The previous Friday I talked about how Michael Lau set the stage for the urban vinyl movement. Specifically his gallery shows from 1999, and 2001 featuring his 12” figures in Hong Kong, and Japan respectively. While he was exposing the world to a new type of art his friends, and contemporaries were following closely behind, and releasing their own 12” figures to collectors. At best groups like Brothersfree understood the art movement. They weren’t poaching the community that Lau was representing, I’m talking about street culture specifically. Instead the Brothersfree group were trying to carve out their own niche, to tell their own story by turning industrial workers into the heroes of their Brothersworker line. Or Wendy, and Kelvin Mak telling the stories of Hong Kong tradespeople with their 2da6 line. I felt that other artists like Eric So, Jason Siu, and Pal Wong were biting a little too hard on what Lau had established previously.

The Pazo Art figures from Mr. Wong for example went through all the same motions as Mr. So, and Mr. Siu. They were highly detailed, quality sculpts, with realistic fashion. They often came with a change of clothes, accessories, stickers, and all of the trim that one would expect from $200-$300 figures. They also went right after the street fashion look. What got under my skin was that Pal was sculpting faces that were eerily similar to what the gardeners looked like. Michael Lau created a gardener called Future, he was essentially a caricature of established graffiti icon

Futura 2000. When that character was unveiled it was a breath of fresh air. Knowing that he was a part of the gardener community connected their story to the culture. Then seeing Pal going down the same path with his figures felt redundant, and even slightly disrespectful. The smaller figures that he released showed to me that he didn’t understand what the movement was about.

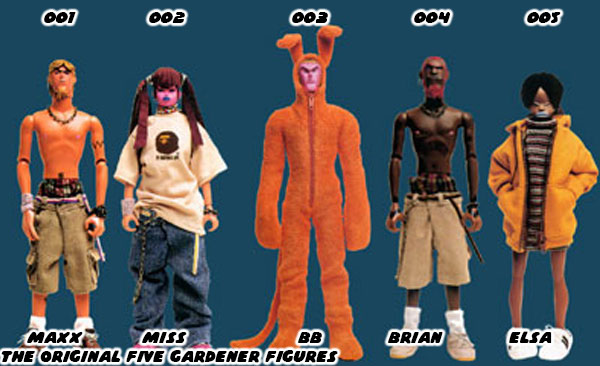

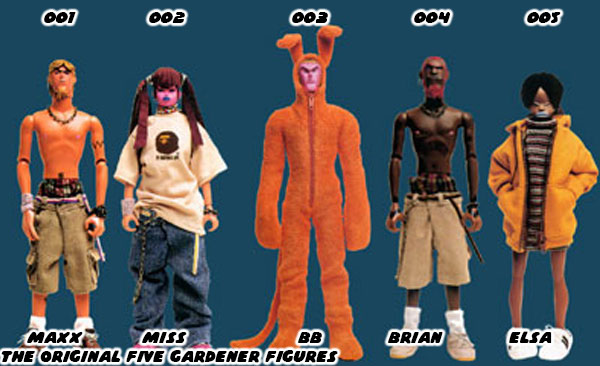

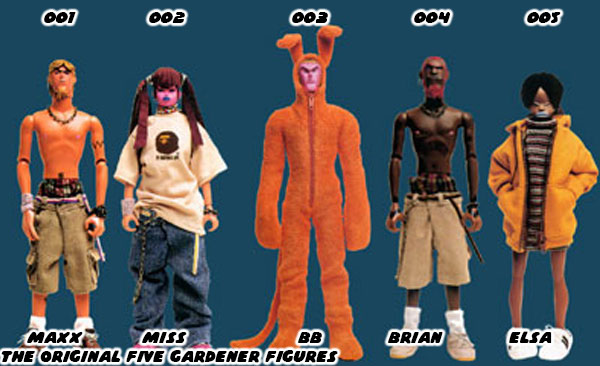

The P.A.S.A. Rapper by Pal Wong was an obvious attempt at capitalizing on the 6” gardener trend. To the casual observer the scale, proportions, details, and accessories were all spot on. He could have been one of the gardeners except for a few things. The sculpt, and paint was an amalgamation of Maxx, and Brian from the earlier gardener line. He was missing a chain for his wallet, and there was no felt wristband, instead it was sculpted, and painted to his wrist. These were all shortcuts to bring a cheaper figure to market, and pass it off to the masses. To make the character slightly different from the gardeners he had an afro, large eyes, and some really thick lips. These things didn’t really capture the spirit of the gardeners, and felt a little bit heavy-handed, if not outright racist. But I don’t want to sweep what Lau did under the rug either. We need to talk about culture, representation, and appropriation with context to this new art form.

Michael Lau had also released a figure with dark skin, and big lips as well. This character was called B/W. He was an African born in Hong Kong. His friends liked him, but he could be long tongued, aka he could be very chatty. He stuck out for several reasons, the most obvious was his jet-black skin, and large pink lips. B/W was the ninth figure of the original 10 gardeners, and was the only one that had skin that dark, and large cartoonish lips. Brian, Elsa, and Uncle were Black characters in the original 10 lineup that looked more like regular people. There would also be a group of basketball characters added to the lineup that had various shades of Black skin, but none as dark as B/W. I would argue that Michael did not intend to use a racist caricature. All of his gardeners had exaggerated cartoonish, facial features. It was bad form to push the envelope that far with B/W. His representation on the rest of the cast was more or less well done.

Why did Pal Wong, and Michael Lau feel that it was okay to present a Black character like this? For Mr. Wong I feel that he was just trying to cash in on the popularity of Lau. He poached his art style, and created a knock-off figure without understanding the culture that Lau was trying to recreate. For Lau I would say it was his lack of awareness he had regarding Blackface. The importance of representation

was something that I had written about previously, especially when it came to fighting games. One of the things that I want to remind you of is that the Civil Rights movement that the US went through in the ‘60s only happened in the USA. Martin Luther King Jr, Malcom X, John Lewis, James Farmer, and the other Black leaders of that era shaped the culture in the US.

There were no civil rights movements similar to what we had in other countries. While schools overseas might talk about it, culturally the UK, Japan, or China did not have anything like what the America went through. There was a good chance that Lau, and his contemporaries did not realize that the big lips character was offensive. This was partly due to cultural relativism, they got the trope directly from the US. That presentation had been a part of US cultural exports to the rest of the world since the late 1800’s. It was seen in advertising, in toy design, and popular music of the era. By the 1940’s Blackface fell out of favor as a form of entertainment in the states. Culturally the new enemy were the Japanese, and Black Americans were signing up to fight in WWII. It was disrespectful for them to return home and see that ugly face waiting for them. So little by little it started getting taken down in marketing. The change got a lot of pushback in many states, not unlike the removal of Confederate statues did as recently as the 2020’s.

The thing was while this trope was fazed out in the USA, it didn't entirely disappear overseas. T

he big lipped characters in pop culture could still be seen through Mr. Popo from Dragon Ball in 1988 (R.I.P. Akira Toriyama), Chocolove McDonnell from Shaman King in 1998, and as recently as 2012 with the release of Anarchy Reigns, the follow-up to Mad World by PlatinumGames. This is why I want to talk about context of the gardeners, including B/W. Lau intended on creating figures based on the street culture that his friends, and he had grown up in. He didn’t go in trying to specifically hurt any ethnic group specifically. Of course that doesn’t prevent people from being insulted.

As for all of the artists from Hong Kong, and Japan that came out right on the heels of his work, they also had to be put in context. Were they releasing figures because they were going for a cash grab? Were they doing this as an homage to Mr. Lau? Could it be both, or neither? Again, it depends on the way we look at it. Designers like Colan Ho, and Joel Chung were releasing pieces very much out of left field. Their figures weren't workers, skaters, breakdancers, or anything else like that. They had their own signature style, but could also work with a license if they had to. It was an interesting time for collectors that wanted unique, high quality pieces. The urban vinyl craze spread like wildfire throughout Asia. Some artists were turning sketchbook creations into 3D representations, some were remixing kaiju monsters with cute, and cuddly toys. This approach was evident in some of the early pioneers like IT Rangers, and Bee Wong.

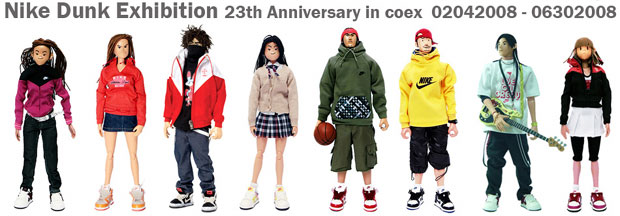

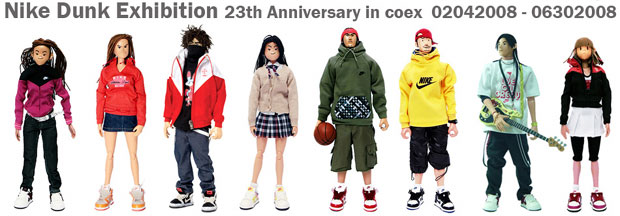

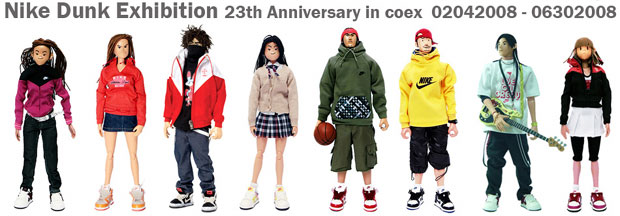

In 2008 South Korean figure artist CoolRain made his debut. He was heavily influenced by Lau, and managed to secure some high profile clients in a relatively short span of time, including Nike,

Adidas,

Vans, and the NBA. Although he designed a number of smaller 6” mini gardener-type figures

for the NBA, he rarely produced a 12” figure that wasn’t

a prop for a commercial, or gallery show. Very few people were able to get their hands on his original 1/6 figures, and these tended to be rappers, and star athletes.

CoolRain was kind enough to do an interview with me. He gave all the credit to Lau for inspiring him. He definitely approached figure art as an art form, and not a way to make a quick buck.

Lau had also collaborated with Nike, and Sony, but he was notoriously hard to pin down by any company. When in doubt it seemed that the corporations could go to CoolRain if they wanted to use the aesthetic, rather than wait on Lau. Was this an example of an artist holding onto his integrity, or being selective about clients? Was CoolRain selling out the culture? It all depends on the context. He understood the line was blurring between art, toy, and collectable. He taught classes, and presented workshops to the new generation of creatives in South Korea. He was very mindful of the communities he was asked to recreate, whether they were skaters, basketball players, or even professional futbol / soccer players. He was just one of many voices helping spread the word about “urban vinyl” and the larger art movement.

The respect I had for CoolRain remained consistent over the past 20 years. It made me reconsider what I thought about other artists appearing in the early 2000’s as more than just poaching the work of Michael Lau. I’ll talk more about it in a future blog. For now I’d like to hear your thoughts. Could art be controversial, or accidentally racist? Would context be important in exploring, or explaining the relationships between ethnicity, stereotype, and culture? Tell me about it in the comments section. As always if you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment