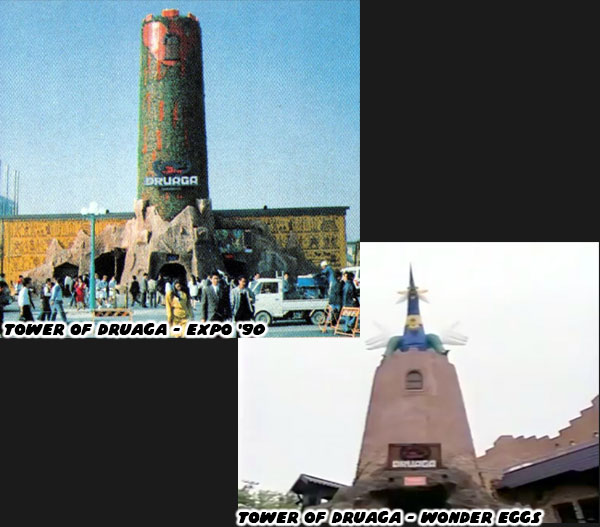

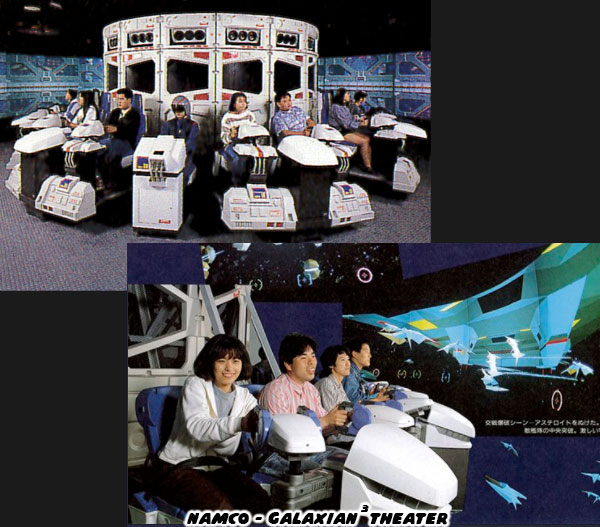

The bookkeepers at Namco were not thrilled that so many resources had been put into Expo ’90. No matter how much money visitors spent at the midway, or how they reacted to Galaxian³, or the Tower of Druaga active simulators, they saw little value in creating temporary rides for the World’s Expo. They asked Shigeki Toyama, and the other designers at the company to never spend that much money creating one-off attractions ever again. I think their showing had the opposite effect on the team, and especially the president of the company. After all it was putting their chips into play that shaped Namco. The founder, and President Masaya Nakamura believed in the power of play. He created a business that ran contrary to what other Japanese studios were doing at the time. He didn’t want to pursue what other corporations were doing, and just stick with manufacturing like his father before. Instead of hiring the top graduates at local universities Mr. Nakamura was hiring creative thinkers, artists, and composers that had no formal gaming education.

Mr. Nakamura's company found the right roles for them. They learned as they went along, created their own tools when none existed, and found new ways to create play. Mr. Nakamura used their contrasting personalities to create hit, after hit in the arcade. It was not unlike the way Walt Disney used the contrasting personalities of his “

Nine Old Men” (who didn’t always get along) to revolutionize animation, live action film, and theme park design.

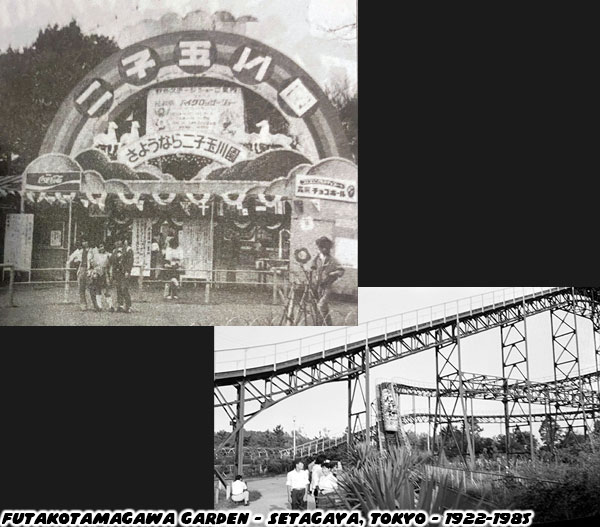

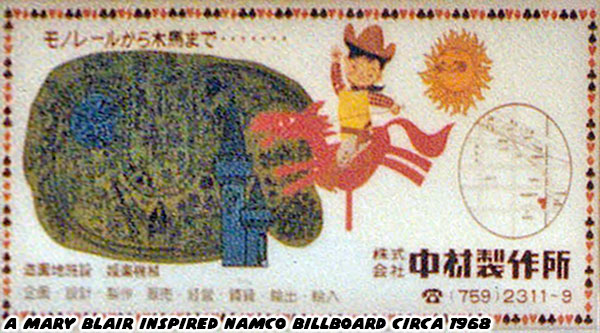

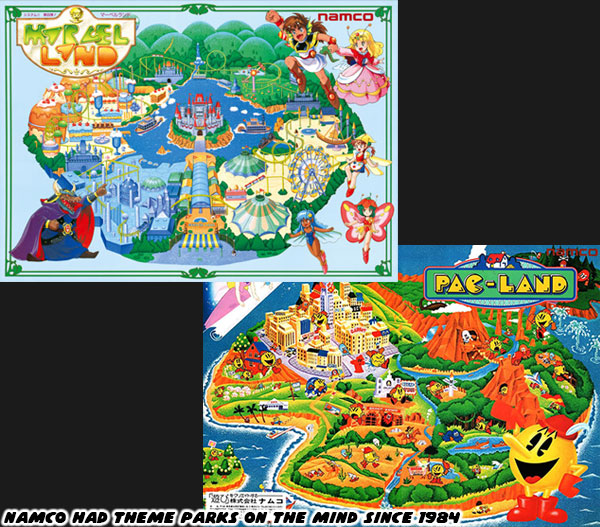

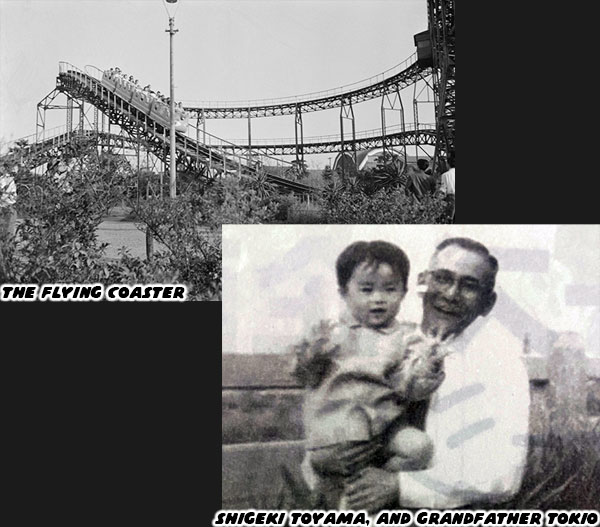

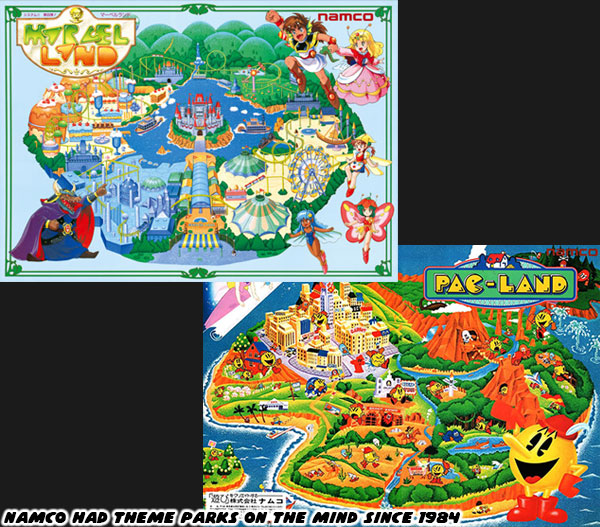

Namco was founded by selling small kiddie rides to malls in 1955. That was the same year that Disneyland opened its doors. It didn’t take long for Namco to move from single person rides, to running entire amusement parks on the roofs of Japanese department stores. It wasn’t just a handful of locations, but instead in every major city in Japan. This lead to them developing their own ride technology, robots, and animatronics as well. When it came to entertainment Mr. Nakamura knew that it was going to become a major part of the Japanese, and global economy. He saw the importance of investing in R&D at every chance.

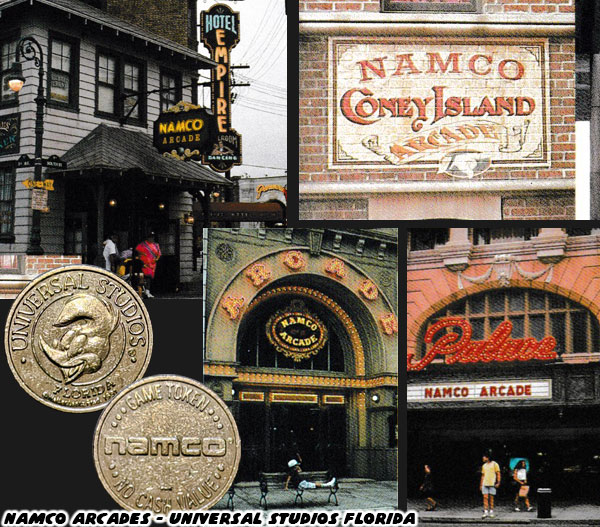

Namco launched a robotics department, whose mandate was on entertainment rather than manufacturing. This sounded absurd to any Japanese business. Automation was already revolutionizing the auto industry. Robots were predicted to take over all of the jobs in the next few decades, and Namco was making them play music, and do dances. The company was among the first to make the leap from electromechanical to video games. The entire time he, and his team were aware of the lessons the Walt Disney Company was teaching the industry. They were fans of the things coming from the west. They were finding out ways to make the art, design, and approach from Disney work for Japanese audiences. One of the things they did was heavily theme their own arcades. They wanted guests to be completely immersed in a world of play that they created. That was especially true with

the Milaiya arcade, and its anime spaceship design.

The ability to synthesize, and remix western culture with a unique Japanese aesthetic was one of Namco’s strengths. They were able to create titles, and especially art that worked in just about any market. Yet it wasn’t the only thing that the company was working towards that would be universally appealing. Everything they did was in service of play. The company did not want to get stuck repeating themselves. They had seen how Atari, Kee Games, and other studios in the USA rose, and fell because they stopped innovating. They did everything they could to push the concept of play forward. For example every space game from Namco broke new ground. Namco’s first big hit Galaxian was a superior version of Taito’s Space Invaders, but they knew that a follow-up had to go in a different direction. They would add scrolling to space adventures in

Xevious, and later build a 3D masterpiece with

Starblade. The alien action game

Baraduke predated Nintendo’s classic Metroid. Even the tank combat

game Grobda was a revolutionary sci-fi title that remixed the Atari mechanics found in Missile Command, and Combat. Best of all the Namco hits were set within a shared UGSF continuity. The studio built a brand that audiences could become familiar with on every new release.

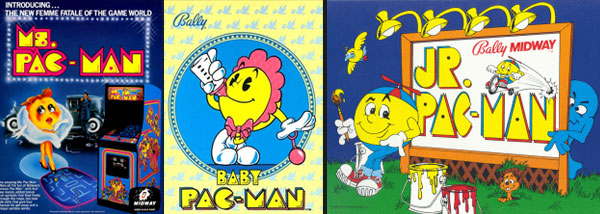

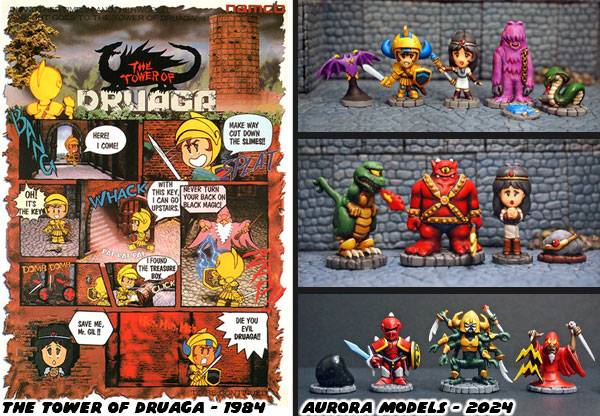

In addition to innovating rides, video games, and robotics the studio was very smart with their IP. Instead of selling games to the international market, they licensed the IP, and allowed games, and merchandise to be produced locally. The royalties they collected helped the company grow rapidly. Unfortunately they didn’t learn that it was bad to remake the same game over and over. Pac-Man (1980) was their biggest star, and highest-earning character. He launched the maze game revolution. Any other company would have been quick to bring sequels to market. Namco tried it, and their sequel flopped with audiences. International players didn’t quite understand the rules, or mechanics behind Super Pac-Man (1982). Collecting keys, flipping cards, and more with two versions of the titular character didn’t seem as intuitive as the first game.

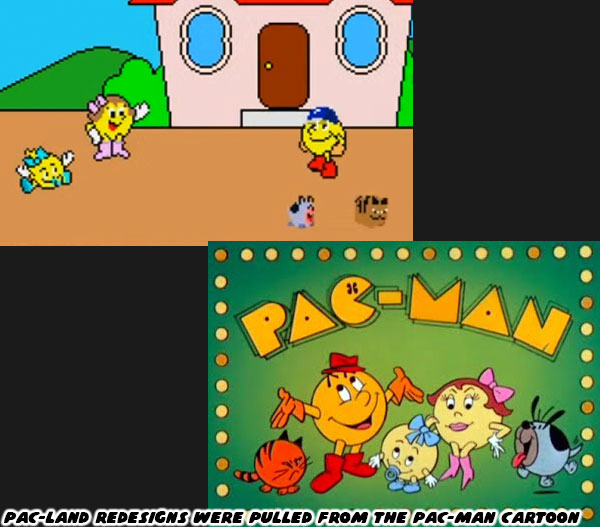

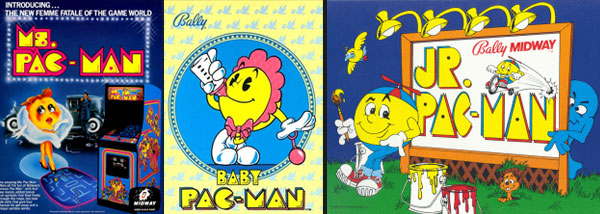

Namco went back to the drawing board. The Pac team needed to figure out what else they could do with the character before he fell out of favor with the public. They saw how popular he was in the US, and how outside companies were making variations of the original, but with the members of his family. A number of the popular “sequels” that you might remember were not designed by Namco at all. Ms. Pac-Man (1982), and Junior Pac-Man (1983) were designed by General Computer Corporation. Baby Pac-Man (1982) was designed by Midway. It could be argued that Namco didn’t even consider that a video game mascot could have a family until the IP was licensed to the US. In the west Pac-Man had a family, and they were featured in the Hanna-Barbera Saturday morning cartoon series.

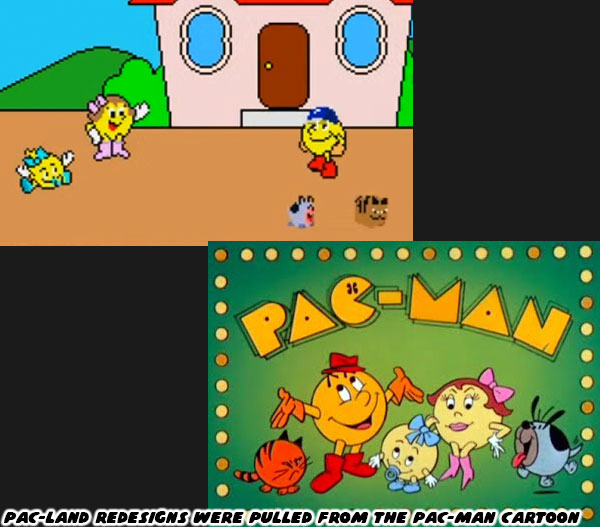

Namco would learn some of the nuances of localization. The version of Pac-Man in the cartoon looked slightly different from the version on the original Japanese marquee art. He wore a fedora, his nose was shorter, he had white eyes, and black pupils like classic US cartoon characters rather than anime designs. Namco wanted to take their version in a bold new direction after the failure of Super Pac-Man. Perhaps he should go on some sort of adventure? His town would be the backdrop for a platform game. The studio would make sure to create sprites that were slightly different for US, and Japanese audiences. This was how Pac-Land came to be, one of the first platform hits from 1984. From that point on the designers at Namco made sure to sprinkle in relationships between the main characters of their various titles.

For example Taizo Hori, the star of Dig Dug (1982), was the husband of Masuyo “Kissy” Toby, the hero of Baraduke (1985). They would have a few kids, and one of the more famous was Susumu Hori aka Mr. Driller (1999). This tradition would help their IP grow organically in comics, and cartoons not unlike Disney through their comics, and cartoons as well.

Pac-Land was created by Namco Research and Development 1 programmer Yoshihiro Kishimoto. His job was to make an arcade game based on the American Pac-Man cartoon. The characters were no longer yellow circles on the screen, but rather large sprites with arms, and legs just like in the show. The backgrounds were made to be vibrant and colorful.

The music was composed by Yuriko Keino, and she was able to create variations of the catchy cartoon theme despite memory restrictions. Pac-Man was no longer stuck in a single screen maze but could instead travel to a destination across a long course. It was considered an important milestone in the platform genre. It set the stage for Capcom’s Ghosts'n Goblins (1985), Sega’s Alex Kidd (1986), and Wonder Boy (1986). Pac-Man creator Toru Iwatani called it his favorite Pac-Man sequel for its interesting concept and gameplay. He said Shigeru Miyamoto told him it had a profound influence on the creation of Super Mario Bros (1985). Miyamoto said that while he was in Tokyo he saw Namco had developed a platforming game he decided that he should follow suit. The only feature of Pac-Land Miyamoto cited as a direct inspiration was the blue background of the game as opposed to the black skies he typically would put in his games like Donkey Kong and the original Mario Bros.

Instead of a joystick the game used buttons to control the left, right, and jump actions. The reason the studio did this was because

Konami’s Track and Field from the year before was a breakout hit. They decided to make Pac-Man control through button presses as well. Many arcade visitors, myself included, didn’t care much for it. I wished that his first platform game had a joystick instead. Pac-Land was not only a response to the popularity of the US cartoon series, but also a way for Namco to share their affinity for all things Disney. The plot of the game involved Pac-Man taking some fairies that were lost all the way back to Fairyland, which was on the opposite side of Pac-Land. These characters had never been featured in the cartoons (to the best of my recollection). The fairies were inspired by Tinker Bell, as well as the Blue Fairy from the film Pinocchio. They were closely associated with the Disney brand, and specifically theme parks. The studio didn’t have to change the fedora from the US version, but they needed something that Japanese players could identify. This detail could help tie their mascot in a fantasy setting. I would argue that the feathered cap in the Japanese release was based on the Peter Pan cap sold at Disneyland, and specifically Tokyo Disneyland. Each of the areas in the game had distinct environments, or themed lands if you will.

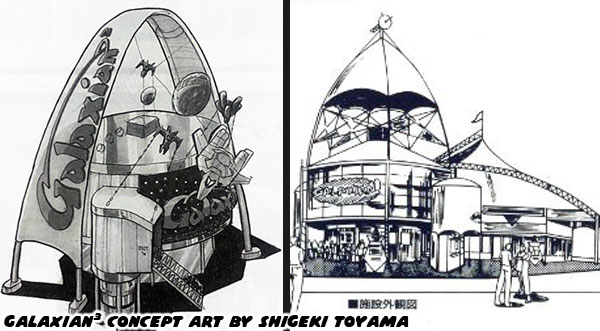

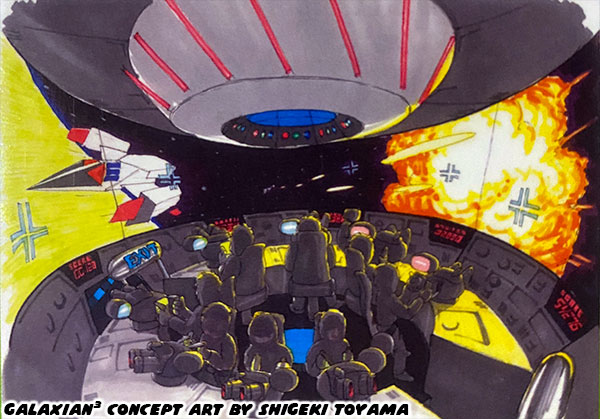

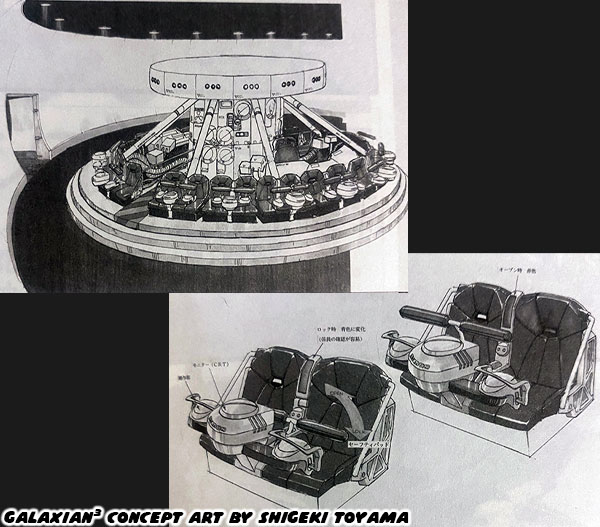

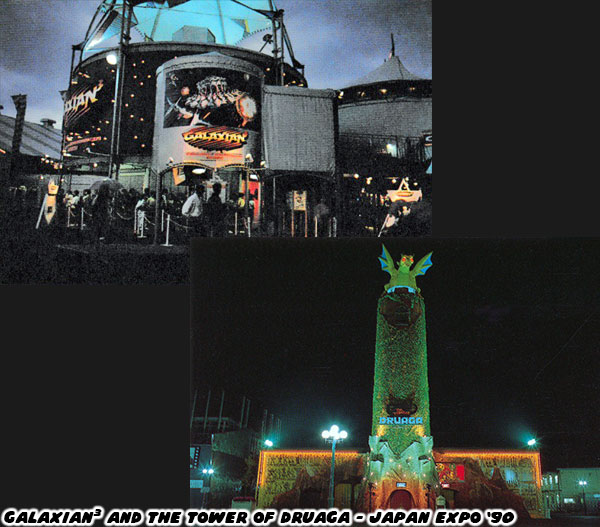

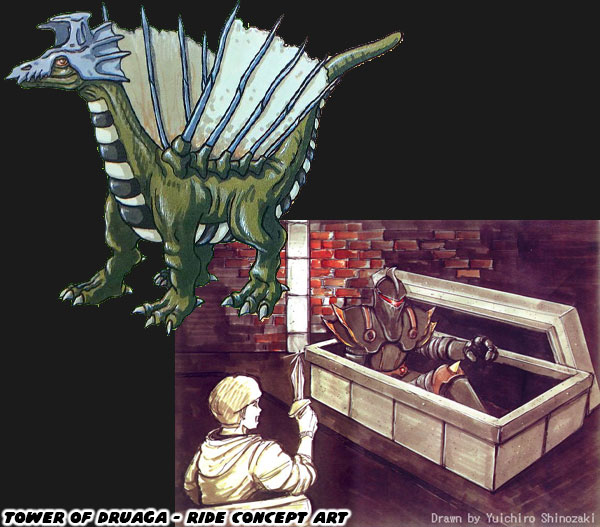

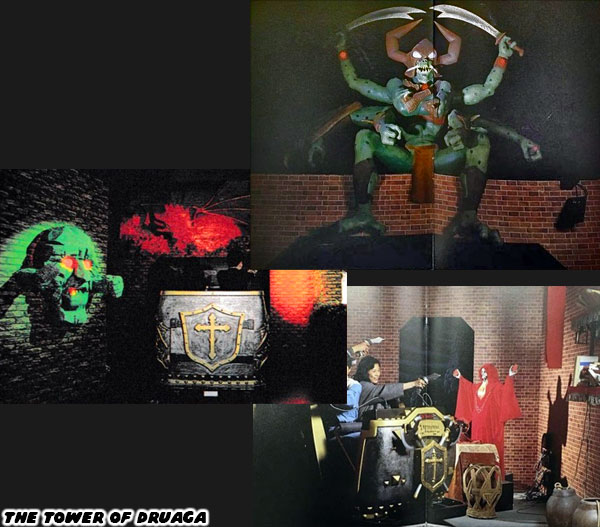

Namco was approaching 35 years in business when they introduced a hybrid amusement ride, and video game which they called Hyper Entertainment. The technology for the Tower of Druaga, and Galaxian³ would debut in the 1990 Flower Expo in Osaka. Namco could tell where the entertainment industry was headed decades before any other company. They accomplished this because they mirrored the rise of Disney Studios. Namco had a leader that saw things that none of his business contemporaries could. He took chances in an industry that was either young, or yet to live up to its potential. He surrounded himself with creative minds that were able to make the impossible happen. Walt Disney did the same thing for film, and animation. He also surrounded himself with brilliant minds. They created an entertainment revolution. Eventually leading to the birth of theme parks.

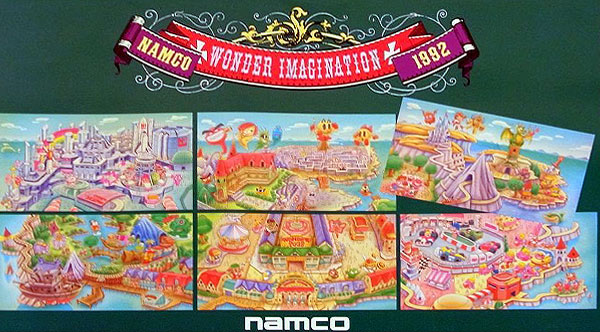

At every instance Walt knew the power of storytelling as a form of entertainment. It was the backbone of most of his greatest works. By comparison Masaya Nakamura the founder of Namco focused on play. The importance of play shaped the creation of their kiddy rides, electromechanical games, video games, and eventually simulator attractions. The pursuit of play, and different forms of play inspired some of the best creative minds in his studio to build entirely new avenues of entertainment. The clues for where Namco was headed were sprinkled through every game, arcade, and concept illustration in the ‘80s. As technology grew so did the ability to create titles with bigger, more complex, and immersive worlds. The studio was putting us in the ancient past, on alien planets, the Wild West, high fantasy, a coaster kingdom, and eventually virtual theme parks in their various games. The titles were wrapped in arcade cabinets that were becoming bigger, and better themed as well. Eventually some of their best arcade titles were simulation experiences.

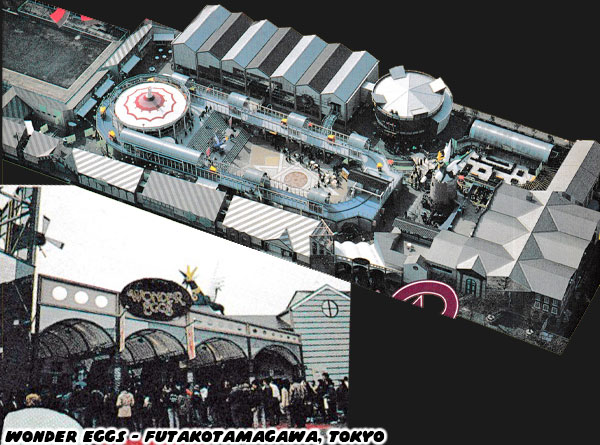

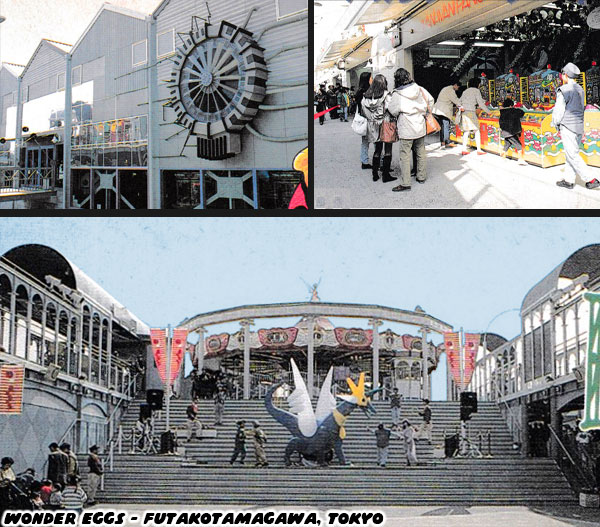

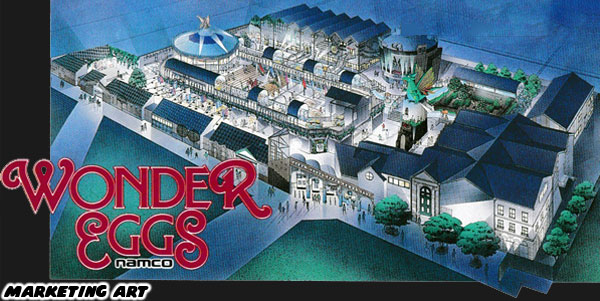

The question was whether they could be able to do these themed titles on a larger scale. After two successive Worlds Expo showings Namco was ready to commit to the next evolution in play. They would create a fully-realized video game theme park. They accomplished this by doing a lot of homework, pursuing revolutionary design, and a little bit of magic. We will start a deep dive in the next blog. Until then I would like to know if you were a fan of the Pac-Man titles, or any of the older Namco titles. Did you have a favorite Pac sequel? Please tell me about it in the comments section. As always if you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

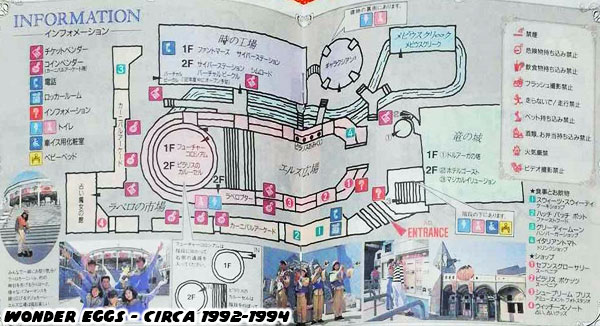

Wonder Eggs, and Egg Empire research collected from: Wonder Eggs Guide Map, Namco Graffiti magazine, the book “All About Namco II", NOURS magazine, The Namco Museum, Namco Wiki, Ge-Yume Area 51 Shigeki Toyama Collection, mcSister magazine, first person attraction details from Yoshiki. Event details from Hole in the Socks