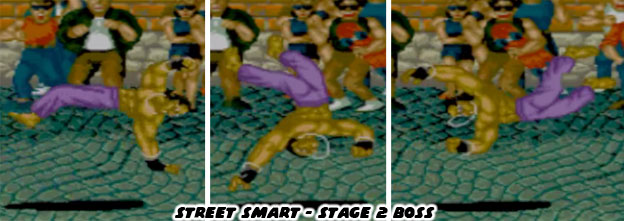

The Dictator seemed the perfect template for fighting game bosses. That was until one day Street Fighter II got an upgrade and introduced the world to the monster known as Gouki aka Akuma. The character was hidden in the game, he could only be fought after certain criteria were met by the player. The gamer could not lose any rounds and had to defeat most of their opponents with a Super Attack. It seemed like only the best players could meet these requirements. In most arcades whenever a player was about to face Gouki all of the other patrons would stop what they were doing to see the man in action. Just before the fight against the Dictator a new opponent appeared. Gouki had a move that allowed him to slide by his opponents, the Ashura Senkuu. In this case he would slide right past the player and pummel the Dictator with a flurry of strikes. Players didn't know it at the time but the attack was known as the Shun Goku Satsu, literally the Instant Hell Murder. He would then drop the defeated Dictator and turn his attention to the player and issue a challenge. It was one of the earliest cinematic experiences for the genre. This display of raw power was unnerving for the first players that reached him. Gouki had an assortment of moves that none of the other characters had. He could throw fireballs from the air, dive kick and throw opponent while leaping as well. He was absolutely relentless in battle. Unfortunate players would be dispatched by a Shun Goku Satsu. The legend of Gouki would only grow from there.

Players had no back story on the character so rumors began to circulate as to his origins. Why were some of his moves similar to Ken and Ryu? Was he the father of Ryu or was he some long-lost rival? Was he their former master? Why was he so powerful? Most important; where did he come from? The answers to these things would be revealed over time in many more Street Fighter sequels. The actual origins of Gouki were less inspiring. Capcom was asked to release upgrade after upgrade for the arcade hit. Bootleg CPS-II boards allowed cabinet owners to set up all sorts of special things that deviated from the regular gameplay. They could speed up attacks, allow players to switch characters on the fly and increase the combo system so that battles could take place mid-air. These variations of Street Fighter II often turned up in liquor stores and laundromats rather than arcades. Capcom released the Turbo and Championship Edition upgrades to arcade owners that wanted legitimate copies and not bootlegs. At the same time titles from SNK including the Art of Fighting and Fatal Fury as well as competition from the US in the form of Mortal Kombat had begun putting additional pressure on Capcom. The studio was at a crossroads. They could continue working on Street Fighter III or take some of those characters and make one final push for a SF II upgrade. Management pushed for the latter and Super Street Fighter II Turbo was born.

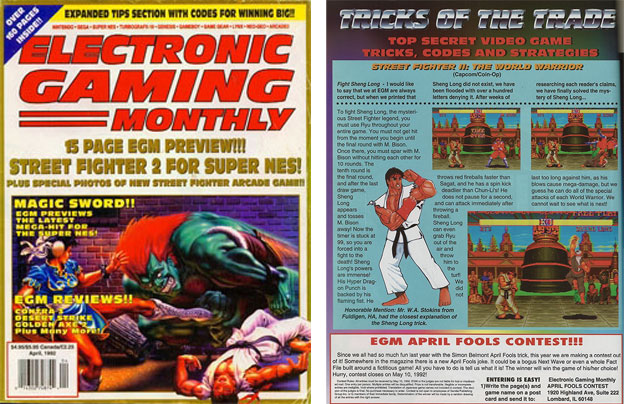

It was not enough to simply add some new moves, characters and animations to the original SF II lineup. The game needed a new boss character to go with it. Electronic Gaming Monthly had a hand in creating the Gouki myth. During one of their more elaborate April Fools jokes they created a hidden character called Sheng Long, named after the dragon punch used by Ryu. They included screenshots to help sell the character. They said that the only way to reach the true master of the game was not to lose any rounds and avoid getting hit by the Dictator until time ran out. At which point the master of Ken and Ryu would show up and beat up the Dictator. Those that didn't get the joke spent the better part of a summer trying to unlock the character. Rumors that the friend of a cousin in some unnamed arcade had seen Sheng Long in action. The myth stayed alive for years. The internet was not widespread in the early '90s so there was no way of proving if it was true or not until EGM had said something. Capcom learned about the prank and decided to put Gouki in the game using similar criteria. Unlike EGM the people at Capcom did much more than put a ponytail on Ken when they created him. They wanted players to remember this boss. In order to do that they had to make him absolutely terrifying and unlike any boss ever seen before.

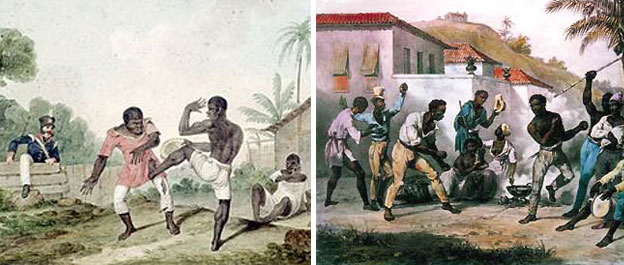

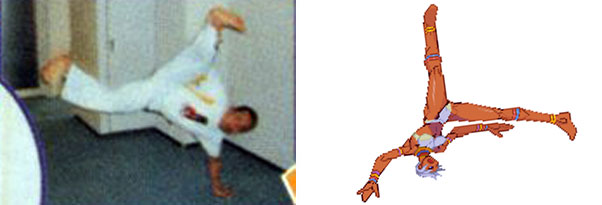

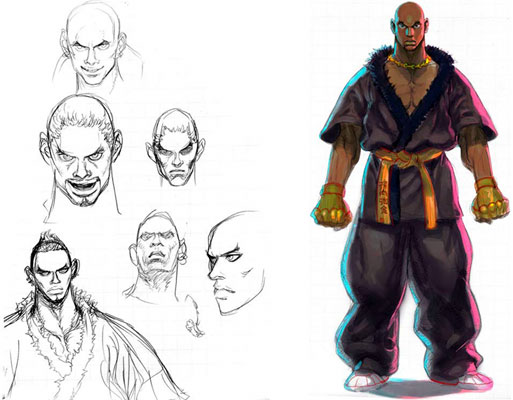

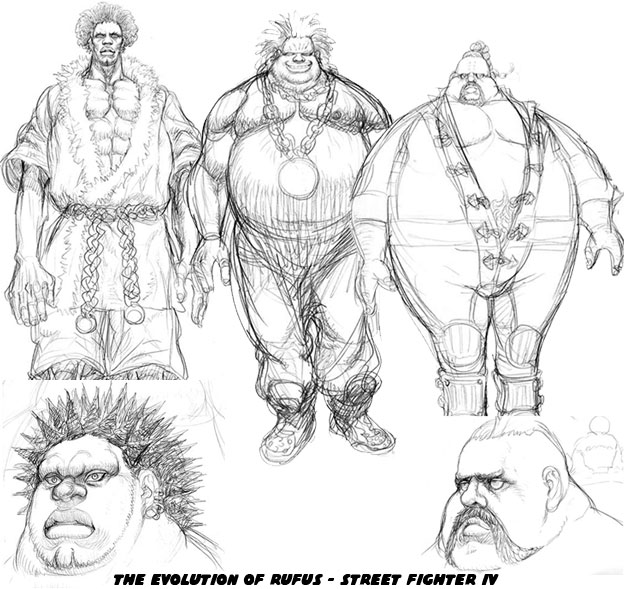

The designers at Capcom in Japan put together the definitive style guide for fighting game bosses. Actually they had done such a good job that Gouki could be considered as one of the great villains in all of game history. They started by making Gouki appear less human and more animalistic. They flattened and broadened his nose. Instead of a normal skin tone they gave him dark red, almost clay-colored skin. He wore all black and had a rope belt. His hair was crimson, spiky and tied up in the back like a crown or horns. The artists actually looked at a lion for inspiration. The king of the animals was a great template to work from. Years later the studio would revisit the design when they created Leo, the warrior featured in Red Earth / Warzard fighting game. The dark eyes, with a red glint, the sharp teeth… Gouki could hardly be considered human. This was an important trait from both a design and a gamer perspective. The physical traits were used to intimidate players. Although there were bigger characters in the game none of them had the presence of Gouki. Players were not staring down a man as much as they were staring down a beast.

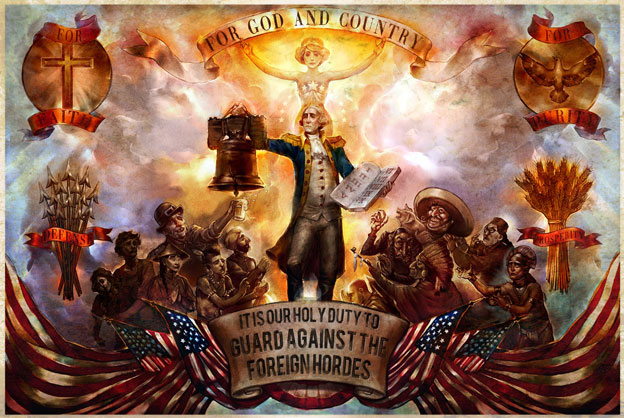

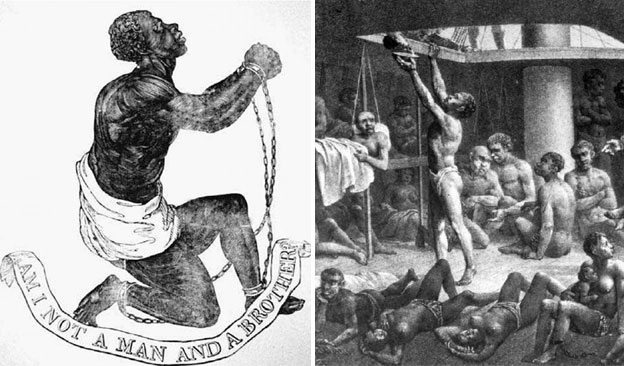

This was a fine line that Capcom was walking. The use of physical traits to make a person seem more animal than man was used in racist propaganda less than a century ago. By dehumanizing minority groups it was easier for the public to side against them and for segregational laws to be passed. In order to make players fear Gouki he also had to be dehumanized. The Dictator was an impressive boss but Gouki was the peak as far as villains went. Capcom was able to dehumanize Gouki without offending players or their sensibilities. Part of that was through the animal cues but part of it was also through spiritual and metaphysical traits. Gouki wore large wooden prayer beads around his neck. This did not make him a spiritual man but instead was a sign to demonstrate that he was a martial arts master. While most Westerners were familiar with the colored belt system used in karate Gouki had evolved well beyond that. He wore a rope instead of a colored belt. The beads were an older symbol, they were something that he had taken from his old master, a Chinese martial artist named Goutetsu. The poses and art featuring the character were pulled from ancient Chinese and Japanese mythology. The demonic protectors of the gates of Heaven and Hell were mighty warriors. They were muscular, crimson skinned, had fearsome scowls and spiky hair. The connections between Gouki and the ancient Nio were certainly more identifiable for the Asian community than the Western one.

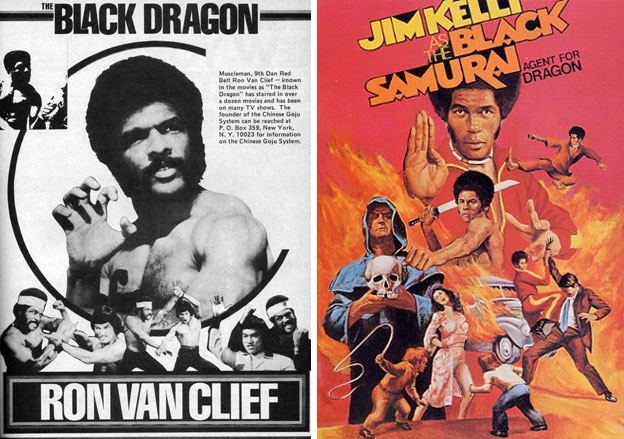

This relationship between man and demon was not lost on westerners however. His design was believable but clearly supernatural. It was the way in which the industry reinforced the myth of the supernatural karate fighter that kept audiences coming back for more. The next blog will explore a similar villain created by SNK. As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!