Namco showed that they were a major player in the arcade industry with the success of Galaxian in 1979 and its follow-up Galaga in 1981. The games were so successful that they helped their US distributor Midway grow by leaps and bounds as well. The success of the Pac-Man, Ridge Racer, Tekken and Ace Combat titles helped cement Namco's position as leaders in entertainment. The space shooters from the company had always done well historically. Each game was an innovator for the genre, whether it introduced a scrolling background, added a bonus stage or chaned formats from sprites to 3D polygons.

Namco was willing to experiment with their formula in order to keep the experience fresh but most important to keep audiences engaged. Something that won over fans was consistency with the genre. The most celebrated titles had a familiar feel to them. The fingerprints of the developers were all over the games even when they were in a completely new genre. Why was this? Because the development teams kept copious notes on each and every game they had created. This was nothing new to the industry. The teams working behind every great series could fill volumes with concept designs, notes, background, programming lessons and even blueprints. What separated Namco from their contemporaries however was something more obsessive.

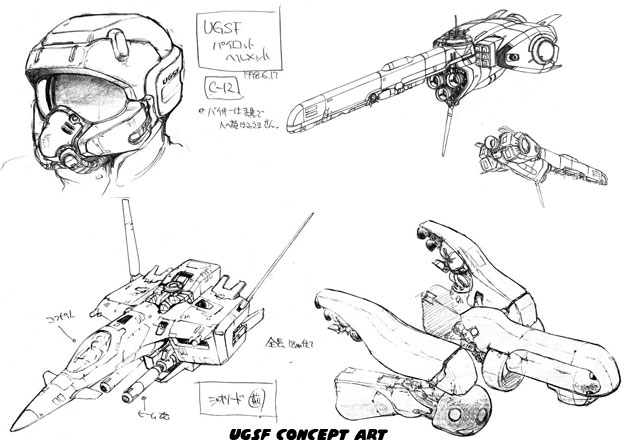

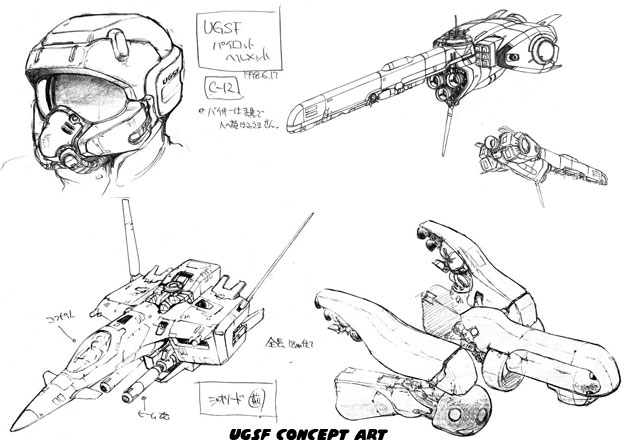

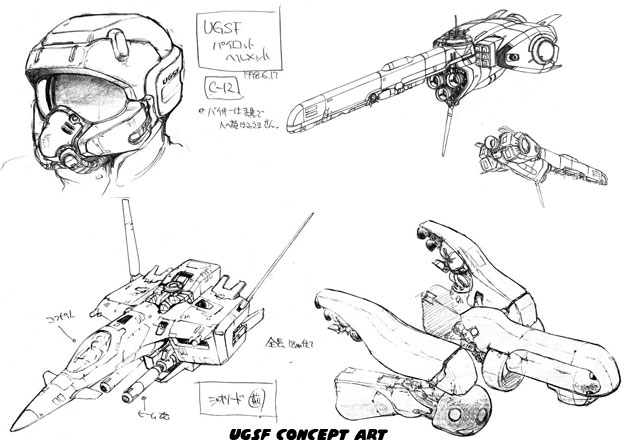

The designers would lose sleep over details never seen by audiences. In order to build a better game the developers had to become intimate with the fictional world they were creating. In the case of the space shooters it would be fleshing out the canon of the UGSF (United Galaxy Space Force). Absolutely no detail was overlooked. The signage on the spaceships, both good and bad had to be planned out. The colors, framework and layout of ships were cataloged. Bases, planets, weapons and technology all had to be meticulously detailed. Even though the company had no plans to create a game where the pilots inside the ships were ever seen the designers still kept notes on them. The layout of the cockpit, seats, displays, the shape of the helmets, the cut of UGSF uniforms for both officer and soldier ranks, what the space suits looked like, if they were strapped with a weapon and even how their rank would be displayed had to be considered. Certainly many modern AAA studios could show how their teams of artists did the same thing during the development of a modern blockbuster. Of the current studios none would have allowed their designers the leeway to focus on things that would not appear in any way shape or form in the finished game.

The insanely detailed notes and volumes of concept art became shared knowledge in the offices of Namco. In many cases these things decorated the walls of the offices. It wasn't an employee working here or there that seemed to know the particulars of the science fiction world Namco was developing it was the collective that knew about it. They all contributed to the development of the UGSF canon over the years. The studio did not seem to forget even the tiniest little detail either. For example, when people think of the ship featured in Galaga they might imagine a tiny white space jet that could be joined at the wing to another. If the fans were asked to draw it from memory they might even be able to sketch out a design that resembled the blocky ship from the arcade hit. Yet the people at Namco had a lot more in mind than audiences could have ever imagined. First off it had a name and class. The star of the game was the Coleoptera Fighter. In other Namco games the ships would become much larger, more defensive and carry different names. The fighters appearing in many of the early Namco hits were limited by the capabilities of the graphics engines and not by the imagination of the developers.

The artists wanted to present a spaceship that would hold up to the greatest designs from film and animé. Fans could identify T.I.E. fighters and X-Wings with just a few pixels, unfortunately for Namco they had to rely on the imagination of gamers to fill in the details missing for their own craft. Something similar could be said of the gameplay of those early UGSF hits. The designers had epic space battles in mind while planning out the adventures. They had grow up on a steady diet of amazing shows and animation, including Captain Harlock, Space Battleship Yamato and Star Wars. They wanted to capture the action featured in those titles but allow the audiences to become the heroes of the story. Of course it was tough to include any sort of story with the limitations of the early arcade hardware. With barely any memory, a few tones from the sound board and a limited color palette the developers at Namco had to focus on making a fun game first and foremost. They would have to pack away their ambitious goals until technology had caught up with their imagination. The people working on the space shooters were not alone with these struggles.

Other groups within Namco worked on different genres. One in particular worked on maze games for the studio. Mappy and Pac-Man had done very well in the genre. Yet even those designers had to explore the boundaries of what was possible. They introduced elements of science fiction into the format. The first of these new experiences was Dig Dug. The hit from 1982 made little to no sense to the western gamer. Try to describe the game to someone, especially a non-gamer. There was a little blue man that would dig tunnels with a jackhammer and then shoot at dragons and orange masked balls with an air hose. He would then inflate them until they exploded and that's how you earned points. It sounded like a bad acid trip rather than a video game. Thirty years later it still did not make any sense. Not that it mattered though because gamers in the west and east could not get enough of the experience. It was a challenging maze game that introduced all sorts of new elements and enemy types. It also created some memorable mascots along the way. Baraduke raised the bar on space exploration. The title from 1986 wasn't a puzzle game but actually allowed the main character to travel through an alien outpost instead, running, flying and shooting everything along the way. The hero of this game was actually a female, a UGSF soldier named Masuyo "Kissy" Toby. It was a fantastic concept that had predated heroines like Samus from the Metroid series. While the mascots featured in those games were blocky little characters the designers always kept in mind some more realistic representations of them for future use.

It was about this time in the '80s that Namco began working in earnest to shape the UGSF continuity. The designers began looking back on their catalog of games and began finding relationships between the various titles. The company decided that Masuyo was actually the estranged wife of Dig Dug himself, a fellow that went by the name of Taizo Hori. The name Taizo Hori was actually a play on words, in Japanese his name sounded like "I like to dig." The two characters had kids which would appear in games that followed many years later. Susumu Hori, Ataru Hori and Taiyo Toby came into their own in a series called Mr. Driller and Star Trigon at the end of the '90s and start of the new millennium respectively. The reasons why Hori and Toby were separated were never revealed by Namco. Some artists speculated

why they were an estranged couple but nothing definitive was ever posted.

It would not be the first time that mature themes were explored in science fiction. The origins for Baraduke were rooted in the film Alien. The movie was one of the first to combine horror and science fiction equally well. The film starred Sigourney Weaver as a space explorer named Ellen Ripley. In it her team of miners came across an extinct alien settlement. When one of them became infected with an alien parasite it quickly turned into a life or death struggle for the entire crew. The entire tone of the film was handled very seriously. There was nothing remotely fantastic about the content as was the case with Star Wars, instead the story played out as an earnest drama should. Violence and gore aside it certainly was not meant for children. The 1979 movie forever changed the landscape of cinema and became a cultural touchstone for what space exploration could become.

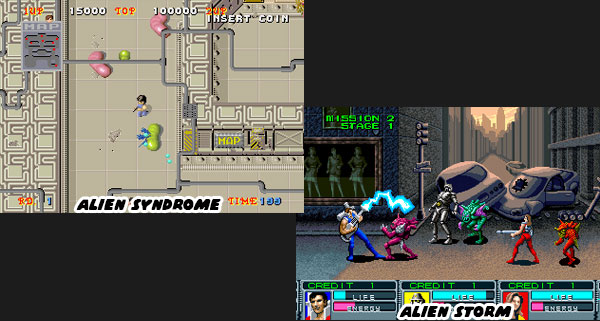

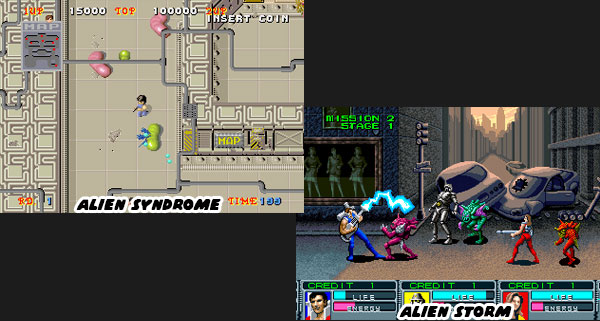

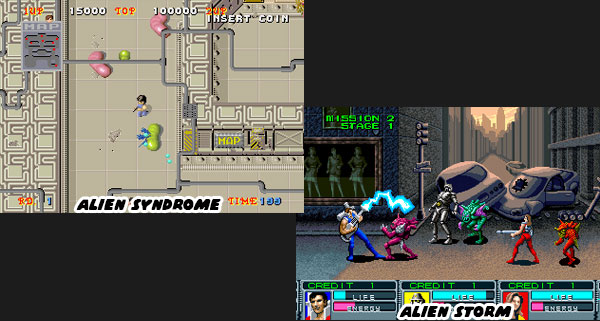

Alien had influenced the designers at several Japanese studios when it debuted. Sega's Alien Syndrome from 1987 and Alien Storm from 1990 were two completely different takes on the genre, one was serious and one was very over-the-top but both had hints of the classic film in it as well. The 1986 hit Metroid for the original Nintendo Entertainment System was also influenced by the film. Through all of the changes in science fiction and gaming over the past 40 years Namco would stay focused on their own continuity, They kept grinding away at the UGSF universe and never lost track of what could become. When the industry began to change its operations to focus on 3D engines Namco was already ahead of the curve. Many of the developers working at the studio had a good idea as to what the next great hits from the company would be.

The advancement of 3D graphics in the arcade and on home consoles turned out to be the biggest gain in company history. The programmers and animators could finally put on screen what they had spent an entire generation only dreaming of. Even the iconic battles in Galaga became more mesmerizing when visualized as actual 3D engagements. Solvalou, Galaxian

3 and Starblade were the first chapters in a run that no other studio would be able to match. The next blog will look at the nexus of the UGSF at home. I’d like to hear about it in the comments section. As always if you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment