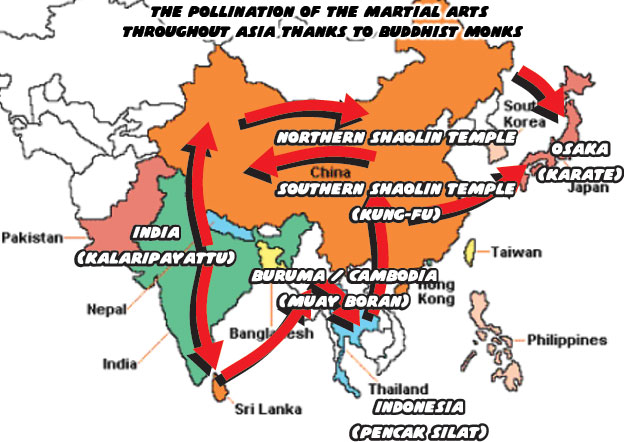

Something that contributed greatly to the development of the fighting arts in South and South East Asia was actually the terrain and weather. The further south in Asia had a much higher level of precipitation. During the monsoon season rainfall could be measured in meters rather than inches. Portions of Japan and China were well within the monsoon belt as well but the majority of the rainfall was concentrated over areas closer to the ocean, such as Thailand, Cambodia and Myanmar (Burma). Of course the surrounding islands and peninsulas of Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines were no strangers to wet climates. This heavy rainfall translated into lush vegetation, thick jungles and heavy forest canopies. Travelers had to be wary not only of wild animals but also of bandits that could be hiding at every step of a journey. This terrain also changed the way wars were fought and won. Larger armies from the North used to controlling massive areas of space with the aid of advanced long-range weaponry such as catapults and crossbows were at a loss in jungle settings. Due to the dense vegetation the wars in the South were fought in close quarters, man-to-man. The armies that combined practical close-range weapons with deadly martial arts training were all but guaranteed victory. The way men fought and trained in the martial arts in the South was much different than what Bodhidharma took with him into China. Heavy armor favored by Chinese, Mongolian and Japanese forces were too cumbersome to use or even wear in the hot tropics. Fighters had to be free to move, use the terrain to their advantage, and strike whenever and wherever an opportunity presented itself. As Budhhism traveled through Bangladesh, into Myanmar and Thailand the fighting forms of the monks were dissected and portions were combined with native techniques. The hybrid of systems worked extremely well with stick, sword and shield fighting. Even without weapons the forms that grew from the tropic regions was deadly in its efficiency.

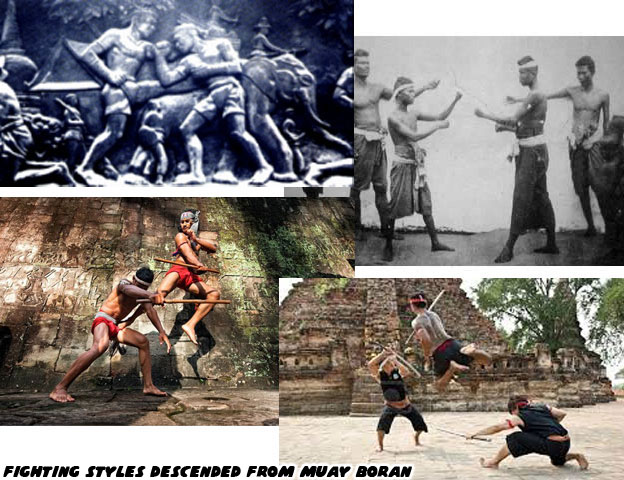

The art of "Eight Limbs" had a lineage that went back thousands of years. The bare hand fighting forms which made liberal use of elbows, knees and clutches were brutal. They were dangerous in the arena as they were in the battlefield. The form known as Muay Boran in ancient times was practiced by the personal bodyguards of the kings. It eventually went beyond the walls of the imperial palaces and changed into what the modern world now knows as Muay Thai. There were countless regional iterations of the striking arts, called Mai Mae, Luk Mai Muay Thai, Bokator, Kun Khmer and Pradal Serey. Each one could be identified for its many victories on the battlefields as well as in the fighting arenas.

Yet that was not the only offshoot fighting art that evolved in Asia. In Indonesia Pencak Silat, sometimes called Silat was a word used to represent the indigenous martial arts of over 800 styles from the thousands of islands that make up Indonesia. Betawi for example is an aggressive striking form whereas Cimande is focused on flowing combinations. The main forms originated in Sumatra and Java. Silat was used to defend the natives from Northern aggressors as well as from foreign invaders. It incorporated many unique stances, tight sweeping strikes and rapidly changing angles. These kept opponents off guard, baffled invaders and made sure that the Indonesians enjoyed their independence for centuries. The style, like those from the other coastal countries in Asia would not have worked while wearing armor or yielding heavy weapons. It was about being light and fast so swords were more like daggers and shields were light and portable. When the British, Dutch, French and other imperial armies began to colonize the port towns the Indonesians did their best to preserve the art form. The would-be conquerers from the West did their best to supplant the languages, temples and cultural icons of the Asians but this did nothing more than make them dig in deeper to preserve their heritage. As a result Silat not only survived into the modern era, its practitioners were still considered some of the most lethal fighters in the world. Pencak Silat, like Muay Thai was descended from combat, it was not a form for sport, exercise or self-improvement. It was meant to kill and thus retained its dangerous overtones.

Silat could not necessarily be considered one of martial arts directly influenced by the Buddhist monks traveling through Asia. Indonesia is the largest Muslim nation on Earth and has been for some time. The evolution of Silat was nonetheless influenced by traders and settlers from Northern regions. Kung-Fu developed striking arts that were inspired by the grace and beauty of nature however the fighting arts in South East Asia were inspired by centuries of bloody conflict. As such the fighters from South Asia gained a reputation for being dangerous combatants. The masters of kung-fu and karate could find a way of having a friendly sparring match, perhaps the first to drop an opponent or even the first to land a solid strike could be declared the winner. By contrast those that fought in Muay Thai tournaments were looking to break opponents. Blood was the measure of success, fighters would wrap their knuckles in cord and sometimes crushed glass so that they would be able to tear the flesh off opponents. Even modern matches have lost little of the lethality of ancient rules. Some strikes have been outlawed in organized competition but even without these strikes only the most dedicated fighters could hope to achieve a level of champion. For those that want to see what sort of brutal punishment the top fighters could unleash against each other take a look at the infamous "Elbow Fight" between Sakmongkol and Jongsanan at Lumpinee Stadium in Bangkok. It was the fifth time that the two had fought each other. Round after round the two ate elbows like a kid eating candies at Halloween. Fans of this level of fighting could be considered sadistic while the fighters were clearly masochists. No amount of punishment could satiate either group. The spectacle of professional competitions and the legend of underground Muay Thai tournaments spread far and wide throughout Asia. Only the most foolhardy martial arts master would dare seek out these men in a fight. More "refined" cultures like those in China and Japan looked down on the barbaric combat from the South. This repulsion for the hyper-violent Southern eventually turned into legend. The only way that a master of the "modern" arts could prove their skill was to seek out new challengers, especially those from Thailand.

In cinema kung-fu had become a mainstay of fighting forms. Action films the world over relied on the classic Asian arts to make heroes appear unstoppable. Yet every decade there seemed to be an artist to come out of nowhere, using a different art and redefine how movie fight should look. Muay Thai rose to prominence on the heels of the film Ong Bak in 2003. In it director Prachya Pinkaw made a moderate-budget film that highlighted the fighting and stunt abilities of Tony Jaa. Tony became an overnight sensation in action film circles and created a buzz that was comparable to the early days of Jackie Chan and even Bruce Lee. Almost a decade later director Gareth Evans featured Silat through the skilled hands and feet of Iko Uwais, The Raid which was released in 2011 demonstrated how an art form at least a millennia old could amaze audiences that had grown up on expensive special effects.

The films of Tony and Iko were two examples of how the fighting arts were still integral to pop culture. This was not a new trend. In the late 19th and early 20th century pop culture would take the regional biases against different fighting forms and the stereotypes about their practitioners and turn them into fodder for stories, comics, movies and eventually video games.

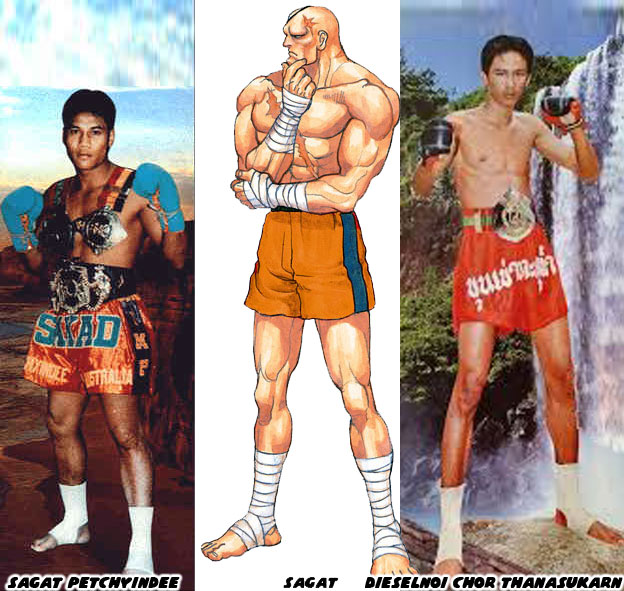

It was not enough for a video game that the Muay Thai master was just an average person. As the final opponent in Street Fighter he had to become much more imposing figure and present a genuine challenge to audiences. The designers at Capcom made the one-eyed fighter into a seven-foot giant. He had a reach advantage, a strength advantage and used a fighting form that was considered more dangerous than karate. The name Sagat was based on Sagat Petchyindee, a Muay Thai fighter that dominated tournaments in the early '80s and undoubtedly made its way into the psyche of the Japanese developers. Although Sagat has always been illustrated as an incredibly muscular man in Street Fighter II he was much lankier. There was another Muay Thai legend that likely inspired this design. Dieselnoi Chor. Thanasukarn was 6' 2", possibly 6' 3" tall, and had a considerable reach and size advantage over most of his opponents. Although he was thin he packed a powerful knee, a "Sky Piercing Knee" according to legend. The character of Sagat was known for his knee strikes as well so it is entirely possible that Dieselnoi had a hand in influencing the developers on Street Fighter. Dieselnoi was such a formidable champion that after several years at the top he was forced into retirement when he could not find an opponent in his same class. Although to be fair Sagat Petchyindee was one of the few to ever defeat Dieselnoi.

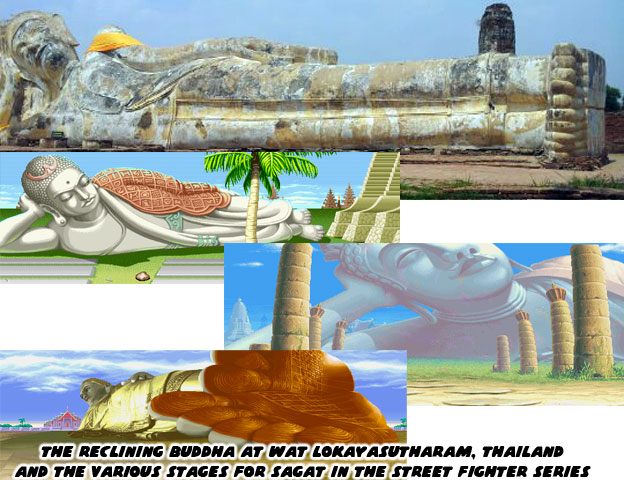

There was something about Thailand that kept designers returning to the region. It was romanticized in comics, its location considered exotic and mysterious to the more industrialized nations in Asia. The inclusion of Hindu temples and Buddhist shrines presented the perfect backdrop for the Street Fighter game series and even the animated films and television shows. Adon, the cocky understudy of Sagat had stages built on the Chaopraya River. The temples of Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom were also used in the backgrounds for Adon's stages as well as the secretive location of the dictatorship Shadowlaw. The reclining Buddha of Wat Lokayasutharam, whose weathered features were awe-inspiring in real life looked fantastic when adapted to the game series.

Ryu was the star of Street Fighter and karate was presented as the ultimate fighting art but the genre would never have been the same without the inclusion of Muay Thai. This survey of the real world fighting forms will take a closer look at the Muay Thai heroes and villains from gaming in the next blog. As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment