In recent years it has been the entertainment industry that has sent the most mixed messages. When we turn on the TV or go to a movie we are now more likely to see streetball than ever before. From inline skate-wearing streetball (who came up with that crap?) players doing a McDonalds spot to an MTV reality series. We are being sold streetball as the new form of entertainment and pop culture.

One of the very first campaigns that a young Lebron James was signed up for was the host of the Battlegrounds Tournament. He had yet to set any sort of scoring records, and was many years from winning a championship. Nike wanted to make sure that they kept the phenom in the eyes of the public. So some of his earliest media training was breaking down the street game to audiences in a weekly televised tournament.

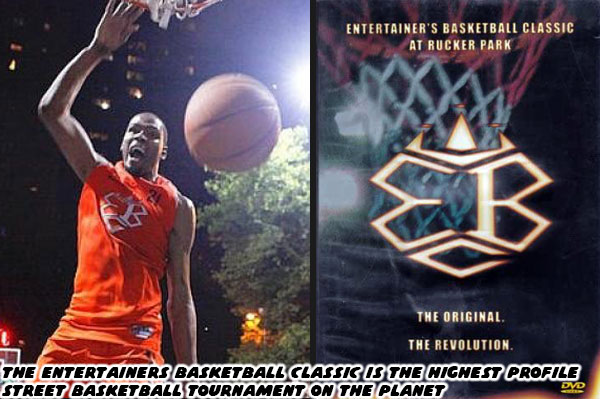

The EBC tapes were entertaining, but also very selective in the message. Many players and organizers in the EBC called the AND1 tours and players fake and choreographed. Going as far as to compare them to clowns. By branding themselves with the EBC and the local legends like Alimoe and the Bone Collector, Reebok hoped to gain some street credit.

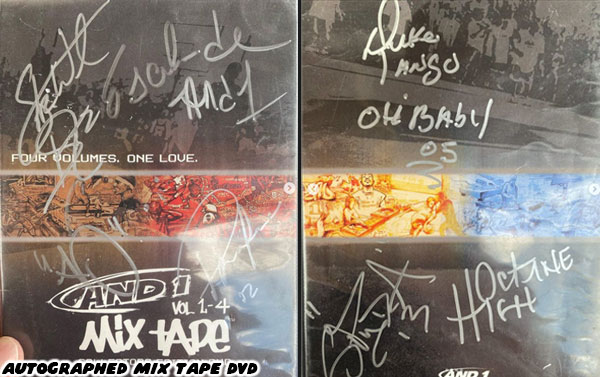

AND1 was leading the media blitz by taking their tour around the country and having the stops filmed by ESPN for a new reality series titled Streetball. In effect it began giving fans what they wanted in big venues, and televising them for those that couldn't make the live stops. The first season of Streetball was so successful that ESPN and AND1 decided to follow-up in 2004. The mix tapes had now become a television phenomenon.

A must-read for basketball fans is Sole Provider. The book is a Nike basketball history written by Scoop Jackson. Rarely seen grassroots and more mainstream campaigns are highlighted in the book.

Right on the heels of the Freestyle campaign Nike came out with the Battlegrounds series. Proving that Nike had a hold on both the entertainment aspect as well as real-street aspect of basketball. Both campaigns were much larger and farther reaching than any of the grassroots campaigning that they had done. This was the series that featured a young Lebron James fresh from his prep school right into the NBA.

The east and west coast champs never did battle to determine the best in the US, Fans and critics alike chided Nike for the decision. However in 2003 Nike decided to increase the stakes by hosting the Battlegrounds tournament in several major cities and then having the winners in those cities, plus the kings from the year before, battle to see who was the undisputed "king of the courts."

One question remained. How was the country, not just the streetball fan, thinking about all of this exposure? Bean counters, focus groups and test marketers aside, the dollar does all the talking! Tapes from Reebok, AND1 and Nike eventually made their way to retail outlets like Best Buy, Target, and Walmart. They they sold better than most movies over the next few years.

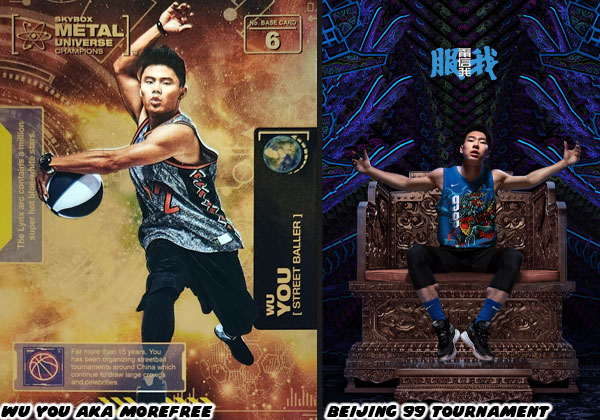

The presence of streetball has only grown since this blog was written in 2005. There was a young man that became hooked on the early tapes, and tour, Wu You aka MoreFree is the Chinese legend that helped spread the gospel overseas. He would challenge visiting NBA players to 1-on-1 battles, and dazzle them with his skills. As audiences learned to differentiate streetball from traditional basketball then local courts started building reputations, just as they had done in New York, Chicago, and LA. Dongdan Court in China is considered the Holy Land. When the summers heat up you can find the best players competing at Dongdan.

The EBC tapes were entertaining, but also very selective in the message. Many players and organizers in the EBC called the AND1 tours and players fake and choreographed. Going as far as to compare them to clowns. By branding themselves with the EBC and the local legends like Alimoe and the Bone Collector, Reebok hoped to gain some street credit.

AND1 was leading the media blitz by taking their tour around the country and having the stops filmed by ESPN for a new reality series titled Streetball. In effect it began giving fans what they wanted in big venues, and televising them for those that couldn't make the live stops. The first season of Streetball was so successful that ESPN and AND1 decided to follow-up in 2004. The mix tapes had now become a television phenomenon.

A must-read for basketball fans is Sole Provider. The book is a Nike basketball history written by Scoop Jackson. Rarely seen grassroots and more mainstream campaigns are highlighted in the book.

Right on the heels of the Freestyle campaign Nike came out with the Battlegrounds series. Proving that Nike had a hold on both the entertainment aspect as well as real-street aspect of basketball. Both campaigns were much larger and farther reaching than any of the grassroots campaigning that they had done. This was the series that featured a young Lebron James fresh from his prep school right into the NBA.

The east and west coast champs never did battle to determine the best in the US, Fans and critics alike chided Nike for the decision. However in 2003 Nike decided to increase the stakes by hosting the Battlegrounds tournament in several major cities and then having the winners in those cities, plus the kings from the year before, battle to see who was the undisputed "king of the courts."

One question remained. How was the country, not just the streetball fan, thinking about all of this exposure? Bean counters, focus groups and test marketers aside, the dollar does all the talking! Tapes from Reebok, AND1 and Nike eventually made their way to retail outlets like Best Buy, Target, and Walmart. They they sold better than most movies over the next few years.

The presence of streetball has only grown since this blog was written in 2005. There was a young man that became hooked on the early tapes, and tour, Wu You aka MoreFree is the Chinese legend that helped spread the gospel overseas. He would challenge visiting NBA players to 1-on-1 battles, and dazzle them with his skills. As audiences learned to differentiate streetball from traditional basketball then local courts started building reputations, just as they had done in New York, Chicago, and LA. Dongdan Court in China is considered the Holy Land. When the summers heat up you can find the best players competing at Dongdan.

A Westerner might call the Chinese "biters" or just laugh at their attempts to incorporate Black fashion, and language into their lexicon. But then again where did they get the idea that streetball is about fashion and tricks? It has a lot to do with how the west presents themselves in the mix tapes and of course in the entertainment industry. Asia is quickly getting sold on the idea that streetball is about entertainment and not basketball. The big shoe companies learned that there is no one approach that can appeal to all audiences. They have to be sensitive to differences in culture, language, art, music, and presentation. Nike couldn't simply release Battlegrounds merch in mainland China featuring the name of Holocombe Rucker Park in Harlem. The Chinese have no point of reference to NYC. Dongdan Court on the other hand would make more sense. That was why they began creating custom streetball campaigns in their biggest markets. The Beijing 99 campaign by Nike incorporated many symbolic characters from classic tradition, and had the best street players from around the country compete.

Today the legacy of street players earning their names and respect on the blacktop is virtually gone. Courts that used to be the stuff of legend are now on cable, and satellite. Games are broadcast online every summer all over the world. With thousands of games, places, and players to choose from then why would the Rucker stay relevant? Or does the saturation of summer tournaments the world over make the EBC more important now? What is important now changes depending on whom you talk to.

The biggest legends in the history of the game are not even spoken of in most parts of the world. There are a lot of ignorant people in the US as well that don't know why names like "Pee Wee" Kirkland or "Fly" Williams are revered in certain streetball circles. Don't blame China if they have no concept of the ghetto, or hood mentality. They dress and act the part because they are trying to be part of a scene. That's the scene they see in music videos and mix tapes. Whether that scene is real and that message is correct is entirely up to them. In some way those Chinese streetballers cannot identify with their own culture. It doesn't reflect the freedom, creativity, and self-expression celebrated in global street culture.

Today the legacy of street players earning their names and respect on the blacktop is virtually gone. Courts that used to be the stuff of legend are now on cable, and satellite. Games are broadcast online every summer all over the world. With thousands of games, places, and players to choose from then why would the Rucker stay relevant? Or does the saturation of summer tournaments the world over make the EBC more important now? What is important now changes depending on whom you talk to.

The biggest legends in the history of the game are not even spoken of in most parts of the world. There are a lot of ignorant people in the US as well that don't know why names like "Pee Wee" Kirkland or "Fly" Williams are revered in certain streetball circles. Don't blame China if they have no concept of the ghetto, or hood mentality. They dress and act the part because they are trying to be part of a scene. That's the scene they see in music videos and mix tapes. Whether that scene is real and that message is correct is entirely up to them. In some way those Chinese streetballers cannot identify with their own culture. It doesn't reflect the freedom, creativity, and self-expression celebrated in global street culture.

Every nation observes the culture of streetball a little bit differently. In Italy one of the popular crews is known as Da Move. It seems that the Nike Freestyle campaign went right to the heads of these players "Aig $cream (ice cream?), Da Helicopta, Downtown, Flashback, Jack Da Rippa and K-lean." The interpretation of streetball is unique for these players, to the best of my knowledge they were the first to take the freestyle concept to the clubs. That's right, dance clubs! They'll show up and do some freestyle basketball and everything seems to be cool with other people at the club and even the club owners.

Da Move sets are well rehearsed and akin to a show that Nike would put on with their freestyle team. They have even begun performing as basketball halftime acts. It is unknown if something like that would ever fly in the US however. Again there is nobody to blame about the way Italian street crews are interpreting streetball other than the media (internet included) from the US and more recently Canada. They will mimic and try to incorporate into their own culture the things that they are shown and taught.

Are players supposed to assume that streetball is either one or the other? Can they be both a freestyler and streetball player? Are there penalties for being a freestyler and not a person that plays basketball? Is earning a name more important than naming yourself? Who cares what these players do? If you are reading this then you should care what other players and countries are doing with the streetball game. Moreover we should not get so hung up on what the players do but look at what the industry is doing to perpetuate these confusing messages. Every action has a consequence, even if it is small in and of itself, the bigger picture is made up and dictated by all of these individual actions. If some kid in China has braided hair and is wearing a do' rag while downloading Jay-Z MP3's and Hot Sauce clips, then the big picture of streetball is going to be changed. The actions taken by the industry make even bigger impacts to streetball. We'll explore these in the next part.

Da Move sets are well rehearsed and akin to a show that Nike would put on with their freestyle team. They have even begun performing as basketball halftime acts. It is unknown if something like that would ever fly in the US however. Again there is nobody to blame about the way Italian street crews are interpreting streetball other than the media (internet included) from the US and more recently Canada. They will mimic and try to incorporate into their own culture the things that they are shown and taught.

Are players supposed to assume that streetball is either one or the other? Can they be both a freestyler and streetball player? Are there penalties for being a freestyler and not a person that plays basketball? Is earning a name more important than naming yourself? Who cares what these players do? If you are reading this then you should care what other players and countries are doing with the streetball game. Moreover we should not get so hung up on what the players do but look at what the industry is doing to perpetuate these confusing messages. Every action has a consequence, even if it is small in and of itself, the bigger picture is made up and dictated by all of these individual actions. If some kid in China has braided hair and is wearing a do' rag while downloading Jay-Z MP3's and Hot Sauce clips, then the big picture of streetball is going to be changed. The actions taken by the industry make even bigger impacts to streetball. We'll explore these in the next part.

Did you ever play basketball? Or any basketball video games? Were you a fan of the Mix Tape Tour, or freestyle basketball? Or is this the first time you're hearing about it? Let me know in the comments section please. As always if you would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment