SCUD Race and Daytona USA 2 introduced the art of storytelling to arcade racers. Prior racing games had a mix of design concepts. Whether the course was based on a real location or was entirely a work of fiction there were elements that would come up again and again. Circuit based courses, those that required players to do laps, often had some interesting scenery along the way. Perhaps it was some skyscrapers or a bridge off in the distance that drivers would eventually go through. The various points along the course were sprinkled with unique touches, Perhaps a racer would drive past a gas station, small village or windmill. Namco had done an exceptional job of creating these types of circuits in the Ridge Racer series. The details they put into each course helped ground the racer into the world that the studio was trying to create.

Then there were the racing games that were stage based and had cars going for distance, like OutRun or Dirt Dash. These games had rapidly evolving landscapes and sometimes terrain to constantly challenge the driver. These places might feature actual landmarks or invent virtual ones. Each stage on the course was like a mini circuit. All of the supporting details would help create a theme for each stage. Just as soon as the player got settled into one location however they would be entering an entirely new one. This kept racers engaged more than most circuits but from a design and a development standpoint they were also more difficult to pull off. What Sega did was strike a balance between circuit design and stage design. It was presented very well in SCUD Race and Daytona USA 2. In the previous blog I highlighted how the 90's Arcade Racer was an homage to these types of games. Earlier 2D and 3D racing games often did feature strong cohesive themes and dynamic scenery but none could match the splendor of the games built on Sega's Model-3 hardware. The

Mystery Ruins in SCUD Race told a story. It was the next logical step for race game design.

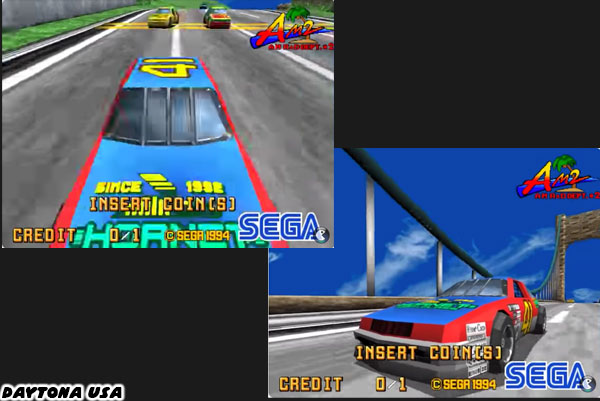

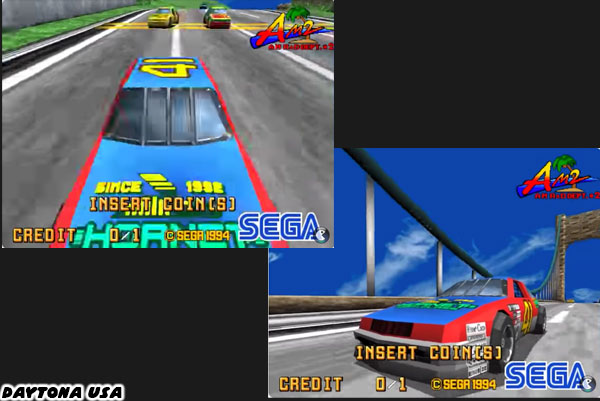

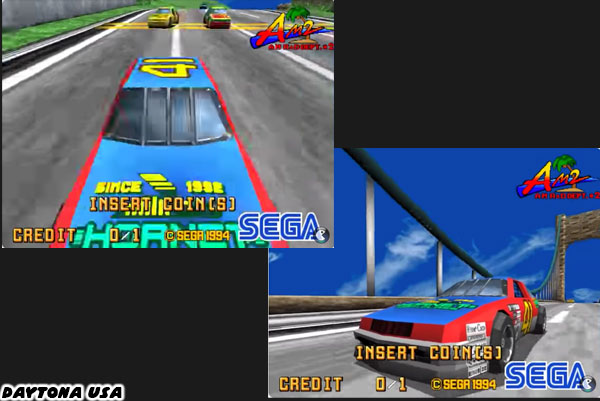

The teams at Sega were tasked with coming up with convincing 3D worlds and in order to do that they had to learn the art of storytelling. The game had to communicate an idea as a player approached it. The shape of the cabinet, graphics used, colors assigned to it had to be done with some forethought. If a cabinet were painted in bold colors with racing stripes and sponsor stickers then there was no doubt what the game was about. If a cabinet had minimal color and no logos and players did not see a steering wheel right away then it could be about anything. The game itself then had to continue the narrative. The types of cars a game featured, the types of courses players could choose from all worked into the theme.

Even without saying a word many racing games left indelible marks on the art of storytelling. The Mystery Ruins for example were a sort of impossible circuit that worked within the context of the game. My brothers commented that it would be the type of a course that an Indiana Jones racing game would feature. No nation on Earth would actually allow super cars to race within ancient temples. Yet within the game there were no grandstands, no adoring fans and no cheerleaders on any course. AM2 wanted to create a pure experience between driver and course. Every turn on the course shed a little more light on the world of the Super-GT cars. The ruins were on the edge of an old town, far from prying eyes. Yet these ancient locations had roads paved through them to connect the villages. The racers were welcome to drive through the course as fast as they could.

The developers at Sega had become comparable to the Disney Imagineers. Those were the artists, engineers, programmers and composers that dreamed up the attractions and helped execute the ideas in the theme parks and cruise lines. What many teams in the game industry did was very similar, except they were creating virtual theme parks for gamers to enjoy. Instead of a theme park attraction players could visit an arcade where they would sit inside deluxe cabinets that sometimes moved as well. Many of the best designers at Sega were tasked with creating theme park experiences in the Joypolis arcades which Sega ran. Many of the attractions that they created were like interactive dark rides. They carried the experience of attractions back to their arcade hits. The studio discovered that racing games were perfect tools to help create a narrative.

A racing car was like the Disney "Omnimover." It was a dark ride on a track that pointed audiences in the direction of a scene. It would turn and continue pointing riders at the next scene in the narrative of a particular attraction, like the Haunted Mansion. For Sega the challenge was in creating an interesting scene on every part of a racing course. The team at AM2 learned to use buildings, tunnels and scenery to block out parts of the course until it was the right time to reveal them to players. In this way something could always "pop out" at the right time. Each course was built with so many unique elements that several laps was not always enough time to catch all the details. Just like a great dark ride there was always a reason to keep going back.

The

Joypolis 2020 track featured in Daytona USA 2 could be considered one of the best, if not THE BEST racing circuit ever created. Who else but the team at Sega would think to put a racetrack through an active theme park? Note that I said Theme Park rather than Amusement Park. There was a notable difference between the two. An amusement park could have a collection of thrill rides, dark rides and games that did not necessarily fit together. A theme park featured the same ride elements however they all shared a particular theme. Even the gift shops and restaurants in a particular area held closely to the theme. With multiple distinct areas Disneyland would be a perfect example of a theme park whereas a Six Flags Magic Mountain was a collection of roller coasters that did not always complement each other, hence making it an amusement park. The Joypolis 2020 stage featured multiple themed areas including a haunted house, space port, western canyon and arctic exhibit. The stage was gorgeous and the eye candy that Sega provided would influence countless racers, even those that did not feature cars, like Hydro Thunder and H2Overdrive.

It wasn't simply superb graphics, car type, gameplay or course layout that made the Sega games memorable. It was all of those elements combined by a narrative that propelled players forward. The right car on the right track at the right time tuned the arcade racer into a cinematic experience. No words needed to be said, no plots needed to be laid out. The machine and the driver were united, the car had replaced the mascot in the best games. It was experience that could be enjoyed universally without relying on words to tell the story. Just as the arcade racer had reached a creative peak however it would soon disappear. The home console had been leeching players away from the arcade for years. When home consoles began the shift from 2D to 3D graphics engines in the mid '90s it would only be a matter of time before visiting an arcade would become a thing of the past. The racing genre was a staple for every generation and many of the early 3D console hits were ports from the arcade. There was one series of racing games that seemed destined for the consoles. It did so well that it would outlive the competition. Interestingly enough that series did not belong to Sega. The next chapter in this blog goes through the evolution of a series, starting from scratch. I hope to see you back for that.

As always if you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

Good series nice job camparing the two companies racing histories.

ReplyDelete