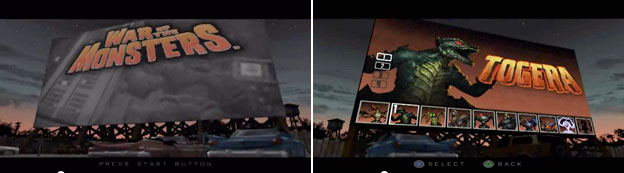

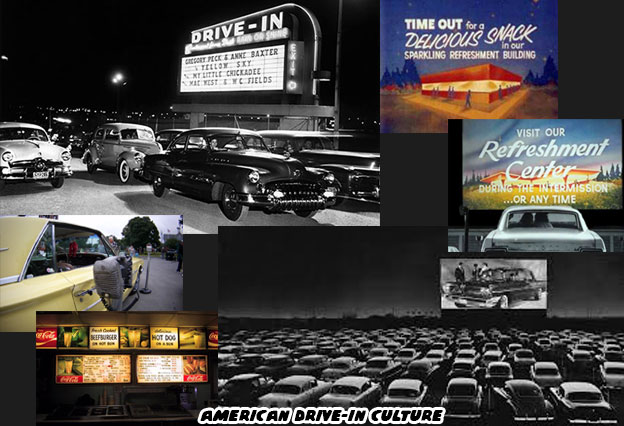

War of the Monsters (WOTM) was more than just about the nostalgia of the classic drive in movies. It actually had tremendous game play. The experience was a free-roaming 3D fighting game akin to Capcom's arcade gem Power Stone. Most fighting games and most brawlers were strictly 2D affairs, even the crown prince of the genre, Rampage, was a 2D experience. In War of the Monsters players could move their monsters in all three dimensions. They could run, leap and even climb buildings. Some creatures could even fly.

Incog Inc. actually did a good job of giving each creature a specific sense of weight and mass. The insect character Preytor was a giant praying mantis. She moved and turned quickly, was light on her feet and could scale buildings with her six legs much faster than Agamo the living stone idol. Agamo was a huge lumbering force whose footsteps echoed with the sound of a rockslide and whose punches could deliver far more damage than Preytor's claws. There was a trade-off for speed versus power on every character. The speed and movement of the characters actually made sense in War of the Monsters. Their physical makeup, whether it was flesh, stone or metal complimented the creatures. Incog developed subtle differences in the way each monster moved and handled based on their structure. They controlled with a sense of momentum especially when running or jumping. Players could not accelerate quickly or stop on a dime with the biggest brutes. When an explosion went off they slammed into buildings and flipped end-over-end in a realistic fashion. They were not at all rag dolls. None of the Godzilla fighting games gave audiences even a remote sense of mass or momentum. The WOTM cast also had their own original sounds, taunts and roars, none were alike.

Speaking of sounds, the music featured in the game was orchestrated by Big Idea Music Productions, out of Colorado. The studio had worked with Incog on titles like Warhawk, God of War and Twisted Metal. This was by far the best soundtrack they had ever produced and one which I would easily rank in the top 10 best game soundtracks ever. Each level actually had two different soundtracks in the queue. There was a main level theme and a battle theme. The two themes complimented each other and could be effected by the players. If a player were far from the opponent then the level theme played, as they got close to the opponent then the game would mix in the battle version. The instrumentation utilizing a full orchestra helped give the score a robust movie quality. Each theme helped heighten the tension as monsters battled inside an active volcano, aboard a space ship or even on the steps of the Capitol Building in Washington DC.

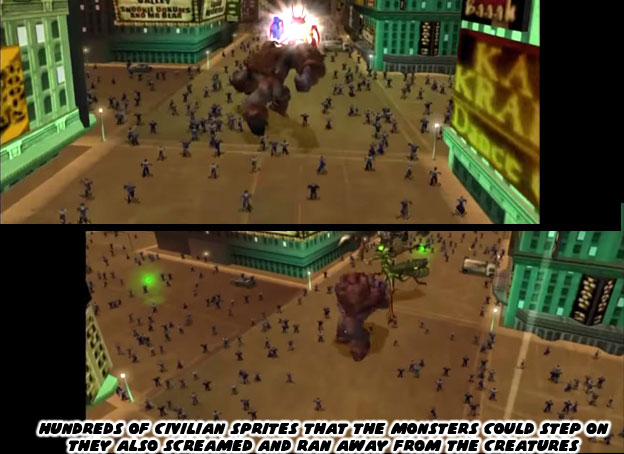

There were eight characters for players to choose from and two additional ones that could be unlocked, each of which moved uniquely and had their own advantages and disadvantages. Incog found a perfect balance between the size of the characters and the scale of the environments. The monsters were about 75 feet tall, about twice the size of the Rampage monsters yet only about a quarter as tall as the King of the Monsters cast. This translated into many different elements. Since the monsters were bigger than the Rampage cast then they could more easily destroy the environment. But they weren't so tall that they were bigger than the tallest skyscrapers, and unable to climb them, like the King of the Monsters crew. Plus the scale that the monster were presented at translated into surprisingly tiny details that could still be made out by audiences. The amount of detail placed on the drive in theater at the start of the game was nothing compared to the details crammed into each level.

Buildings in each city had distinct architecture, there were ads, marquees and billboards that did not seem to be repeated on other levels. Cyclone fences on military bases had warning signs that could be read. Searchlights swept the corners of those same dark military compounds. Parking lots were filled with different types of cars. The studio went so far as to paint in the lines in the lots and even have tiny oil / transmission fluid stains in the spots. Parks had winding footpaths and tiny benches. Bigger cities had moving traffic, circling helicopters, rolling tanks, turning construction cranes and functioning missile launchers. Even the cabana, multi colored deck chairs and patio umbrellas at an island resort pool could be seen by sharp-eyed players. Vehicle types were also very distinct. Police cars, delivery trucks, tour buses, fire engines and sedans were on the roads. This attention to detail wasn't limited to just the cars. Yachts, sailboats, cruise ships, fishing boats and catamarans were set afloat, or docked on various stages as well.

Players could make out the waves that came in on the beachfront levels. If the monsters fought in the water they would send up enormous splashes. If the monsters ran through the water they would even kick up "rooster tails" of spray. Consider the amount of detail that SNK placed on the King of the Monsters years earlier. Those isometric details now had to be three-dimensional and look as good from every angle. Incog delivered on that challenge tremendously. Pedestrians could be seen screaming and running for their lives. The animated sprites were barely a few pixels in height but responded realistically to the monsters. They would scream en masse and fan out and away from opponents.

Creatures could actually walk through the crowds and flatten a few people with each footstep. Tiny red splatters were all that remained for those caught in the path of destruction. The sound of pedestrians screaming in terror would increase as the monsters approached. If there was a police car nearby the sirens would get louder or softer depending on which way they were moving on the streets. Traffic actually moved through the tiny streets and tried to maintain the right of way. Cars would even swerve around other vehicles or debris! News helicopters flew above the action while military assault choppers followed opponents around buildings and fired powerful rounds into them. Audiences could climb buildings, jump from rooftop to rooftop and snatch the helicopters out of the sky. Some levels even had UFO ships that shot green plasma blasts. They hovered and zipped from spot to spot, faster than any helicopter.

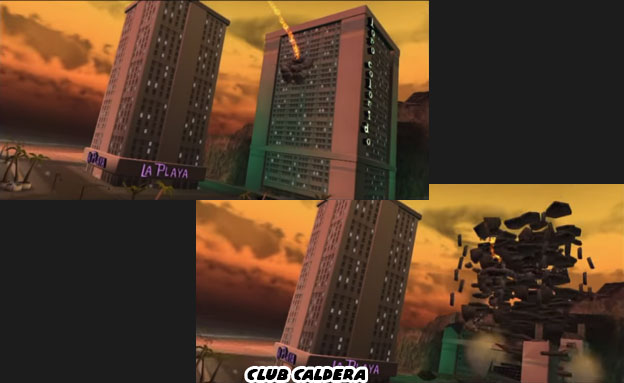

The environments were completely destructible. Buildings could be toppled, imploded or disintegrated. An entire city could be flattened to the ground. Players could use rubble, air conditioners, generators, dumpsters, cars and radio spires as makeshift weapons. If a player grabbed an energy transformer then they could send an electrical shock to opponents or throw it for a spark-filled explosion. If a player grabbed a rocket-firing tank then they could unload a salvo at opponents as if it were a massive handgun. Players could jump into the air and smash aircraft or UFOs using only their mass. Some of the taller buildings could collapse and crush opponents and players as they fell on them. Savvy players could lure an opponent to the right spot and earn a quick victory with a falling skyscraper. Several levels had hidden features that could be triggered if the right conditions were met.

Baytown, a city modeled after San Francisco, could have an earthquake that completely changed the shape of the environment if one player caused enough damage to the city. If players threw an object at an alien ship off the coast of Tsunopolis then it would shoot a powerful beam at the ocean. A tidal wave would then crash through the Japanese island sweeping all the pedestrians right off the map. The levels themselves were bordered by the same pulse emitters featured in the introduction movie. These emitters put up translucent walls that contained the destruction to a certain area. Apparently the government thought the collateral damage was acceptable. It was actually a good supporting detail. Incog did not simply focus their resources on the playable level and just blur out what was outside the borders. Gamers could see that that the world extended beyond the barrier. A major town, like Metro City did not end where the pulse emitters were. Players could clearly see roads and buildings behind the emitters, there was even a zeppelin floating just above the outskirts. This detail helped maintain the immersion on the arena while reminding audiences that the game universe was indeed fleshed out, waiting to be explored.

The combat system was the most robust aspect of the game. It was meant to be a brawling game after all. All of the attacks could be triggered by pressing two buttons for either weak or strong attacks. Monsters had a diverse set of combos that could used by learning the right sequence of button presses. Players could alternate button presses and create unique combination strings. Players could even break attacks, push opponents back, steal a weapon and even slip out of grapples if they caught the timing of an opponent. This came in handy as many of the monsters were relentless in battle, even on the easy setting. The computer AI was dialed in to be just about as brutal and cheap as it could, especially when it was two or more computer controlled monsters against the player. Those that have played through David Jaffe titles could testify that there was a level in God of War or Twisted Metal that felt particularly difficult, especially when it was one against multiple opponents. In War of the Monsters if an opponent were greatly weakened then they might run away and look for a major health upgrade. It could be maddening when players were trying to fend off two monsters at once. Audiences learned to be just as brutal as the computer if they hoped to survive. Gamers had to use every weapon at their disposal and even resort to some cheap tactics while dealing with multiple creatures.

The characters had a secret ability of sorts. If a player pressed the Select button their character would perform a taunt move. If players had two full bars of attack energy then that meter would flash rapidly. If a player taunted during a flashing meter then their character would get glowing fists and do about 25% more damage per hit. The attack meter drained steadily once players had activated it and would stop once the meter had drained down to a single bar. Players could keep recharging the energy by looking out for power orbs. This unique gameplay mechanic was revisited in the God of War series under the "Rage of the Gods / Titans / Sparta" mode for Kratos. It could certainly help to turn the tide of battle when dealing with multiple opponents.

Each monster had a close and ranged special attack. The close one was good for clearing away groups of monsters that were swarming around players. The ranged attack could drop opponents making a run for a health upgrade. Some characters had hidden uses for their super attacks. Gas tanker trucks were the most destructive thing that players could throw at each other. In addition to the damage caused by the explosion the tanks would coat the monsters in gasoline and slowly burn away their health. The problem was that they were not always accurate over long distances. The Japanese robot Ultra-V had a ranged super attack where its arm would shoot out like a rocket to stun and reel in an opponent. That attack rarely missed even if launched from the opposite side of a level. If Ultra-V were holding a gas tanker when doing the special attack then it would shoot out the arm and punch the opponent with a powerful explosion. The game was filled with all sorts of amazing hidden uses for regular and super attacks. Special attacks and even regular attacks tired out the monsters. They could regenerate their attack stamina slowly if they waited or quickly if they destroyed the environment. Incog turned the destruction element from the films into an important game play feature. Characters could also recover health by searching out green radioactive markers.

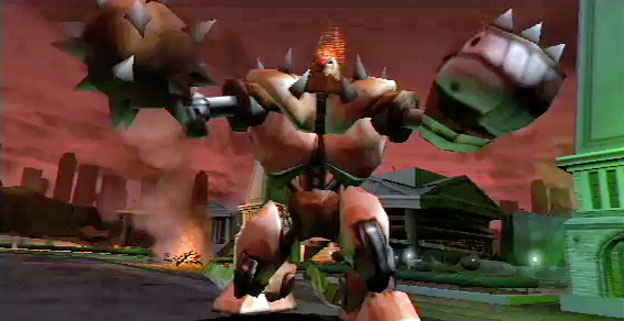

Players needed to learn all of the moves at their disposal too because they also had to contend with boss characters. There were three major bosses in the game. Each was designed to make all of the playable characters seem less imposing. The bosses required a particular strategy to defeat and none could really be fought hand to hand. The robot Goliath Prime, from the secretive military Area 51, towered over the other characters and could throw them around like rag dolls. It could also transform into a spinning wrecking ball as well as a two fisted artillery cannon. Then there was Vegon, the three-headed plant monster born from the center of a nuclear power plant. Vegon was actually the largest monster in the game and capable of swallowing the regular characters whole. The final boss was Cerebulon, the destroyer of worlds. That boss had three unique transformations, each one was memorable and all requiring a specific strategy to defeat. The effects, voices and game play built around the bosses was amazing. They really had to be played against to be believed.

As much praise as I've heaped on WotM the game did not really earn high scores from every publication or site. If I could find a major failing with the game it was without a doubt the camera system. The camera was very loose and turned quickly if the player used the analog controls. Trying the move, aim and throw a weapon was all but impossible by how quickly the screen spun. The opposite analog control did not control the camera but instead the elevation of a thrown object. It was difficult to get a sense as to how far opponents were while running around a level. The good thing was that once a player got close to an opponent the game would auto-lock the monsters. This way a player could trade punches and experiment with different combinations. A player could actually lock onto an opponent by holding the shoulder buttons (L1+R1). This made the experience of targeting an opponent for ranged attacks much easier. This was essentially the fix to the camera system and made the experience much greater. The downside was the the camera lock required players to manually hold the buttons while playing. In order to truly get the most out of the experience Incog should have included the ability to target-lock and switch between opponents. This was a minor detail that completely changed the game play. For the most part it was a minor inconvenience on an otherwise great game.

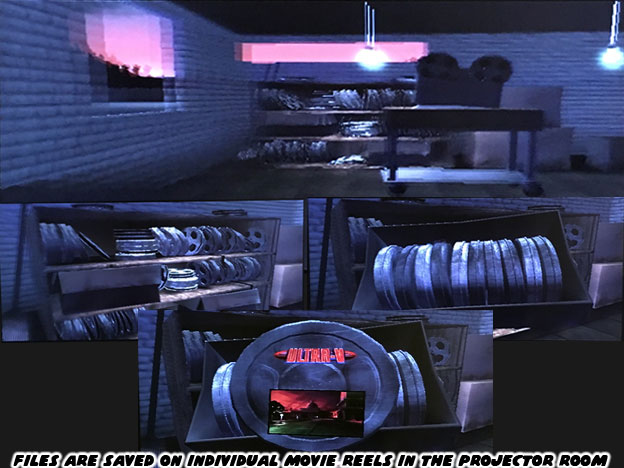

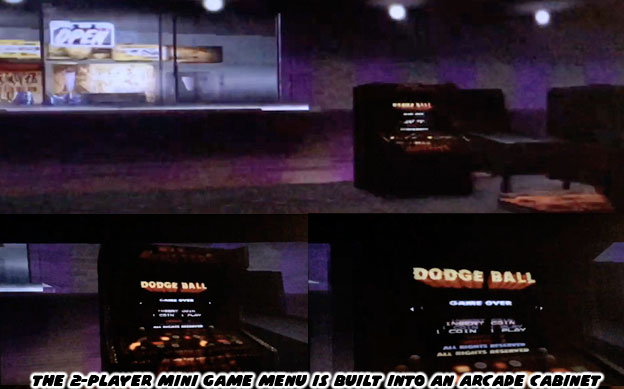

The reward for players that completed the Story Mode was a film that showed the origin of their chosen creature. Players were inspired to begin a new adventure and unlock all the endings and costumes. Those with friends and siblings could battle it out on any level featured in the game as well as a few additional bonus stages. The weakest element in the game were the two-player mini games. They seemed to be added as an afterthought and lacked any sort of polish. Not that it mattered because the actual game itself was rock-solid. Those that got used to the combat system and camera learned to cut loose and enjoy the ride. Incog Inc. had released the greatest giant monster game to date. Although the experience was short, logging in at 11 stages, it had tremendous replay value. The levels themselves were so amazing that players could easily get lost in the details and spend untold hours exploring every street and alley. It was much better to have a handful of unique levels than a hundred cookie-cutter levels, as Rampage had demonstrated.

Mind you, I managed to talk about the game over two blogs and not once did I mention that Mecha Sweet Tooth from the Twisted Metal series was a playable character!

War of the Monsters was the perfect giant monster video game. The individual elements and collective should be studied by all budding game designers. It was exactly the type of experience that players had been missing out on for years. The game was the first to capture the feel of controlling enormous beasts in full 3D without sacrificing design, game play or originality. Players no longer had to use their imagination to fill in the gaps between being a passive participant in a movie theater to being the star of the feature. It was a fully realized vision of what Epyx's Movie Monster had promised way back in 1986. It was also more than what was offered in Giants: Citizen Kabuto, Rampage, Doshin or even King of the Monsters. Players could fight with reckless abandon, plow through buildings, hurtle ocean liners at each other and embrace the primal forces their ancestors once ran from. The cast, stages and even music even were all unique. This game was worthy of joining the established Sony franchises.

Word of mouth helped War of the Monsters build a following. The more players that tried the game the bigger the legend became. Many wondered why Sony hadn't insisted on a sequel. Unfortunately the game didn't sell quickly when it first came out. This was despite a big ad campaign and positive review scores. Sony didn't bother to follow up and push for a sequel. Instead they were focused on David Jaffe's next title, a game called God of War. Many of the lessons that the studio learned during the development of War of the Monsters (and the mountain bike racing game Downhill Domination) were applied to God of War. The lighting and coloring, powerful thematic elements, strong music, sharp graphics and particle effects were rooted in War of the Monsters. Not to mention the Titan levels and final battle against Ares were heavily influenced by WOTM as well.

Fans never forgot about War of the Monsters. When Sony decided to publish it on the Playstation Network on July 31, 2012, the web forums lit up with the good news. The studio that helped optimize the game and sharpen the graphics was Lightbox Interactive, it was founded by former Incog Inc employees. The re-release was well received by seasoned players and a new generation of gamers. Hopefully Sony might consider giving this title yet a chance for a sequel. After all, you can't keep a good monster down for long! The next blog is actually dedicated to the tabletop games. Find out what the genre did for traditional board games and more advanced tabletop systems as well.