A blog about my interests, mainly the history of fighting games. I also talk about animation, comic books, car culture, and art. Co-host of the Pink Monorail Podcast. Contributor to MiceChat, and Jim Hill Media. Former blogger on the old 1UP community site, and Capcom-Unity as well.

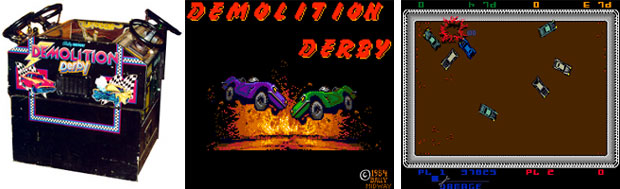

Demolition Derby released in 1984 by Bally Midway was probably the most overlooked arcade game that I played. It was liked only slightly more than Stocker in the arcades. The game was in an overhead format and, like Hot Rod, played on a tabletop cabinet with multiple controllers. Demolition derby is an American institution. While this nation prides itself on creating hot rod culture, muscle cars and a great racing legacy, we are also known to go into fits of excess and nonsense. Demolition derby was the latter. The point of the game, just like the actual sport, was to smash into your opponents car and disable them. It's the car equivalent of the gladiator, the last one running was the winner.

The cars weren't ever new, most were fixed-up from a junkyard just a day or two before the derby. They were big, ugly, boxy American cars with poor steering and solid motors. Their appearance being part of their charm. The derbies themselves were slow and methodical. Like watching two grizzled boxing veterans fighting on the last round. Neither was pretty and neither had anything left to give. The best they could do was trade hits until one went down. The cars line in the derby against each other, as many as a dozen at a time, like enormous football players. The drivers usually went in reverse so as not to damage the engine and steering.

All of this carnage and brutality was recreated in the Bally Midway game. Players would last longer if they went in reverse and aimed for their opponents front. Wrenches could be picked up along the way to give cars more life. Good opponents, or the enemy AI on latter levels, could make the game grind on for a while. The winner was the last car moving. I kind of miss the reckless experience of crashing into cars in that format. Thankfully there was a modern series that combined the elements of Demolition Derby with the high speed hijinks of Chase H.Q.

Criterion Games smash-hit (no pun intended) driving game Burnout made its debut in 2002. After a few sequels, the addition of downloadable content and a global fan base it is safe to say that the series is going to be around for a long while. Burnout was one of those titles that made me glad my brother got an Xbox 360. The slow and ugly cars from Demolition Derby were nowhere to be found here. The Burnout cars were high speed racers very much based on legendary vehicles, sporty hot rods, muscle cars, race cars and trucks from real life. All of them were changed just enough so that no major auto maker, or movie studio, had to be compensated.

Burnout succeeded because it tapped into several themes of the racing genre often overlooked by publishers. It was an arcade racing experience at the core, not a traditional console racer. The sense of speed was very dramatic, the flowing track layouts helped bring that experience home. Cars flew all over the levels and took turns and jumps without losing much, if any, momentum. Players were never bogged down with a sim experience. There were no gear ratios, transmission or tire selections to worry about. The player simply had to point the car in a direction and then hammer on the gas. Any secrets, shortcuts or unlocks they found along the way to first place were a bonus.

The game could be very forgiving to those that never grew up on arcade racers. It was written for the generation that grew up on the gamepad rather than the steering wheel. The purpose of the main races was not only to come in first but to also damage the opposition as much as possible. You could run rivals into oncoming traffic, push them off bridges or slam into them demolition derby style. The experience of racing was similar to Chase H.Q., only without the badge. Everyone in the race deserved to be taken down. I have yet to come across a player that didn't revel in the experience that Burnout offered. When you added the different modes and online ability of the recent versions then you can see how gamers, and not solely racing fans, would want this title in their collection.

As much fun as Burnout was there still is only one driver that I enjoyed far more than it. A game whose content offered even more action, violence and impossible stunts than Burnout, Demolition Derby, Chase H.Q. and Mad Gear combined. I hope to see you back for that, oh, make sure you buckle your seat belts.

In 1985 Jaleco released the puzzle racer City Connection. It was a familiar maze type game in which you were supposed to color all of the pavement in one color before proceeding to the next stage. Along the way you were supposed to avoid the cops and try not running over a cat... To help get you out of a jam you could throw oil cans at the cops to cause them to spin out. Simple and to the point.

What caught my attention was the presentation of this title. Unlike Rally X this was not an overhead game but a side-scroller. The graphics were very bright and detailed. The backgrounds and music would change on every stage, taking the car all around the world. The freeways that player painted were multi-tiered. The car had the ability to jump up and down these different tiers. It was the jumping element that I found awesome. The car could jump on command for no other reason than "just because". It's compact, stylized body, looked very much like a Choro Q made these animations really stand out.

However the car in City Connection couldn't touch any obstacle without losing a life. It was far too fragile for my tastes. But I was intrigued with the leaping ability and how it could be used in a racing game. The one that had gotten the formula right had debuted a few years prior.

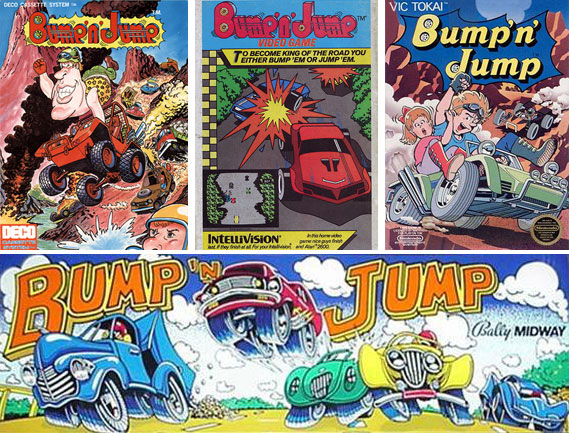

Bump 'n Jump (BnJ), Burnin' Rubber to my pals overseas was made by Data East in 1982 but released by Bally Midway here. It was an overhead racer, comparable to Monaco GP. However the rival cars in this game were far more stylized and aggressive. The player would have to fight for position and get a bonus for running an opponent into a wall. The cars were really odd looking, blocky and ugly and the only time you saw any detail was when the player car jumped. It was the jumping itself that really sold the experience. Players could move left and right mid-flight and land squarely on an opponent. Smashing them in the process and gaining a speed boost. Just like City Connection this feature never had to be explained, the car jumped as part of the game mechanic and it was fantastic.

Players had to mind the courses as the walls of the tracks would zig and zag, pinching groups of rivals together and blocking the path. The car couldn't jump at any time either. It had to be going above a certain speed or else the jump button wouldn't register. Some tracks constricted, went to dead ends or had drop offs into the ocean. Players had to become masters of timing. They had to read the course, their opponents and know when to jump and where to stick their landings. Sometimes the landing was on a narrow piece of road in the middle of the ocean, from which the player had to leap off of right away.

The play, design and music were all memorable but what I always admired most about this game were the impressions it gave different artists and publishers. No two studios interpreted the game exactly the same. How did the car really look, who was the driver, what were the rivals? What was the plot of the game, if it even had one? Did any of this even matter? Or was it a sign of the early arcade experience, games existed for the sake of games and players made up the connections as they went along.

Bump 'n Jump appeared on several consoles over the years, many often much better-looking than the arcade original. The NES version was actually very impressive as it added a plot and purpose to the racer and opponents. The elements introduced in Bump 'n Jump would continue on through rival titles.

A year after Bump 'n Jump Sega released an isometric racing puzzle game called Up'n Down. This game featured a VW Beetle riding on a single lane road collecting colored flags. Other cars and trucks would be running along or against you trying to block your path or crash into you. The track continuously scrolled on a loop pattern until all of the colored flags had been picked up. The game was actually tricky for a puzzle racer. It was the first isometric game that I remember giving the cars a sense of mass. The beetle would lose momentum as climbing a steep or long gradient. Conversely downhill sections would provide a speed boost. The car could even go in reverse to collect a flag that lay around the corner. There weren't many games at the time where going in reverse was an option. The jump featured in the game allowed you to not only clear opponents but also sections of tracks. All the while you had to be mindful of rivals coming from ahead and behind as well as sections of track with gradients as opponents would sometimes also lose momentum and come rolling backwards into your path.

Sadly Up 'n Down didn't break enough ground to keep me interested. The wide open tracks of Bump 'n Jump and use of jumping were much more fluid by comparison. There was one game in the arcades that updated the idea of Bump 'n Jump, or ripped it off depending on your point of view.

In 1989 Capcom released Mad Gear. It was an atmospheric future racer in a familiar overhead setting as BnJ. It also featured similar mechanics involved with jumping, needing speed in order to jump and landing on opponents for a score booster. The game had lots of interesting details as tracks and accompanying music changed themes in each stage. Most of these tracks were floating a mile or so above the ground, how or why these roads were built never really mattered. They just looked cool as they ran underneath dinosaur bones or between Mayan ruins. These tracks predated the Sega racers by years. Here's a bit of trivia for you, the gang in the Final Fight series was named after this racer.

Opponents ranged from crazy bikers that would jump onto your car to massive segmented trailers which behaved like land trains. From time to time a helicopter would even fly overhead dropping bombs onto the track, and unlike Spy Hunter your car had nothing but a jump in its arsenal. Keeping an eye on the tracks and opponents was part of the challenge, as was finding fuel. The player was given a choice between three cars, each with their own strengths and weaknesses, the diesel truck did better on fuel but ran slower, the F-1 racer clipped along quickly but ate gas just as fast. The main car, the Mad Gear, was the balanced ride. Players that managed to complete the game on one quarter, and that was possible if the dip switches were set to normal, were rewarded with a free game and could choose to race in a different car. This second play through gave a definite ending where the car would thank you for the experience. I thought it was a nice detail that helped frame the universe the game was set in. The car was the partner in the race rather than a human navigator. An arcade version of KITT, complete with turbo boost jumping action.

I could understand that many arcade gamers couldn't get behind racing games where the car did fantastic things. However there was something about using the car as a weapon that intrigued them. Unlike games where the car was loaded with weapons and behaved like a FPS character, the car could still move and feel like a car but become the ultimate blunt force weapon. Come back next time to see the best drivers that kept that in mind.

Japan gave me some memorable driving experiences in the arcade. As I got older it became more and more obvious to me that the developers overseas didn't have the same points of reference as developers over here did. Their early entries into the racing genre were sometimes very questionable. In the same year that Sega released the original Monaco GP (1980) Namco had developed another car-based title. This wasn't a racing game as much as it was a puzzle game. These types of games used joysticks and buttons rather than steering wheels and pedals.

Bally and Midway like to take a lot of credit for Namco's Rally X. But we know that the developers were Japanese and looking for a way to expand the appeal of the maze game. Namco's Pac Man was a red-hot commodity so of course they'd try new things in the same format. Rally X was very much Pac Man for car fans. The cars didn't look like rally machines either but instead dune buggies. You were in control of one from an overhead perspective trying to collect all the flags on each map. All the while avoiding obstacles and opponents. To help throw your enemies off course you could use a smoke screen. There were only two things I liked about the game, the cartoonish cabinet art and the ability to put up smoke screens. Maze games never really appealed to me.

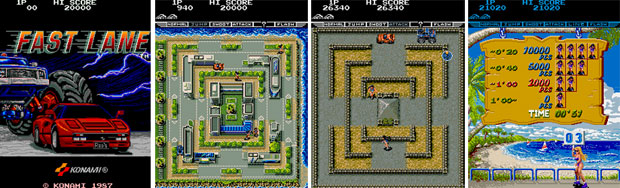

Rally X must have had its following because the game has been ported to many consoles and has ended up on a couple of "greatest hits" compilations. Most recently as an updated version in the Namco Museum Remix for the Wii. However the car maze game wouldn't end with Rally X. Seven years later Konami would introduce the world the the nonsensical Fast Lane.

By 1987 racing games were becoming a genre that all publishers had to be good at making. Failure to make a memorable racing experience meant that you were behind the curve. That was the case with Fast Lane. It was a maze game similar to Rally X. Except instead of being chased by some buggies you were instead chased by one or two monster trucks. The purpose of the game was to drive over the lanes covered in dirt while avoiding the trucks. Clearing a level of all the debris would end that stage. Monster trucks sometimes dumped dirt back on the road. Power-ups could be collected by girls inline skating around the maze. These power-ups could be used to jump over the monster trucks, or blow them up.

Seriously folks I'm not making this stuff up. What the girls had to do with the game, why the monster trucks had to get blown up and why the red sports car had to clear the streets is completely beyond me. It's as if somebody in Japan said let's make a maze racer with things that Americans love. Almost 20 years later I still get the feeling that Japan sometimes releases titles based on stereotype than insight. Sega's Hummer and Race TV anyone?

Between the years of Rally X and Fast Lane Japan would actually make some major milestones to the racing genre. A couple were puzzle games but they got us thinking about the car as something more than a mode of transportation. Instead the car could be given a personality and made into the star. I hope to see you back here to find out what games I'm talking about.

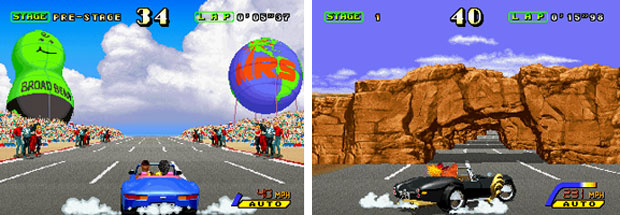

OutRun is an arcade legend, on par with the biggest names I've featured yet on the blog, and possibly the biggest title I'll be naming in the series. It was an easily accessible racing game not built for the sim community. It was an arcade racer through and through, whose bright graphics, multiple tracks and questionable physics appealed to everyone. My favorite version of the game was not the original title, but it's spiritual successor Outrunners.

Both games more or less played the same. You were driving a supercar in a trans-global race. This was one of the first racers to use gradations in the game rather than have tracks be completely flat. Drivers would take hills and not be able to see the path ahead, that level of uncertainty was exhilarating especially while doing well over 100 MPH. The drifting was subtle in OutRun but full out in Outrunners. Cars were large and cartoonish and unlike the other racing games of the time were not hung up on realism. It was the fantasy aspect that I think pulled most gamers to this title. If you were traveling top speed in OutRun and ran into a wall then the driver and passenger would get launched out of the car as it tumbled and land back inside by unseen forces. Unlike Pole Position where the slightest bump would cause your car to explode the racing featured in OutRun was more about the experience of driving and having a good time. Cars could jostle for position and trade paint without fear of game-ending explosions.

The timed courses were laid out with multiple paths. At the end of each checkpoint you were presented with a fork in the road. This opened up the racing experience in all sorts of ways. Players were no longer limited to replay the same tracks over and over as they could experiment and go for bigger scores and new experiences on each play through. Given a choice was a rare commodity in racing. The driving experience had become an unspoken narrative. Even though there was never a break in the action visual clues let us know which part of the world the stage was set in. Caricatured parts of New York, Paris and Egypt all popped up. It was a celebration of the international racing brotherhood. Yu Suzuki designed the original experience around the Ferrari Testarossa. It was an exotic car that lent itself to this type of experience. The name Ferrari alone conjures up images of excess, luxury and horsepower, it was made downright mythological by Suzuki. However as much as I liked cars I was never fond of Suzuki's obsession with the Ferrari. I felt that the world of cars was too big to be hung up on only one ride.

Outrunners was very much a second-coming of OutRun. The graphics of the '92 release were far superior to the original from '86. This game even featured the familiar Testarossa and her driver and passenger. Joining them were all sorts of other drivers and cars in the competition, each designed for a certain type of car fan. From an exotic Shelby Cobra-like car to a Volkswagen Beetle and even a big pink Cadillac. This game simply expanded on all of the things that made the original OutRun so much fun. However Outrunners was developed by Sega's AM1, not Suzuki's AM2. To many it could not compare to the original. Say what they will but I loved it.

Outrunners was beautiful. The cars each handled slightly differently, as would be expected. Discovering the nuances of each ride was what kept me coming back. As was the breakneck speed of the title. Sliding the car completely sideway through a series of stone archways, "threading the needle" in the most awesome sense of the word or dipping past the checkpoint just ahead of my brothers and friends as we played this in the arcade. This game was responsible for plenty of great memories in the 90's. The more that played on the linked cabinets the better. The details of a radio built into each cabinet was nice. Each station played an updated version of the classic OutRun music and players were free to switch stations on the fly. The titles would scroll by the LCD of the dashboard. How many arcade games ever went that extra mile?

The official sequel wouldn't come out until 2003. By the time of OutRun 2 AM2 had grown by leaps and bounds, learning everything they could from their polygon legacy. It was a fun game that returned the series to its roots. All of the cars in the game were Ferraris and the graphics were stunning. I couldn't help but imagine that this was the type of experience that Suzuki had dreamed about giving arcade-goers a generation ago, now he finally had arcade machines and consoles with enough processing power to deliver it. As it turned out the Xbox title was not the last we would see of this classic racer. Sega is putting their finishing touches on OutRun Online Arcade. Fans around the world can't wait to relive all those great memories through the classic experience and even updated versions of their favorite OutRun songs.

While OutRun wasn't my favorite Sega racer ever it was still pretty damn good. There was a studio out there to make an arcade game that was every bit as memorable as the best Sega racers, including OutRun. However their name wasn't Namco and this studio was never known for making racers at all. Come back next time to see what I'm talking about.

When people think of great arcade racing experiences they can usually name a handful studios that have contributed the lions share of the memories. Sega, Namco, Atari and Midway are usually the studios at the top. Nobody would have thought to rank Konami with those guys. Not that Konami was a stranger to the arcade racer but their showings were few and far between. The only other game I've mentioned from them so far was the dizzying Chequered Flag. However my opinion of the publisher changed in 1996. Their first memorable polygon racer came out at the time when Sega Rally and Daytona USA were still hot in the arcades. GTI Club Rally Côte d’Azur broke everything we knew, or thought we knew about arcade racing. It was a rally game as the name suggests, set in the lovely Côte d’Azur, better known here as the French Riviera. It's the type of location most of us wouldn't mind moving to and spending our time lazying away by the coast. The rallying that goes on here features the compact yet still sporty GTI (gran turismo injection) class of cars. The figurehead being the ever-loving fiery little powerhouse Mini Cooper.

The courses were all set in the same town. Konami rendered a highly-detailed town, complete with tunnels, bridges, a coastline and hill rather than make a few tracks like rival Sega. The courses were more or less open so you could take the shortest possible route to the checkpoints if you wanted. It was my first exposure to sandbox racing and I was hooked! Up until then I had been taught by other arcade games to follow the other racers, look for an opening and pass them on a turn. This time around if you spotted a line through some narrow streets, that ended up knocking over a few tables, but managed to shave seconds off your time then go for it! The tracks and their respective shortcuts took players all over the little town, jumping like madmen in the tiny cars over hills and down sidewalks. There were even train tracks crossing one of the roads so making an attempt to cut off a speeding train in the middle of the rally to save time became very tempting! The game was frenetic and left little room for error. Given the size of the racers themselves that was saying a lot!

To help supplement the tracks the game also featured multiplayer modes like Bomb Tag (last person with the bomb explodes) and car soccer. Trust me, it was more fun than it sounded. I only played GTI Club a handful of times because the only arcade that had it was far from home. Those few times that I played it I learned a few things. The game was more fun with a friend and it certainly wasn't an arcade racer for everyone. The tight control and manic pace of the game would break any casual gamer. This game wasn't even meant for most arcade racers due to it's learning curve. It was meant for die-hard rally nuts and those looking for something new.

Konami delivered on both fronts and continues to do so as an exclusive download for the PS3. If you fancy yourself a good driver and enjoy a good multiplayer experience then check it out. It was an example of the unique contribution that Japan gave the racer. However in the early days of arcade driving Japan was, wait for it, way off course. Sorry, I couldn't resist. Next time we'll look at some of Japan's more unique and one lamentable Konami entry to in the arcade.

The Daytona USA series is an odd duck among racers. It, like Super GT and the other Sega classics, is either loved or loathed by racing fans. Feelings about Daytona USA are much stronger than any other racer by Yu Suzuki, or to be more accurate as Alex aka FerrarimanF355 pointed out to me the director for many of the Sega racers including Daytona USA was Toshihiro Nagosh. The reasons for which might come down to what Japan doesn't understand about Western racing culture. Those that dislike Daytona USA would argue that the title was unabashedly Japanese in scope, it succeeds by being an ignorant arcade statement about stock cars and western racing. Those critics might be right.

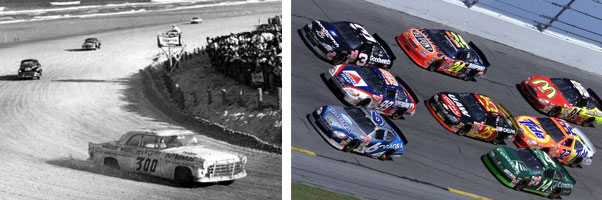

The track for which the game is named is based on the legendary Daytona International track in Florida. It was among the oldest of tracks in a fledgling NASCAR circuit. Back in the 50's the track was right on the beach. Massive production cars would tear up the sand, just a few feet from brave, or crazy spectators. These cars were stock in appearance but everything under the sheet metal was anything but. Even today the stock cars carry the large proportions granted by their originators. The current Daytona track is built right over that original track in the sand. It is as beloved a racing course as any other track in the world. Only a few things in Daytona USA would even draw comparisons to the real deal.

The original beginner track in Daytona USA was a three turn oval but it looked nothing like the real course. It was far more fantastic in origin. Snow capped mountains loomed in the background and a rocky cliff was etched with the visage of Sonic the Hedgehog. This track, like every track AM2 was famous for, excelled in the spectacle. The layout defied logic but was an amazing sight to behold. Virtual architecture that rivaled the greatest wonders of the world. Courses that snaked through a canyon, inches from NYC skyscrapers or rumbled down the middle of an amusement park. These were the best tracks I had ever experienced but at the same time the name of the game and style of car had rubbed me the wrong way.

I grew up on racing. Being a fan of every type of circuit and style imaginable. You can guess that my feelings toward a Sega game named Daytona would be mixed. The game featured the familiar boxy cars from the NASCAR circuit but they looked a little odd. This was not a licensed stock car racer so the cars had to give a familiar vibe by their shape and bright paint job. However these things were done from a Japanese perspective. Japan had more experience with GT and even F-1 racing. Those were cars that were created with racing in mind, rather than regular cars turned into racers by mechanics. The Japanese interpretation of the stock car was, for lack of a better word, dubious. The stock car was a foreign breed, a big and brutish American racer. It was unrefined and garish, much too swollen for racing, brightly painted in contrasting colors, a rolling reflection of the loud gaijin and beer swilling rednecks that adored driving 500 miles in a circle. The cars featured in Daytona USA reflected this brutal opinion.

The cars were more or less shaped like stock cars but with fanciful names and questionably-designed logos. Undoubtedly fruity names to get Japanese gamers interested in these brutes. The game was made to bring American gamers to the arcade, but to make it more appealing to the rest of the world it made many concessions to the car design and gameplay. The Daytona series played just like the previous Sega racers. The only way to beat the courses was to drift, or power slide, around every corner. Each successive pass would "slingshot" you past opponents. The sight of massive blocky cars sliding around corners, in the way that was previously reserved for lightweight Ferraris, was too much to behold. The secret cars were anything but more stockers, they were instead crazy-named cars that players could unlock for added replay value. These odd cars were a jab at the roster of racing machines featured in Namco's rival Ridge Racer. I was unimpressed with the effort and slightly disappointed with how Japan was treating the stock car name.

The game was beautiful and is still fun to play, if you could get past the suspension of disbelief. Daytona USA 2 looked amazing on an updated version of the Model 3 board. It's tracks were among the best ever, even trumping the eye candy featured in Super GT.

Unlike Super GT the consoles and PC saw several versions of the Daytona racer released. The most recent appearance of Daytona USA also happens to be the most memorable. The great Daytona USA 2 tracks make an appearance as a single interconnected track in OutRun 2's bonus stage. Making it a definite must-get for racing game fans. Did you know that the things that got NASCAR purists riled up with Daytona USA worked in a different breed of racer? Sega's obsession with drifting would finally make an appropriate appearance, but not in a Yu Suzuki game. Find out which game I'm talking about tomorrow!

Scud Race or Super GT as it was known over here was the pinnacle of AM2's arcade racing legacy. Sega golden boy Yu Suzuki had delivered the ultimate supercar experience. It had taken him almost 10 years to reach this point. The advances he had made to arcade racing along the way were unparalleled. Very few studios could have claimed to have developed a better series and no producer could have claimed a better team.

Scud Race was an arcade racer built around the GT class of cars. The GT in the title means Gran Turismo, or Grand Touring. It was a term that denoted mid-sized cars with big engines. In europe this breed became sports cars, in the US they were the forefathers of muscle cars. These were production cars that were designed with track racing in mind rather than taking the kids to school. The ones featured in Super GT represented the highest-end sports cars from around the world; the Porsche 911 GT2, Dodge Viper GTS-R, Ferrari F40 GTE and McLaren F1 GTR. These were specially modified racing versions of the production cars. The ones that every young boy dreams about owning some day. The cars for lottery winners and Hollywood jerks. Rather than let us lowly gamers dream about what it must feel like to handle these magnificent beasts Suzuki handed us the keys and let us go to town.

Super GT, like all of the Suzuki racing games, was about racing in style. His games had never been racing sims. The sim wasn't really what brought people into arcades. An arcade racer had to grab the player by the short hairs and go full throttle until the end. The illusion of speed, sliding inches around an opponent, flying dangerously close to the wall and being on the verge of a wreck each and every lap was what people craved. Suzuki, and the AM2 team at Sega excelled in giving us more of everything, more speed, more cars and more tracks than any other racer to-date. Scud Race even had an extra secret in the arcade. In Scud Race Plus there was an oval track presented in the middle of a house. The cars were all the scale of remote control racers on that track. If players put in a code the four cars could be substituted for four toys, well, three tin toys and one cat. The windows on the toy bus was plastered with pictures of AM2 employees. For the casual racing fan this game was an adrenaline overdose. For die-hard car fans this was heaven, at only 50¢ per play.

Yu Suzuki, like the best Japanese game designers, managed to turn his hobbies and interests into great games. He two automobile fetishes that he loved sharing. The first was his passion for the Ferrari and the second was his fascination with drifting. Each and every time Suzuki helmed a racer they seemed to have at least one of those things in it, if not both. The use of the drift in the Sega game polarizes most racing fans. They either loved it or hated it, never anything in between. Cars could careen around corners going completely sideways and somehow gain momentum this way, defying all logic as well as the laws of physics. Drivers that learned how to slide could find the best lines on a course. It was the only way to beat tracks and exactly how Suzuki had meant for them to enjoy the experience.

Of course of of this sliding wouldn't have amounted to much on any normal track. The true genius of Suzuki lay in his track designs. Courses that offered challenging lines and flat out speed. Speed that was exaggerated in the proportions and details of the crisp Model 3 graphics. Speed that was accented in hidden temples, awesome skyscrapers, opulent palaces, aquariums and wondrous freeways that flowed through the world. There have been thousands of incredible worlds presented to gamers for decades, some flat and some fleshed out. If you were to ask a racing fan which world they wished were real, which world they could inhabit then they'd probably say a Sega one.

Sadly Super GT was never ported to consoles, but the experience was not forgotten. The arcade courses were stitched together in a single flowing masterpiece as part of OutRun 2's bonus stage. Purists would say that the game following Super GT was the last great Sega arcade racer. That might indeed be true, please come back tomorrow to find out what that was.

I bet many of you are wondering when, or if I'll ever talk about the Micro Machines gaming series. Some on 1UP probably remember that game better than RC Pro Am or any of the arcade title's I've mentioned. Sorry but Micro Machines was one series that didn't make the cut. Neither did any of the Hot Wheel titles. I will say that some of the Micro Machine and Hot Wheel games were good times but cannot compare to the series I feature today.

Choro Q got started as a line of toy cars from Takara. Around the world these were known as Penny Racers. Cute, super-deformed cars with pull back motors. Just about every make and model of car, truck, scooter, wagon, what-have-you was made in Choro Q form. These were done at least a decade before the term "super deformed" was even coined. The artistic stylings of those cars which would pop up in Japanese racers for the next 30 years. In particular as the cabinet art that I really admired in Sega's Hot Rod. Even though Japan never had a hot rod renaissance, CARtoons magazine or Ed Roth, they still managed to make the car something unique and memorable. To give it life, and in the case of Choro Q, make them magical.

The Choro Q game series has been around for years. The length and depth of the gameplay going far beyond the Micro Machine series. The Choro Q's themselves were sentient vehicles. They talked, pantomimed and lead very human lives. The games were not solely about racing but an adventure RPG. There were tons of mini games and missions to make each play through interesting. The main car, you, would go on adventures, complete missions and become weaved into a plot. The moral for most Choro Q games was about self discovery rather than accomplishing a 1st place ranking. The other vehicles you met on your journey represented the range of the human experience. Some were funny, some sad and some very angry. As melancholy as the game could get it was always tempered with a message that life must go on. It is up to the player to make the world a better place, even in their absence.

Animal Crossing gets a lot of love in the gaming community for covering a lot of this familiar ground. Gamers like myself find it hard to emote through anthropomorphic animals and super deformed kids, however we can identify through the Choro Q vehicles. It must be a guy thing. As I had hinted to 1UPper Erin, the Choro Q games is very much the Animal Crossing experience with cars. For those of us that adore cars in every form could really get the game on every level, but especially on the racing format.

The game was targeted for boys but the challenge on the races was serious enough for older gamers as well. Some of the races are real nail biters, coming down to the last turn or a final gear. The tracks themselves ran through every possible format and added a dozen new concepts to the mix. Racing games had touched just about every possibility, few games have managed to do one format well, let alone many formats equally well and, more importantly, fun. Choro Q featured traditional circuits. Oval racing, road racing, off road racing and rally tracks. Where they really shone were in their hybrid and original courses. Worlds where the race was part on a mountain track and part of a downhill skiing course, or inside a gigantic computer, an enormous underwater cave or even on another planet. Even Sega was hard-pressed to invent tracks with as much imagination as some of the Choro Q courses. These courses all required their own strategies and special equipment if you hoped to stand a chance against the ruthless AI.

Of course players could expect to earn money and buy upgrades for their cars. The game had a very imaginative way of handling upgrades. Parts could be added to the car to make them perform better, including all sorts of silly things like a rack for camping gear and a propeller for chopping through the water. Bodies, tires and anything else that you could imagine could swapped out and painted in infinite combinations. Layered over the entire game were all sorts of whimsical songs. Ranging from rock to blues, dance and electronica, there was something for everyone in the Choro Q games. Matt did the ChoroQ review right here on 1UP. The Atlus release for the PS2 is worth checking out especially for those that are fans of an amazing racing experience.

Choro Q was great, but was it the best racing experience ever? Who would lay claim to that legacy? I'm pretty sure you know the answer already but bear with me as we take a look at the best that Sega had to offer on the next blog.