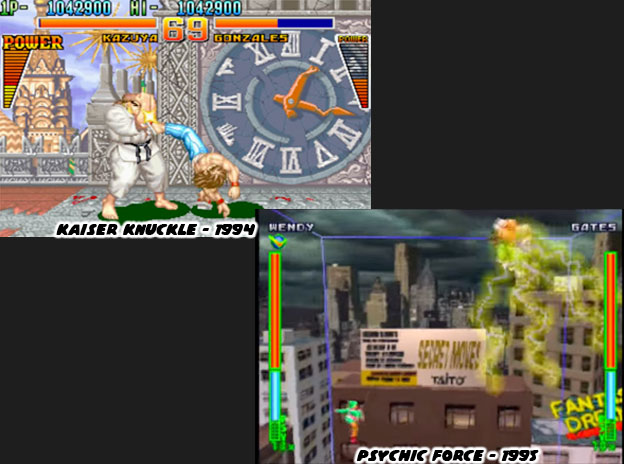

Taito was no stranger to the fighting genre. In fact the studio could be considered The Godfather of the brawler. It released Renegade in 1986 and Double Dragon in 1987, both of which had a profound influence on the industry, and especially Capcom. The studio had created a traditional sprite-based fighting game called Kaiser Knuckle in 1994. Yet their most revolutionary work came one year later with the released of Psychic Force. This new game featured a 3D engine and characters that could fly in all directions. and different formats and engines. A few years had passed since they had made a serious entry into the fighting game arena. What no one expected was a fantasy title with is much depth as Chaos Breaker.

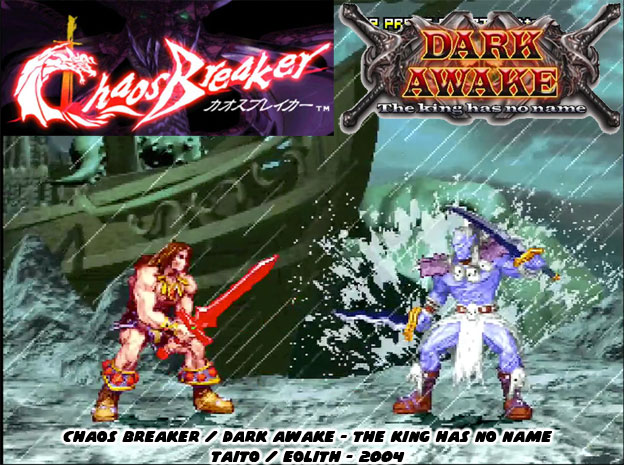

The game was actually developed by a South Korean studio called Eolith. The studio had experience with one of the biggest franchises of all time. They developed the King of Fighters 2001 and 2002 after SNK went bankrupt. The 3-vs-3 battle system of KOF was carried over into Chaos Breaker. As SNK restructured they needed help keeping their IP afloat. This was when they began talking in earnest with not only South Korean developers but also Chinese publishers. Chaos Breaker was the last game by Eolith before they were acquired by NetBrain. The game itself was the first fighting game to take advantage of the Taito Type-X board. A lot of different arcade titles were developed for that board including properties like Mobile Suit Gundam, Half-Life 2, and Pokémon. None of the games was remotely close to Chaos Breaker.

Part of the reason that Chaos Breaker stood out was because of its graphics. The visuals were similar to the graphics used in early ‘90s fighting games, including Killer Instinct, Primal Rage and even Mortal Combat. The reason for this was because Eolith used similar techniques I creating the sprites. In the early ‘90s there weren’t many 3D games, and especially not fighting games. The quality of 3D graphics that we have with titles like Street Fighter V and Tekken 7 was simply impossible to pull off almost 30 years prior. Studios did whatever they could to try to top the hand-drawn graphics featured in the most popular games. Midway experimented with video capture to create sprites out of human actors in Mortal Kombat in 1992. Atari used stop motion animation to create sprites out of clay and plastic dinosaurs that they molded for the 1994 hit Primal Rage. One of the most revolutionary games was Killer Instinct, also released in 1994. Developed by Rare the studio used high-end Silicon Graphics workstations to create highly polished 3D models and levels.

In the early ‘90s there wasn’t any arcade hardware powerful enough to render 3D visuals, complete with textures and lighting effects in real time. So what they did was create sprites out of their models. The two-dimensional graphics did not require as much storage as their 3D counterparts and the engines of the day could animate them fairly quickly. The end result for these games were the illusion of 3D figures and stages. This technology was mostly used by Western studios, so that they really stood apart from the graphics that the Japanese were creating. Almost 10 years later to the day Eolith used the same techniques and rendered characters and levels using 3D hardware but then converted those graphics into sprites. Chaos Breaker had the look of a more polished version of a classic fighting game, yet there was much more to it than that.

In the early ‘90s there wasn’t any arcade hardware powerful enough to render 3D visuals, complete with textures and lighting effects in real time. So what they did was create sprites out of their models. The two-dimensional graphics did not require as much storage as their 3D counterparts and the engines of the day could animate them fairly quickly. The end result for these games were the illusion of 3D figures and stages. This technology was mostly used by Western studios, so that they really stood apart from the graphics that the Japanese were creating. Almost 10 years later to the day Eolith used the same techniques and rendered characters and levels using 3D hardware but then converted those graphics into sprites. Chaos Breaker had the look of a more polished version of a classic fighting game, yet there was much more to it than that.

In the early ‘90s there wasn’t any arcade hardware powerful enough to render 3D visuals, complete with textures and lighting effects in real time. So what they did was create sprites out of their models. The two-dimensional graphics did not require as much storage as their 3D counterparts and the engines of the day could animate them fairly quickly. The end result for these games were the illusion of 3D figures and stages. This technology was mostly used by Western studios, so that they really stood apart from the graphics that the Japanese were creating. Almost 10 years later to the day Eolith used the same techniques and rendered characters and levels using 3D hardware but then converted those graphics into sprites. Chaos Breaker had the look of a more polished version of a classic fighting game, yet there was much more to it than that.

In the early ‘90s there wasn’t any arcade hardware powerful enough to render 3D visuals, complete with textures and lighting effects in real time. So what they did was create sprites out of their models. The two-dimensional graphics did not require as much storage as their 3D counterparts and the engines of the day could animate them fairly quickly. The end result for these games were the illusion of 3D figures and stages. This technology was mostly used by Western studios, so that they really stood apart from the graphics that the Japanese were creating. Almost 10 years later to the day Eolith used the same techniques and rendered characters and levels using 3D hardware but then converted those graphics into sprites. Chaos Breaker had the look of a more polished version of a classic fighting game, yet there was much more to it than that.

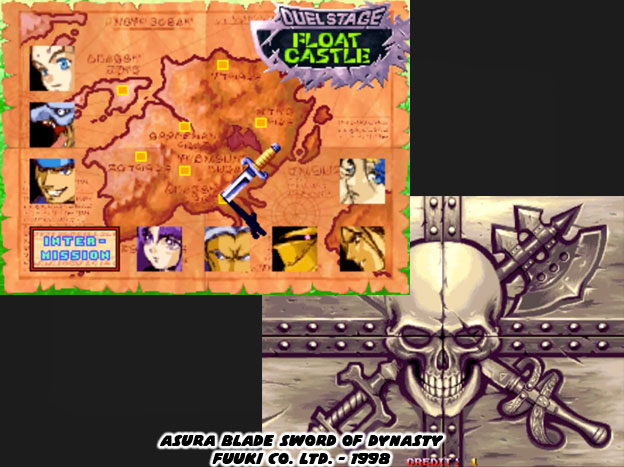

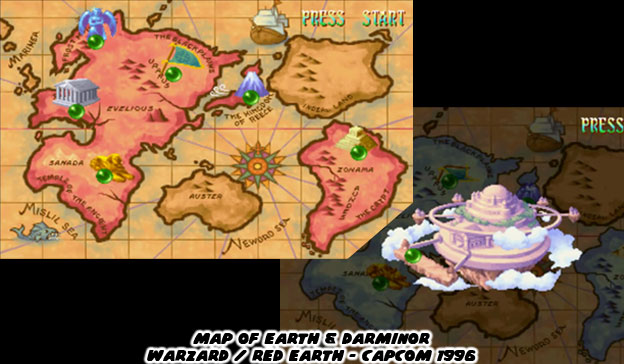

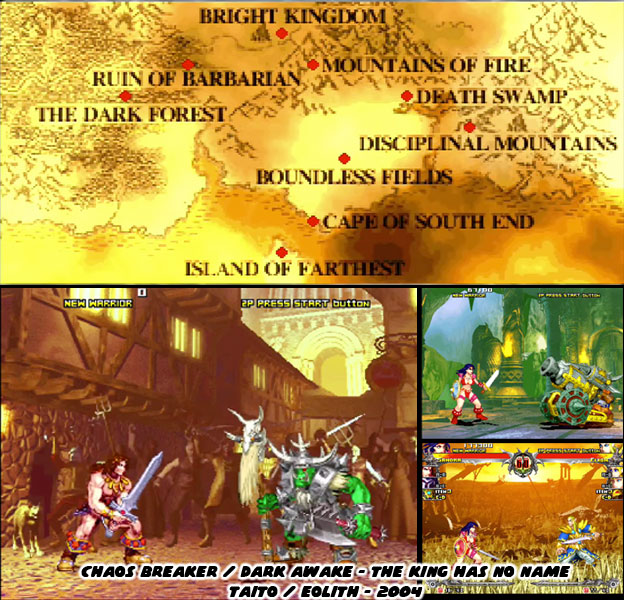

Eolith made sure to create levels that told a story. Each stage reflected the world that these fantasy warriors were trying to save or destroy. They had as much forethought as the highly detailed stages created by Sega in Golden Axe: The Duel and Capcom’s Warzard. Eolith had learned as much as they could about fantasy settings, not only in video games but also in popular culture. They made sure to apply these things in every stage of the game. If you have ever seen or played Chaos Breaker then you have probably noticed level settings, weapons, armor and character designs borrowed from animé shows like Berzerk and Record of Loduss War. Of course the publisher had not slept on the highly influential World of WarCraft, after all they were a South Korean studio. It was impossible to get into any sort of fantasy game development without drawing immediate comparisons to WoW. Eolith did not disappoint the fighting game community. They expected the major fantasy races in Chaos Breaker and they were all there. Sorcerers, barbarians, rangers, goblins, orc, elves, dark elves, necromancers and even vampires.

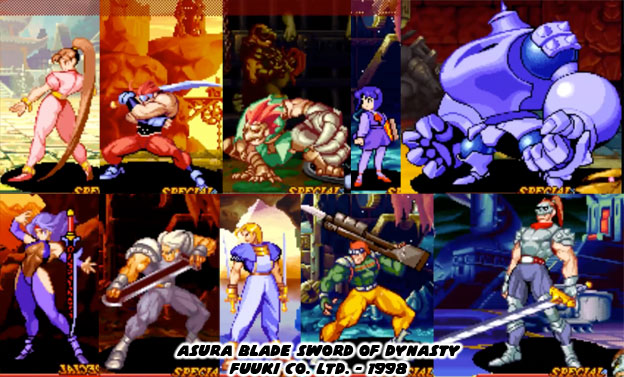

The character designs had a decidedly anime influence to them but they were not based on any one particular series. Instead they reflected the fantasy tropes that audiences were used to. Busty women that wore revealing armor, and muscular men with big swords. Villains were grotesque and clad in spiky dark costumes while heroes were handsome and wore bright colors. Eolith did more than use pallet swaps when designing alternate colors, or while porting the game to consoles. They actually created different models of the heroes and villains in different costumes to make them look truly unique. Ramda for example was a long-haired barbarian but his alternate costume gave him a haircut and had him in warrior armor.

When it came to the design behind this game the most influential studio was not Japanese nor were they American. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again and again the British studio Games Workshop was the design house most copied by video game developers. This was the company that Eolith was modeling most of their character classes after. To be completely honest Games Workshop did not invent all of the fantasy characters. They had existed much earlier in fairy tales, Arthurian legends and the works of Robert E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft, J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. Games Workshop standardized the designs of many fantasy characters and made them popular. When audiences think of goblins and orcs they imagine certain green-skinned characters in crude armor. When they think of dwarfs they think of hefty armor and ingenious artillery. When audiences think of chaos warriors, they think of horned helmets and oversized weapons. Many of these looks were popularized in Warhammer Fantasy Battle from Games Workshop over 30 years ago.

Eolith did not outright rip-off any specific character from the Games Workshop (GW) library, nor did Blizzard for that matter, but they took enough elements to make the designs more than coincidence. The roots of the Chaos Breaker designs were even more obvious as they less subtly mixed-and-matched details from different Games Workshop characters. For example the Night Goblins in Warhammer were known for riding giant spiders. But there were many types of creatures that the goblins rode, from including spiders, wolves and even toothed fungi known as squigs. Not all goblins fought with swords, some instead knew crude magics and spells and were known as goblin shaman. The developers at Eolith took pieces of the various types of GW goblins when creating their own variant. Similar things could be said of just about the entire cast. the industrious and stubborn dwarfs had been a staple of GW for decades. Eolith had a few versions of the dwarfs that actually covered several different classes. Vargan fought with a ranged weapon, a multi-shot blunderbuss. Dorgan fought with a melee weapon, a large axe. And Gerhassen II fought with artillery, a cannon.

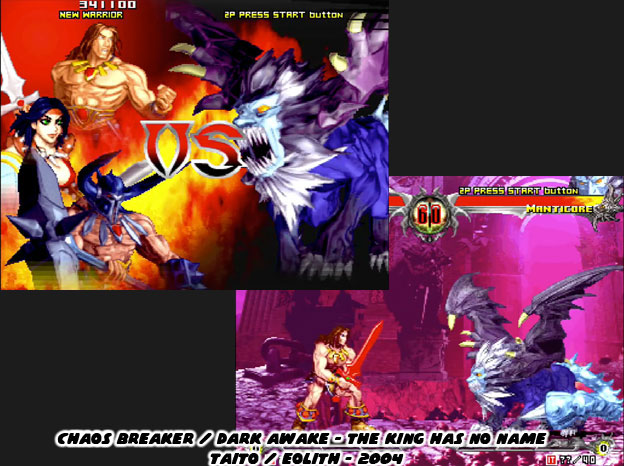

The ways in which Eolith used the characters was inspired design. Most fans of the format know they can expect a small, fast character, usually a woman. A large, slow character, usually some sort of musclebound giant. Then the hero of the game, often a guy, with equal parts speed and strength. There was a troll in Chaos Breaker that filled in the role of the giant. Yet he was not the only oversized character. For the good guys it was Gerhassen II. While his cannon took up nearly a quarter of the screen he could actually move it quickly and use it as an extension of himself. Not many studios had the imagination to turn a dwarf into the token “big” character. Just about everyone in the cast had this sort of planning behind them. The game also featured some unique boss designs. I don’t recall seeing a Manticore, part-lion/scorpion/bat that had looked as awe-inspiring as the sub-boss in Chaos Breaker.

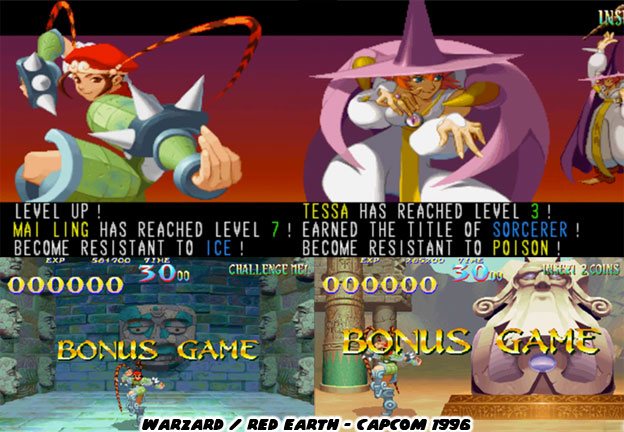

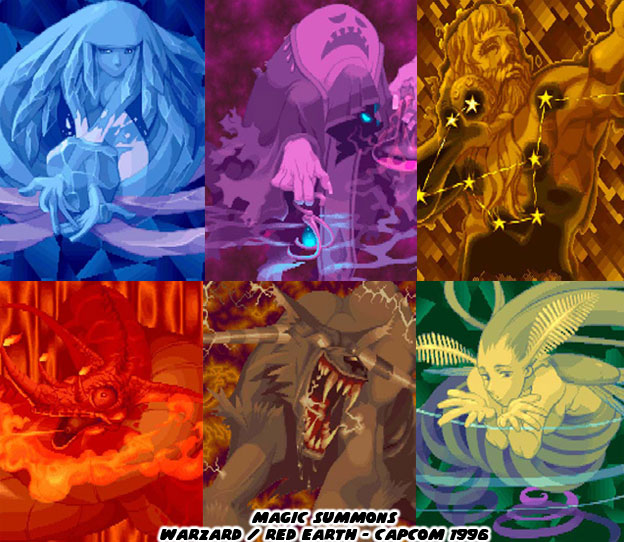

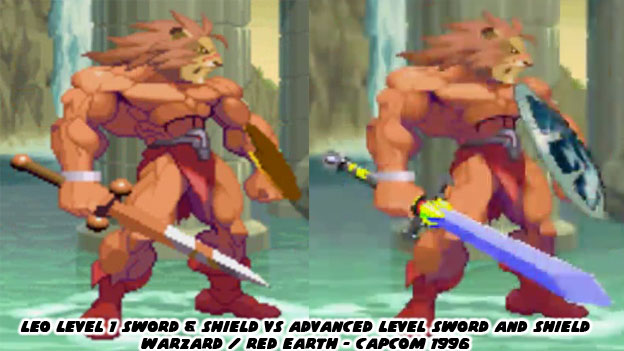

With it’s 3-vs-3 mechanics, weapons-based game play and unique characters there was still much more that Chaos Breaker had to offer. Eolith, just like every other developer that I have featured in this series, wanted audiences to fall in love with the world they had created. They hoped there was interest enough that they might turn it into a franchise. In order to do this they had to do things that few other fighting games had ever done. This title allowed players to unlock weapons, armor and other upgrades for their characters. These items acted just like their RPG counterparts. They would boost offense or defense, especially against certain types of classes and attacks. Warzard had something similar, and while leveling up did increase the health of a character or even grant them new abilities, it did not allow players to freely trade out weapons in between stages. Capcom did manage to capture a more RPG-centric experience with their Dungeons & Dragons arcade games, easily some of the best brawlers ever made, but for fantasy fighting games few could match the game play of Chaos Breaker.

The differences between character classes and customizable weapons came in handy during the final two encounters in the game. The sub-boss aside from the Manticore was a Witch Queen named Thiele. She could cast spells from afar and do physical attacks with her giant golden claw. Her appearance was somewhere in between a Vampire Countess and Dark Elf Sorceress. She floated above the ground, similar to Valdoll from Warzard, and had an equally ominous presence. Her design was simply fantastic and something that even Games Workshop would have been proud of. She was well done but the final boss of the game, the King with no name, was possibly the largest sprite ever created for a fighting game. The dragon was several screens high and had more animated pieces than the giant characters in the Capcom vs games or in any SNK game. It made for a memorable but not impossible villain.

The game succeeded on many fronts, not the least of which was originality. Fantasy fighting games, especially well made ones were few and far between. The other thing that Chaos Breaker had going for it was the net-play ability. It was one of the first entries into net arcade fighting games from Taito. The things they learned in this game could be applied in other genres, from space shooters to robot sims. Audiences might not realize that many of the things we take for granted in console fighters today were pioneered in the arcade. Some of the things featured in Chaos Breaker were never duplicated in other fighting games. Although it never got a sequel it was published on PSN in 2010.

I would recommend audiences check it out if they are interested in broadening their fighting game experience. Eolith managed to capture the epic locations that had been a staple of many great RPGs and turned them into the backdrops for a memorable fighting game. Budding artists might learn a thing or two about character design by seeing how the South Korean developers had distilled the British designs and turned them into fighting archetypes. Those interested in another fantasy action game with western influences might want to check out Dragon’s Crown, developed by Vanillaware and published by Atlus in 2013. There was one more fantasy fighting game worth mentioning that was released after Chaos Breaker and Dragon’s Crown. We’ll look at this title in the next entry. I hope to see you back for that. As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

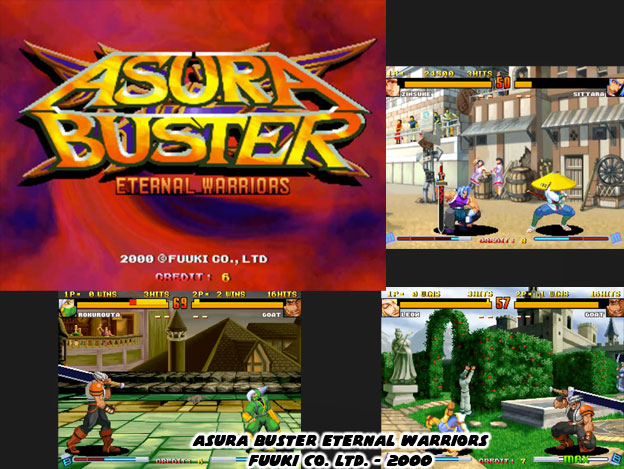

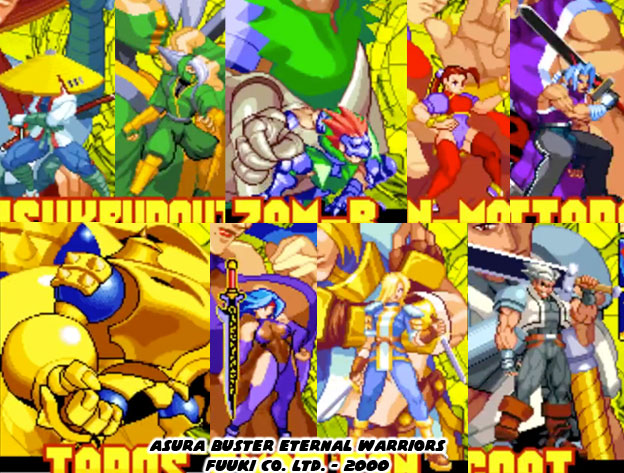

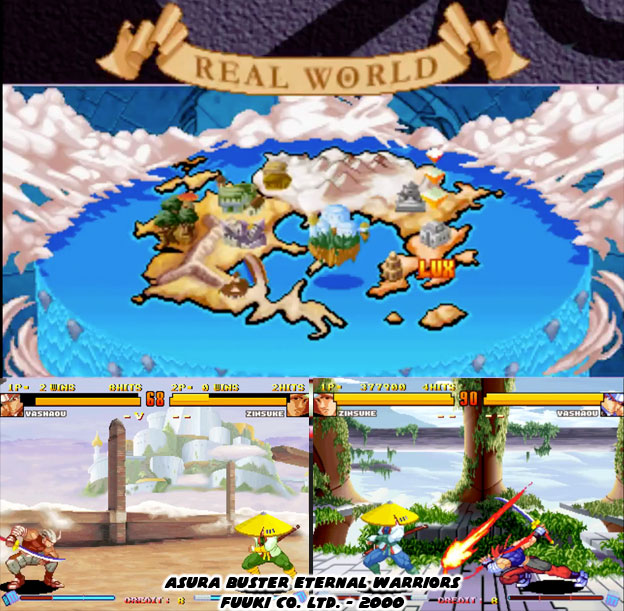

The bonus game had players fighting off wave after wave of two-headed wolves. Some ran at opponents, some leaped at opponents and some even dropped in from the sky. Players had to react quickly, a single strike was enough to beat most of them. Players couldn't die while facing the mini-cerberus, if hit the player would fall over while the dogs trampled them. Players mostly missed out on bonus points for a poorly timed session. Asura Buster was also memorable for a new sub-boss character. A large, pink, triangular, shapeshifting creature named Vebel waited for opponents in a darkened cave.

The bonus game had players fighting off wave after wave of two-headed wolves. Some ran at opponents, some leaped at opponents and some even dropped in from the sky. Players had to react quickly, a single strike was enough to beat most of them. Players couldn't die while facing the mini-cerberus, if hit the player would fall over while the dogs trampled them. Players mostly missed out on bonus points for a poorly timed session. Asura Buster was also memorable for a new sub-boss character. A large, pink, triangular, shapeshifting creature named Vebel waited for opponents in a darkened cave.