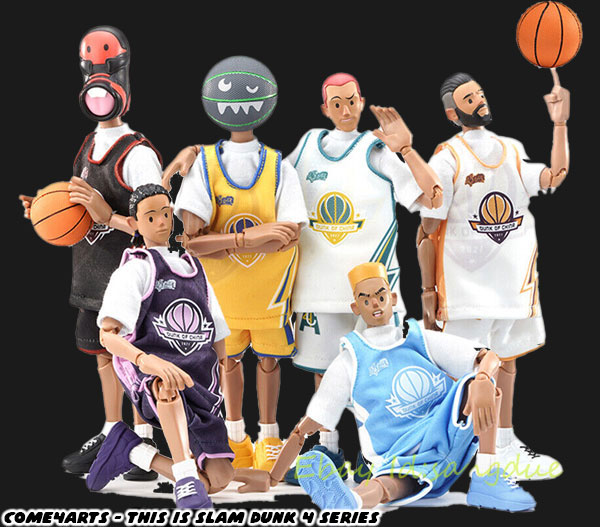

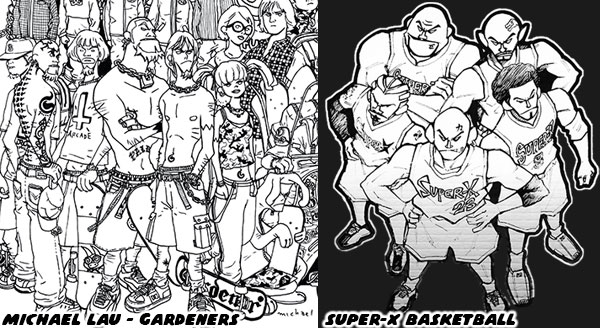

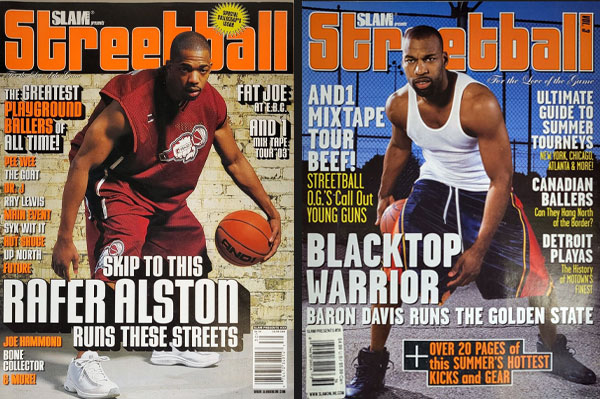

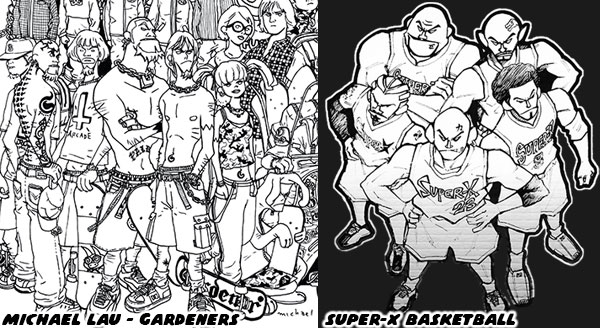

This series started with me declaring how much I loved basketball. I was never any good at playing it, or any sport really, but I liked writing about it, and I really loved drawing fictional streetball characters. I’m still a huge fan of the game, and still get inspired when I see basketball art from various illustrators. I also talked about how Michael Lau came along at the end of the '90s, and turned me into a fan of urban vinyl art. I collected many of Lau's mini gardener figures before the trend took off. Many of my other favorite toys were streetball vinyl players. The Super-X line of fictional players inspired by actual NBA legends meant a lot to me. That collection from Dragon Models out of Hong Kong, and the Upper Deck All Star vinyl figures from the US were among my prized non-Lau figures.

NBA Street debuted in 2001, not long after the urban vinyl trend was started. Developed by EA BIG it brought together stylized character designs, streetball which had looser rules than pro basketball, and arcade game play. There hadn't been anything that had captured the frenetic pace of the game since NBA Jam from a decade earlier. There were several reasons why NBA Street really stood out to me. Of all the sports it was the one the closest to the playground experience. It was created on a farm in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1891, but in less than 50 years it would become the most important game of the inner-city. It would be embraced by black, and brown kids faster than any other sport had ever done in the history of the US. Even though the NBA didn't integrate Black players until 1950, it was nonetheless following on the heels of Major League Baseball which started integrating in 1947.

There were many Black pioneers in the ‘50s, but it wouldn’t be until the late ‘60s, and ‘70s that Black culture really started showing up with the players. The Civil Rights era turned athletes into cultural touchstones. This meant that the music, the language, the fashion, and even the hairstyles of the street also became part of basketball culture. This made it easy to identify with the sport while growing up in the city. Unlike baseball, or football, the game of basketball didn’t really need a huge field, just a basketball, and a hoop could do the trick. It didn’t matter if it was a hoop on a garage, or a milk crate tied to a telephone pole. The game was easy to pick up, and impossible to master. Every time you played you could learn something new. The athletes that played the game, the culture lent itself easily to urban vinyl art. The best figures in my opinion reflected the world. They weren’t trying to sell a name, or brand.

While growing up the toy companies told my brothers, and I season, after season what we were going to play with. The cartoon shows they produced were nothing more than extended television commercials. By Christmas time their goal seemed to get us to dump all our old toys, and beg our parents for some new ones. These manufacturers reminded us that there weren’t any alternates, they controlled the toys, they controlled the games. Even Legos which were the standard for letting kids use their imagination soon started licensing movies, and comic book franchises. Countless generations were stuck following the same trends. All of that changed when urban vinyl figures made their debut at the end of the ‘90s. These toys were not selling any product, or label necessarily. They were instead a celebration of us. There were men, women, boys, and girls that looked like us, our family, our friends, and heroes. They highlighted our culture, our music, and fashion. More than that these figures just looked cool. This understanding started changing the way that characters would be designed for video games.

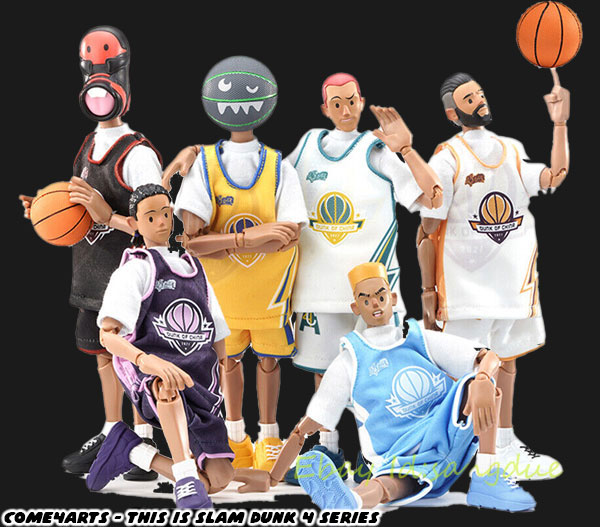

JC Entertainment out of South Korea started creating streetball games in 2004, and continued pushing the genre forward over the next 20 years. In the earliest days they presented traditional street-styled basketball players, with jerseys, shorts, and sneakers. Over time their ball players would become more stylized, and dress in all sorts of outfits. They played in business suits, track pants, surf gear, astronaut helmets, pajamas, and much more. By the time they released 3on3 Freestyle in 2016 the studio had fully embraced vinyl character design. I enjoyed the look of many of the characters that went into their franchise. Joey was the star player, and had received a radical makeover called “Intensive Joey” for a special update. Of course it was absurd that anyone would try playing in boots, neon purple, and green punk rave gear. It nonetheless was a hard look. The fact that he was pictured with a black spiked basketball brought the entire fit together. It made me wish that JC Ent. made collectable figures, and not just virtual characters. It also got me thinking of what was it that I really enjoyed in those designs, in basketball, and vinyl figures.

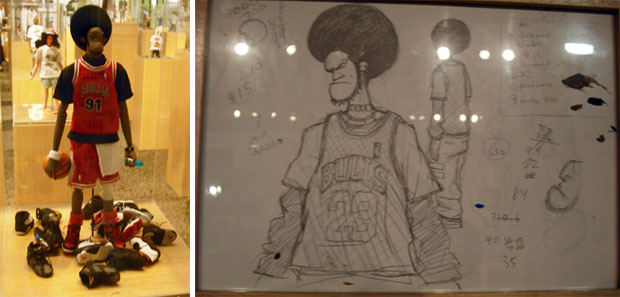

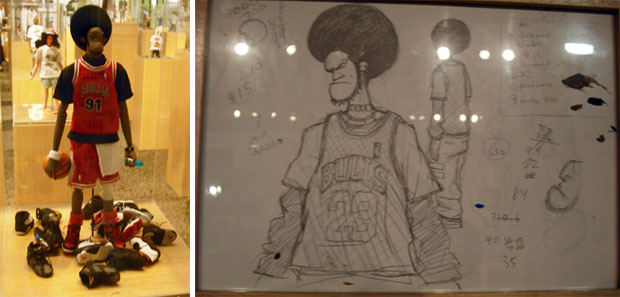

I talked a little about it previously on this blog series. As much as I liked the game of basketball, and as much as I admired the superstars, I just wasn’t invested in getting highly detailed 12” figures of those players for my collection. The more stylized they were, like the All Star Vinyl line from Upper Deck, the more likely I was to collect them. But there was a different motivation to which figures I sought out. I liked characters that represented an era, a genre, and entire league even more than an individual player. In my opinion the greatest gardener figure designed by Michael Lau was Jordon. He was more than just a clone of Michael Jordan.

For starters he didn’t look anything like Mike. He was much taller, with a large afro, earring, and eyebrow piercing. He represented the entire game of basketball. He was a snapshot of the late ‘80s / ‘90s era of the professional league. This would be during the formative years of Michael Lau, when the street influence was inescapable. We're talking a period of time when all the classic Nike commercials from "Just Do It," and "Be Like Mike," all the way to "

It's gotta be the shoes" directed by Spike Lee (as Mars Blackmon) had taken place. This marked a time when Hip Hop, and pro basketball started going hand-in-hand.

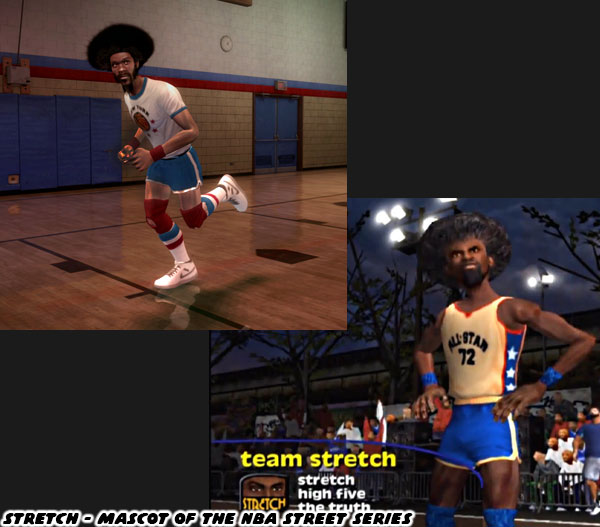

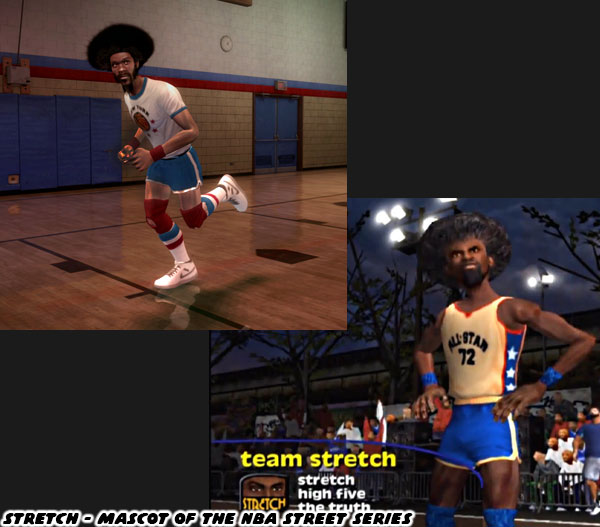

These street-centric campaigns were an affront to the loud protests of the team owners. They wanted basketball players to be seen as clean-cut college kids gone pro, and not street kids hitting it big. By the late '90s, and early 2000's Hong Kong was the only place on Earth that understood how to tie all of those cultural touchstones together into a new 3D format. They had a culture that was quick to spot trends, remix them by pulling elements from music, fashion, and street culture while creating their stylized vinyl figures. Their ability to remix culture at an absurdly rapid pace would end up changing the way studios the world over would approach their own character art. This sort of stylized representation was what I thought made Stretch Monroe from the NBA Street franchise so important. Although he was modeled on the ‘70s era Dr. J, he represented much more than that.

Stretch was a fictional legend from the same post-Civil Rights era. He was like many of the pioneers of the rival ABA that were pushed out of the league when the NBA captured the market. He just couldn’t fit in because he was too ahead of his time. Stretch never got a chance to compete in the pro ranks. This didn’t stop him from destroying all challengers on the playground over the following 30 years. When NBA Street 2 came out, and EA Big started putting retro characters in the game, like a young Julius Erving then it made the inclusion of Stretch feel redundant. The fictional spirit of basketball was the aesthetic that I loved more than anything. I wondered if there was anything that a new generation of creators could do to make me rethink my approach to collectables, and specifically their basketball character designs. Could I ever love a design for a real world player as much as I loved the fictional Stretch? What about his fictional contemporaries? All9Fun had the answer for me when they released Basketrio.

In case you weren’t familiar with the current generation of pros, the ones featured in the picture above were based respectively on Giannis “The Greek Freak” Antetokounmpo, James “Fear the Beard” Harden, LeBron “King” James, and Joel “The Process” Embiid. All9Fun allowed you to create your own avatar, build stats, earn prizes, and unlock pro players. These were things that gamers had already seen for years. However the pro players, or rather look-alike pros were not licensed from actual NBA, FIBA, or other leagues. Despite being eerily similar to real people the studio changed just enough features on them to skirt IP laws. The case of public opinion was something else entirely. It was similar to how they released players based

on Street Fighter designs. I highlighted them in the previous blog. The team at All9Fun were building virtual characters using all the same tricks that Fools Paradise did when creating

the Three Kings, and TwentyFour statues I had also talked about. The thing was that the statues from Fools Paradise, and the virtual characters from Basketrio were extremely desirable to fans. They managed to capture the personality of some of the greatest players to have ever existed, but in a highly-stylized fashion.

As a fan of the vinyl aesthetic there was no doubt that the design worked in video games. Basketrio featured a version of the NBA elites in a format that I had always wanted to see. It was as if the studio was able to pull equal parts of the animated look of the Upper Deck All Star Vinyl figures, the street fashion sense of Michael Lau’s gardeners, and

the Hong Kong style of the Super-X athletes. The remix of the various elements was sublime character design. The knockoff pros featured in Basketrio were a master class in storytelling, and streetball design. First off the team understood the scale of the individual players. The largest of which was “Shark” who was based on Shaquille O’Neal who in real life was over seven-feet tall. The smallest of which was “The Answer” who was based on Allen Iverson, who was barely six-feet tall.

Everyone in between had a cartoonish scale applied to them. Their frames, muscles, shoulders, torsos, hands, and feet were just a bit exaggerated. This helped the characters stand out from the rest of the cast. As with fighting game characters, the bigger hands, and feet were easier to read when moving across the screen. They allowed animators more leeway when creating movements for crossovers, backing down opponents, and of course flashy slam dunks. These proportions also made it easier to read dribbles, or passes, making defending against them more balanced for gamers. From head to toe their costumes were absolute works of art. There was more to the fit than would be typically seen on a streetball player. They were all essentially wearing high fashion streetwear, however the choice of colors, logos, patterns, also reinforced the personalities they were portraying. NBA fans could identify who these characters were based on just by looking at their faces, however the studio could get away with it because they never named one of the characters after an actual person.

All9Fun skirted the line without ever crossing it. For example Shaq was called Shark, Kobe Bryant was called Mamba, after his nickname the Black Mamba. The outfits they wore had similar colors to their actual team uniforms, of course nobody could copyright a color combination, nor could they copyright the name of a city, initials, nicknames, or even numbers. Even if each of these things happened to be pulled from actual players, and teams. This allowed the staff at All9Fun to dress the characters appropriately, without getting in legal hot water. The outfits of each, and every player was more than really fashionable street wear. They were the streetball equivalent of superhero uniforms. Fans of every sport tended to make icons out of their favorite athletes. Even race car drivers, and their autos enjoyed a certain level of hero worship. Fans of

NASCAR could tell you how important the colors of their favorite cars were. Just as red, and blue were matched to Superman, or red, and yellow were matched to the Flash every character in Basketrio got similar nods.

The Lakers royal purple, and gold were matched to Kobe, and Lebron’s outfits, without either of them wearing anything remotely alike. The Milwaukee Bucks forest green, and white dressed on Giannis. The Maverick’s navy blue, silver, and black were placed on Luka Dončić. Even if you had no idea which teams, or players they were based on, each of the outfits was inspired. The standout was Dennis Rodman, the long-retired former Bulls player had multicolored hair, was shirtless with a feather boa, and dressed in white pants with the words THE WORM printed on the leg. A nod to his

over-the-top personality, and outspoken fashion sense. While I could never justify spending hundreds on realistic NBA figures, if any studio were to ever release 12” collectables in the vein of the Basketrio characters then I wouldn’t hesitate to get them all.

I was extremely happy with my Super-X team, and the Vinyl All Stars. They sung to all of my interests in a way that no other creator except for Michael Lau was able to reach. I never thought that anything better would come along. All of that changed fairly recently. A figure designer learned the tricks that the artists working on the FreeStyle Street Basketball series were using. Not only that his work predated the look of the Basketrio icons. I will talk about this designer in the next, and final blog in this series. What do you think of video games using the likenesses of real people, or teams without licensing them? Would you be willing to look the other way if they spoke to your interests? Do you think there is a difference behind art, and IP theft? Where do you draw the line? I’d like to hear your thoughts on the comments section. As always if you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs, podcasts, or buy a future streetball figure!