A blog about my interests, mainly the history of fighting games. I also talk about animation, comic books, car culture, and art. Co-host of the Pink Monorail Podcast. Contributor to MiceChat, and Jim Hill Media. Former blogger on the old 1UP community site, and Capcom-Unity as well.

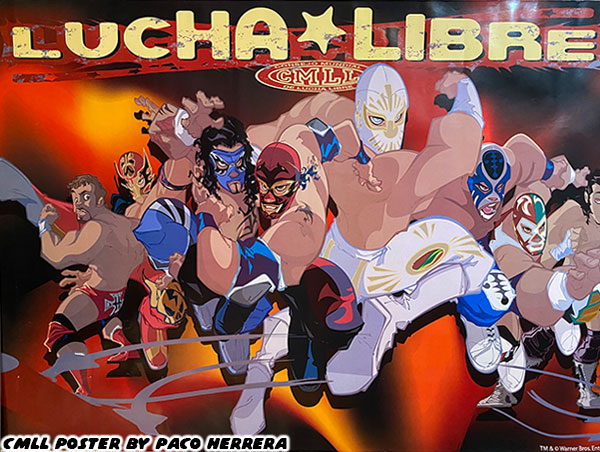

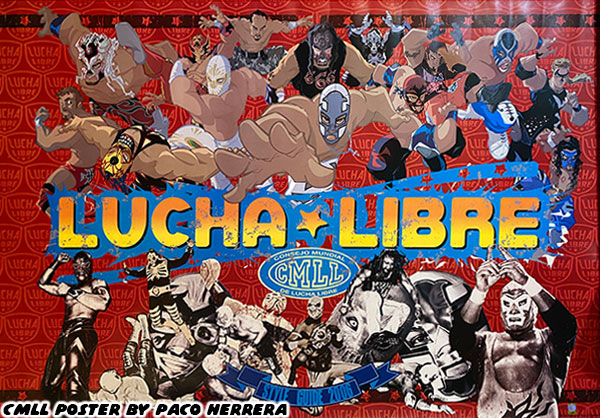

Sadly some of the wrestlers are retired or no longer with us. It's one of the reasons I love the posters that I collected. They are a snapshot of an era.

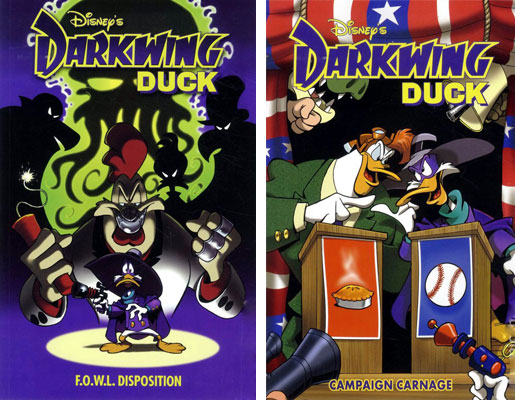

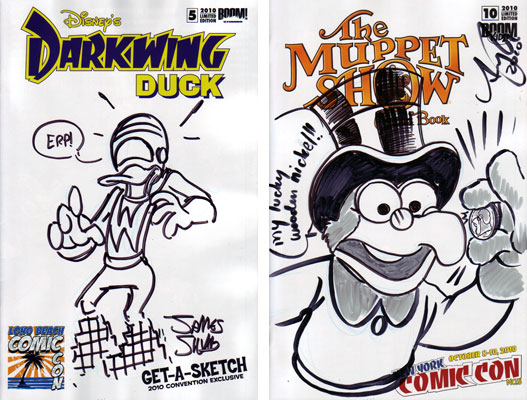

Howdy friends, this blog goes out to the comic book readers and fans of the old Disney Afternoon series. As many of you may have heard the license for Disney comics has expired and Boom Studios in the US hasn’t been handed it again. No word yet on whether or not Marvel will take over. In the meantime the talented James Silvani and Amy Mebberson are in creator limbo, not forgetting the uncredited writing talents of Aaron Sparrow. The best thing fans of the classic Darkwing Duck series could do is pick up the issues or trade paperbacks of the book and show Marvel that Disney comics can be a hit when put in the right hands.

The most recent books F.O.W.L. Disposition and Campaign Carnage keep the sharp writing and amazing art fans of the series have grown to love. Readers owe it to themselves to add these books to their collections. Fans have a chance to show James, Amy, Aaron and series creator Tad Stones that readers support their work and would like to see them keep going.

Readers of the series would also get a chance to read a story possibly influenced by me. I say possibly because there’s no way I could prove it was more than coincidence when a rare Darkwing character from the TV series returned in the Toy With Me story arch featured in the Campaign TPB. I wrote a blog about my experience at last years’ Long Beach Comic Con.

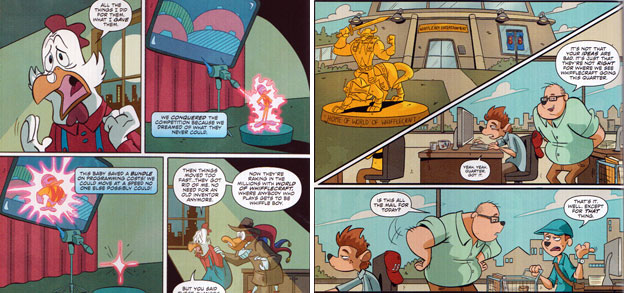

I had asked James to sketch Wiffle Boy for me and the rare character stumped both he and Tad. They had to look up the episode for the character reference. Well a few months later the character appeared in a Darkwing Duck Annual. Not only that but the game company had grown from the 8-bit inspiration from which Wiffle Boy was based to reflect the more modern world. This time he is a mascot for World of Wifflecraft.

I'm certain that longtime 1UP member, and current Blizzard Production Diva, Erin Ali might find some humor in that. Anyhow I hope that you get a chance to read the books, they really are among the best stories out now. Let me know if you've gotten a chance to read through them.

As always if you would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

Warren Spector was passionate and knowledgable about the Disney universe, this message was obvious in Epic Mickey and his DuckTales story thus far. As a die-hard Disney fan he was familiar with the work on most of the television shows and especially the comic books. He knew the various incarnations of characters in comics produced domestically as well as overseas. Through Kaboom Studios Mr. Spector was able to find a good middle ground between the comic canon laid out by Carl Barks, the animated canon of DuckTales and the Eurpean take on the universe as well.

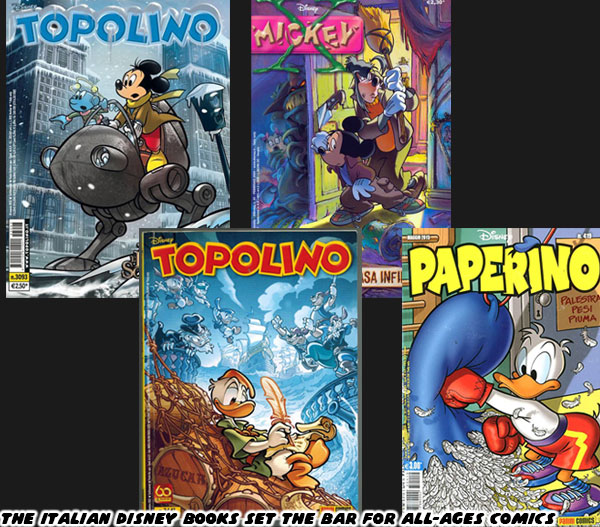

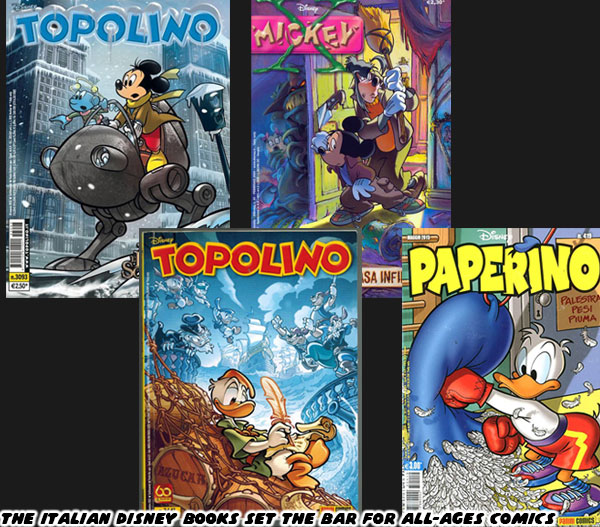

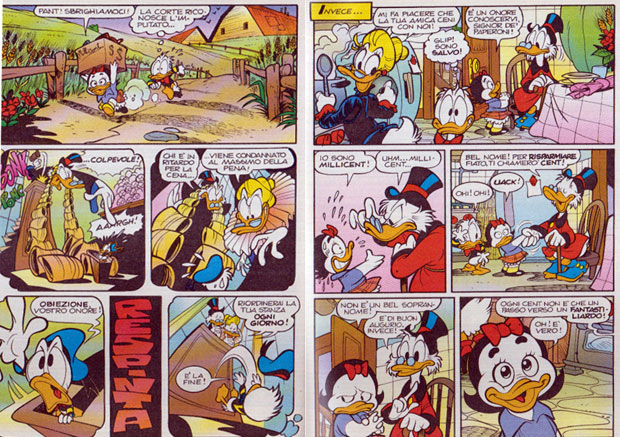

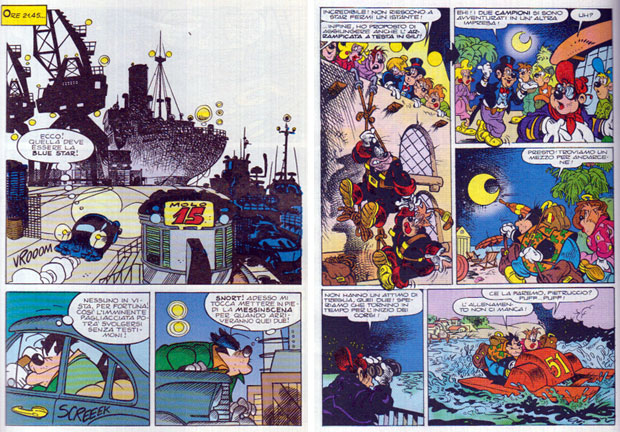

The first issue of Warren's DuckTales had a strong visual impact. This was because of the differences in coloring between American and Italian comics. In Italy the artists that worked on Topolino magazine were also the inkers and colorists. The magazine itself was full color but the turnaround time was very short. Each issue of Topolino averaged 180 pages which meant that artists had to have pages pencilled and inked at a rapid pace, leaving little time for artistic touches.

In the US most comic books averaged 24-36 pages and the inking and coloring duties were often delegated to specialists. This meant that the art on many US comics had a stronger visual impact than those featured in Topolino. The colors used in the various Topolino stories were solid and flat, there were almost no shadows, midtones or highlights on any character. The colors themselves were very bright but rarely did they have any gradation. The massive volume of pages turned out could explain why the art was minimalistic.

Some of the better artists in Topolino used rendering techniques in ink to create gradations for the panels while still using flat colors underneath. Unfortunately these artists and stylistic panels were few and far between. The best coloring jobs usually ended up on the covers or on promotional material.

Kaboom Studios went with western coloring team Magic Eye Studios for the pages of DuckTales. This same team helped color several of the other Disney comics published by Kaboom including Darkwing Duck. Many of the panels in Darkwing Duck for example took advantage of digital coloring effects. Characters could be colored, given highlights, shadows and mid-tones and then on top of that have lighting, transparencies and even blurs and weather effects added to the art. These were coloring effects that would have been impossible with the traditional techniques used in Topolino. Advances in digital coloring, effects, higher quality paper and digital presses allowed the art featured on the pages of Darkwing Duck and DuckTales to match the vivid style of the animated shows they were based on. At the same time these techniques were also more time consuming than those used overseas.

These advances weren’t cheap either, the cost on average for a comic book had shot up to $3. The trade off of quantity versus quality pages of art and story was worth it for US consumers. They had grown to expect a high level of visual impact in the graphics department, especially since digital coloring and magazine-quality paper had been a standard for over a decade.

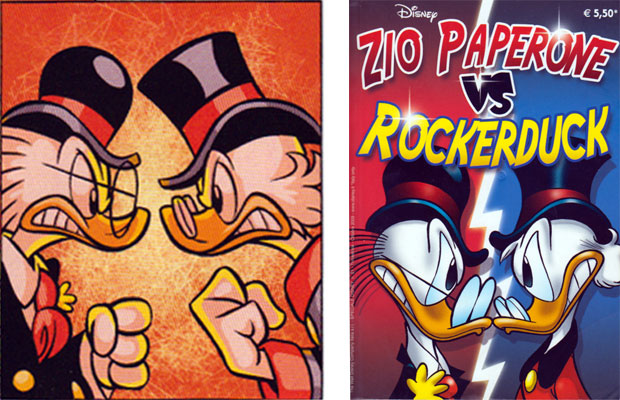

The Spector version of the DuckTales universe became much more interesting because of the choice for rival. Mr. Spector’s comic worked in regards to the Italian approach of villain choices Rockerduck was the tycoon with little respect for Scrooge’s hard-earned fortune. The fact that he was a younger and more impulsive mogul gave him a bigger chance for doing something brash to Scrooge.

Warren slipped Rockerduck right into the start of story and kept pushing forward with the plot masterfully. He knew that readers unfamiliar with the character would pick up instantly if he was supported with great dialogue and shown doing something devious or underhanded later on.

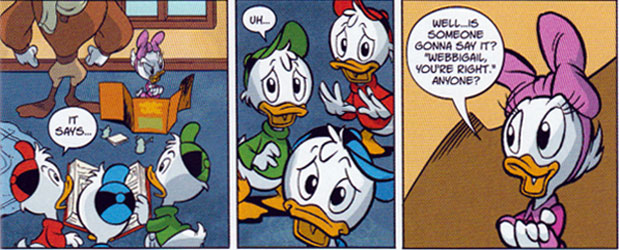

At the same time Warren did not completely ignore the established US canon for DuckTales. That was why he went with Webby as the character that could get the ball rolling on a new adventure. Her innocent voice would have sold the idea of returning treasure to the rightful owners. This plot could then easily unfold into a more grand adventure.

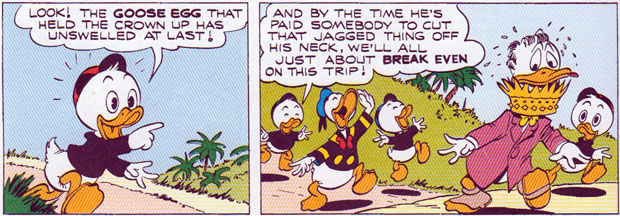

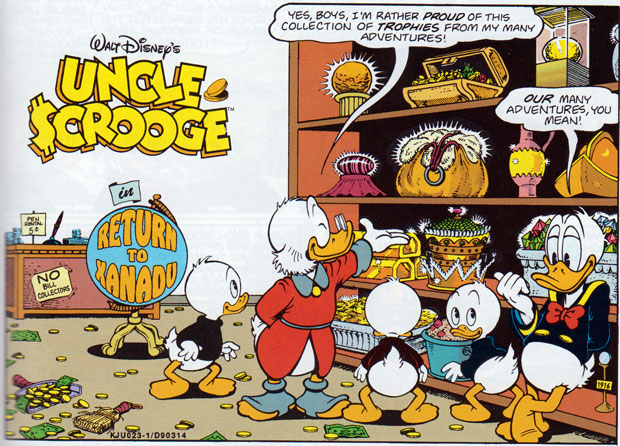

The story by issue #2, included a return to the island of Ripan Taro and a cameo from a giant jellyfish featured the classic Carl Barks story of The Status Seekers. Mr. Spector had filled the adventure with many nods to the classic comic adventures. The entire series thus far seemed to be rooted in a lot of nostalgia and material that had been covered in previous adventures. In the museum on the first issue of DuckTales the characters pass many treasures that had been gathered over the decades of the classic Barks stories. Scrooge even mentioned how some treasures were added to his collection from the adventures of other characters. Like how the crown that got stuck around Gladstone Gander’s neck in the Secret of Hondorica was now featured in the museum.

These nods to the canon established by Barks were great for fans of the comics but possibly lost to those that were only familiar with the cartoon series. Worse, the series thus far seemed to be a retread, if not several layers of retread material.

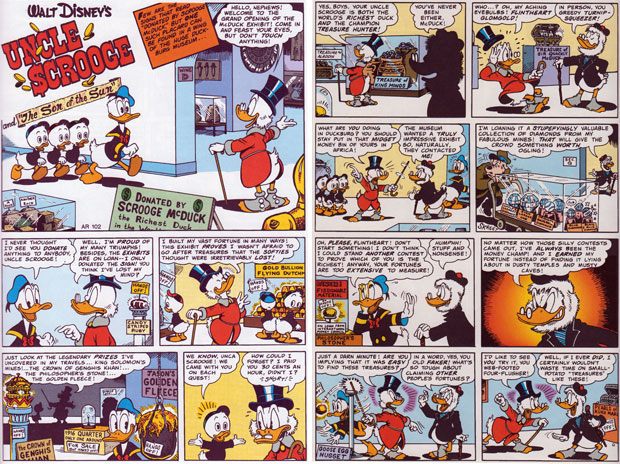

Don Rosa tied up my entire Italian Legacy theme. He was an Italian-Irish-Scottish-American whose full name was Keno Don Hugo Rosa and was named after his Italian grandfather Gioachino Don Rosa. Mr. Rosa was without a doubt the undisputed master of modern duck storytelling. He picked up all of the qualities that made the Carl Barks adventures memorable and then expanded upon them. He was able to connect the dots between actual historical events and phases through Scrooge's lifetime, all while managing to fold those adventures right into Barks continuity. Not unlike the research required to pull off historical Forrest Gump or Dan Brown sleight-of-hand. The problem for the Spector DuckTales comic was how similar it was to material created by Don Rosa. The whole idea of Scrooge having a museum display his treasures had been covered in the the story the Son of the Sun. Those first pages also managed to cram a lot of treasures from canon into the background. In that story Flintheart Glomgold, not Rockerduck, played the major villain.

Flintheart challenged Scrooge to a treasure hunt instead of tricking him into returning the treasures. The winner of the bet would be the one who found the single greatest piece of Incan treasure. This allowed Rosa to revisit the Andes and craft a story that was in the classic vein but completely new to audiences. The story took place geographically in the same part of the world of an earlier story yet there was no overlap of specific locations or even supporting characters. The same could not be said of Spector's DuckTales story. It was the Status Seekers in reverse as it took the Candy Striped Ruby past a giant jellyfish to the island of Ripan Taro to be returned to King Fulla Cola. To be fair Don Rosa also revisited Barks locations and canon and in one story had even written the adventure path backward from the original story as well.

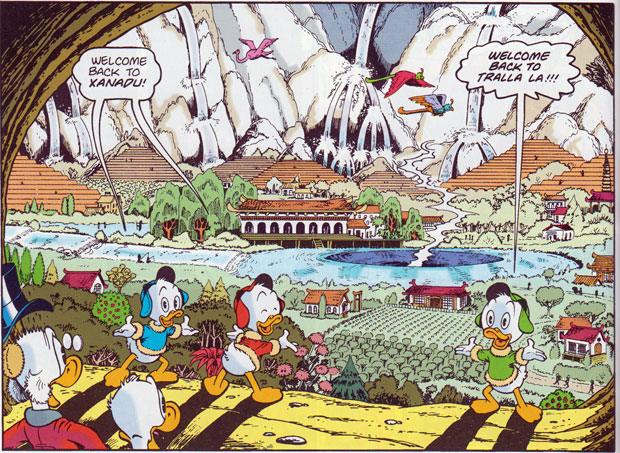

In the story Return to Xanadu Scrooge, Donald and the nephews went on a new treasure hunt. The ducks used historical data and even the poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge to track down a location for the final resting place of Kubla Khan. Scrooge knew the legends of the fabled location must have been true because he had the crown of Kubla's grandfather Genghis Khan. He had retrieved it from a Yeti hidden in the nearby Himalayan mountains. Most avid fans of the Barks universe knew that the ducks had never been to Xanadu in any prior story yet were eager to find out what Don Rosa was crafting.

Rosa took the ducks across some very interesting and exotic locals and the entire journey supported the clues and historical data through winding mountain passes and hidden underground tunnels skirted by a river which went on for miles. Eventually the ducks came across an enormous underground reservoir and a bridge that had been destroyed leading up another tunnel. The poem suggested they were indeed following the right path because in order to reach Xanadu they had to go backwards through the locations described.

"It flung up momently the sacred river.

Five miles meandering with a mazy motion

Through wood and dale the sacred river ran,

Then reached the caverns measureless to man,

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean"

The ducks found a way across the river by damming the lifeless ocean and walking up another tunnel. What they discovered was breathtaking for both new and old fans. The hidden valley of Xanadu turned out to be the same one visited decades earlier called Tralla La in the Carl Barks Story Time To Dream. This serene place was in and of itself was a take on the hidden valley of Shangri-La. Don Rosa sublimely gave that valley a back door under the guise of a completely new treasure hunt. Where the story went from there was pure genius. I would be hard pressed to find a fan of the universe that saw this revisit of a classic location coming.

The DuckTales adventures by Mr Spector did not seem to have the same hidden path or "back door" to a greater adventure. In the two issues presented thus far everything was plainly laid out and foreshadowed with scenes featuring a saboteur. The art was fantastic, the nods to comic book and cartoon canon were great but the story did not seem to have enough substance. There was too much reliance on fanservice and nostalgia and not enough story construction. By comparison the pilot series of the DuckTales cartoon, the search for the Treasure of the Golden Suns was a fantastic and completely original adventure. Written by Jymn Magon, Bruce Talkington and Mark Zaslove the series captured the spirit of the Barks and even Rosa adventures without overlapping into any previous stories.

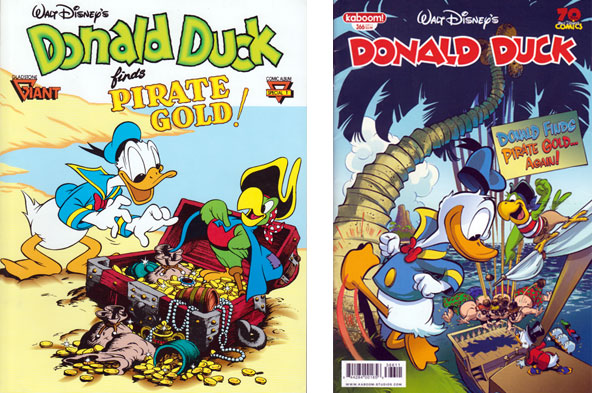

The lack of substance and reliance on established canon for the new DuckTales comics was indicative of some traps that other Disney comics were falling into. The stories were becoming too safe, too childlike rather than family oriented. Even the very first Carl Barks comic Donald Duck finds Pirate Gold! had recently been revisited by Kaboom studios in the story Donald Duck finds Pirate Gold… Again!

The DuckTales comics had just started and I was undoubtedly being too heavy handed with my criticism in this blog. However in order to make the series work with new and returning fans Mr. Spector has to take the rest of the series into some figurative and literal unexplored waters. For those stories I cannot wait. If you were a fan of the television series and want to rekindle those memories then you owe it to yourself to pick up this new series. They would be big hits for Disney fans, especially those that play games and read comics as a family. I hope you enjoyed this series. If you have any comments of questions please let me know.

As always if you would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!