A blog about my interests, mainly the history of fighting games. I also talk about animation, comic books, car culture, and art. Co-host of the Pink Monorail Podcast. Contributor to MiceChat, and Jim Hill Media. Former blogger on the old 1UP community site, and Capcom-Unity as well.

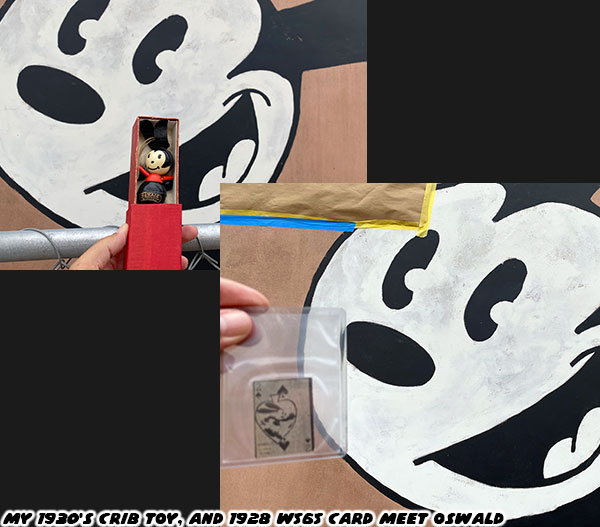

Warren Spector can't stop looking at my Oswald figure during his Epic Mickey presentation.

The evolution of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, part 3…

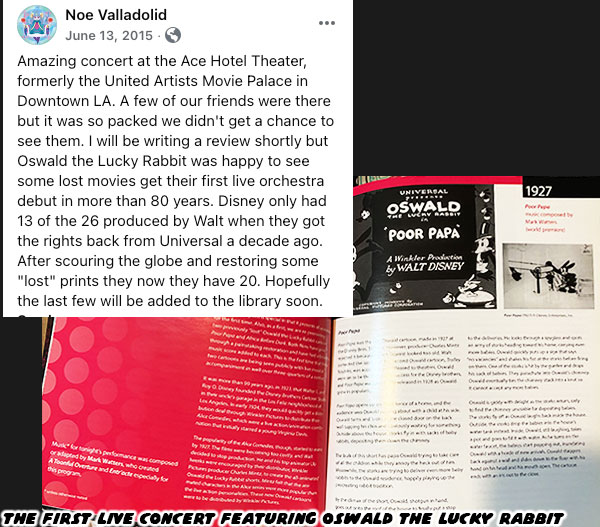

Warren Spector's Oswald crib toy next to my own.

The evolution of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, part 5…

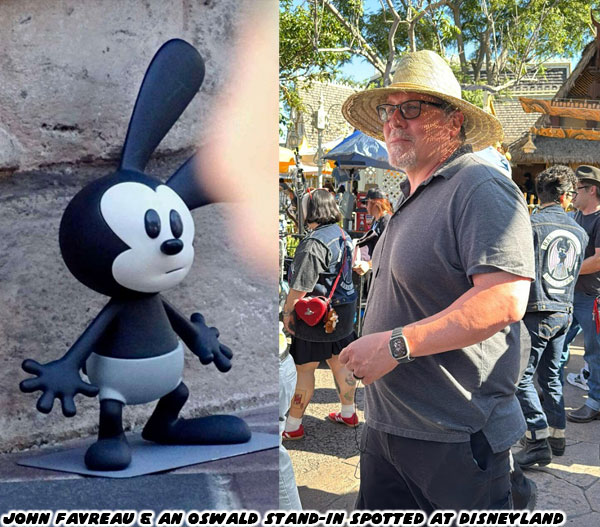

Meeting Disney animator / art director / toy designer Tara Billinger at Oswald's debut in Disney's California Adventure.

The evolution of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, final part…Hello friends, I have finished my Epic Mickey 2 review for JimHillMedia.com. I'm not certain when it will be posted or how much will be edited but here is the original draft for you to look at.

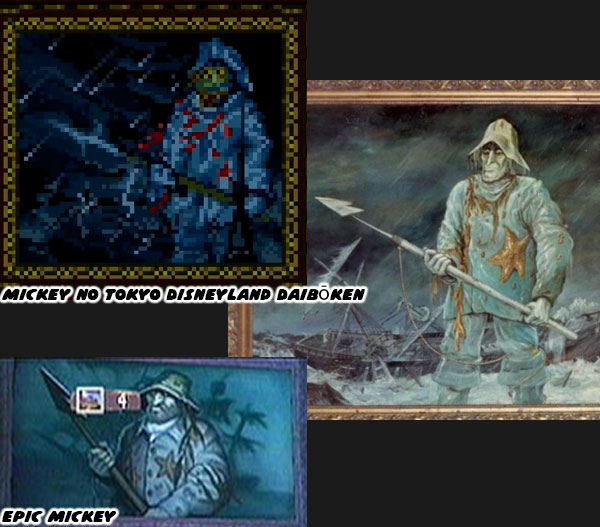

Epic Mickey 2 the Power of Two (EM2) is out now on multiple consoles including the Xbox 360, Playstation 3, Wii and Wii U. The game deserves special consideration for readers of JHM because it is layered with several generations worth of material from the Disney Archives, theme parks and film library. The world of Epic Mickey, or "Wasteland" is so saturated with history that it could catch trivia specialists flat-footed. Warren Spector, lifelong Disney fan and creator of the game had said at the San Diego Comic Con that he wanted to create a world with substance. He did not want to have gamers dig underneath the surface and discover that the Wasteland was like other games. His studio Junction Point succeeded in doing just that. In some areas of the game when Mickey Mouse dissolves the walls and floors of the world players can actually see the blueprints. The grey paper of the imagination with penciled out blue lines created by the great architect Yen Sid himself.

I've spent the past two weeks with fellow gamer Alice Hill going over the game on multiple consoles. The game has average difficulty for seasoned players but is moderately difficult for younger gamers. The main portion of the game is long but can still be beaten over the course of a weekend by experienced players. In order to get the full experience however a player has to explore every inch of the Wasteland, collect hidden items and accept side-mission that enhance the story and extend the gameplay to dozens of hours. The best way that Alice and I could review this game was by playing it on the different platforms in single and multiplayer modes and trying different options and paths. If you are interested in purchasing the game and do not want to read the spoilers then here is a one sentence review… Epic Mickey 2 is a good game but its faults prevent it from reaching true greatness. For those that want to know how we came to that conclusion please keep reading.

The camera was a major sticking point in the original game, the new camera system is much more user friendly, it follows the action better and can be moved with more precision. The camera and control really shine on the PS3 and Xbox 360 using the regular controllers. It was still a chore to use motion-based controllers in the game, and doubly so when in 2-player mode. The limited screen space and drawbacks of the motion controller were apparent when playing on the Wii and PS Move. We constantly had to keep realigning the camera to line up our targets, not to mention it was harder to perform double team moves on the Wii than the other consoles. Alice and I would recommend getting the sequel on a different console if available. Those that do have the Wii can at least play using the cool new light-up peripherals, a paint brush and remote control available for Mickey and Oswald respectively.

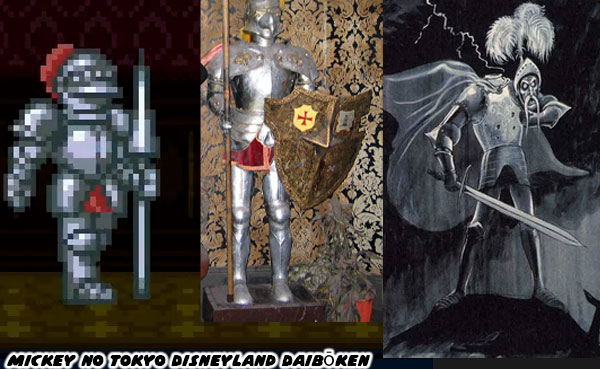

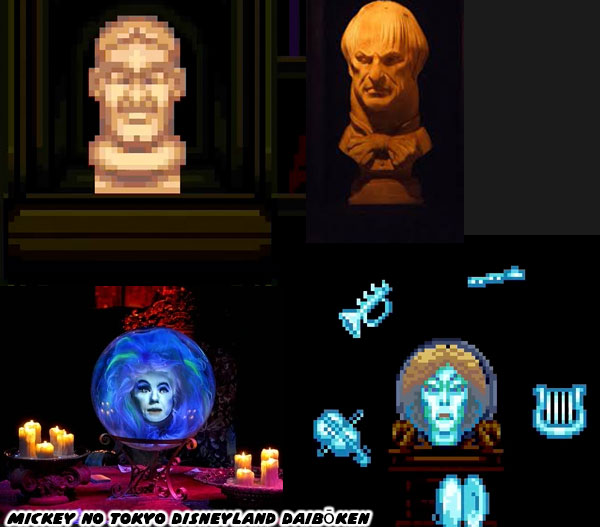

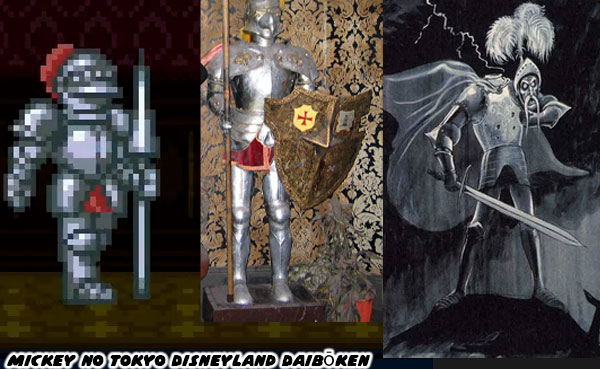

Players could travel from land to land using film projectors. The side-scrolling levels used the setting of a classic Disney film and allowed both Oswald and Mickey to explore, interact and even combine resources to get through the stage. The projectors were featured in the original game as well and contained some of the most memorable experiences. Some of the sequences in EM2 include the Old Mill, Night on Bald Mountain, the Skeleton Dance, Music Land and Building a Building. A second side-scrolling component has also been added. Mickey and Oswald can now navigate the Dahl Engineering Corridors or D.E.C., a series of underground tunnels that connect the remote areas of the Wasteland. The tunnels were named after Gremlins creator Roald Dahl but based on the Utilidoors from Walt Disney World. Each D.E.C. is made up of junk from the Wasteland, of course junk to the residents are actual antiques and merchandise from company history. Look carefully for a tape, doll or record that you might have in your collection!

This game also features actual voices for the main and supporting characters instead of the text boxes and generic grumbles used in the original. Veterans Bill Farmer (Goofy), Tony Anselmo (Donald Duck), Tress MacNeille (Daisy) and Jim Cummings (Pete) are joined by Bret Iwan the new voice of Mickey, Dave Wittenberg as the Mad Doctor, Frank Welker as Oswald and Cary Elwes as Gus the Gremlin. The supporting cast made up of Gremlins and forgotten monochromatic characters also have their own unique voices. Most blended well with the main characters. The opponents consisted of Blotlings, Beetleworx and Blotworx. Those original creations were made of animated ink blots, machines or a combination of the two. They did not have any voices per-say, mostly grunts or screams. Three additional classic animated characters appear in game if a player searches high and low for them.

The greatness that Junction Point was going after began to break down when we stopped watching, stopped looking at the details and started playing. Epic Mickey was promoted as the first gaming musical. The plot was all told through song so technically Disney was right. However the Mad Doctor had all of the singing parts with one line reserved for Oswald. The gravely voice did nothing to make the character sympathetic or pull on any nostalgia strings. Imagine seeing the Little Mermaid but only Scuttle the seagull could sing the parts. It was an odd decision considering that the Mad Doctor was used only once by Disney and was allowed to fall into public domain. None of the songs were truly memorable which was odd considering that the music was written by James Dooley. The television and movie composer wrote an amazing score for the first game, X-Play deemed it the best Soundtrack in 2010. Disney never released a physical album of the first game but did make the music available via iTunes. Many players reported crying when they heard the original end credits.

With two players working independently the majority of the game was very easy. Fighting or befriending enemies was much easier this time around as was compared to the solo battles in the original game. When the set pieces did not load, or when only Player 1 (Mickey Mouse) could trigger an event then it made the game far more difficult. The majority of the game moved quickly for two players, if they were not performing any side missions. The gameplay was smooth and intuitive, as good as most action platformers. The majority of battles were well balanced if not easy as well. Very often however the gameplay would change suddenly into a slow, grating experience. The battles would become extremely difficult and feel very redundant. It would feel like an insult to the players when their progress was suddenly halted. For example Gus the Gremlin would drop the same hint over and over if a puzzle wasn't solved within a set amount of time. He would not offer alternative strategies.

In the past two weeks Alice and I have found ourselves more frustrated than pleased with the game. We enjoyed the world that Junction Point created, the details that they filled the game with, the pins, costumes, wonderful personalities and experiences. However there is a difference between looking at the game and playing it. Pulling the experience out of EM2 was a chore. The story felt lacking and disconnected. The fear of Oswald being forgotten again was not fleshed out, why Prescott the Gremlin felt unappreciated and how the Mad Doctor set him up and then brainwashed him was a bit deus ex machina. Despite everything added to the game, including the voices, we did not feel as connected to the story as we did with the original game. Other comparative "epic" experiences like God of War, Shadow of the Colossus and Zelda did not feel broken. The player felt rewarded for exploring those games. They did not have set pieces that failed to load or a hint system that kept interrupting the player or insulting their intelligence. Gamers did not feel like they were being punished for missing an item or making a bad decision.