive, tough, and sometimes ape-like, if not outright apes. I wish I could say that this was a trope that was abandoned generations ago, but it would still rear its ugly head from time to time. The light-skinned champion against these apes, or savages in a Black setting was a tradition that had always bothered me in all media.

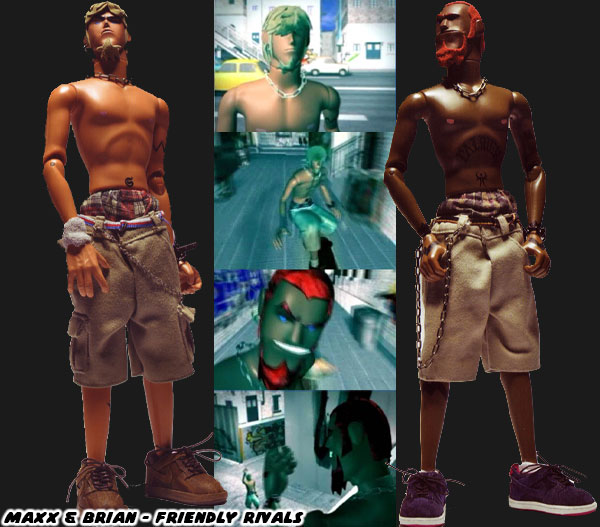

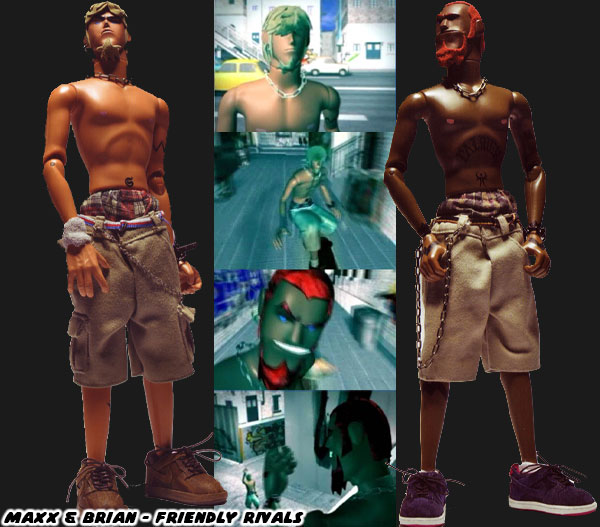

It went back to the days of Tarzan of the Apes, the adventure books from 1912 featured the white champion as not only being the strongest, and bravest warrior in all of Africa, but he could also talk to the animals. In essence he was superior to every Black man on the continent. This type of white savior story had spread around the world for decades, coloring other cultures perception of dark-skinned characters. As a Mexican-American I was sensitive to how minorities were portrayed in media. I could never imagine how a Black kid would even react when faced with the same tropes. Even Michael Lau was not immune from centering the gardener universe around the light skinned Maxx. His best friend, and rival Brian was Black. They went back-and-forth against each other in skate contests in the pages of East Touch magazine.

Having the pair as skaters, and not the more stereotypical basketball players was a refreshing change of pace. Brian, and his girlfriend Elsa not only added much needed color to the lineup, they were symmetrical balances to Maxx, and Miss. The Black characters also demonstrated that no matter how cool Maxx was, the Black kids in the neighborhood were just as cool. The show of diversity certainly lent more street cred to the gardeners, but throwing anthropomorphic animals into the world of figure art could also be seen as exploitative out of context. Say for example Coolrain releasing a series of vinyl figures called the Dunkeys, as in Slam Dunk Monkeys. Of all the animals he could have gone with maybe monkey basketball players was not the wisest of choices. I know that falling back on ugly stereotypes, or insensitive racial jabs wasn’t Lau, or Coolrain’s intent, as it wasn’t for most of the character creators at the time. This wasn’t a fast, and hard rule.

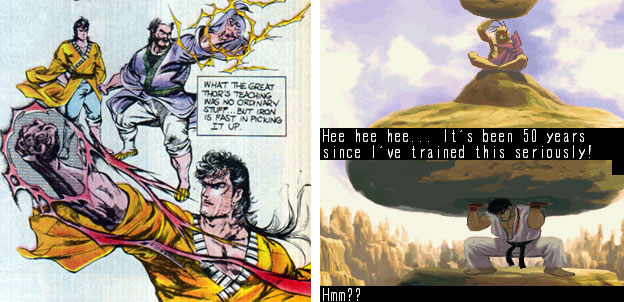

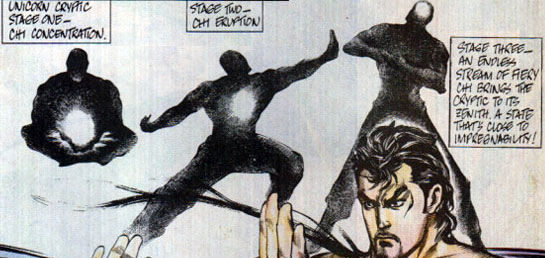

Black heroes would get some moments to shine in Western culture. The comic book character T’Challa the Black Panther was created in 1966 by Stan Lee, and Jack Kirby. Luke Cage created by Archie Goodwin, George Tuska, Roy Thomas, and John Romita Sr. debuted in 1972. The most recent Marvel breakout star, the biracial Miles Morales created by Brian Michael Bendis, and Sara Pichelli debuted in 2011. These were all examples of white creators putting Black heroes into pop culture. There were other Black stars in the Marvel, and DC books after the creation of the Black Panther, but new comics rarely presented Black characters as the focal point. This fact was even more pronounced in Asian countries. Of course this had a lot to do with the ethnic makeup of the nations. This didn’t stop the creators from using Black supporting characters to ground their work.

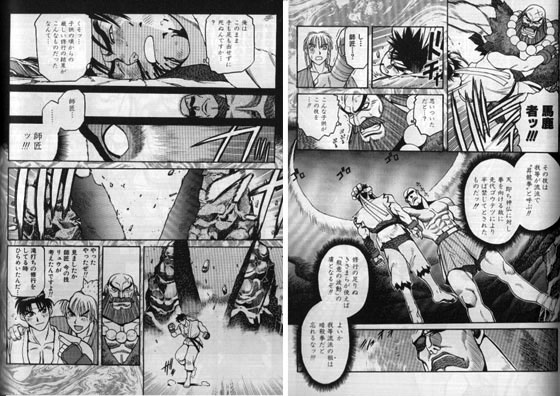

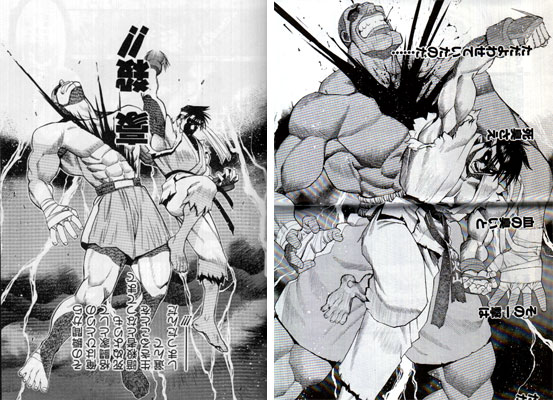

In Slam Dunk for example the main character followed the pattern of manga heroes. Sakuragi Hanamichi was the typical high school Japanese kid, that happened to be a loser with the girls. He would become a better person, get a girlfriend, and shine as a star athlete in the end. The respected team captain was the Black center Akagi Takenori. Akagi was the more physically imposing of the two, and wiser by far, but it would be absurd to think that a Black character would be the lead character in early '90s Japanese stories. The manga Tokyo Tribe, and its sister series Tokyo Graffiti borrowed Hip Hop culture, and fashion wholesale. The main character was the deejay Kai Deguchi who had a fresh line-up, listened to rap, and went clubbing with his crew. His rival was Mera, the dark skinned, big-lipped heavy in a fur coat. If you didn't know better you could swear these heavily were biracial characters, if not heavily coded Black characters.

By focusing on somebody that looked like them the books helped Japanese kids understand Hip Hop culture, or appreciate the sport of basketball. Yet there was something much deeper in understanding the layers of Hip Hop, and streetball that didn't necessarily come through in the manga, whether or not the star was Asian, or Black. This was something that I had referred to

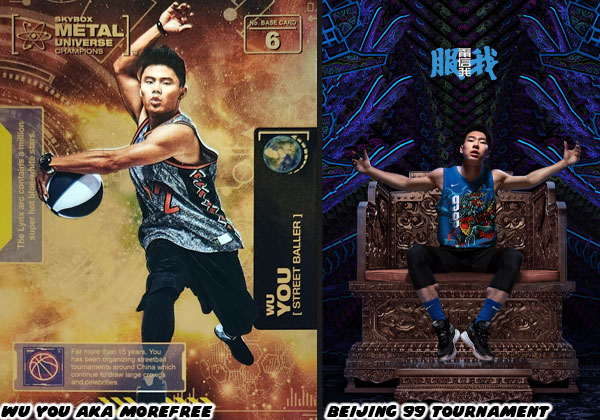

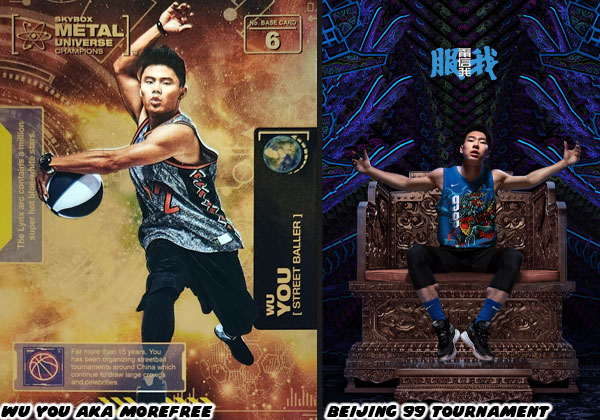

on a much earlier blog about the rise, and fall of streetball. I'm going to paste something from that exact series right here regarding the influence that streetball had on China. There was a young man that became hooked on the early AND1 mix tapes, and tour,

Wu You aka MoreFree is the Chinese legend that helped spread the gospel overseas. He would challenge visiting NBA players to 1-on-1 battles, and dazzle them with his skills. As audiences learned to differentiate streetball from traditional basketball then local courts started building reputations, just as they had done in New York, Chicago, and LA.

Dongdan Court in China is considered the Holy Land. When the summers heat up you could find the best players competing at Dongdan.

A Westerner might call the Chinese "biters" or just laugh at their attempts to incorporate Black fashion, and language into their lexicon. But then again where did they get the idea that streetball is about fashion and tricks? It had a lot to do with how the west presented themselves in the mix tapes and of course in the entertainment industry. Asia was quickly getting sold on the idea that streetball was about entertainment, and not basketball. The big shoe companies learned that there was no one approach that could appeal to all audiences. They had to be sensitive to differences in culture, language, art, music, and presentation. Nike couldn't simply release USA Battlegrounds merch in mainland China featuring the name of Holocombe Rucker Park in Harlem, or the Venice Beach Courts. The Chinese had no point of reference to NYC, or LA's street roots. Dongdan Court on the other hand would make more sense. That was why they began creating custom streetball campaigns in their biggest markets. The

Beijing 99 campaign by Nike incorporated many symbolic characters from classic tradition, and had the best street players from around the country compete. This was the type of world that influenced creators like Michael Lau, Santa Inoue, and their contemporaries.

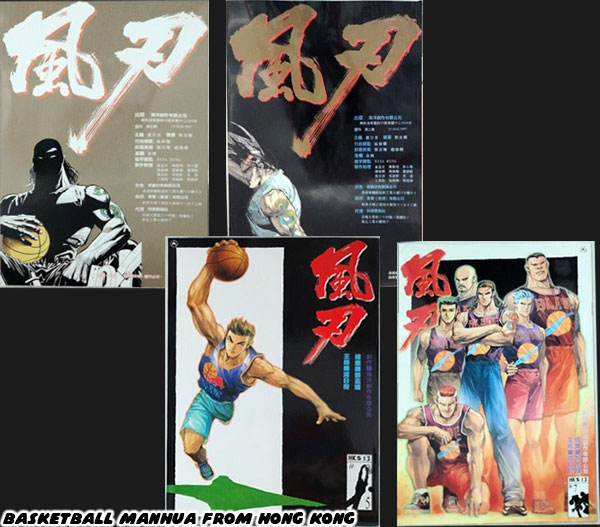

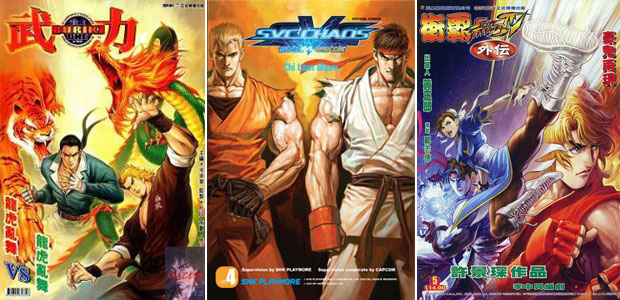

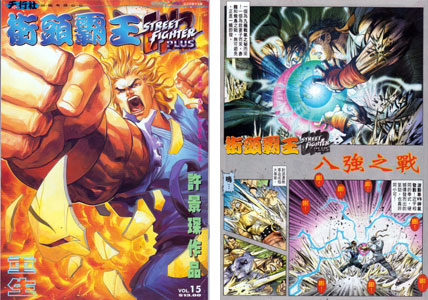

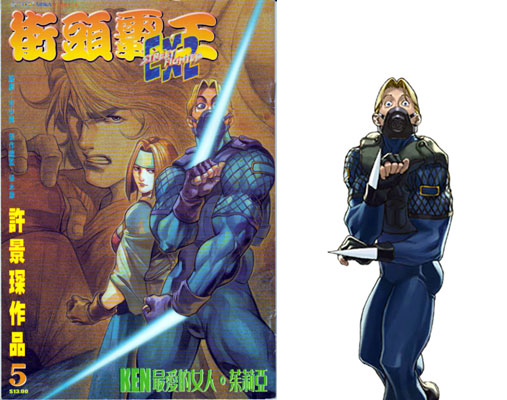

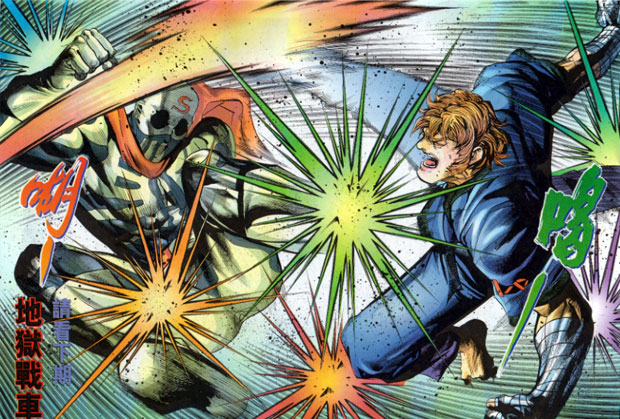

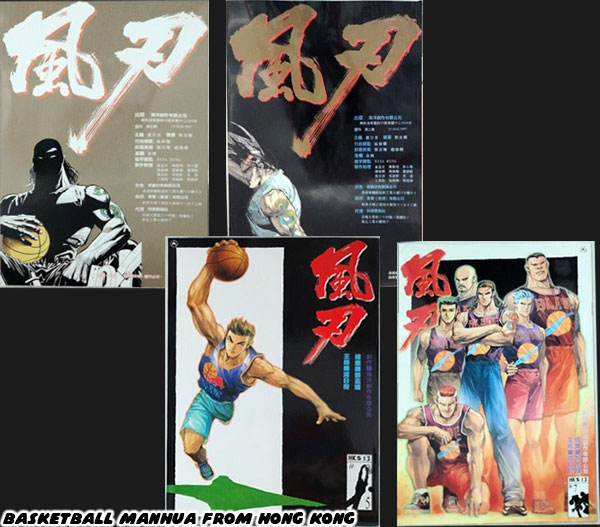

At this point the basketball player, and even streetball legend was a cultural standard in Asia. This was thanks to the exposure of AND1, and the Mixtape Tour at the end of the '90s/early '00s. While Japan was known for its various basketball manga, including the title "REAL" which focused on wheelchair basketball, the creators in Hong Kong had already released streeball manhua. In every instance, whether it was a comic, anime, or video game the light-skinned hero would remain the star of most of the popular basketball titles. Would this change in the future? I couldn’t tell you. I could however say that the approach that most of the streetball games from overseas did push the genre in some fresh ways. I will look at this in the next entry of the series. Were you a fan of any of the EA Big Street games? Did you ever identify with a minority character in any game or comic more than the main character? I’d like to hear about it in the comments section. As always if you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!