In keeping with the recent Disney themes this next series is going to take a look at the ways in which Europe approaches and develops the classic characters in popular media. To narrow down the scope of the series it would be focusing mostly on how Italy handled the Disney universe through Topolino magazine. Topolino was the name of Mickey Mouse in Italy. I had talked about the toys that came with the books in a previous blog. How Italy handles the Disney name and how they have been pushing to keep it relevant for several generations could teach many things to the parent company in the US.

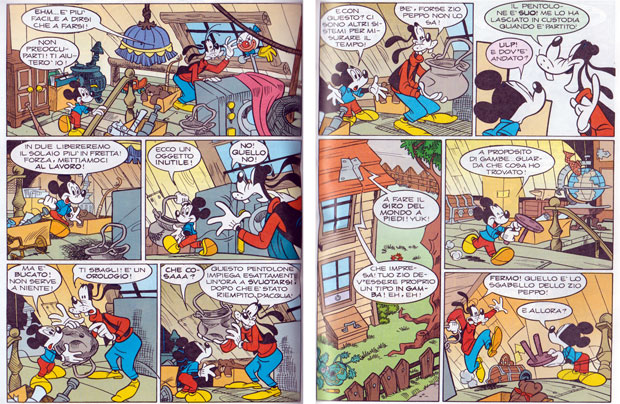

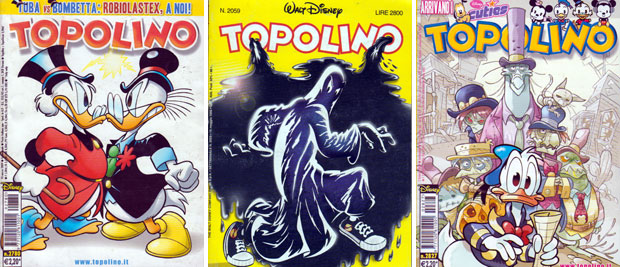

The Italian word for comic book was fumetti, it literally translated to puff of smoke. This was in regards to how the word bubbles in comic books looked like clouds. Topolino was one of the rare western comics to be published in Italy’s pre WWII era. It had been in publication since 1932. Like most other Disney comic licenses the earliest issues were reprints and collections from the west. As demand for everything Mickey Mouse rose so too did the demand for more comics. Within a short amount of time local artists were emulating the Disney style and developing home grown stories to fill in the issues of Topolino.

The artists and writers working on Topolino managed to incorporate the characters from the various Disney animated shorts just as well as characters that appeared in western comics originally. Through the issues they helped entertain and educate audiences on the library of Disney characters and how they interacted and related with each other. The same thing could not be said of many western Disney fans, especially those that were familiar with the cartoons and parks only.

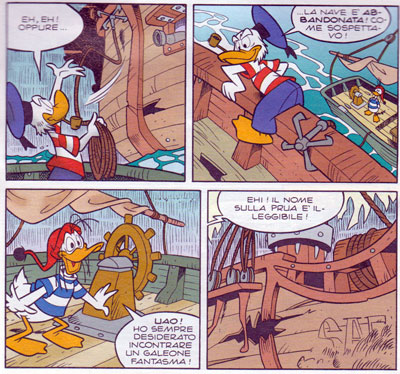

Unless Disney fans in the USA were exposed to the classic comics and rare cartoon appearance then they might not know that the adventurous Moby Duck and the hapless Fethry Duck were part of canon. Or that Fethry was related to Donald Duck even! Their adventures and appearances did not end abruptly in fumetti as they did in the US in the 1970’s. To audiences in Italy the two ducks were every bit as involved in the universe as any of the more famous Disney mascots.

Topolino helped keep these minor characters relevant and developed their identity and appeal among readers. They did so by incorporating them in stories with the more recognizable characters but also by letting them to grow in their own adventures. The types of stories and adventures that the characters were featured in fumetti were becoming as memorable as those featured in the USA comics.

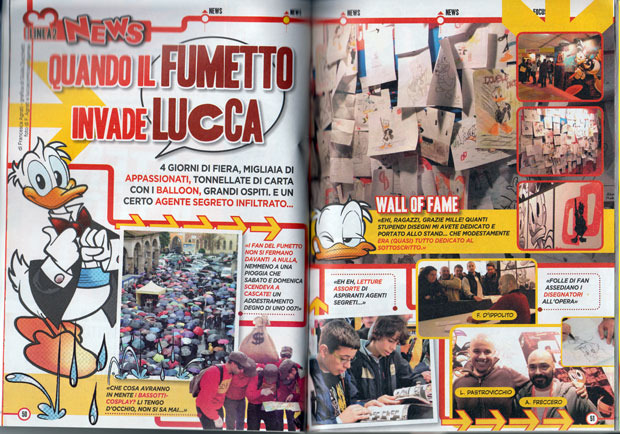

After more than half a century in publication the audience for Topolino had grown exponentially. It was diverse and not solely limited to children. Many Topolino fans were third and fourth generation readers and collectors. The publishers managed to appeal to every age by offering different things to their audience, from short gag comics to longer serials. Although labeled a fumetti Topolino was not considered a comic book as much as a magazine because of how much content was packed into the publication.

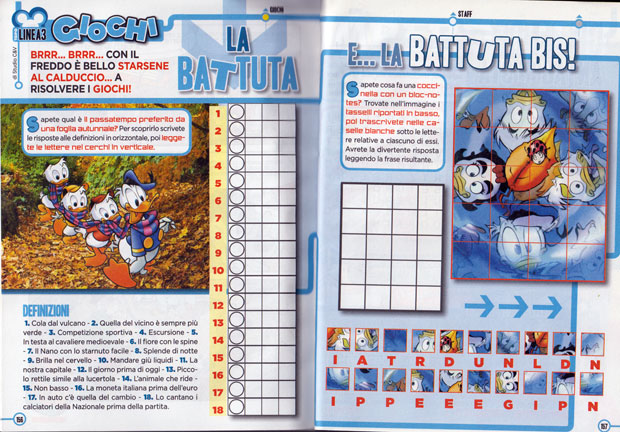

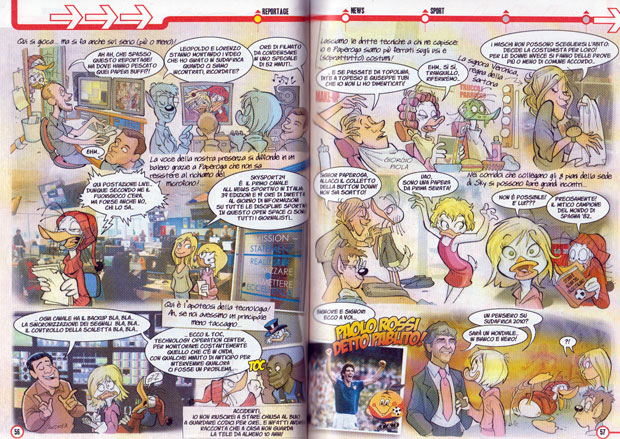

Each issue of Topolino was not only filled with comic stories but also interviews and articles on movies, music and events. There were news stories and interviews with popular celebrities. The issues also featured previews and reviews of toys, videogames and electronic gadgets. Puzzles and games were included to entertain younger readers.

The extra content did not end with some puzzles. To help educate younger readers there was often a look at popular careers. For example a few characters from the comic would visit an actual television station and try to find out how the news was put together. Artists would incorporate photographs and create caricatures of real world people to interact with the cartoon icons. They would help explain their careers to audiences. These brief entries in the book gave many artists a chance to showcase their talents in ways that traditional comic formats did not always allow.

The biggest lesson that the fumetti could teach US comic publishers was in how the creators were granted artistic license. They could explore the Disney universe and present it in a diversity of formats. This liberty to explore and expand on the canon was rarely seen in the USA. Part of the reason was because in the USA comic books, and especially Disney comics, were meant to appeal to children. US comics had to be geared, developed and marketed to children. This limited the scope of stories and characters that could be created. Fumetti were open to all-ages and could be enjoyed by just about any reader. Similarly in Japan there were manga titles written for adults just as there are for teens and children. Countries like Italy, Brazil and Japan did not have a stigma attached to the medium. They also did not use the business model attached to the Disney comics that the US did.

Characters that had only made a few appearances in US comics had taken starring roles in fumetti. Entirely new characters and canon were explored without Disney fans and purists calling for a boycott to the changes.

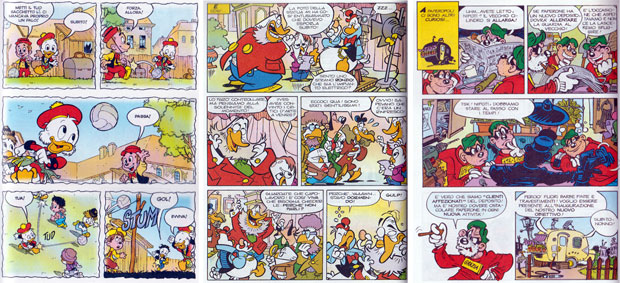

For example if a writer for Topolino wanted to feature a young Scrooge McDuck in a flashback story about calcio (Italian for soccer) then they could do just that. He would be running around in a kilt playing against kids in shorts in a neighborhood yard. In the US it would be hard for fans of the Carl Barks canon to accept the visual changes to the character, or to see him cavorting with neighborhood children instead of being dressed shabbily and working towards his first dime.

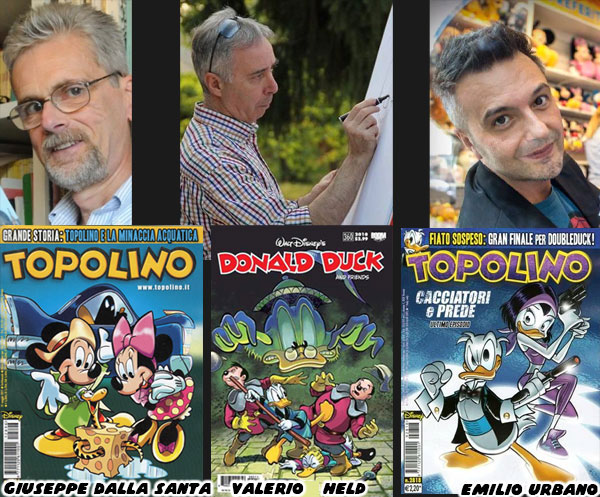

Each artist working in fumetti was free to explore a style of presentation and cartooning. Some artists had a distinct 2-dimensional style while others featured more convincing 3D forms and shapes. Some were great at the classic style of character art, making figures that looked exactly like those featured in USA comics from the 40’s and 50’s. Others had a more impressionistic stance, with flat and stylized versions if the icons that were definitely not based on the US model sheets.

If Italy were to be ranked globally in the art of comic cartooning based on Topolino and its fumetti offshoots then they would arguably at the top with the US well behind them. The sole publisher of the Disney comic book license in the USA was Kaboom studios, the offshoot of Boom Studios. They had assumed sole ownership of the license from Gladstone and Gemstone publishing. Often times Kaboom and Boom were reprinting older Disney material from the US and Europe and only developing new material from recent Pixar films. The books from Kaboom were marketed mostly to kids but also to the older fans of the Disney Afternoon television series. Some of their best artists like James Silvani and Amy Mebberson were sometimes overlooked by the community simply because of the titles they were working on.

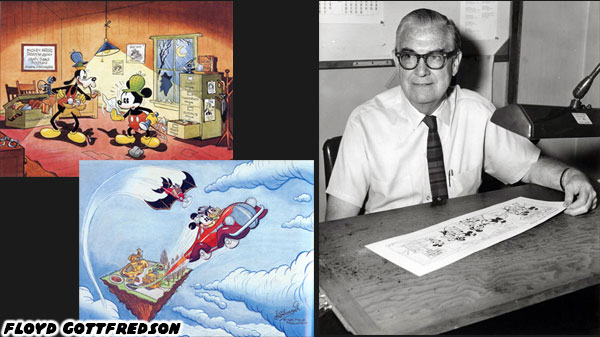

Of all the Italian artists, the one who has had the biggest influence on the Italian cartoon style and the one who was most emulated was Giorgio Cavazzano. He was and is very much considered a living legend among cartoonists, to be admired alongside such greats as Carl Barks and Don Rosa. Giorgio got his start in comics at the age of 14 by inking the pages of the original Italian legend Romano Scarpa. He was still in high demand as a cartoonist, only now his work also hung in museums. Many of the current Topolino artists and product designers still borrowed a lot from Mr. Cavazzano's style.

Subscribers of Topolino were treated to collectables and toys in many of the issues. Smaller collectables like puzzles, cards, stamps and coins would come packaged with the fumetti and larger toys would be distributed over several issues. The larger toys would have to be assembled by the readers, which for most young fans was a treat in and of itself.

Many of the larger toys had some sort of battery activated feature. The space ship pictured above for example had working lights and sound effects. It could be separated into three components, a satellite rover, a ship and a command module.

These items or “gadgets” as they were known in Italy did not have to be part of a story. Many were just be based on any part of Disney history. The printed gadgets featured images from the Disney legacy, others were actual figures and models. Some were even crossover designs from multiple Disney sources such as Tron Mickey on a wind up light cycle or Donald Duck in Herbie the Love Bug.

Disney followers in Italy had probably a greater breadth of knowledge of animated characters, comic book creations and classic films because of how often they were referenced in fumetti and via the gadgets.

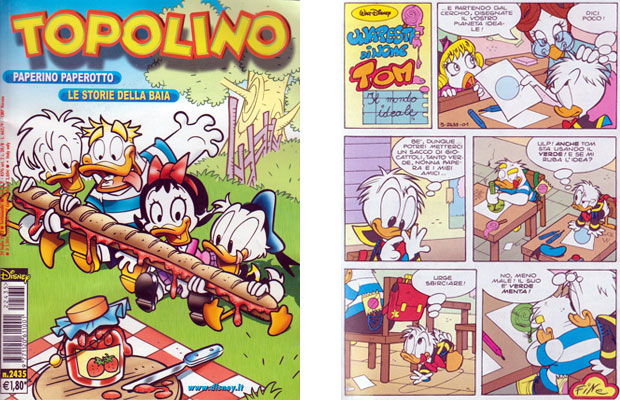

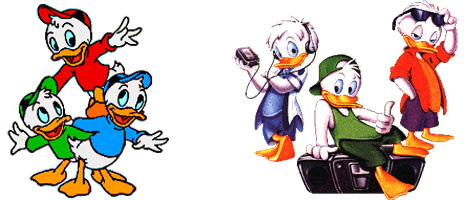

Italy helped introduce diverse timelines into Disney canon as well. Donald Duck may be seen as secondary to Mickey Mouse in the USA but in Italy he is every bit as important if not more so in the fumetti. Paperino, as Donald was known in Italy had several incarnations. One of the versions of the character, Paperino Paperotto followed the adventures of the young duck and his friends. Very little had ever been written or drawn in the USA on Donald’s childhood. Paperotto had a distinct visual style and even purpose in Disney canon. The character and his adventures were far more than a generic "Disney Babies” series. His hi-jinx stories were very sincere and the artists and writers worked hard to respect Disney continuity and as such they were accepted by fans.

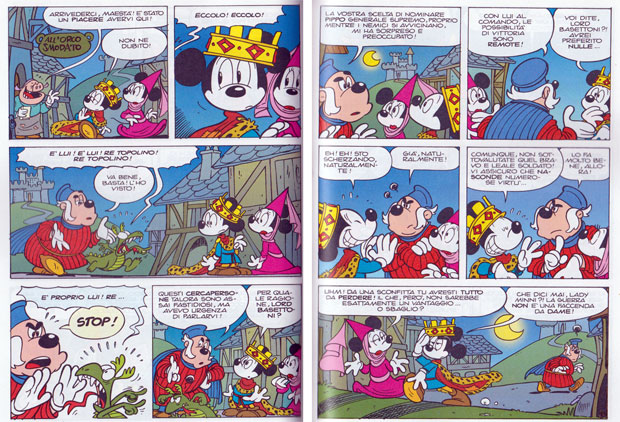

While these whimsical stories were meant for younger audiences they were balanced out by the more adventurous stories of Paperinik, the superhero alter ego of the adult Donald Duck.

Italian fans got tired of seeing Donald treated as a perpetual loser in the translated stories from the US. When the chance arose to create an original story they gave Paperino an alias that was far more heroic and adventurous than even Mickey Mouse. Paperinik was not unlike Batman in that the character relied on his guile and an array of gadgets to defeat a rogues gallery. Paperinik, the Duck Avenger in English-speaking countries and Papernika, the super alter ego of Daisy, had many colorful adventures over the years. The duo and other super-hero retellings of the icons had now been part of Disney comic canon for over 40 years.

Both Paperino Paperotto and Paperinik demonstrated that the Italians were capable of taking classic characters into bold new directions and make them popular with the community. They also showed that the community would not be offended if changes to an iconic character were made, so long as the spirit of the original character were not compromised. Paperotto and Paperinik never crossed the line to make them anything other than Donald in a new form, the personality and temperament of Donald Duck still shown through the artistic facelift. The idea of remaking the Disney icons would be met by a collective groan from US cartoon fans.

Hi Noe, only a precisation: Valeriao Held is actually "Valerio Held". Bye from your devoted italian fan

ReplyDeleteZero, good catch, I'll try to make the edit soon!

Delete