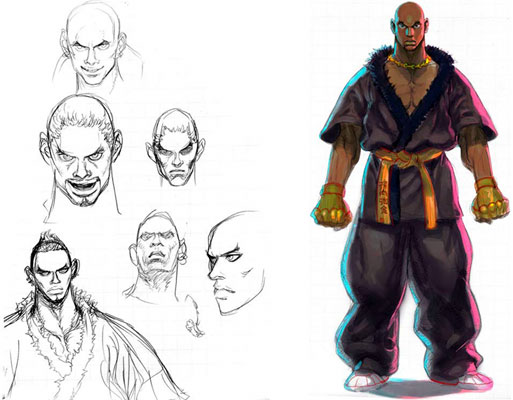

Street Fighter IV was released in 2008, it was 11 years after Street Fighter III had come out and a generation removed from the stereotypical fighters from 1994. A gamer might assume that in that span of time Japan had become more familiar with the various ethnicities that made up the USA. After all the internet had only served to make the world seem smaller by making trends move faster. That seemed to be the case at Capcom. During the early stages of character development a new fighter named King Cobra was created. The character looked interesting as he was a mash up of Hip Hop culture and traditional karate. He had a shaved head and sported and earring, his gi had a fur lined collar. The character looked very similar to Meera, a character from the manga Tokyo Tribe by Santa Inoue, Mr. Inoue had done an exceptional job of bringing Hip Hop culture, the language, music and fashion to his native Japan. He had followed it for as long as he could remember, which was interesting considering that the Japanese had been deemed an insular society by the rest of the world.

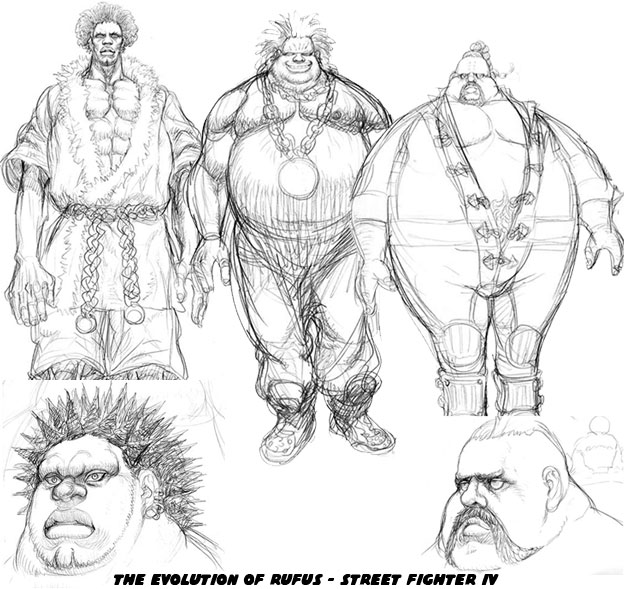

The designers at Capcom did not have to travel far to learn what made a black culture interesting and how to bring that into contemporary character design. Tokyo Tribe had done all the work and acted as a primer for urban trends. Readers could find out about mix tapes, graffiti, criminal organizations and thug life. Plus they could see how strongly it contrasted against the Japanese landscape but was acceptable as a youth movement. Meera was actually a villain in the series which made the points of reference all the more unique. King Cobra wasn't always a young karateka. In his earliest concept art he was actually a giant. He was designed to be a rival of Ken. The studio wanted Ken to have his own Sagat, or impossibly big obstacle.

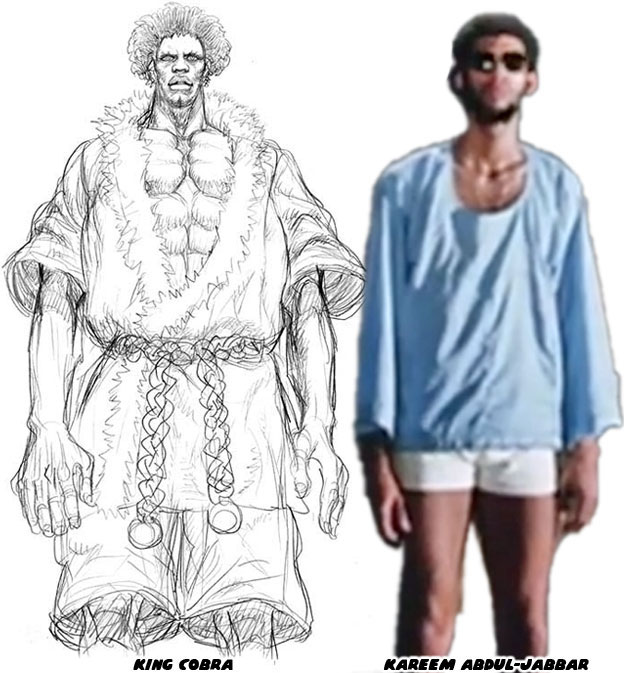

Before the Meera look King Cobra was tall and lanky with a big afro. The design was taken from Kareem Abdul Jabar, a villain from the Bruce Lee film Game of Death. Street Fighter IV designer Daigo Ikeno thought that the point of reference was a bit dated. Although martial arts film fans considered the piece timeless the character was not. Jabar was barefoot, sported tiny shorts and a long sleeve shirt. He looked a little silly by the standards of today. There didn't seem to be a strong unifying costume for the Jabar as there were for the other fighters that Lee had faced in the picture. Jabar was actually vacationing in Hong Kong when he decided to visit his friend and martial arts teacher. Lee took the opportunity to cast him in a role. The costume shop didn't have anything ready for the 7' 2" NBA center so he just wore whatever he had handy. This would explain the leisurely clothes.

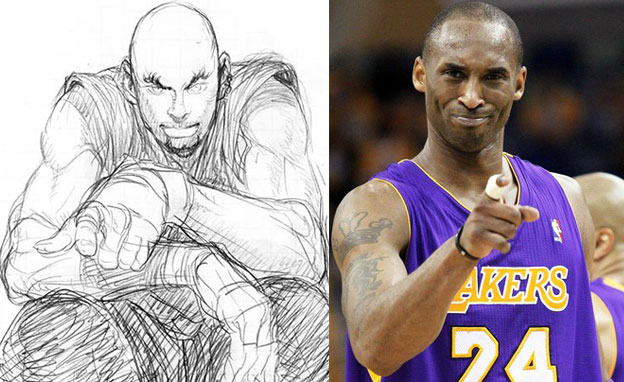

The original design of King Cobra / the Black Cobra gave away that the character was from the '70s, it was a step back to Mr. Jones territory. Ikeno was looking for a younger face and a more contemporary cultural touchstone. The Hip Hop elements seemed obvious. The character would be a young upstart looking to dethrone Ken. He would be equal parts attitude and ability with an homage to the Karate Kid (the original one, not the remake) thrown in for good measure. Ikeno wanted Cobra to be appealing to new players yet also threatening to the older guard. Abdul Jabar needed to be replaced as the template and even Shaquille O'Neal had become dated. Kobe Bryant became the most obvious choice. He was tall but not gigantic. He was slender but still very athletic. The face, the earring, the charisma and confidence of the young Cobra were very reminiscent of the Black Mamba, the nickname that Bryant gave himself.

Cobra represented just a hint of Hip Hop culture, truly an artistic global culture and not limited by USA ideals. It was just enough to remind audiences that he was the modern urban youth, not a jet-set playboy like Ken, nor a wandering solemn hermit like Ryu. The gold chain on his neck was not too bold or thick, he could never be confused for the Blacker Baron or Joe Fendi. He did not sport any sort of earrings, medallion or emblem that would have dated his appearance. His jewelry was very clean and simple. The ruffled edge of his gi gave him personality. The sneakers were classic, something that would have worked in any decade of the modern era. They were appropriate for the look that this character represented, a cue from the traditional and modern, not unlike the wrestling boots that contrasted the dress of Chun-Li. The sneakers were something that could be worn while traveling down city blocks walking into dojos and beating people up. The legend of the barefoot master did not make much sense in the modern city. Cobra was young and bold and not scared to bring just a little bit of his world into the Street Fighter universe. His design was not so bold as to try to change the universe and our attitudes towards the established characters. His belt and uniform reminded us that he was mindful and respectful of the martial arts.

King Cobra had a different statement on his belt, Jyakuniku kyoushoku wich roughly translated to "survival of the fittest / law of the jungle." These things combined with the gold and black and cobra logo on the back of his gi made him a subtle homage to the Karate Kid villain Johnny Lawrance. It was yet an additional layer of detail that Ikeno laid down that would have gone over well with audiences. Certainly this was a design for a strong black fighter that would have been very appealing to Americans. It was much better presented and respectful of the fighting arts than Dee Jay or the basketball players mentioned in the previous blog. King Cobra followed the traditions of the classic characters yet visually did not have to bring up racial prejudices or gimmicks to make him stand out.

The connotation of all blacks being good dancers was a stereotype as old as the Sambo himself. One of the oldest ideas about blacks was very dehumanizing. According the slave owners the blacks were born with natural rhythm and an ability to dance. They insisted that the savages had no concept of self and that they "would even dance on the auction block." The decedents of the slaves were some of the early successful entertainers in turn-of-the-century America. Unfortunately many of them were paid to perform as minstrels. They had to act like clowns in black face makeup and be the ugly parodies of themselves that the racially charged audiences expected to see. They sang and danced on stage and in film so they could afford a better life. Unfortunately no matter how rich or famous they got they were still second-class citizens. They could not eat where they wanted, travel where they wanted or even consort with non-blacks without fear of reprisal by racist groups. African-Americans had therefore been very critical about their portrayal as dancers and entertainers rather than people first and foremost for most of the 20th century.

From the early black and white pictures to the first audio and full-color feature there had always been an African-American pioneer working in film. It took a long time for Hollywood and the rest of the world to appreciate the contributions of blacks not only in entertainment but in "American" culture. If someone made the mistake of assuming that they were natural at it they could be corrected. Blacks worked hard for everything they had become famous for, they put up with tremendous amounts of hate and bigotry while claiming a slice of the "American Dream." The lessons from history were obvious. If minorities wanted to be taken seriously in the arts or entertainment then they had to work hard for it. If they wanted to see minority characters in gaming then they had to become programmers, designers and developers as well. A generation would grow old waiting for the publishers to catch up.

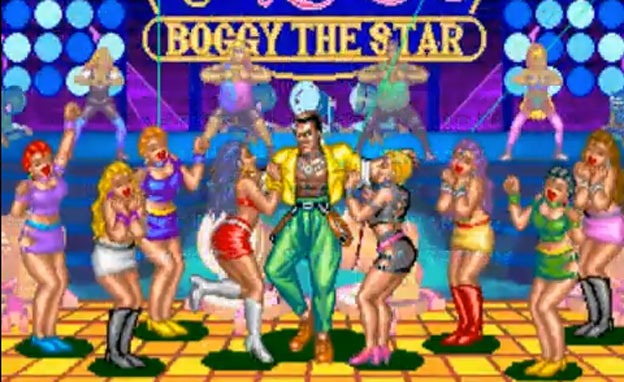

Whether King Cobra was the Black Mamba in disguise, a positive role model like Dudely or a throw-away character like Boggy would never be known. The Japanese were merely reflecting US pop culture. They did not have the complete picture of black society in the USA. However not every developer relied on stereotypes while creating a lineup. Not every developer believed in the images that they had been fed by the media. Many travelled the world, did their homework and learned that different ethnic groups were much more interesting than any news clip or music video. When these designers went back to the drawing board they developed characters that were much more universally appealing. They accomplished this by incorporating actual cultural cues and details into their black figures. There were reasons why the genre survived the rise of the home consoles through the '80s and the arcade crash of the late '90s. Truly great fighting games had a diverse fan base made up of every ethnicity and background. When these players saw a diverse cast, one that they could identify with, they were willing to embrace the series. The audience would continue to support the publishers as long as they continued developing great games with a broad well-respected cast.

When the developers in Japan and the US took the time to incorporate real elements from history and society into their titles they accomplished something profound. They managed to expose the world to systems and cultures they might have previously never known about. The fighting genre was indeed very influential to a generation, but not in the ways that the politicians had made it out to be. It did not turn fans of Street fighter and Mortal Kombat into cold-blooded killers. It did however color the perception of young impressionable gamers by making them aware of how amazing the world really was. The next blog will explore the ways that one of the darkest times in modern history also changed a beautiful art form. As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment