Capcom had found tremendous success with their arcade unit in the '80s. They had published more than 2-dozen hits with the original CP System (CPS - arcade board), including 1941, Ghouls'n Ghosts, Strider, Final Fight, Street Fighter and Street Fighter II. The original CPS had a long shelf life and been used from 1988 to 1995. The CPS-II was an even bigger success, having more than 40 games published for it between 1993 and 2003. Based on the success of the fighting game genre Capcom thought that they should bank on new hardware to carry them for the next decade. In the mid '90s arcade games were moving to 3D graphics and even home consoles were migrating to 3D so sprite-based 2D engines were being dropped for the most part. The Tekken and Virtua Fighter series debuted after Street Fighter II and both looked a little rough around the edges. They were improving visually by leaps and bounds with each release and would soon look better than the rehashed graphics that Capcom was using. The CPS-III would be a return to form and a chance to show that sprites were still vital to the genre. Sadly it would become the swansong for hand-drawn graphics and Capcom's reliance on 2D technology. The hardware was much more expensive to work with than earlier CP Systems. Not to mention that the genre had a lot more competition that Capcom had anticipated. Development on the CPS-III would be cut short. The engine was only used for 6 games between 1996 and 1999. Three of those games were Street Fighter III and its sequels, two were for JoJo's Bizarre Adventure and one was for Warzard.

Warzard had some of the most brilliant graphics ever seen in an arcade game. The stages, animations, effects and design were light years ahead of anything the competition was working on or would ever release. It was obvious that the publisher had gambled on this game becoming the next big franchise. Expansions were planned if not outright sequels if it became as successful as Street Fighter II. It was apparent in every detail that made it into the game. An entire world was mapped out for the audience. They were given a tour of this wondrous fantasy world in every encounter. No two locations looked the same and that was a good thing. Warzard was layered with so much detail that players were encouraged to keep playing and explore the stories of each hero.

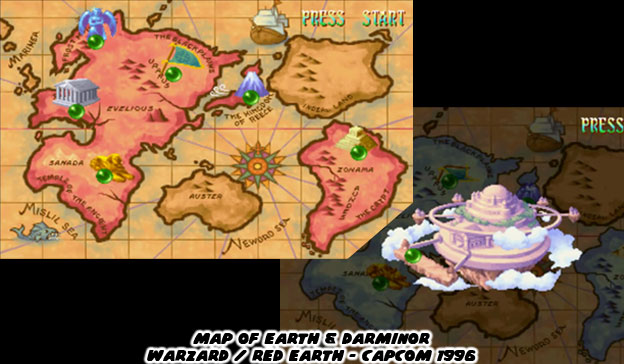

Players explored a world filled men and monsters. Technology was a mixed bag of progress and superstition; gunpowder existed alongside magic, demons consorted with nobles and humanity was at the brink of all out war. Most of the warriors fought with swords and shields but the most powerful relied on spells. Designing a visual language that was equal parts Western and Eastern fantasy required the talents of the senior designers at Capcom. They created a world where flying ships and floating islands appeared as the actual stages. I will be highlighting these people individually later on in the blog.

Every menu, on the level map, stage backgrounds and even in the title screen, were some of the most stylized graphics that had ever been seen. Capcom did not overlook any detail, even the supporting characters which may have turned up multiple times or even just one in the progression of the story had their own unique look and purpose.

These designs also applied to the villains in the game, which also came with their own cast and back story.

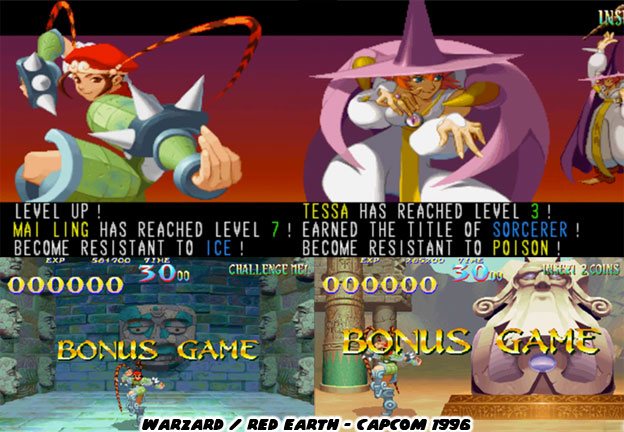

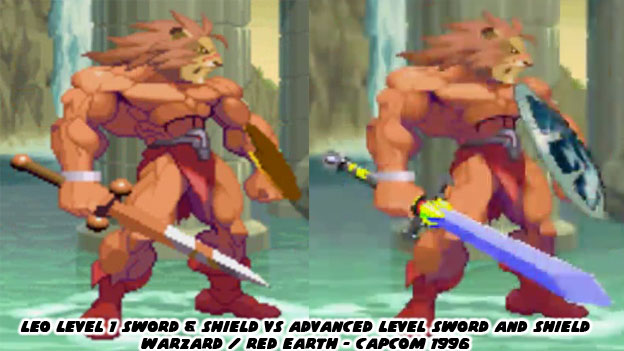

The stars of the game were four playable characters; a lion-warrior named Leo, a ninja named Kenji / Mukuro, a sorceress named Tabasa / Tessa and a young martial arts master named Tao / Mai-Ling. They each had their own strengths and weaknesses. Leo was a lion-turned-warrior. He fought with a sword and shield yet could also perform grapple moves ala Mike Haggar or Zangief. Leo lacked strong magical attacks early on in the game. Kenji had brazenly fast attacks, he had curved blades along his forearm gauntlets, a straight sword and even a cannon with an enormous gunpowder discharge. Like Leo, he was equipped to take out even the largest monster with a weapon rather than magic. Tabasa was a sorceress and had some great magical attacks. She had a magical staff that floated and she could use as a projectile. She even had a few unique physical strikes as well. Tao was a martial arts master and fought with her bare hands. She was very powerful despite her size, perhaps she was a demigod. Her kicking attacks allowed her to set fire to her opponents and throw even the largest villain across the screen. It was as if she was the ancestor that Few Long and Chun-Li were descended from.

I know that it's hard to imagine a fighting game with only 4 playable characters. It was in fact half the number of playable characters than the original Street Fighter II. Yet the quality of the sprites was unsurpassed. The size of the new characters were much larger than ever before, with a wider color palette and many more frames of animation. The animation was very fluid, better even than that featured in Vampire/Darkstalkers. The sprites were superior to the older CPS-II games. All of the extra work required for completing each character meant that less and less time could be used on filling out a bigger cast. Capcom also made sure to use design elements exploited by rival studios. This game was the first and possibly only fighter by Capcom that featured a "fatality" for opponents. If Leo finished his opponent with a strong sword attack you could actually see the villain cut in half. This includes a cartoonish representation of their brains, spinal cord and guts. It was never as gruesome as a fatality in Mortal Kombat but it was nonetheless a surprise.

Like Street Fighter II there were multiple villains and boss characters making up the lack of playable characters. Unlike Street Fighter II the developers were not required to create human opponents. They could dream up just about any type of fantastic beast to fight with. Moreover, each villain reflected the cultural that they originated from.

Take the demon Kongou for example. He was from the region of Zipang, a nod to feudal-era Japan. The stage he occupied looked very much like a traditional Japanese town, except of course that it was on fire. It was under attack from a rival army and their flying ships. Kongou was a warlord with a terrible secret. He turned into an enormous monster before the battle. With his spiked mace, red skin color and horns Kongou looked like a classic Japanese oni or demon from storytelling tradition.

Look at the multi-headed Secmeto / Ravange. This four-legged creature was a mix of Egyptian Sphinx and Chimera from Green mythology. It hailed from Sangypt / Alanbird, a desert kingdom in this fantasy world. There hadn’t been any beast as colorful in any edition of Dungeons & Dragons yet it seemed so familiar to both Western and Eastern fantasy fans. The ability to project different poisons from each head made sense and the raw strength associated with the monster was impressive, but not as impressive as the gigantic monster from Greedia / Savalia.

Hauzer was an enormous dinosaur-like monster from the home nation of Leo. It was a lost kingdom, one which had fallen into ruin many generations ago. Hauzer was a beast from antiquity, heralding a time before man ruled the Earth. The sprite created for Hauzer was one of the largest ever featured in any fighting game. He covered almost a third of the screen and his attacks could reach clear across the display. Capcom wanted to let audiences know that this game was compeltely unlike any fighting game before. Hauzer was a showcase for the CPS-III system. More impressive was that each villain was unique, with no sprites rehashed to create secondary characters.

In the frozen north there was an aquatic baddie who moved unlike any other game character. Part walking octopus, part nautilus and armed with a trident Nool was by far one of the strangest fighters ever featured in any game. He was slippery and quite fast despite his square appearance. The figure was so unique that he was placed in Capcom Fighting Jam a few years later along with Hauzer.

Luan was one of the two female villains in the game, Secmeto was summoned by a sorceress. Luan was a harpy but not the one you might remember from Greek tradition. Luan was not naked, she wore armor and had costume elements pulled from ancient China and Mongolia. She hailed from the same region as Tao, and thus shared many similar central-Asian traits. Capcom had gone above-and-beyond when it came to the color palette applied to each character. The stages were all breathtaking but seeing the quality of the animation and the size of these new sprites was light-years ahead of what other studios were doing.

Of all the villains possibly the most unique was GiGi, an animated four-armed statue. It was made of stone and had cues pulled from Pre-Columbian Central America. There was no doubt that the team at Capcom had been inspired greatly by the statue of Kali featured in the film the Golden Voyage of Sinbad. GiGi actually had a left and right side, where its main colors and even sword went from red to blue depending on which way it faced the opponent. Mind you, this was before Gill debuted in Street Fighter III.

The sub-boss of the game was an animated suit of armor called Jihad / Blade. His lance, which looked like a spinning turret, could extend across the width of the screen. In addition to being genuinely hard he had both physical and magical attacks. He could freeze opponents in a mirror and then smash them into pieces. He could also expand his armor and unleash a blast of energy from his core, a magical crystal. Blade was in charge of all the other villains in the game and was the guardian of the floating island of Darminor.

In the center of the floating island was a castle. The inner chamber had strange totems made of dark stone. Some sort of dark ceremony was taking place as the level progressed. The main villain of the game, a War-Wizard named Valdolll / Scion, was waiting for our heroes. The blue-skinned wizard wore a red robe, had long white hair and a beard. He fought with a magical staff and was flanked by two small dragons. He was immensely powerful even without the dragons at his side. When most people think of a fantasy villain a wizard doesn’t usually come to mind but this one was different. He didn’t walk but instead floated across the arena. If a player were able to defeat him once then he would resurrect himself into a more powerful form. His body turned into a grotesque shape. His head became larger, an enormous brain and spinal cord popped out of his back, multiple tiny arms sprang from his shoulders while his atrophied legs dangled from his torso. With his true form revealed it was obvious that the heroes of the game needed to destroy the monster before he could enslave the planet.

Capcom wanted audiences to understand that this was far from a traditional fighting game. It did have elements from the best fighters they had made up until that point. It needed to have the elements from the RPG titles audiences were used to. Aside from fantasy heroes and villains the game also allowed players to collect treasure from their rivals as well as in bonus stages. The characters also had a level system. The better they fought in each stage the faster they were rewarded with a new level. The levels allowed them to gain new attacks and stronger defenses.

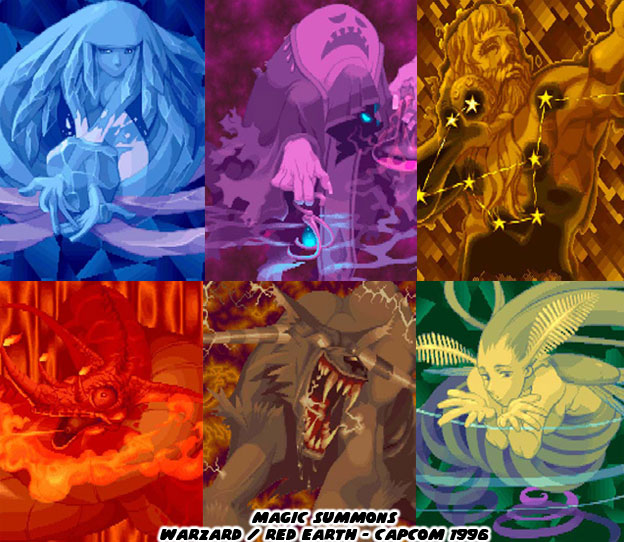

Audiences rightfully expected magic to be an internal part of the experience since this was a fantasy game. Golden Axe had started that tradition for brawlers many years earlier and Capcom was honoring the tradition. Players could collect magical orbs and summon powerful strikes. Using the orbs resulted in a brilliant background to be displayed, showing off the mystical or elemental gods being called upon. The graphics on the summons were some of the most beautiful pieces of art ever featured in a Capcom title.

Not only did the attacks become more impressive as the game progressed but heroes such as Leo gained a new sword and shield as he leveled up. Imagine how difficult it would have been to show a Street Fighter’s costume getting better gear each time they fought. The amount of memory and programming talent required to do that would have been insane. Warzard would save each player’s progress locally and they would put in a button command so they could continue leveling up each time they started a new game.

The locations of each encounter left audiences wanting more. These were not the typical backgrounds in a fighting game, the middle of a street with random pedestrians, some back alley or the top of a building. They were instead levels that told a story. Some were in wide open plains and others inside mysterious castles. Each civilization on this planet had had a history, they reflected an indigenous culture. The art team at Capcom was sure to present it with rich colors and layers of details.

It wasn’t hard to imagine that Capcom had great plans for the world they had created. The places in Warzard were meant to be revisited. They were the types of locations that the greatest RPG developers had been crafting over the past decade. There was one advantage to them being placed in a fighting game. The fixed perspective meant that the artists had a greater liberty with color, texture and even scale and proportions that would have been difficult to recreate in 3D. The artists could make the stages appear like the pages of a fantasy storybook and not necessarily a real location.

Chief among the background artists was Ikedai, whose design of Darminor looked like a watercolor painting come to live. Ikedai was one of the newer artists at Capcom, as was Sakomizu. The strong contrast of the Sakomizu illustrations, the bright colors and solid ink blacks had been seen earlier in the Strider 2 art. This style was a standout and was featured prominently on much of the official Wizard poster art. All of the senior Capcom artists working on the game would get highlighted in the credits.

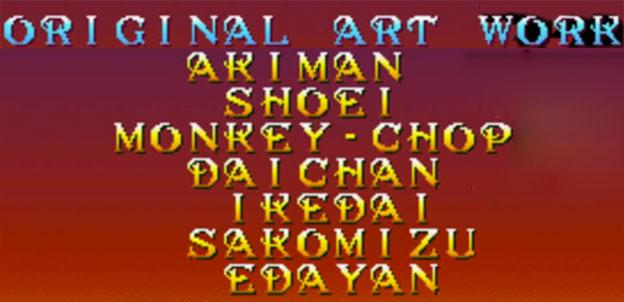

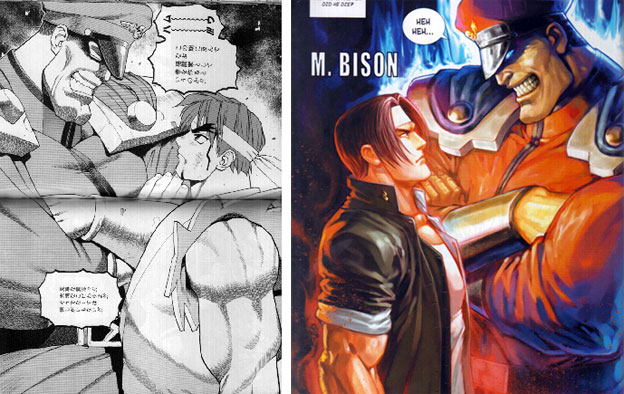

The credits featured a list of seven artists for creating the original art. They were a handful of the most influential designers of all time and were actually listed by seniority within the studio. I sometimes get asked how to tell them apart in my blogs. It is easier if you place a couple of examples side by side, so here’s a short summary for things to look at while studying the drawings. At the top of the Warzard credits were Akiman and Shoei. Their work defined the official, cabinet and sprite art on the CPS-I and CPS-II hits. The paintings of Shoei were done in paint and markers. His best worked was comparable to oil paintings. He captured the personality of the various fighters in Street Fighter canon and were very much the foundation for all the character models in Street Fighter II. Akiman should need no introduction, as a character designer he brought a lot to the table. He had a very strong manga style and created most of the early black and white Street Fighter II designs. His poster work saw much lighter color blends than any other artist on the team. Despite the lightness of his colors the figures still conveyed weight and movement. Of course if you remember one thing it’s that he created Chun-Li.

The third artist credited in Warzard was Bengus aka Gouda Cheese aka CRMK. In this game he was listed as Monkey Chop. His unique style was featured prominently on the development of the Street Fighter Alpha / Zero series and the Vampire / Darkstalker games. His proportions were very exaggerated. Zangief for example was so muscular that he was about as wide as he was tall. Dhalsim on the other hand was very thin and angular, almost alien-like in appearance. His work in these games also went on to influence countless artists and animators, not only in Japan but in the USA. Bengus’ preliminary pencil work might be colored by another Capcom artist or vice versa. His fingerprints were very much in Warzard, specifically in the opening animation and summons. Shoei and Akiman sketched out the concepts for the various monsters in the game, traditional demons and giants in armor, and Bengus went in right after to give them a completely fresh take.

Two of the younger members of the art team, Daichan and Edayan had cut their teeth working on the art for the Street Fighter Zero, Street Fighter EX and Rival Schools titles. The style of Bengus had certainly rubbed off on them, however fans of Capcom should take note at the preferred media that each worked in. Edayan filled his pieces with bold colors, a mix of anime influences and digital techniques were his calling card. He blended reflections and multiple sources of lighting seamlessly on the clothing and skin of his figures. The style of characters were very angular, their muscles were not as exaggerated as those of Bengus, yet not as flowing as those of Akiman. Instead the art was somewhere in between.

Daichan was an accomplished traditional and digital artist. He was great at painting on canvas. He did a number of large panels that were reproduced as arcade posters. His painting of Ryu and Gouki staring at each other from Street Fighter Zero 2 was legendary. It would be revisited in comics and would be copied by manga artists in Japan and China. Daichan and Edayan had art on the cabinet, in the official guide book as well as in the Capcom Secret File (an arcade flyer) for Warzard. Their strong sense of color most likely influenced the color choices on the costumes of the villains and even stages themselves.

The game was simply breathtaking. It was leaps and bounds above Super Street Fighter II. In fact it was far ahead of what the competition was doing. Other studios were fixated on adding more and more characters to their lineup, some of them with many of the same moves of other characters in the series, Capcom went the opposite direction and created a small number of memorable heroes and villains. This was of course in part to the time that it actually took to create higher-resolution sprites and higher-quality sprites as well. From a game play perspective it had a number of unique elements, the ability to save your progress and level up the main characters. Capcom was so certain that the game had a bright future that they even teased what changes were in store for a sequel.

Leo was created by several shaman from a primitive tribe, a lion was chosen to defend them from Valdolll. The transformation into a man was halfway complete in the original game. Leo was meant to become a human and eventually a king to his people. Once peace had returned to the land Leo was turned back into a lion. It was a bittersweet ending for the character. The “true” version of Leo was teased, along with evolved versions of all the other characters. The armor of Kenji had changed slightly and looked more beetle-like. Tabasa had a double-horn hat and Tao had gained some more costume details that appeared pulled from the Chinese opera. What sorts of new moves would they have added? I doubt that Capcom would have simply brought back the same villains in a sequel. It wouldn't have made any sense if they did. Given the development time and cost to produce Warzard it stood to reason that Capcom had to kill the sequel. With Street Fighter III they could keep adding new characters, they could add new stages and new upgrades and keep existing characters around as well. Warzard would have to be redesigned with every sequel. It was not practical from a development standpoint however the bold experiment was something that the fighting game genre sorely needed. Warzard was a perfect example of using a fantasy theme within a fighting game. Neither Eastern nor Western in setting it built universally recognized heroes and villains. Do you think that this game deserves another chance? If so I'd like to hear about it. As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment