The first game featured today should be enshrined in the gaming hall of fame. Shadow of the Colossus (2005) was an international sensation when it was released. Very rarely were games so universally accepted that they required little if any localization. In order to be played the game required nothing more than the time, patience and practice. The game did not really need dialogue or lengthy cut scenes in order to be enjoyed but it didn't hurt that they were included. Fumito Ueda's tragedy featuring Wander, Mono and a very brave horse named Agro showed the industry that the giant monster could be a stand alone genre. The game used every lesson taught by giant monster films and classic literature and then created an original play experience out of them. The game isolated players in a forbidden land. They were enclosed by high cliff walls that couldn't be scaled and an ocean that could not be crossed.

Players could do nothing more but explore the environment and search for enormous creatures that were part living and part stone. Wander was equipped with two weapons, a bow and arrow and an enchanted sword. The creatures were invulnerable to both weapons with the exception of some strategically placed magical tattoos. When Wander stabbed the colossi on those tattoos the monsters could be defeated. Players did not know about the rules of combat regarding the colossi or how the sword worked. They were trained by the levels on how to run, scale, roll and jump around the environment. Little by little everything in the game was learned simply by playing rather than by going through a tutorial. Knowing how to perform multiple actions would come in handy as the colossi they fought were harder and harder to reach and defeat.

Just one of the genius details in the game design was in creating tension before each encounter. The levels were spread out far enough for players to develop a sense of isolation as they went from battle to battle. The music and sound effects reflected this emotional pull. Each colossi was introduced in a short cinematic that showed players the enormous scale of the creatures. They were very intimidating and no two were exactly alike. The music would pick up and increase the pressure for the duration of the battle. The colossi would focus their attention on the player with bright unblinking eyes. They would search for them, stomp and scratch at them as they ran and hid in corners of temples and pits. It was an amazing action experience that was highlighted by the giant monsters themselves.

Ueda had created a universe filled with mythical creatures that appeared to be alive. He left enough clues on each level to let the origin of the creatures be explained. At some point the colossi might have been considered gods to the ancient civilization that built the temples. Prior to the colossi there was a single creature that inspired fear in the old tribes. Dormin was a dark, horned god that used to rule over the land. He was split into 16 pieces that each became a colossi. During the game it was revealed that Wander was slowly becoming possessed by Dormin as he defeated each of the colossi. On the last stage Wander underwent a transformation. Players could suddenly control Dormin against a group of tribal elders. This twist to the plot and game play was sublime. Players had no idea that they would end up becoming the creature that had been leading them on. Shadow of the Colossus redefined the giant monster genre and ended up influencing titles yet to come, not the least of which was Nintendo's award-winning game The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017). It turned out there were still other lessons that could be learned by playing with and against the creatures.

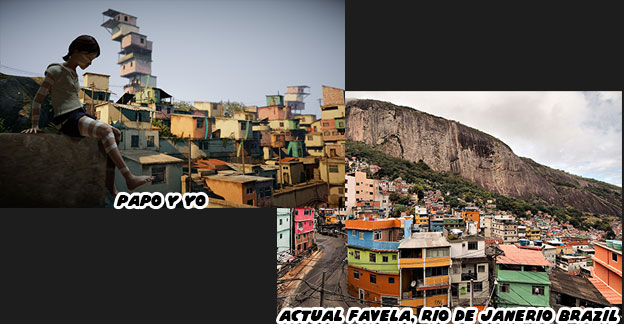

Vander Caballero created the indy hit Papo y Yo (2012). Minority developed an experience that captured the art of storytelling in gameplay as well as the biggest Triple-A studio. The game revolved around a unique relationship created between a monster and a little boy in a Brazillian favela (slum). The game turned the imagination of the young Quico as gameplay elements. Quico was searching for a way out of the favela while trying not to irritate the monster Papo. The game was actually an allegory for the relationship between the Vander and his alcoholic and abusive father. Quico could make walls turn to stairs and have building stretch as if the world were made of toy blocks and Silly Putty. Papo was available for some of the puzzles by triggering doors, traps or simply helping Quico reach higher places. The exploration and imaginative puzzles was only part of the reason that gamers wanted to find a way out of the favela. The sense of isolation that Ueda created in Shadow of the Colossus were mirrored in Papo y Yo. The favela was modern, it had color and personality but it also appeared like a prison. The walls were made up of the homes of people that seemed perpetually absent from the world. As far as the eye could see there were the walls, leaned onto the next, piled on top of each other. Despite the brilliant graffiti murals it was an oppressive site. In Shadow of the Colossus Wander would have to travel through the ruins of castles and temples that were even more imposing than the colossi that dwelled within. These design choices were part of the psychology of the games. The isolation created by these locations made Wander and Quico more sympathetic and their struggle more impressive.

Papo had a weakness, he enjoyed eating frogs but when he did he became a raging monster who did nothing but hurt and destroy. Papo could be pulled out of his rage by feeding him melons, but like sobriety to a person with a severe problem it was a constant struggle. The contrast between the friendly Papo and the flame-engulfed monster was a shock. Players learned to keep an eye on Papo while trying to figure out the next puzzle. The tension in the game was palpable. Players were tiptoeing around a ticking time bomb yet rather than stop playing they were compelled to help Quico escape. The emotional draw of the characters pulled audiences into the world. It was similar to the attraction behind Shadow of the Colossus. Wander needed the player to help him defeat the colossi and resurrect Mono. Quico needed to find a way out of his nightmare. Both games taught audiences to be brave and even defiant in the face of adversity. It also forced the players to think about their own mortality. The psychological elements from the giant monster myth were done equally well Papo y Yo. The isolated environment, the layers of detail that brought players into the world. The indestructible creature. When these things were combined they helped create a sense of primal fear. The fact that the game was created as a coping mechanism to help with those that came out of abusive relationships was superb design.

There was more to the giant monster genre than simply running from or battling against them. It was something that had been overlooked in the series thus far. A completely different contribution to gaming that could only be provided by the creatures themselves. Entirely new styles of gameplay had to be created so that the player could wreak havoc on an unsuspecting population. To say that the newfound power went directly to the heads of the players would not be far from the truth. In the next blog we shall look at the games that turned gamers into virtual gods.

No comments:

Post a Comment