Reminiscing about Star Blade the other day made me think about other games in the genre, not solely the space shooters, but the arcade games that made an impact and were truly memorable experiences. When I was going through my notes on Star Blade I thought about what element the best arcade shooters had in common. Then I thought about what console games provided an equally memorable experience. What did these games have in common? What did they offer that was unique among them? Which were the groundbreaking titles and which were the trendsetters? How did the arcade innovate when home consoles were catching up in the graphics department?

Games became more robust and visually stimulating as arcade technology found its way home in the guise of processors used in PC's and consoles. Silpheed would actually enjoy a revival of sorts exploiting the processing power of 16-bit engines and the amazing storage capacity of CD's. Silpheed for the Sega CD and add-on to the Genesis, was released in 1993. The game was a SHMUP that rivaled the best of the early polygon titles in the arcade. The graphics were cutting edge and lauded for the diversity of locations and difficulty factor. The game was so well made that it could have been considered a contemporary title to Star Blade.

One of the interesting things about Star Fox was that it combined the polygons with sprites on the graphics engine. Nintendo did not rely exclusively on polygons to create the game. Sprites, or raster art made up images for the game characters as well as some of the background graphics as well. The use of sprites allowed the game to have certain color and effects, like an atmosphere on an alien world or cannonballs heading right towards the player. Silpheed featured similar techniques for backgrounds. These visuals could not have been achieved by relying exclusively on polygon technology.

The polygons remained blocky but scaled slightly better than in previous titles. Through the mid 1980's and into the early 1990's this technique was employed to create the illusion of 3D objects on 2D engines.

The thing that all of the aforementioned games shared in common was the gameplay. All of the titles, whether they were set in space, on the ground or in the air, or whether they were in first-person, top-down or third person perspective used a similar game technique. The games advanced on a pre-determined path. They gave players the illusion of freedom, allowing them to move almost any direction across the screen. By allowing gamers the slightest bit of freedom the developers could create the illusion that they were actually traveling to exotic locations. Gamers could enjoy the virtual landscapes that they were taken through without having to actually pilot themselves there.

Just a short year later Sega and Namco would be working almost exclusively on polygon titles. Sega's first foray into a polygon light gun game was Virtua Cop, released in 1994 and Namco's was Time Crisis, released in 1995. Both games used the shooter on rails formula, only that a handheld light gun was used to target enemies rather than a space ship. Light gun games have an equally long and storied history in the arcade but I will not be spending too much time talking about that genre here. I would like to emphasize however the idea that the light gun arcade shooter helped shape the dramatic scope and scale covered in the rail shooter.

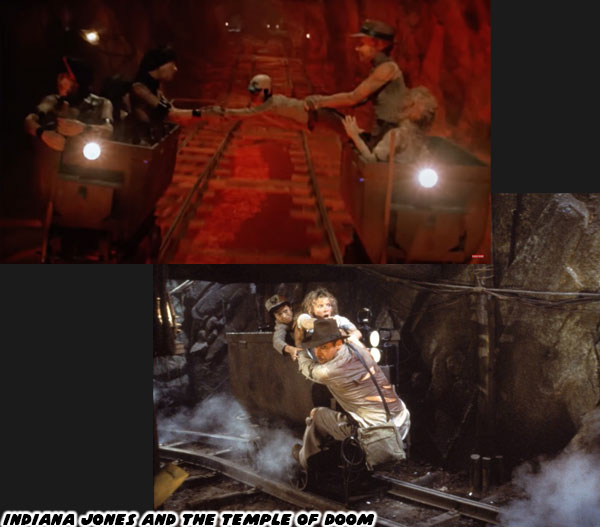

In 1995 Sega created Rail Chase 2. This time the scalable pixels were completely replaced by polygons. The hydraulic seats returned, pitching gamers side to side and tilting them in all sorts of directions as the mine cart found itself perpetually rolling through obstacles. The levels were lavishly themed environments created with plenty of imagination.

The term rail shooter could never seem more appropriate than with the Rail Chase series. Sega did not limit the genre by keeping the entire game on railroad tracks. The mine cart often found itself being thrown down chutes, bouncing through caves, floating down rivers and even sliding over frozen lakes. It had become the perfect, if improbable, vehicle. Sega had a luxury that could never be afforded any theme park. They had created an interactive experience with motion through a series of scenarios, boss battles and locations that did not require the construction of multi-million dollar attractions. They could even broaden the experience by creating alternate paths that players could take just by shooting a switch. This increased the replay value among gamers and gave arcade owners a reason to celebrate. What the genre had needed previously was an engine capable of rendering 3D visuals to go along with the moving seats. The new polygon powerhouses did just that.

Sega continued to push the limits of arcade cabinet design along with the advances in graphics technologies. Force feedback had made game control more interactive. Started with racing games and then applied to flight sims, force feedback controls helped create a new dimension of immersion for players as well. Past a certain point the games were becoming less arcade experiences and more amusement park ones. Seats that moved and rumbled were the start for Sega, with the culmination of movement technology appearing in the R-360. The cabinet allowed a full 360 degrees of movement and could even rotate the player on multiple axis, completely flipping them upside down if they wanted to. Due to size and cost restrictions very few players actually got a chance to see, let alone try the flight sims G-LOC and After Burner on this cabinet. Sega was not deterred from turning their games into more interactive experiences through experimentation. They could achieve a memorable experience with creative level design and by exploring rich themes on every subsequent title.

The last generation of sprite-based rail shooters allowed for some very detailed graphics. Near the end of sprite-based development the engines could support large sprites with hundreds of colors on the figures. When they scaled in size the pixelation was negligible. A few years after the first Jurassic Park game, and following on the footsteps of Rail Chase 2, Sega revisited the franchise with the Lost World. The sprite-based dinosaurs and island were replaced with polygon models. The new dinosaurs were more detailed that even the last generation and the experience was far more intense to players. To increase the reaction among players Sega had created a deluxe cabinet that shrouded the players inside a canopy, making them feel more isolated on the island. Add in seats that vibrated and a loud surround sound system and the experience was as memorable as any motion arcade title that Sega had worked on. This game from 1997 was so well produced it could still be found in arcades, movie theaters and restaurants more than a decade later.

Rolling back the clock a few years we would see that the development of rail shooters from Sega extended to home consoles. We shall explore these titles and connect them back to the arcade in the next blog. If you had a favorite rail shooter, or remember any of the titles mentioned above then I'd like to know about it. Let me know in the comments section please. As always if you would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment