But it was Hard Drivin’, and Race Drivin’ taught me how to drive. Asteroids, and Lunar Lander showed me how space was an endless adventure. It predated my love for all things cosmic. Gauntlet showed me that Dungeons and Dragons would actually be a great template for a video game. With that said however I always thought the skateboarding game 720° - the Ultimate Aerial Experience was possibly their most underrated gem. In my pantheon of arcade classics it was easily in the top 10, if not the top 5. It was hands-down the first game to get skateboarding right. Not only that, but it also reflected the era of ‘80s skating, and how far it had evolved from skating in the ‘70s. It was bold with its use of colors, music, and especially control. It was the first, and as far as I know, the only one with a joystick that’s fixed in a diagonal angle. Despite the greatness of the title, I thought the game was excessive in its difficulty.

Watching people chasing 720° high scores on YouTube confirmed to me that the game was just as hard as I remembered it. Every serious 720° arcade player on YouTube has a strategy in order to achieve their score. They don’t blindly start playing, and hope for the best. They share these details on arcade forums, but not necessarily on GameFAQs. This is essentially true of most arcade games. Unlike some home console games, you are rushed through the experience because you are almost always against the clock. A quarter only buys you a limited time, most games cannot be played perpetually. Those wouldn’t be appreciated by arcade owners.

The best studios knew how to balance the experience of playing, with the challenge provided. In order to get a high score, and thus secure your local fame you have to exploit the game in some way. Whether it requires you going through stages in a certain order, unlocking an item, or simply having the determination to practice the same techniques over, and over until it becomes part of muscle memory. Chasing high scores means that you can’t really enjoy the experience. You are essentially tasked to challenge yourself to do better, rather than appreciate the game. The first time I remember truly enjoying 720° was more than a decade after it was released. I was working in a college computer lab, and installed MAME (arcade emulation software) on one of the computers. I used it to play all of my childhood favorites with unlimited credits.

On one particular play through of 720° my character launched much higher than I had ever seen before, and he performed a McTwist. This was an inverted 540 spin° created by Bones Brigade alumni Mike McGill. I knew there were some basic vert tricks that could be performed on the halfpipe, but nothing as fantastic looking as the McTwist. Decades later I commented on the YouTube channels if there was footage of the McTwist that anybody had captured. Most players said they had seen it, however since it wasn’t worth too many points for high score runs then it was never recorded. That was when I decided that I wanted to get footage of this move because it was so cool looking, and not many had seen it. I couldn’t get MAME running on my home computer so I found that a lot of my favorite Atari games had been published in the Midway Classics collection. This was available to download for the Xbox One S. I remembered that I could screen grab, and record from the console so I paid a few bucks for the collection. It was well worth it, and in no time I found myself doing a deep dive on 720°, including capturing many of the moves, far more than I had even realized. I posted it on my Twitter, but probably should have put it on YouTube as well.

I discovered that nobody had put together a comprehensive list of moves on GameFAQs, or a strategy for the arcade game. There was one for the dismal NES version. I think part of the reason why was because many of the vert tricks would randomly pop out in the middle of a contest. Some tricks appeared depending on the speed, and angle that you approached the lip of the ramp. Some depended on what upgrades your character had, but none were guaranteed. I figured this must be the reason why nobody had ever written up a how-to for the arcade original. As a kid what really hurt me me about 720° (aside from wasting my quarters) was that it was built on an experience that no other game provided. The act of skateboarding is challenging, but at the same time rewarding. In order to separate gamers from their quarters Atari was cruel in their planning. They made it easy to skateboard, and perform tricks with the use of only two buttons. Anybody with a quarter could skate like a pro.

To really hook players Atari created the ultimate world to skate in. They introduced a place called Skate City. Every block its own brightly-colored skatepark, complete with gaps, ramps, and wedges. Massive speakers in the heart of the city provide endless skate-punk tunes. There are no signs prohibiting skateboarding, or skate stoppers bolted to any legs. This is the world that skaters wish they had. Skateboarding, as you know, is not a sport, it doesn’t have rules. Nobody can “win" at skateboarding, it never has a season, or championship, at least not in the traditional sense. It is an art form, a physical activity, and a culture. This culture comes in conflict with society many times in the real world. The act of skating is seen as destructive, just like graffiti art. It is not seen as creative expression in most cities. Atari’s version of Skate City is heaven to me now, as much as when I was a kid. Who wouldn’t want to explore this place? There are endless lines you can paint, nooks to find, and various spots to perform tricks on I needed to see every inch of the map. This was why I was willing to put quarter, after quarter into the machine.

You can earn points while exploring skate city, but if you want your initials on the leaderboard you have to enter one of the four available contests. Atari made sure to encourage players not to waste time in the streets by putting a timer at the top of the screen. Once the timer runs out the game alerts you to “Skate or Die." While the slogan may have initially appeared on a sticker sold on the back pages of Thrasher magazine, it pretty much entered public consciousness thanks to the game. When the warning appears a swarm of angry bees start to chase the player. At first you can skate faster than them, but after a few seconds they begin to speed up, and even take shape like a cartoon syringe to sting players, and end the game. If you don’t have a ticket (many times I did not) there was no way to enter the contest, and escape the bees.

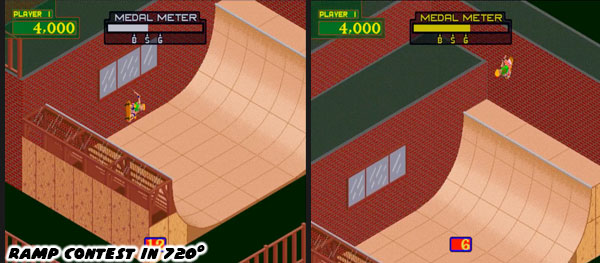

Players begin the game with a single ticket, and must perform tricks to earn more tickets to enter the four available contests. The contests themselves were a good cross-section of skateboarding events from the ‘80s, with a few liberties thrown in. The most popular contest, at least to me was the Ramp contest. It featured a halfpipe next to a brick building. Players could perform an assortment of moves on it, including every possible spin combination. Depending on how fast you rotated the joystick clockwise, or counter-clockwise your character could do a 180°, 360°, 540°, 720°, 900° spin, or more. No only that, with enough speed you could even leap onto the rooftop, and jump back in to earn outrageous points. The timer in each contest was constantly going down, meaning that in this event you only have a few seconds in which to earn enough points to score a medal; Bronze, Silver, Gold, or no medal at all. I’m certain that most people that played the game in the ‘80s wish they could have spent more time just trying out all the ramp tricks.

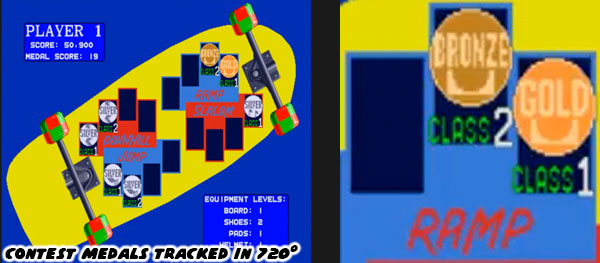

As the game advanced the contests required higher scores, or faster runs, in order to earn any medal. Several of the high score runs on YouTube don’t focus on medals, but rather what tricks score more points. It is possible in some events not to finish a course, but instead use the available time do as many tricks as possible. The ramp contest featured the most popular exploit in the game. Before dropping in it was possible to have your character bounce off the wall, and “grind" on the edge of the ramp earning an incredible bonus. Then you simply skate up each wall, and allow your character to slide down the ramp. While this kills the purpose of actually riding the ramp, and spinning, it rewards far more points, and guarantees a gold medal each time. The collection of medals are recorded on a skateboard deck, completing the theme of the experience.

The other contests are pulled from traditional skateboard events. One of them is the slalom. In it players have to race down a wooden track, while moving in between flags as fast as possible. It is very easy to overshoot the flags, and end up sliding off course. Slalom was one of the more popular old school skateboard events going back to the early ‘70s.

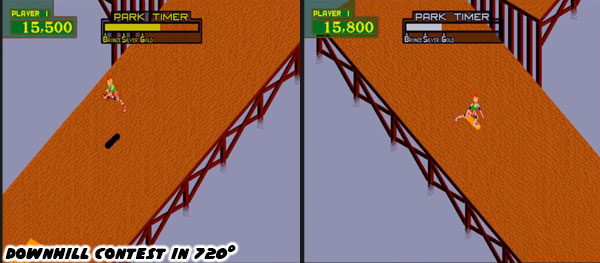

The other race in the game is downhill. Again this is sort of based on actual skateboard racing. However instead of racing on the street against a group of opponents it’s the player against the clock. Gamers have to navigate a steep wooden ramp, and try to get down as fast as possible. Players can clip corners, and jump into further sections of the ramp, rather than try to ride them down completely. Like the slalom it is very easy to go off the edge of the ramp because you miscalculate the turns or jumps.

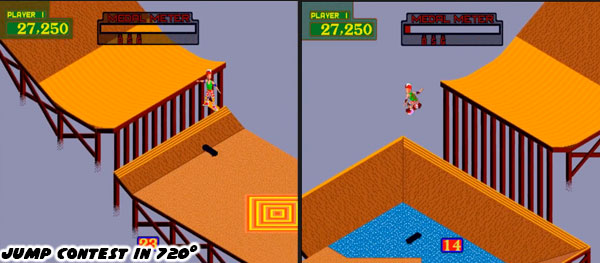

The fourth competition in the game is called Jump. It is the only event in the game that was not based on a traditional contest. Instead players have to navigate a steep ramp, similar to downhill, but with a ramp at the end of each platform. Players are rewarded for landing on a small multicolored target. Of all the contests this is by far the hardest to medal in. The target is not visible until you have already jumped. Making it very easy to overshoot completely. The game does give you a hint as to how far out to jump, and in which direction. A yellow diamond shape is painted on the run up ramp, if you line up right over the diamond you are guaranteed to at least be headed in the right direction. A large diamond means that the player has to jump, and spin out as far as possible. A medium-sized diamond means you don’t have to go as far. And a tiny diamond just means to let your character drop off the platform. Sometimes the diamond is pointing diagonally, which means you have to carve across the ramp just before your jump. Then there are double diamonds, which let you know if both are a jump, or if the first is a drop, and the second is a jump. Like I said it’s very difficult to score here, as there are no do-overs in the event.

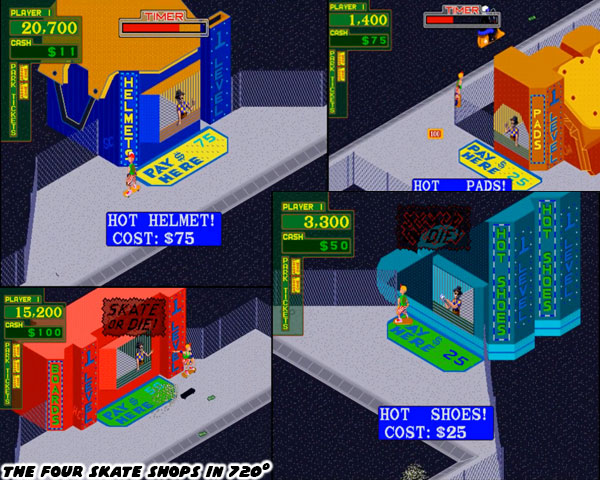

The only way to get good at 720° is to play it over, and over. Which of course was what Atari, and the arcade owners were hoping for. As I said earlier there was a way for players to exploit a part of the game so that they could chase competition tickets, and high scores. The ramp glitch I described was one way. The other was by purchasing certain items. Contest money could be used to purchase a helmet, skateboard, shoes, or pads. Each one of those items helped increase the stats of the player. The shoes for example allowed the player to jump higher. The helmet allowed them to spin faster.

Pads could be used to recover faster from accidents. The board allowed you to go faster. There were three tiers of each item that you could buy before the store that sold them closed down. As a fun aside the stores themselves looked like a giant version of the item. The shoe shop looked like a giant pair of canvas sneakers. The helmet shop looked like a giant helmet, etc. You didn’t really have to purchase the Level 3 version of each item in order to maximize your score output. Many of the best players suggest to only get Level 1 or 2 of certain items, and in a specific order.

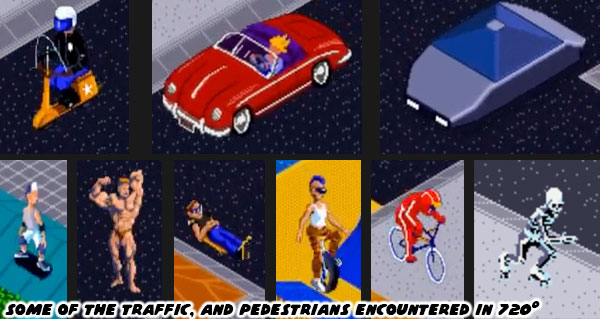

Of course navigating Skate City wasn’t without its risks. There were other skaters to compete with on the parks throughout the city, as well as various other pedestrians blocking the sidewalks. Rival skaters, kids on BMX bikes, punks on unicycles, bodybuilders, and even frisbee players could all knock over our skater. Yet a savvy player could actually time a boneless jump, and land on pedestrians instead. This was an interesting detail about the game. The character could not ollie, and would actually plant his foot in order to leap into the air, or go higher on a ramp. These tricks were known as boneless, no comply, or fast plant, depending on whether the player grabbed the board or not. Of all the pedestrians the one that stood out the most was a roller skating skeleton. At first glance you might think it’s a person in a skeleton suit, until you crash into him, and he collapses into a pile of bones.

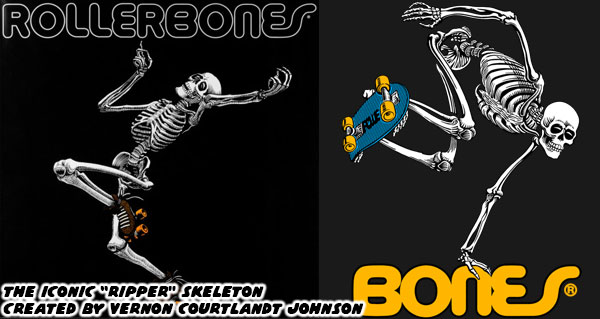

The character was undoubtedly based on the “Ripper" skeleton created by artist Vernon Courtlandt Johnson, who created a number of pieces for Powell Peralta skateboards. To me VCJ is a god, and easily one of the biggest influences on my art. I’ve mentioned this before on my blog. While many skaters may equate the Ripper with skateboarding, some of his earliest art was used on roller skates for Bones wheels. This very rare shout-out was used by Atari when they put the character in the game.

The more I played 720° in the arcade, years later on MAME, and decades later on the Xbox One S the more I appreciated it. As I pursued footage of the McTwist I began absorbing all sorts of details that had been lost to me previously. It made me dig in a little bit more into its history. I’d like to share a lot more on this game, and my other favorite skateboard games over the next few blogs. I hope to see you back for that. If you would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment