Yesterday I asked if Epic Mickey was the new Castle of Illusion or the new Magical Mirror? It Epic Mickey was to be compared to any game before it, then it would most accurately be described as the new Mickey Mania. It was a love letter to the character, the films and the legacy that made the mouse an international star. The early news described the main villain as one that had appeared once before in 1933. What most gaming sites and magazines failed to mention was that the Mad Doctor, level and all, had appeared in 1994's Mickey Mania as well. Right from the get-go it seemed as if gamers and the press had already begun forming their own opinions on the game before it was even finalized. Epic Mickey would be compartmentalized by the gaming press and handed down reviews based on concept art and ideology rather than content and design. This blog will try to unravel the details, mechanics and design that went into the game and explore the reasons why it was received with criticism by many media outlets.

As with most reviews we should talk about the story of Epic Mickey. This game was a character driven experience. It was not solely about Mickey, but by every character that he came across through the course of the opening cinema and the levels themselves. In order to make the story connect with gamers the character of Mickey Mouse had to be presented as a complex and flawed character. All of the cues that Warren Spector and the people at Junction Point used were from the Mickey films themselves. The earliest movies featured a character that was equal parts fun and feisty, not always friendly. His curiosity would get him into all sorts of adventures, some dangerous but most lighthearted.

Junction Point made sure to animate a version of the mouse that looked far more retro-inspired, more two-dimensional like a comic-strip character, than the 3D models featured in Kingdom Hearts or the DSN sport games. Junction Point even managed to keep Mickey’s ears in a constant 2D perspective like in the comic books, even when he turned his head. This helped take the mouse back to the elements that made him a hit. This look allowed Spector to show rather than tell audiences why early Mickey was an important character to animation and pop culture. He could be cheeky and selfish when he wanted to and did not always rely on his friends to round out his personality. In the early films Mickey conveyed many of the same qualities that Donald, Goofy and Pluto got credit for. He had a temper, a silly side and a sincere loyalty. The mannerisms, curiosity and fight of Epic Mickey were in stark contrast to the way the mouse was presented in Kingdom Hearts.

Square-Enix presented Mickey in the format that most audiences are familiar with. Perpetually a hero and always noble of heart, Mickey Mouse was everyone's friend. The difference was that KH gave him a fancy wardrobe with lots of zippers.

Unfortunately the version of "King Mickey" was also bland and uninspired. A character that was more saint than hero. Like many Disney characters that appeared in KH Mickey was added to help push a convoluted plot along. A hero that was perfect could not tell a story, there would be no dramatic expression they could convey, or genuine sense of loss or even joy. From a design standpoint a perfect Mickey could only exist as a deus ex machina, appearing at the end of an adventure to pull a character out of danger and then disappearing. The best characters, heroes and villains alike have traditionally had a flaw. Perhaps gamers never wondered why the main character in Kingdom Hearts, Sora, came from a broken home. It made for a more sympathetic character and one which was more complex than what gamers gives credit to.

The mouse in Epic Mickey was anything but perfect. He was far more relatable to audiences because he didn't have all the answers to the story. He got caught up in a mistake he had made and forced gamers to help write the path out of his dilemma. The premise was simple; Mickey Mouse had gotten into the sorcerer Yensid's workshop and ended up spilling magic paint and thinner on a model city, a place for forgotten cartoon characters. The paint ended up creating an animated ink blot that Mickey tried to erase away. This mistake would grow and grow, eventually becoming the Phantom Blot, a villain that harassed Mickey in the old comic adventures. Mickey ran away from the scene when he heard Yensid returning. Yensid served as the narrator of the game. He was also featured in the film Fantasia for what was considered to be Mickey Mouse’s greatest role as the Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

As the story goes years later Mickey Mouse grew in fame and popularity and completely forgot what he had done to the model city and the citizen therein. The Phantom Blot appeared from behind a magic mirror to pull Mickey into the "Wasteland" and trap him there. Gamers were dropped into the middle of the action. Mickey was strapped to an operating table by the Mad Doctor with a giant machine trying to pull the heart from him. Gamers immediately had to find out where they were and try to find a way out. The first thing was to get away from the giant machine by navigating a dark and twisted castle. Junction Point introduced a character to guide players, act as a traveling companion to Mickey and also serve as a moral compass. By extension he was also a moral compass to the game players, suggesting course of action that would be constructive or destructive.

Gus the Gremlin, from the lost Gremlin project would be the first of many lost characters that were brought back from the Disney archives specifically for the game. Gus served to teach players how to use paint and thinner from a magic paint brush and other game mechanics. The other characters introduced, like Horace Horsecollar and Clarabelle Cow, helped pull the gamers through the world and introduce layers of detail pulled from decades of Disney lore. These supporting characters created branching missions that ran parallel with the main plot of returning Mickey home. Each of these side quests could be explored or ignored, the choices of which would influence the ending movies in the game.

The in-game characters were all modeled in 3D, retro-inspired and cartoonish. Most were in black and white and maintained a familiar squash and stretch format of early animation. They harkened back to the time when Disney was growing by leaps and bounds and new characters were being introduced to the universe on a weekly basis. Sadly Mickey did not recognize most of his early colleagues when he met them. The lynchpin of these forgotten characters, the one that came before all of the others, and even before Mickey himself was Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. Oswald was very jealous of Mickey’s success which he believes should have been his own. The true heart of the game would revolve around Mickey trying to make amends with Oswald. To atone for the thinner accident and try to undo the damage he had caused.

The cinema versions of these characters appeared as if they were illustrations from a children's book brought to life. They were animated superbly by Powerhouse Animation Studios Inc. the style of which helped bridge the Disney Comic and Animation traditions with those of its newer videogame one. The mechanics of using paint and thinner served as the focus of the gameplay elements. The paths and ending of the game changed depending on how gamers used paint or thinner to solve puzzles and defeat opponents. The more paint thinner gamers used to solve problems the more Mickey would drip floating ink and have his face blur, similar to the Phantom blot. Using a paintbrush kept Mickey in a mostly solid state. Thinner could be used to knock down the environment, make walls disappear and dissolve opponents. The mechanic of fixing or destroying the environment was first made popular in Super Mario Sunshine. The paint and thinner mechanic worked very much in the same way that Mario's water canon cleaned up Isle Delfino.

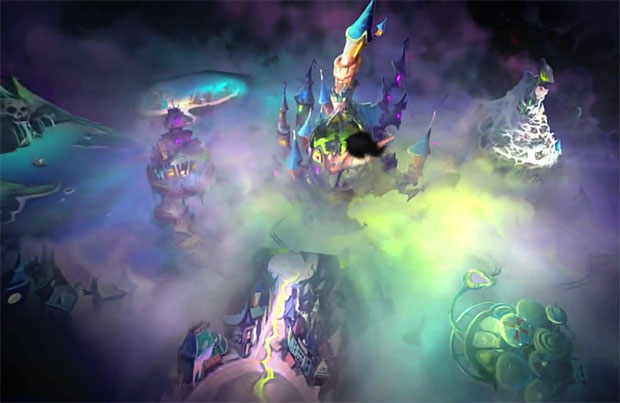

The levels and themes that made up the wasteland took full advantage of the play mechanics. It was the amount of detail that Junction Point put into the game that set it leagues apart from every other Disney game to-date. The world that Epic Mickey takes place in is the model for forgotten characters. We are constantly reminded that the world is an illusion by seeing false walls, painted alleyways and closed-off sections. Gamer might think that the model was based on the original Disneyland. They would only be partially right.

Each major level was broken into two basic components, a staging area, which introduced gamers to the theme of the level and the adventure stage itself which could be compared to one, or a combination of several, major rides in the actual parks. For example Bog Easy was the New Orleans type theme area with Lonesome Manor being the main attraction. In Disneyland that would be akin to Orleans Square being the home for the Haunted Mansion. Junction Point took many cues from the theme areas of the parks, including the rides, and amalgamated them into the stages. The tiki look, complimentary colors lush greenery and tropical atmosphere from Ventureland was inspired heavily from the Enchanted Tiki Room.

The kaleidoscope of color and patterns that made up Gremlin Village was undoubtedly based on “it’s a small world” featured in Fantasyland.

While Walt Disney gets credit for the parks, it was anything but a one man project. His best artists and designers, creators like Roland “Rolly” Crump and Mary Blair, moved from the animation studio to Disney’s World’s Fair projects (precursor to a lot of Disneyland tech) and became some of the most influential “Imagineers.” Their fingerprints are all over the parks, and by extension, all over Epic Mickey.

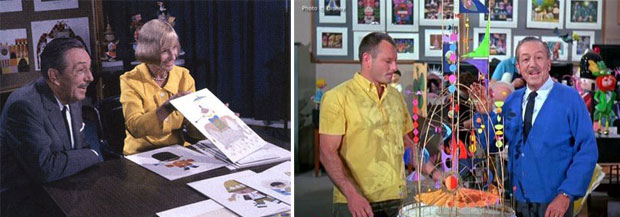

It was many of Crump’s designs which lent themselves perfectly to the look of Ventureland. Mary Blair was a genius of color and design, whe created the inspiration for it’s a small world. The design of Tortuga, Skull Island and the Jolly Roger preserved many of the elements from her original art for Peter Pan as well.

These cues were taken in a different direction by Junction Point and distorted into twisted relics of the designs and parks that Walt had envisioned. The thinner accident stripped away the wholesome elements of the parks and left gamers with a barren version of the areas.

The amount of work and detail that went into the levels was redoubled for the interior shots of several buildings. Junction Point exploited a lesson from classic cartooning here. There were no straight lines, no fixed angles in a cartoon world. Cabinets were rounded, edges kept soft and perspective a matter of layout rather than 3D modeling. The end result was yet another layer of detail that the studios could be proud of and gamers could explore again and again.

Each of these parks were connected via movie projectors. This gaming element was written in as a way for Mickey to cross the oceans of thinner separating the parks. He could jump into a classic cartoon playing on a projector screen and navigate to the next area. The cartoon levels were presented in a side-view-format, very much like all the early 2D Disney games. The stages preserved the music, characters and even visual style of the individual films. Players could collect movie reels and unlock bonus material in each of these levels.

Older gamers were reminded of the good times they had with Castle of Illusion or Mickey Mania. New gamers got a taste of how the good early Mouse games played in each of these film levels. Characters from the classic films turned up in many of the levels of those early titles and they were faithfully reproduced in 3D for modern audiences as well.

Navigating the Wasteland was not without its own perils. Using the paintbrush or thinner Mickey could either befriend or fight the inky monsters that answered to the Phantom Blot. Mickey could use a spin attack to knock back opponents or trigger level action with a shake of the Wiimote. He could also be assisted by pixie-like sparks that acted as paint or thinner guardians of the world. Junction Point's original minions called "Blotlings" were ink-based monsters, rough and unshapely. They helped balance out the polished cartoon citizens of the wasteland. These monsters also reinforced the story that Mickey's mistake caused not only the world to become misshapen but also the creatures that inhabited it.

The criticism behind the game was twofold, one was tangible, gamers and critics alike found fault with the camera, the other major complaint was more subjective, that Epic Mickey somehow did not live up to the concept. We shall explore these things tomorrow in the final part of this review.

As always if you enjoyed this blog, and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment