Design cues for the main characters had to tell a story. The clothes the characters wore were not always clean uniforms from a school or dojo. Some were humble, shoeless, giving up their worldly possessions in pursuit of the battle. Their uniforms were worn out, messy with torn sleeves. Others wore street clothes, jeans and heavy boots. They fought dirty, with knives and chains. Players could tell that these characters were not new to the fight game. But what about the fighters that represented a new movement, one which did not represent one particular school or form? Was it possible to capture the spirit of a modern fighting master without betraying the legacy that the martial arts and pop culture had established?

The two biggest fighting game publishers, Capcom and SNK tried to answer that in the late '90s. Both studios had grown tremendously since they helped establish the fighting game revolution at the start of the decade. Street Fighter II, Fatal Fury and the Art of Fighting were released between 1991 and 1992. The groundbreaking fighting games introduced new play mechanics to audiences and a library of memorable characters. By the end of that same decade the traditional martial arts master featured in those games had become tired and predictable. The genre needed some new ideas. What the studios did was look at what had happened in the fight game and found a way to incorporate those changes into their own universes.

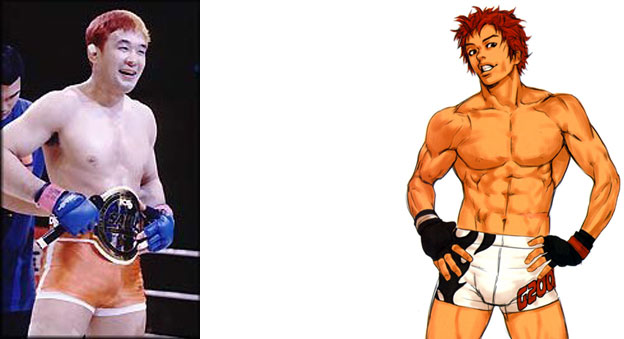

The era of the "Mixed Martial Artist" or MMA fighter had begun and fighting games needed to reflect that change. It took almost a decade for the developers to catch up to those changes. Ryu, the karate inspired star of the Street Fighter series was an homage to the traditional martial arts heroes that the developers at Capcom had grown up with. SNK tried to take a step back away from the archetype in the game Buriki-One. The title from 1999 introduced a new main character named Gai Tendo. He did not seem to have any particular style or affiliation but was adept at striking and grappling. Gai reflected the new breed of MMA fighter that had become so wildly popular in Japan. They were energetic, stylish and exciting to watch. Unfortunately the game did not reflect that sentiment. It was slow and cumbersome. It also did not receive wide exposure. The arcade scene had been dwindling in the US for some time. The game itself suffered from dismal 3D graphics and odd controls, which were the major features of the best fighting games. Despite those things Gai stuck around and managed to return as a playable character in King of Fighters XI.

The introduction of Buriki-One went hand-in-hand with the rise in popularity of MMA tournaments. The K-1 series in Japan started in 1993 was labeled for its karate, kickboxing and kung-fu roots. The tournament was descended from a different format. Seidokaikan, was a full-contact knock down karate format that incorporated rules from professional kickboxing, including uses of knees and throws, until it became the K-1 tournament that people knew. The PRIDE Fighting Championships started in 1997 but closed a few years later. Both K-1 and Pride had huge followings overseas and fighters actually flew in from around the world, including North and South America in order to compete. Audiences appreciated the diversity of fighters and treated them with tremendous respect. In the US the tournament scene did not take off as quickly and fighters were not well regarded. The Ultimate Fighting Championship or UFC series also began in 1993 but did not have the rules or weight class divisions that it currently had. Gai Tendo was reflective of the Japanese MMA tournaments. He was inserted into the King of Fighters universe to represent the modern fighting legends, including people like Kazushi Sakuraba. These modern fighters were more flashy than Mas Oyama or Yoshiji Soeno were when they inspired the legend of Ryu and the mythos of Street Fighter.

The MMA star seemed to rise out of nowhere and captured the hearts of millions of fans. The legend of Sakuraba had actually been centuries in the making, only many people didn't know it. This series will explore the influence of the grappling arts on fighting games and the community. I hope you return for the next entry! As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment