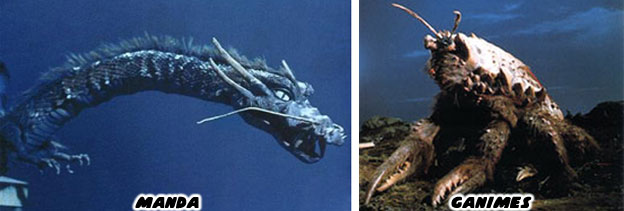

When Godzilla was first designed the creators were looking for dinosaurs as their main inspiration. As sequels were released Godzilla needed allies as well as new opponents to fight on Monster Isle. Designers went back to work crafting monsters that were rooted in nature and even mythology. The serpent like Manda was based on classic Eastern dragon designs, the spiky Ganimes on the other hand was more like a giant crustacean. The Japanese seemed to be going through the same creative roadblock of Western movie producers. Gigantic versions of natural creatures were good but lacking. Godzilla did not quite look like any actual dinosaur and that lack of connection seemed to work. The better monsters had more fantasy inspired cues and took many artistic liberties.

Toho studios hit their stride in 1964 when they released King Ghidorah, the Three Headed Monster. They combined classic and science fiction designs into one creature capable of giving Godzilla and his allies a run for their money. The gold scaled three headed dragon, possibly a wyvern, was from Mars, sometimes credited as the uncharted Planet-X. Toho was combining extraterrestrial elements with their version of giant monster storytelling. This opened up the daikaiju format exponentially. The creatures could come from nature, or they could be the result of a mutation brought on by radiation, or they could even come from outer space. The rest of the world ran with possibilities but none did it better than Toho. Godzilla and the other daikaiju were proving to be extremely popular with young audiences. Kids loved the spectacle of the monsters destroying models. They understood that Godzilla was not a villain and the destruction was collateral damage from his battles. Toho began introducing villains that were unlike earlier daikaiju. The new monsters began developing personalities. Little by little the daijaiku were becoming like the classic Hollywood monsters. They were even developing a following the world over. Toho was listening very closely to their fan base and began designing villains that were multidimensional as well. Godzilla's next truly worthy challenge would appear in 1971. Hedorah, the Smog Monster was a creature born from toxic pollution. It polluted the air around it and reduced cities to sludge. It was actually a very powerful opponent and like King Ghidorah it managed to give Godzilla a good thrashing in their first meeting.

Hedorah was much more than the Blob (a 1958 cult classic) with eyes. It was drawn from the zeitgeist of environmentalists. Those too young to remember the atomic weapons used against Japan were keenly aware of the effects that pollution were having on their health and homes. Toho used the film to educate kids on the dangers of pollution as much as it did to entertain them. The generation being raised on giant monster films were also absorbing lessons from comic books, manga, anime and cartoon shows. These young men and women would become the early generation of game designers. They went through a similar learning curve that movie studios had when they first began working in the giant monster genre. Some of the challenges of making a convincing giant monster was a technical one. Software and hardware were very limited in the late '70s. It was tough to get audiences to commit to suspension of disbelief when they were looking at boxy shapes instead of creatures. Developers learned that visuals and effects were only part of the draw of the giant monsters. Control was a make or break point for every title. The ones that found the perfect balance of control while managing the expectations of gamers did the best. It took almost 30 years for graphics and control to reach a point where audiences could be completely engaged in the experience and accept the giant monster as more than a backdrop.

If a current generation player turned on their game system they could expect to be floored by the visuals of a creature like the Hekaton monster from Bulletstorm. The player may not realize that the creature came from somewhere beyond gaming, That somewhere was a combination of influences from science fiction cinema and giant monster movies. The developers at Epic Games had used their insight when designing the Locust aliens in the Gears of War series and were now pushing the envelope as to what was possible. Only when they had enough experience, from a Gears of War trilogy, were they able to create Hekaton in Bulletstorm without breaking the engine or game play.

Even the games that were not violent or graphic were pulling tremendous cues from the giant monster genre. Pokémon for example was a mostly nonviolent battle game targeted at younger gamers. The series had introduced several monsters that were inspired by daikaju legends. Some were subtle and some were overt. Tyranitar could be considered the Godzilla equivalent of the Pokémon universe. As if it were not obvious the series even introduced a Mecha Tyrnaitar as well. The use of robotic daikaiju dopplegängers first happened in 1974 when Godzilla fought Mechagodzilla. Since that time there has been a robot equivalent for almost every major Toho monster.

Even titles that did not feature giant monsters were still drawn to the appeal of the genre. Since 2007 Team Fortress 2 had pitted the Red and Blue armies against each other. In 2012 Valve introduced a third army with the Mann vs Machine multiplayer campaign. The new army was made of robotic copies of all the main military classes. Fans of the game went wild at the announcement. Of course the older players clearly knew where Valve had drawn inspiration for the new army.

Some of the best games of the current generation have exploited the giant monster in one way or another. Several of the most memorable action sequences in first person shooters used the creatures as set pieces. The Leviathan battle from Resistance 2 and the Thresher Maw versus the Reaper from Mass Effect were among the best moments on the new console shooters. Mass Effect was notable for pitting enormous science fiction technology against gigantic alien lifeforms. They had clearly been paying attention to what Toho had contributed to the genre some 40 years prior. The creatures and robots featured in those games had an incredible scale and would have been impossible to render on older hardware. Their purpose however was more than simply for the sake of showing off the horsepower of the new consoles. They were the set pieces that designers had been chasing for over a decade.

Many first-person shooter game designers wanted to give players a feeling that they really were a one-man army trying to save the world. It worked previously by putting the player on another planet or featuring backdrops that filled the entire horizon. For the first time though programmers were able to animate creatures that actually filled more than the field of vision for the gamers. These colossal beasts could now also interact and create a game play challenge. Insomniac and Bioware studios maximized the impact on players by making sure the world presented in their games was as realistic as possible. They included the details to support the environment that players were fighting through as well as the technology that allowed them to battle alien lifeforms and humongous creatures. The soldiers and teammates in the game had personalities and were written well enough for gamers to relate to them. When the gigantic creatures appeared the players were ready to stand side by side with their allies.

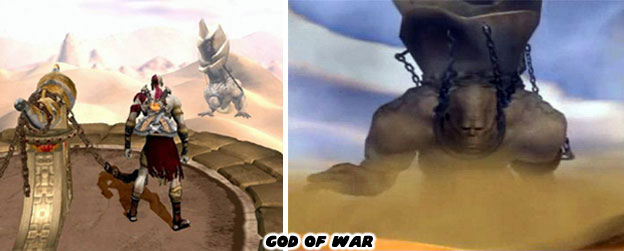

This type of interactivity, immersion and emotional draw was not limited to the FPS format either. Role playing, adventure and fantasy titles had also been pushing the limits of what was possible for gamers. The original God of War actually tapped into the origins of the giant monster mythos. The search for Pandora's Box took the Kratos to the ends of a deadly desert. It was where the leader of the Titans, Cronos, had been exiled. Cronos was also of the father of the Greek pantheon. Because he was jealous of their power he ate each god after they were born. Zeus escaped this punishment and returned with full power to release his siblings and imprison Cronos and the other titans. The version of the legend was worked into the plot of the game. There was a mountain strapped on his back as punishment. The mountain was actually temple to Pandora wherein there were traps and puzzles to challenge players.

The Playstation 2 hardware was not powerful enough to render massive characters, instead Sony Santa Monica used scale and perspective to trick gamers into thinking that Cronos was as enormous as described. In the first full shot of the character he was presented many miles from Kratos. Then as he got close the team framed just part of his face on the screen. They created a portion of the level on an outcropping of the mountain. As the camera pointed down the gamer could see a portion of the massive chains that bound the titan. They could also make out an arm and head of Cronos as he wandered the desert. Since very little of the titan was actually shown the engine could animate just those part while keeping the rest of the level static. The illusion was very well done. Producer David Jaffe and his team were fans of giant monster films and used their composing techniques to make the gods in the game look as massive as possible on the hardware.

The final level of the game featured a battle with a gigantic Ares and Kratos. Again, using the tricks of scale and perspective Sony Santa Monica created a miniature version of Athens for players to walk around. The hardware was able to render the level by scaling down all of the scenery, reducing the details and bordering the edges of the level with a bridge and mountain range. The studio introduced a convincing pair of giants that still moved like regular characters.

Eventually the hardware caught up with the vision of the designers. When God of War III was released on the Playstation 3 the Titan set pieces had no equal. Cronos and several other titans featured in the series all became self-contained levels. They walked around Tartatus, the underworld of Greek mythology, all while swatting at Kratos and trying their best to crush him.

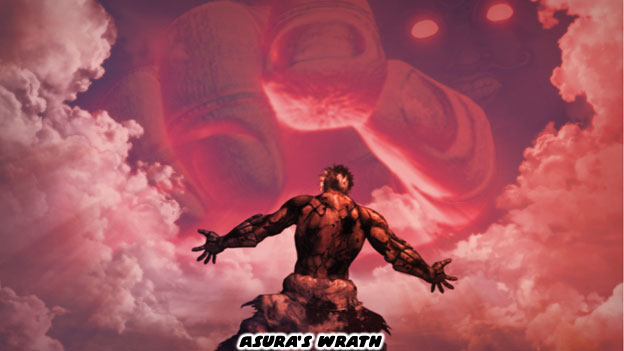

Other studios were having a field day with the processing power of the new consoles. Capcom shattered the bar when it came to the scale of giant monsters in a video game. In Asura's Wrath the players were not battling giants or even titans but instead planet-sized mechanical deities whose fingertips enveloped entire continents.

Capcom became very successful at creating games that featured a strong contrast between playable characters and giant monsters. We shall look at what they learned about monster, character and game design during these releases in the next blog.

No comments:

Post a Comment