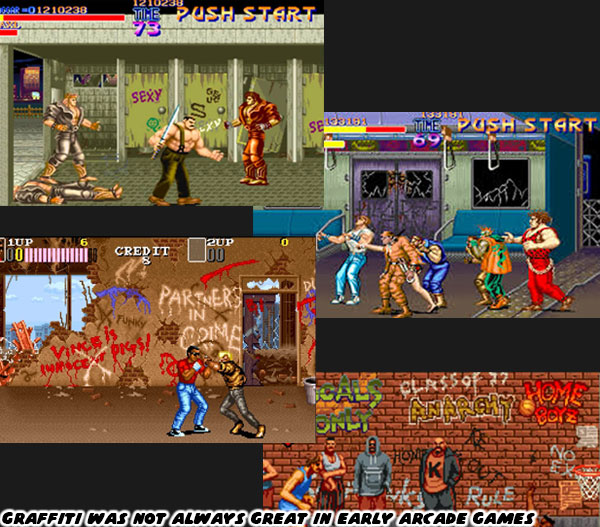

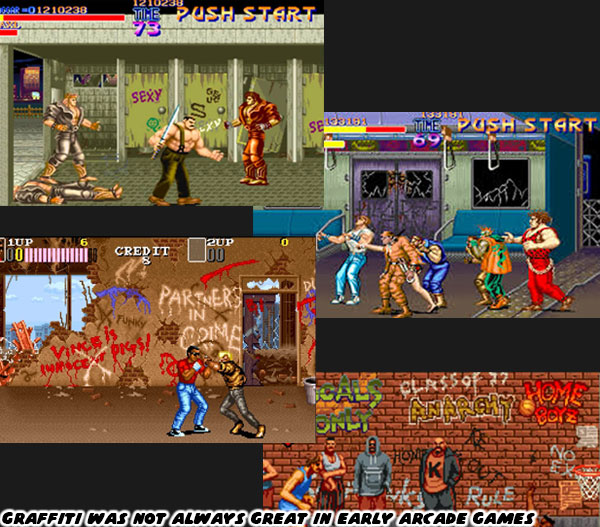

Many Japanese studios set their games in the west, particularly in major cities like New York. No genre had featured this more than the brawlers. The loudest, most colorful gangs would take on all sorts of tough guys on the most dangerous streets on the planet. I had mentioned in the previous blog that the designs for these worlds were pulled from cult Hollywood films. Some of my absolute favorite games were developed by Capcom’s perennial rival Konami. The two studios essentially took the genre over after Tatio’s Double Dragon II: The Revenge failed to recreate the success of the previous game. Final Fight of course was everything that Double Dragon II failed to be. The only title that

I would even argue topped some things in Final Fight was Vendetta. Konami’s previous game Crime Wave was sorely lacking by comparison.

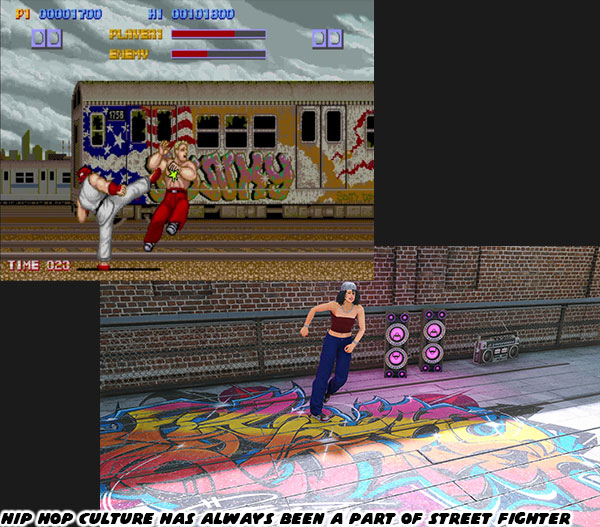

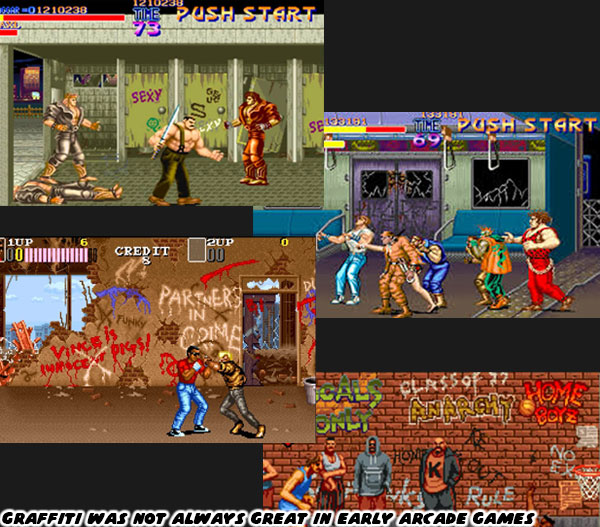

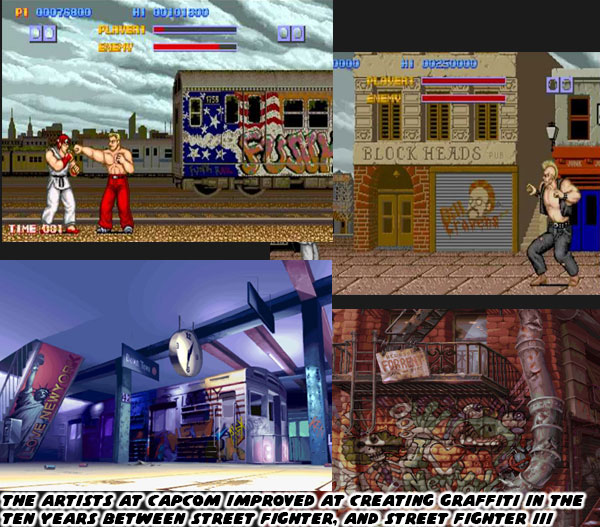

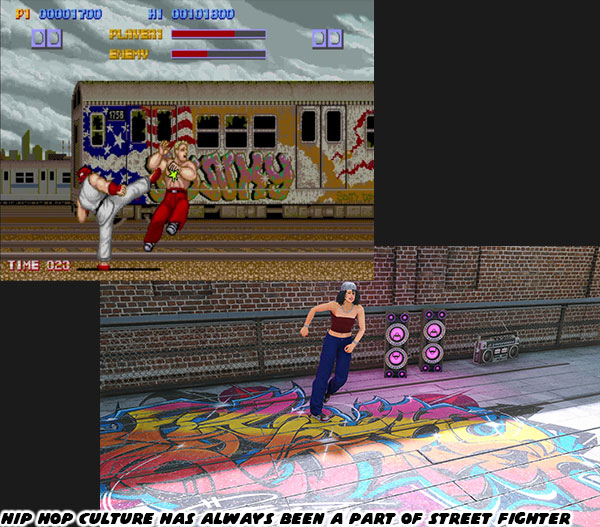

The thing that all of the Japanese studios would do in order to create the look, and feel of the west was the use of graffiti. It instantly transported arcade visitors into the world that the designers were creating. This extended beyond brawlers, it included fighting games, sports games, action shooters, and adventure games. Graffiti in pop culture was a sort of shorthand for gang territory, for dangerous neighborhoods. The thing was that if you had grown up in a big city, if you were familiar with actual graffiti art, with actual gang neighborhoods you would notice how amateur the graffiti was in gaming. It actually looked convincing, so long as you didn’t take too close of a look at the art. Capcom was aware of how to use graffiti going back to the original Street Fighter.

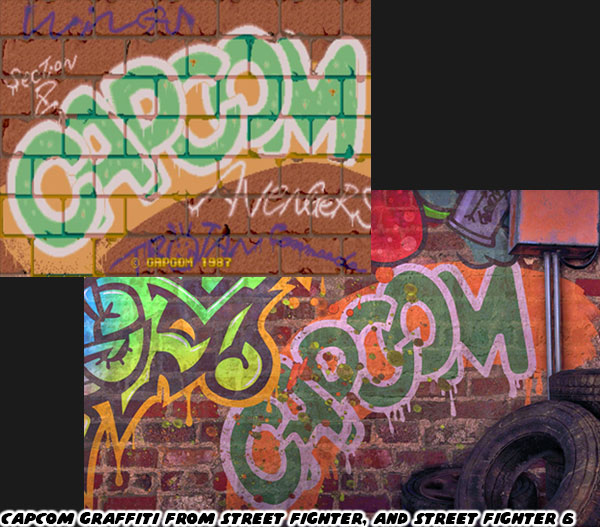

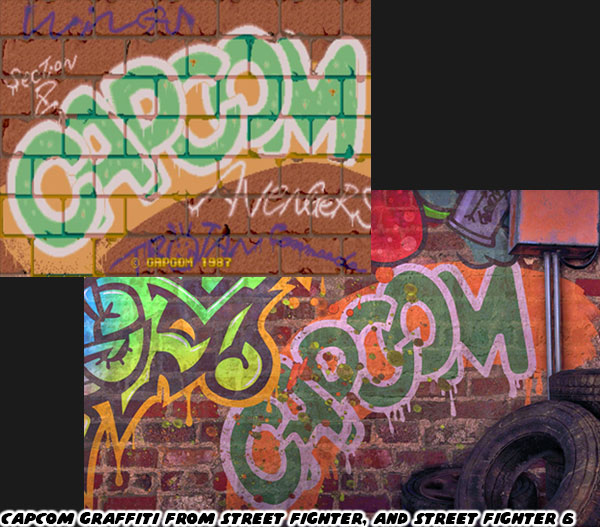

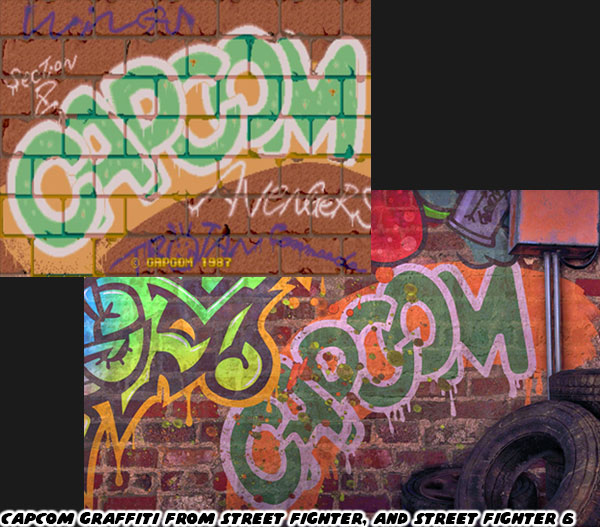

I don’t think modern audiences understand what a groundbreaking visual language Capcom was pushing with the first SF title screen. A brick wall was covered in tags of their previous hits; Section Z, Avengers, Trojan, and Commando. The massive company logo was right in the center. It oozed style, and attitude. Suddenly a fist punched through the wall, the unknown character turned his back, and we could see Street Fighter was embroidered on his jacket. It instantly grabbed your attention, and made you think that this would be the hardest title ever. Well at least I thought so. As I mentioned previously I played the original SF with the giant foam buttons. The intro screen was burned deeply into my memories. When I saw Capcom had recreated, and hidden the logo in SF6 I lost my mind. Every callout in Metro City was making me freak out. Capcom had learned to do something with graffiti culture that many other Japanese studios missed. Let’s talk about something that ran parallel with graffiti art.

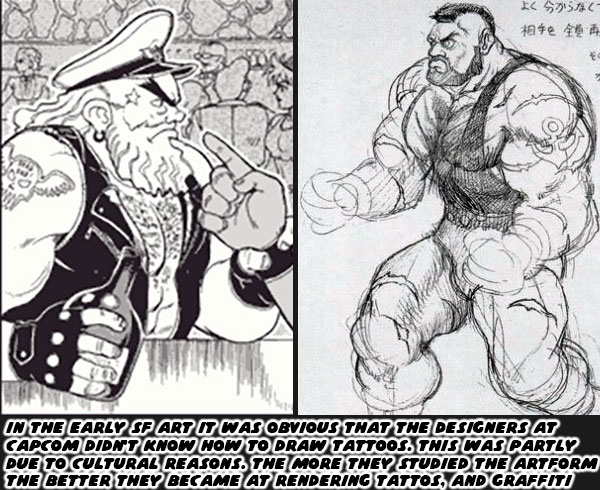

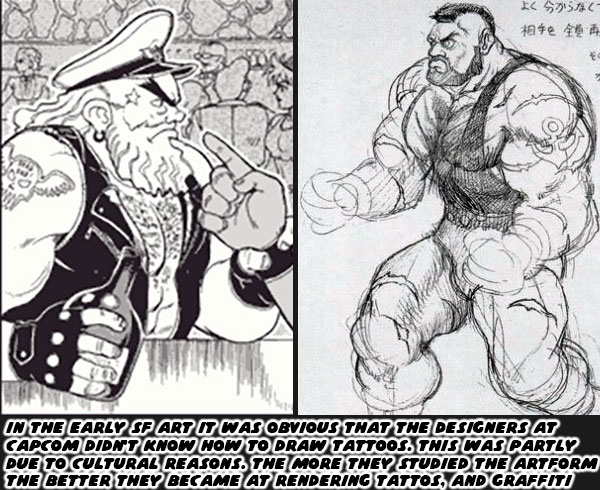

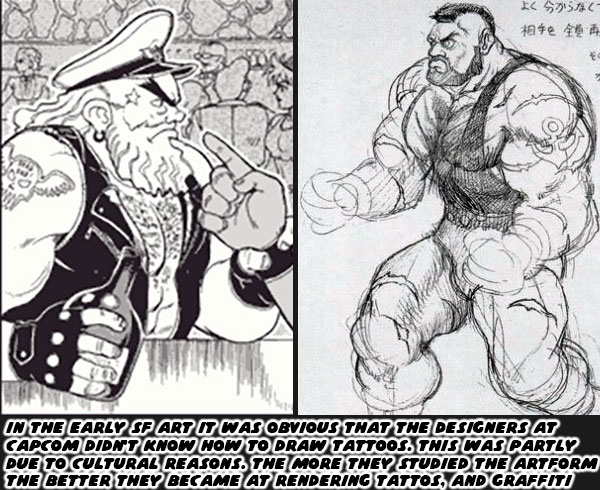

Drawing a character with a tattoo was another form of shorthand. In comics, cartoons, and manga people with tattoos were instantly seen as criminals, gangsters, or tough guys. The thing was that tattoos in Japan had a completely different connotation, and style from tattoos in the west. Intricate tattoo work in Japan was mostly associated with the yakuza. Not only that but the majority of the markings were covered up. They were only seen if a gangster visited a bath house for example. This was opposed to tattoos from the west where they could be seen out in the open. Perhaps on a shoulder, bicep, or forearm. When Capcom artists would create concept art for SF, and FF, they would try to draw a character with tattoos, but you could tell they didn’t know how, or what to draw. I remembered one biker/captain looking guy arguing with M. Bison (Boxer) he had a skull with wings, and a star on his temple. Or the early Zangief had a tattoo on his shoulder. Even the finished art had some yikes designs, like Birdie having a bright heart tattoo on the side of his head. It certainly wasn’t a very punk look.

The thing was that the artists working at Capcom, and other Japanese studios, started studying up on tattoos. They saw the rich tapestry of styles from artists all over the world. They saw how classic Western

Norman “Sailor Jerry” Collins helped shape a timeless aesthetic. It turned out that he was actually inspired by what he saw in Japanese tattoo art. This meant that the art form was cross pollinating across the Pacific pre, and post WWII. Society’s attitudes towards tattoo art had changed tremendously in the past few generations. It was the responsibility for the designers working at game studios to understand how to create authentic looking tattoos for their game characters. More than 30 years after the debut of SF Capcom was capable of creating passable tattoo designs that could be seen on gang members, and even used for avatar characters.

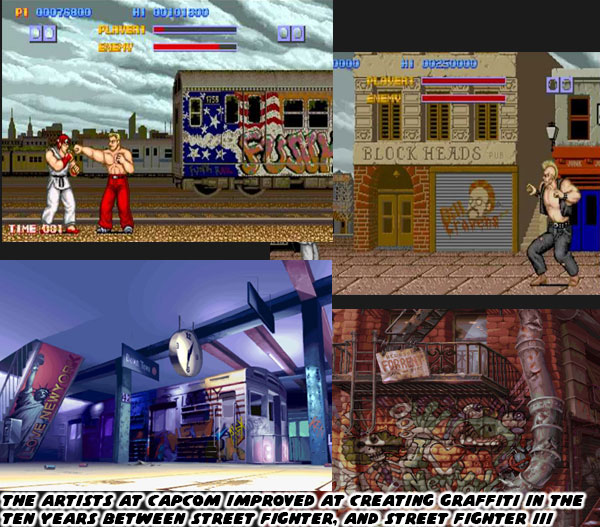

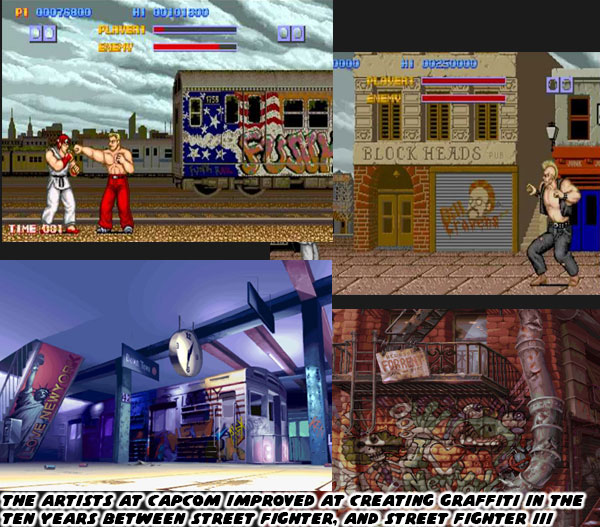

It was obvious that the more the artists studied a school of art the better they became at it. The graffiti used in the first SF was sometimes passable, and sometimes primitive. There were a lot of basic tags in Final Fight, but not really any good pieces. There was no graffiti art in SFII, and the only tattoo was Guile’s USA Flag. A decade after the first SF several stages in SFIII showed that the Capcom staff had grown by leaps, and bounds. The quality of the art, and animation, had grown as quickly as the skills of the programmers. There were several realistic tags, big productions, murals, and throw ups. Essentially the studio was showing that they knew not only the language of graffiti, but how, and where to present it on the stages. Some of these designs were recreated in SF6 for Metro City.

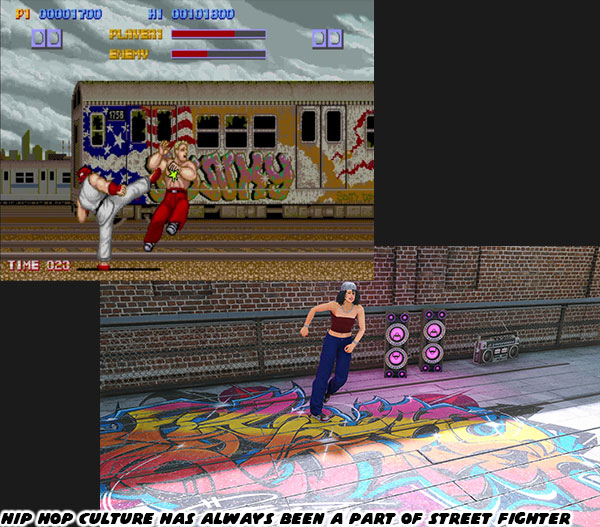

Fast forward almost 25 years after SFIII and Capcom was producing some peak graffiti art. It was displayed proudly on the SF6 intro screen, character logos, and all over the stages. It was apparent that Street Fighter 6 Director Takayuki Nakayama, and Producer Shuhei Matsumoto were not only fans of Hip Hop culture, but wanted to remind audiences that it had always been a part of the history of SF. In the early days the studio didn’t really know what they were doing. They were sort of emulating what they saw in movies, and on TV. Sometimes they missed the mark, but more often than not they got it right. Mr. Nakayama, and Mr. Matsumoto connected that history through the visuals, stage designs, NPCs, animations, and new characters. They also shared with audiences that graffiti was only one element of Hip Hop culture.

For decades game developers used only parts of the culture, rather than the whole. They might use graffiti, or rap music, or the dance in their game. These things were often disjointed, and poorly presented without context. The SF6 developers eased new players into how to play Street Fighter through the World Tour. They taught them the hundreds of little lessons through the pedestrian fights, gangs, and side missions. Something similar happened with Hip Hop in SF6. Metro City had some brilliant graffiti scattered throughout. They weren’t all freshly painted masterpieces, in rougher parts of town they were tagged up, and aged accordingly. There was a sense of realism with the use of the art. There were also b-boys (breakdancers) performing in the street, battling each other with their footwork. In the Battle Hub you could even put together some music on a turntable. Hip Hop had four major elements. Graffiti was the visual language, the dance was b-boying, and the music had two components, the dee jay, and the emcee. Rap was just one tiny part of a bigger cultural movement. In the ‘80s the Japanese developers were trying to emulate a culture they didn’t understand, or practice in their video games. By 2023 Hip Hop was understood universally as street culture.

Mr. Nakayama, and Mr. Matsumoto were not only aware of the four elements of Hip Hop, but they wanted to make sure it felt authentic in SF6. One of the ways they did this was through who was representing the culture in the game. Kimberly had embraced ninjitsu, her goal was to be a shinobi, the understudy of Guy. At the same time she wanted to infuse the secretive Bushin art with her own style as a graffiti artist. She had a sketchbook, she carried paint cans with her, and fought with them. Her hangout on top of the Metro City Police Department was covered in some amazing pieces. Every detail in her design told a story, and was supported by her environment. Just as I had mentioned that Luke’s stage design reflected his personality. Every SF character featured in the game received the same treatment. Capcom wanted to make sure that Kimberly’s representation mattered. She was not a washed up womanizing boxer, a struggling protégée for Ken, or an African tribal princess. She was a multi talented black teen. A student, artist and ninja star that would be influencing a whole new generation that looked just like her.

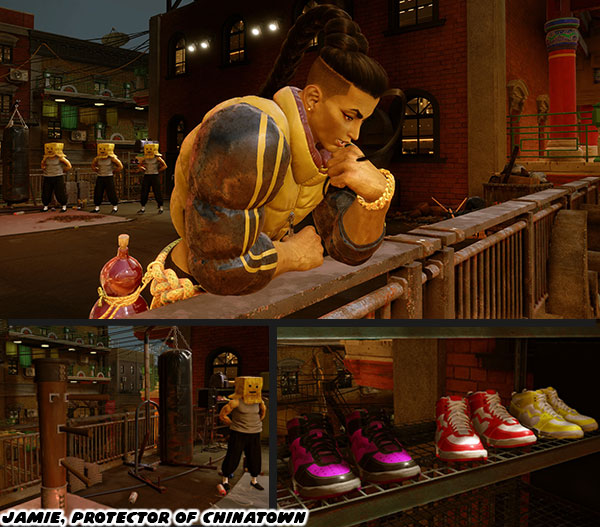

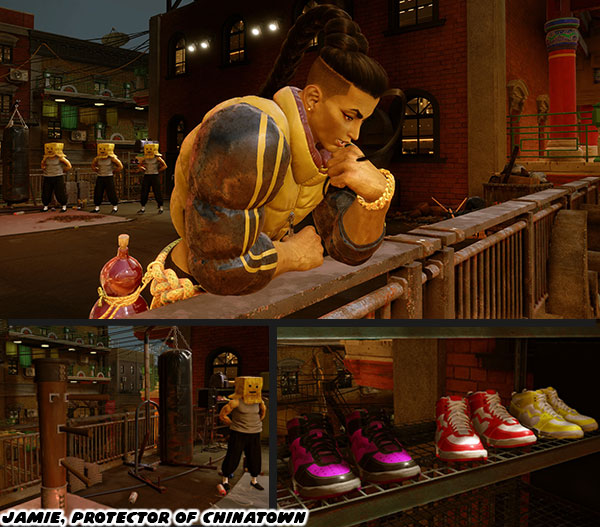

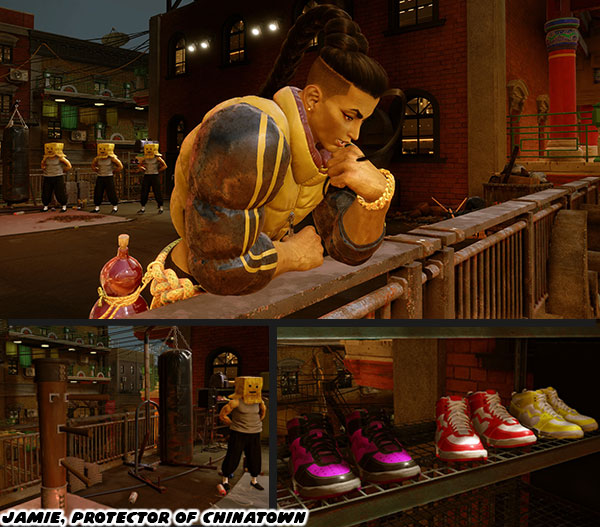

Hip Hop culture started in NYC back in the ‘70s. In one generation it became a global phenomenon. It did not belong to one race, or people, or country. With that said it was girls that looked just like Kimberly had been there since day one. They didn’t get any representation in fighting games until now. A similar thing could be applied to Jamie. The protector of Chinatown was a b-boy. Some of

the best dancers in recent years had come from Korea, Japan, and China. Seeing the Asian community represent, if not win in high level competitions demonstrated how powerful the culture was in attracting new audiences. Jamie had a foot in two cultures, the classic kung-fu practitioner, and the Hip Hop dancer. He was exceeding in both. It was the same amount of understanding, and respect that the developers used when creating Kimberly.

Jamie had the smoothest blend of martial art, and Hip Hop dance the world had ever seen. I had done

a deep dive on his design, and origins back in June 2022. There was not really too much to add to his look, and personality that I didn’t pull from his teaser video. The game did frame his personality in his stage design. He hung out on a Chinatown rooftop at night. Up there he had everything a young man would need; a weight set, punching bag, wing chun dummy, tiles for breaking, boombox, and collection of sneakers. The cultures, and representation that went into SF6 were handled much better than in the previous two games. It wasn’t the only progress the studio had made in this game. I’ll dig deeper in the next entry. Before I wrap up this blog if you want to find out more about the roots of Hip Hop culture here are three documentaries I would highly recommend. For graffiti art check out

the classic Style Wars. As far as dee jay music went I couldn’t think of a better film

than Scratch. One of the finest b-boy documentaries was called

The Freshest Kids. Thankfully they were all available for free on YouTube. I hope to see you back for the next entry. If you are a long time fan of Final Fight, or Street Fighter then I would like to hear your impressions of SF6. If you have never played any game previously then tell me your experiences in the comments section please. As always if you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment