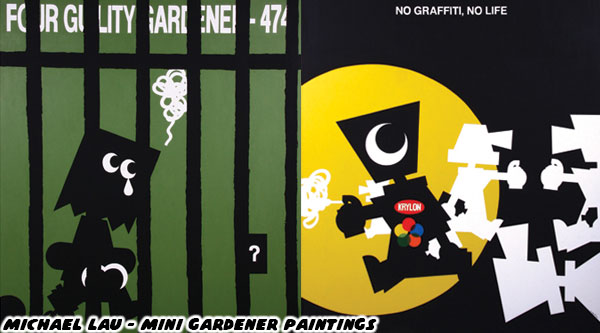

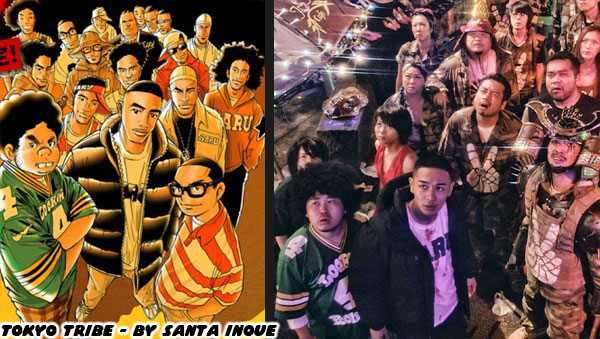

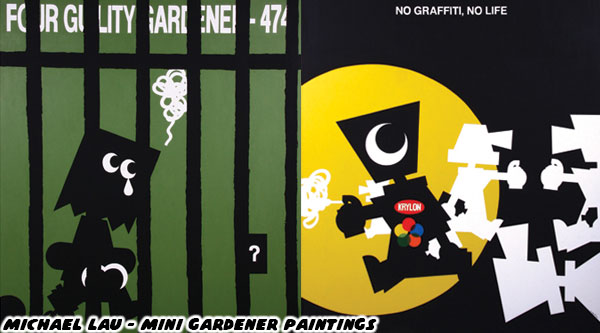

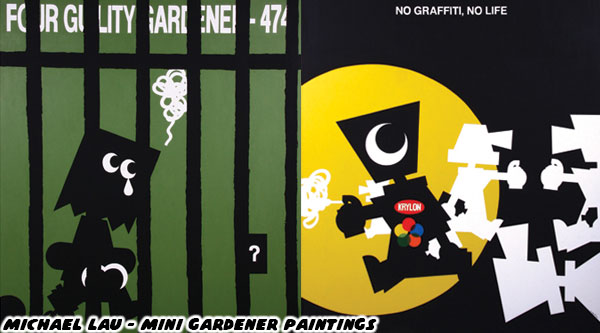

In the previous entry of this series I talked about how context changed the way I thought about the artists following on the heels of Michael Lau, and his figure art. I argued that some creators were helping spread the art form. They understood the elements that made Lau’s work unique. They were creating highly-detailed 12” figures inspired by a certain subculture. Lau had street culture covered, Brothersfree highlighted industrial workers, Eric So, and CoolRain were working on high profile NBA licenses. Then there were creators that I thought were exploiting the trend. People like Jason Siu, and Pal Wong seemed to be poaching the style that Lau had established, and retreading street culture as well. So what was it that made Michael’s work stand out from his contemporaries? How was he able to put so much context in his work that it could be understood by people around the world? It actually had a lot to do with the insight he had across a number of genres.

When I started this series I mentioned that Lau had grown up in a culture that celebrated the East, and the West. He read comics, and manhua, watched cartoons, films, and TV from all over the world. As a kid he played with handmade toys, bootleg kanji, action figures both the 12” and 3.75” sizes, and also Playmobil. These things stayed on the shelves of his work studio, continuing to inspire him as he cranked out figures, and comics for East Touch magazine. He also played sports; futbol / soccer specifically, and was good friends with a number of musicians. All of these things influenced his tastes, and by extension his style of art.

The creators that rubbed off on Lau, and his contemporaries were people like Matt Groening (the Simpsons), Jamie Hewlett (Tank Girl, Gorillaz), Simon Bisley (Lobo, Judge Dredd), and Mike Mignola (Hellboy). You could see their influence on Lau, his contemporaries, and even the modern crop of toy, and game designers. I would argue that Lau was a member of an entirely new wave of creators that came into their own in the 1990’s. Lau was a little kid when comic books started becoming stale. Publishers tried a lot of things in the late ‘70s / early ‘80s to grow their base. Including focusing on comics inspired by toy lines, such as G.I. Joe, Transformers, and even lesser know lines like US-1, and Team America.

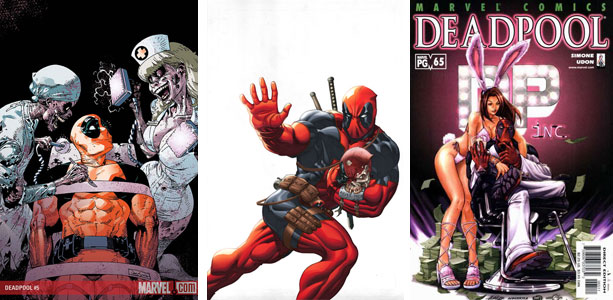

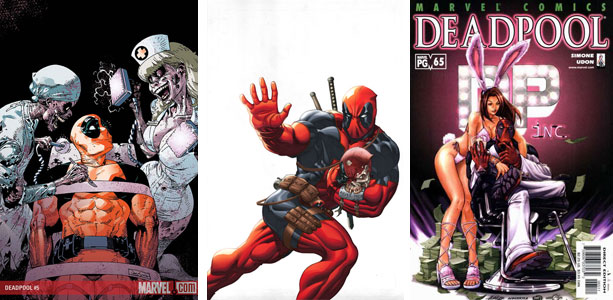

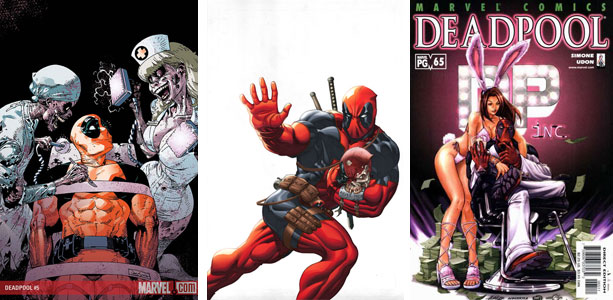

These changes happened when Generation-X was learning to appreciate the art form. The Gen-Xers going to grade school were told that in order to work at Marvel, or DC they had to follow the house style of the artists that came before. These included luminaries like George Perez, John Byrne, and John Romita Sr. The thing was that the style guides hadn’t evolved much since the ‘60s. According to the publishers it was hard to break into the market if your style didn’t conform. By the end of the ‘80s it was apparent that the opposite was true. The most popular books were drawn by artists who drew vastly different from the old guard. Even the leading characters were radically different than what came before. For example the anti-heros, like Deadpool rose to prominence.

People like Jim Lee (X-Men), Rob Liefeld (X-Force / Deadpool), Whilce Portacio (X-Factor), Todd McFarlane (Spider-Man), and Dale Keown (the Incredible Hulk) not only threw the style guides out of the window, they also rewrote the rules of the industry. They broke away from Marvel, and founded Image comics. Along with Dark Horse comics there was a place to turn to if your style was not a fit at Marvel or DC. The big publishers had to push the envelope in order to keep up with the new school. Although their young stars had jumped ship, the publishers they left behind had to update their IP in order to remain relevant with readers. The artists that they picked up to replace McFarlane, Lee, or Keown had to mirror their style at the very least. The big publishers also added new artists that brought that same outsider spirit with them. Simon Bisley’s run on Lobo for DC, and Mark Texeira’s run on the Ghost Rider for Marvel were every bit as mature as what audiences wanted from the Image books. Their contributions to the industry were just as important as the best indy creators from the ‘90s.

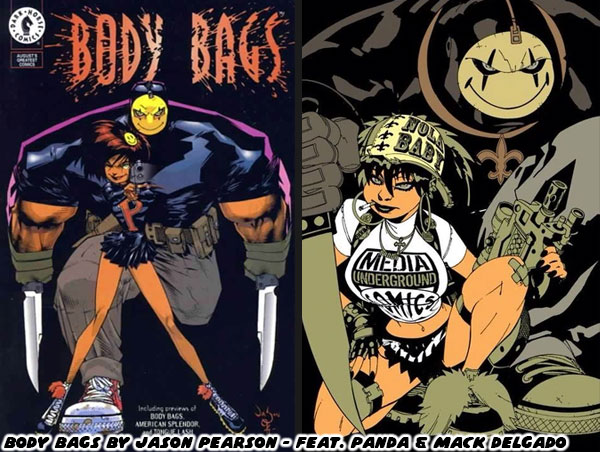

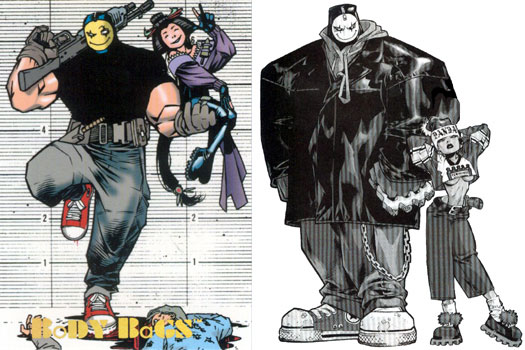

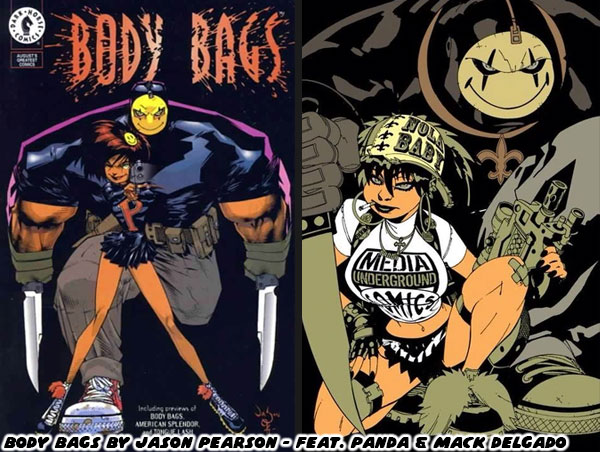

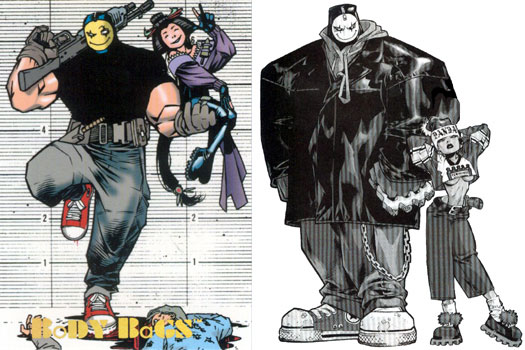

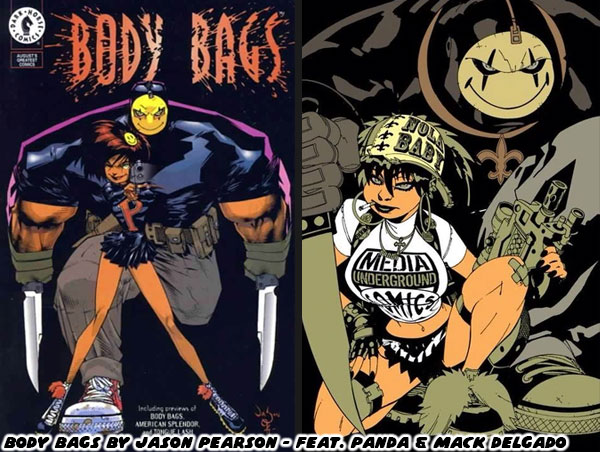

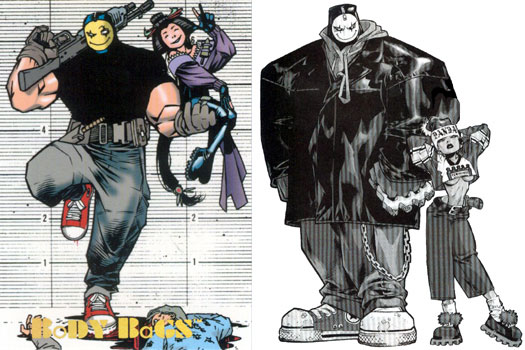

The Gen-X comics themselves were new takes on various genres. Violence, drugs, and sex had never been front, and center in the classic hero books. The new titles like Youngblood, Wild Cats, the Pitt, Spawn, Savage Dragon, and Wetworks could be adult, silly, serious, satirical, and everything in between. The books also evolved as the Gen-Xers got older. That wasn’t the most important thing this new batch of creators put forward. Minority characters finally got the spotlight in the ‘90s. People tend to forget that Spawn who was arguably the most popular of the new characters, was a Black mercenary before he died, and got his powers. Urban heroes, and villains, Asians, Latinos, Blacks, and Natives were more than token characters in the team comics. Every ethnic group started having more dimension, and gravity than in the previous decades. One of my favorite creators was Jason Pearson (Rest In Peace). His art was refreshing. He took aesthetic cues from manga, cartoonists, and most important video game artists. Contemporaries in a similar vein included

Francisco Herrera,

Joe Madureira, and

Humbero Ramos.

Many of the aforementioned artists demonstrated that pulling cues from overseas anime, and manga could be appealing to western audiences. Pearson’s breakthrough series was Body Bags. The series was first published by Gaijin Comics in 1996. It was arguably the most controversial title of the decade. It featured Latino anti-heroes Mac “Clownface” Delgado, and his daughter Panda. The style, fashion, and cultures that he featured in his dystopian world were a mashup of all things that Pearson enjoyed. His books were equal parts Punisher, Quentin Tarantino, and

Cholo gang culture. This mentality of going “all-in” on your art was embraced by a lot of creatives in the ‘90s. They were remixing, and sharing the cultures that they loved to an entirely new fan base.

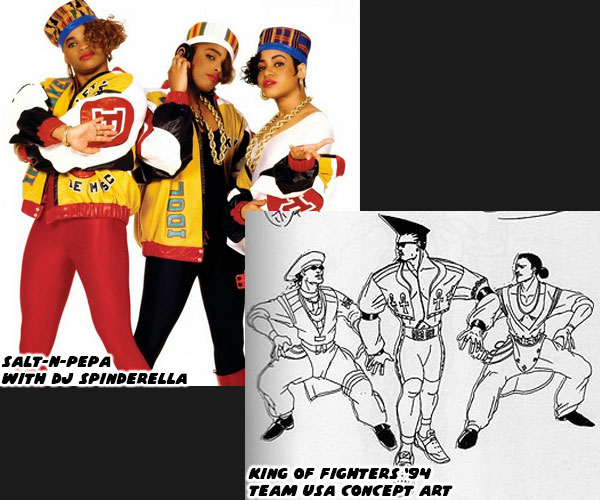

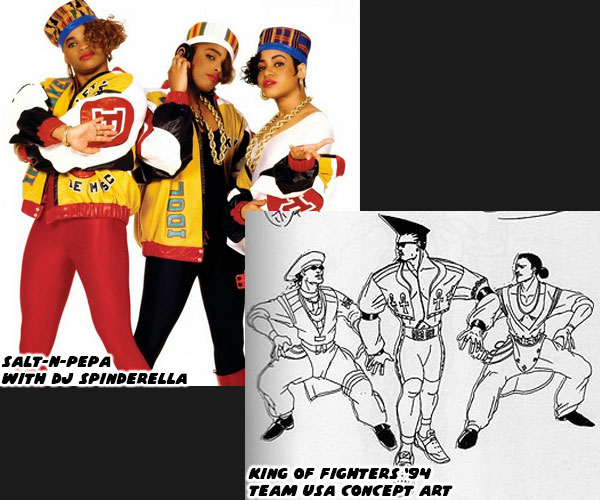

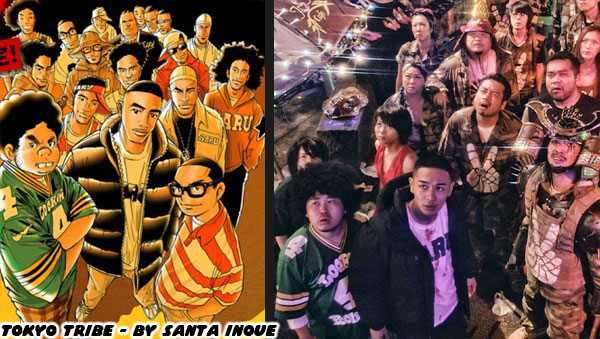

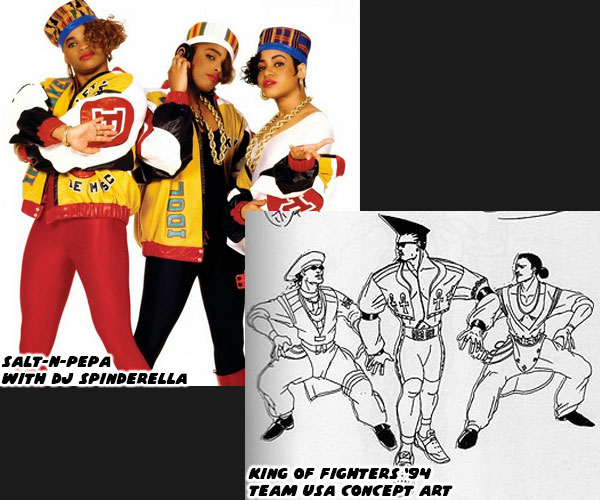

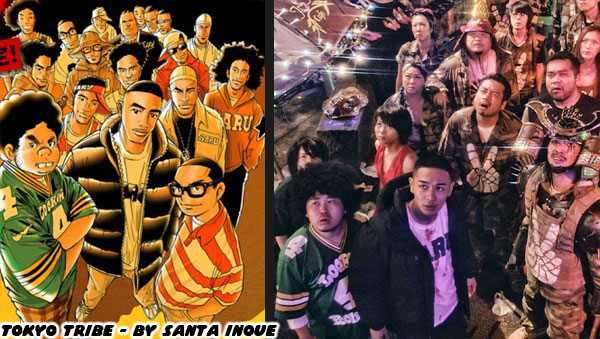

In Japan there were also phenomenal creators like Santa Inoue. His Tokyo Tribe manga series debuted in Boon magazine before it was serialized. Tokyo Tribe would eventually become animated, and even get a live action feature. Inoue used Hip Hop culture as the backdrop of the story revolving around Kai, his Saru gang, and their battles against rival gangs; Waru, Hands, and Wu-Ronz. He kept his stories grounded to the streets, and his heroes fought with their fists (and baseball bats) where other titles featured heroes that relied on magic, super powers, or psychic abilities. The heavy, and violent tone of his books captured the angst of a new generation of Japanese kids. They identified more with western Hip Hop, than with traditional Japanese culture. This poured into every element of pop culture in Japan, including fighting game character designs.

As entertaining as the Tokyo Tribe comics were, they also served as a primer to introduce adults into this world that was shaping street culture before their very eyes. Mr. Inoue had grown up listening to rap, and watching music videos from the west. He was well versed in the four pillars of Hip Hop, and his attention to detail, and remixing of cultural brands was extremely well done. Michael Lau ended up

doing a crossover with Tokyo Tribe, and releasing some figures as well. Lau, and Inoue were prominent creators putting their passion for street culture front, and center. The Hong Kong toy community in the late ‘90s, and early 2000’s were as revolutionary as the Image crew was to the US in the early ‘90s.

In the US it wasn’t a straight line to get urban art turned into collectable figures, but there was a change happening. Spawn creator Todd McFarlane would go on to build

an epic toy empire. He could tell that the quality of action figures had been lacking in the US for some time. Fans of his comics were growing older, and they wanted to collect more than just books. So he formed his own company, and had steadily raised the bar by releasing highly detailed, quality figures over the decades. He also licensed movie, game, and pro sports franchises for his catalog to great success.

It was apparent that as they got older Gen-Xers were really into collecting toys, and figures more than any previous generation. This understanding was embraced by Lau, and his contemporaries. By turning the figures from his comic book run into art gallery presentations Mr. Lau was able to elevate the form in the eyes of the international community. This was not a fad, and this was not a hobby. Urban vinyl could be as legitimate as any print, painting, or sculpture from established artists.

Of all of the figures that Lau created, and released, it was the athletes that got the strongest reaction from me. I’ll talk about it more in the next entry. For now I’d like to know if you were a fan of the comics, or toys from the ‘90s. Was there a particular culture that you identified with? I’d like to hear about it in the comments section. As always if you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment