Zeku on the other hand was visually very unique, he had one foot in classical ninjitsu and one foot in the modern world. He wore designer suits yet could change into his fighting uniform in a flash. Zeku was created as the mentor to Guy, the ninja featured in Final Fight, a 1989 arcade hit. I had mentioned previously on this blog how the design of Zeku, credited to senior Capcom artist Bengus, was a nod to the anime heroes from the 1970's. His appearance, his style and even his aesthetic were rooted in the heroes that the Capcom creators had grown up with. But there was another layer of design and meaning with Zeku and with Guy. These were the templates that created the character Strider, a hero from a 1989 arcade hit of the same name. Strider was a revolutionary title. I can say with fair certainty that there was no game that looked even remotely close to it. Part of the reason for its unique look was because people outside of Capcom, a manga collective known as Moto Kikau established the world of Strider Hiryu. They set him and his organization up against a terrorist organization made up of martial artists, robots and cyborgs, lead by a shadowy villain known only as the Grandmaster.

Strider was a cult-hit in the arcade and a smash on the consoles. It was one of the first arcade-perfect games to appear on the 16-bit Sega Genesis in 1990. The 8-bit Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) also had its own version of Strider. It came out a few months after the arcade game but was graphically inferior. The main character was the same, he still used a sword called the Cypher, fought bosses and traveled the globe. But because of the limited resources on the NES they had to focus less on graphics and expand on the game play. The stages were laid out more like you would expect on an 8-bit platform game, something like Contra or Rygar. Despite the small sprites and limited animations it was still a fun game to play. A big plus was that the story was expanded. It was much closer in details to the manga. Capcom had a lot of buzz from the community but didn't really capitalize on the game right away. A third-party developer, Tiertex Design Studios, made a sequel called Strider II aka Journey from Darkness: Strider Returns. The game was released on the PC and a few console systems but was lackluster in every regard. It rehashed the sprites from the Genesis game and did little to expand on the game play. An actual Strider 2 by Capcom would not debut until 2000. The new game was designed for the Sony Playstation. It was a mix of sprite and 3D backgrounds, making it one of the earliest 2.5D games ever created.

Strider had an iconic design. His costume was a blend of cyber-futuristic with classic touches. His costume down to his split-toe boots were something that you might have seen in a traditional manga or anime. Inspired by actual fighting uniforms it was blue rather than black. It turns out that for an assassin a dark color was easier to camouflage at night than absolute black. The costume was also functional, in that it allowed him a full range of motion. His character was about speed and stealth, these are things that would have been sacrificed with heavy armor, like that of a samurai. The biggest update to his design was the sword. It was replaced with a Cypher, a stealthy weapon he could strap to his back that functioned somewhere in between a lightsaber and a tonfa. Strider Hiryu was dangerous because of his fighting ability and his blinding speed. The high tech gadgets at his disposal were the frosting on the cake.

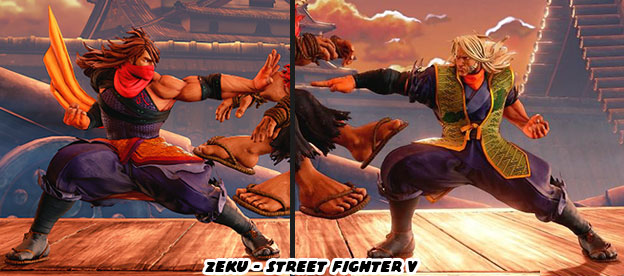

When we look at Zeku we are meant to think about Strider Hiryu. Obviously because his alternate costume is in-line with the other Strider uniforms. But we are also supposed to think of Strider because of the array of quick strikes and amazing acrobatics. Lightning speed is something that works extremely well for Ibuki in Street Fighter III (SF III) and Guy in Street Fighter Zero / Alpha (SFZ). The diversity of physical attributes and fighting styles is something that Street Fighter became known for. No matter how broad the size differences were the studio made an effort to keep the game balanced. The massive Hugo and tiny Ibuki were evenly matched in SF III because it was a contest of power versus speed. If a player had great technique then they could use either character well in the game. Yet where did this style of character come from? How did the Strider-like fighter evolve?

One of the early and popular ninja series in the arcade and consoles came from Sega. The Sega arcade game Shinobi from 1987 placed the ninja Joe Musashi in a modern setting, fighting a present-day cartel with his traditional weapons, the shiruken and a kodachi or short sword. However he could also use a handgun if he picked up a power-up. It was an interesting play mechanic, and influential to the development of the action platformer. Musashi was made all the more interesting with his ability to use ninja "magic." These were special attacks that allowed him to clear all of the enemies off of the screen or do tremendous damage to boss characters. Shinobi predated the other arcade hit Ninja Gaiden by a year. The aptly named Team Ninja, a group of developers from Techmo, introduced the world to a new hero. Ryu Hayabusa was their ninja-versus-modern crime lord archetype, the game was closer in game play to Double Dragon than Shinobi. Musashi and Hayabusa were names pulled from Japanese history but their video game personas became the new types of action stars. Each character appeared in a series of games for the consoles and handhelds over the next 20+ years, further expanding on the role of the ninja in pop culture. Shinobi and Ninja Gaiden predated Strider but I would argue that neither really were that influential to Capcom.

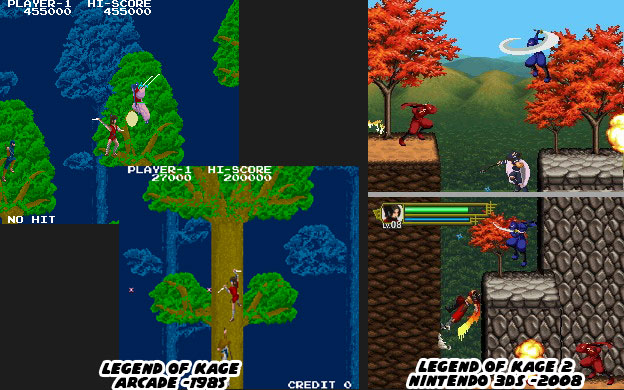

In 1985 (1986 in the US) Taito released Kage no densetsu, better known as the Legend of Kage. It was an action platformer the likes of which had never been seen before. The premise was straightforward, bad guys kidnap a princess and it's up to Kage (Shadow) to kill the bad guys and rescue the girl. The entire game was set centuries ago in Feudal Japan and it featured Kage, a young apprentice from the Iga school. He didn't resemble what we would consider to be a ninja but his clothing was accurate for the era. He fought costumed ninjas as well as other assassins and magic users on his quest. The game was notable because players would fight waves of opponents on a background that allowed players to scroll left, right up and down. Most games back then only advanced in one direction. Moreover the way the player moved and how he fought had never really been done before. Kage was insanely fast and when he jumped he leaped three or more times his height. This allowed him to jump onto tree branches and jump even higher into the canopy until he could fight his opponents above the treeline. These were the types of fights that had been romanticized in manga and cinema.

The game was also very violent for the time. Although there was no blood players could kill opponents with either a shiryuken or with a quick slash from the kodachi. There was none of this knocked out nonsense. Players would leap into the air, throw his stars in any direction while slashing in the opposite direction and any ninja that was in the line of fire would come crashing down head-first. This nonstop killing barrage was the core of every Strider encounter. Players would also block other shiryuken by spinning their blade around. An action video game with both offensive and defensive controls was very rare. The game also changed locations. Players tracked down the clan of the bad guys, through the forest, up a retaining wall and inside a labyrinthine castle where they would find the princess and make a harrowing rooftop getaway. When the intuitive fight and defensive controls were combined with the evolving stage design and non-stop fights it made for a cult hit.

The Legend of Kage was arguably the most influential of the early ninja titles and colored the work of other game and animation studios. Yet even Kage came from somewhere. Ninjas had been a part of Japanese cinema for more than a century. Motion pictures started filming in Japan at the end of the 19th century and started playing at the start of the 20th. The early films were recordings of kabuki theater. Films with a plot came right after, bringing folklore heroes to life. One of the oldest ninja heroes in cinema was Jiraiya (Young Thunder) Gōketsu Monogatari. He appeared as he would have in story traditions, that was he didn't have the typical ninja mask or costume but something closer to everyday wear. He was a master of disguise, wily and charming, with the ability to shape-shift and cast all sorts of magic. He was like WuKong the Monkey King meets Robin Hood with the same amount of cultural significance in each nation. Films on Jiraiya went back to 1914 and turned up again and again over the next century. The way the character moved, his spell casting, his fighting became the standard for over-the-top ninja characters in film, anime and games including Strider and Naruto. In fact Capcom actually tried to make a game on the character post 2000.

Capcom had just released Maximo: Ghosts to Glory, a sort of 3D successor to the classic Ghosts 'n Goblins arcade game. In the original 1985 game a knight in shining armor named Arthur had to save princess Prin-Prin aka Guinevere from a horde of demons. In the updated 2001 game the story was reset to feature Maximo who wore a costume that was more Roman or barbarian in origins. The game was developed by a Western team led by David Siller (Crash Bandicoot / Aero the Acrobat). It was a hit and Capcom wanted to do something similar from a Japanese point of view. Jiraiya Kenzan was an unreleased PS2 game that would have been released in 2002/2003. It featured the art and design of Susumu Matsushita, a Japanese artist who had created thousands of covers for Famitsu magazine and was known for his western-cartoon-style designs. It didn't hurt that he also happened to be the lead artist on Maximo. Sadly there was no Jiraiya game and no telling how it would have compared to Maximo. Would it have been a 3D version of Legend of Kage? Or would it have been more like Ninja Gaiden, Shinobi or Strider in 3D? We'll never know.

There was one person that I felt was overlooked for the evolution of the high-speed ninja gaming archetype. Kouichi Yotsui was the director on Capcom's Strider. He had difficulties working with the company, whether it was management or another senior person was unknown. He was one of the first directors to leave Capcom while it was in its prime. Mr. Yotsui had nothing to do with Strider 2 (2000) or Strider by Double Helix Games in 2014 but you don't appreciate how much his fingerprints were on the original game until you look at the other titles he released. He directed Run Saber for the Super Nintendo. It was developed by Horisoft and published by Atlus in 1993. That game looked and played very much like Strider for the SNES. This was important because Sega had the exclusive rights to a 16-bit console version of Strider. Run Saber expanded on the list of game play mechanics set up by Strider Hiryu. The new characters Allen or Sheena could perform all of the same basic attacks of Hiryu, they could also climb and run just the same. The duo now had a diving kick which allowed them to smash through opponents as they descended. Run Saber was also a multiplayer game, whereas Strider was a single player experience. Years later Mr. Yotsui directed Moon Diver. Developed by freeplus, and published by Square Enix in 2011, the game was another return to the classic Strider feel. It made me realize how little credit the man got when it came to the genre and the type of cinematic action he helped create.

Mr. Yotsui's spiritual successor to Strider was another arcade game named Osman (Cannon-Dancer in Japan), published my Mitchell Corp in 1996. The game was beat-for-beat just like Strider. It was so similar in fact that the stage progression was almost identical. In Strider the setting was a futuristic Soviet Union, in Osman it was a futuristic Persian Gulf. The moves of the main character, Kirin, were identical to Strider Hiryu. He could fight, flip in the air, and climb. The lone assassin was a master of the "Secret Style" which allowed his punches and kicks to be as deadly as Strider's trademark Cypher sword. Kirin also had a new special "Fatal Attack" which was his screen-clearing move. He was on the hunt for Abdulla the Slaver, a female goddess-type character. She was the surrogate to the Grandmaster, the shadowy figure from Strider.

You begin to appreciate Mr. Yotsui's contribution to the genre and specifically the game play from Strider to Zeku when you look at the details in every game he's directed. In both Strider and Osman there was an emphasis on violence. Yes, graphic violence was in the manga, and had been a popular thing to do in post Hokuto No Ken / Fist of the North Star titles. But this was one of the first times graphic violence had been depicted in an arcade game. Strider killed opponents faster than any arcade hero previously. Bodies were getting sliced to pieces, or exploding in grotesque detail, but the sprites flickered so quickly that you couldn't really tell what was happening. Only when you go back and take a close look at the sprites and animations do you appreciate the frenetic deaths that Mr. Yotsui put into the game. In Osman the villains disintegrate in a flash of color and guts as Kirin strikes them down. If Zeku were based closer on the work of Mr. Yotsui then he would have had more lethal strikes. That or he would have been perfect for Mortal Kombat.

Kouchi Yotsui was a pioneer of cinematic action sequences in his games. I don't mean that he wanted to show the action in a CGI cut scene, or with a quick time sequence. Mr. Yotsui wanted players to experience what it would be like to do something incredible in game that would have been a highlight in an action movie. For example Strider ran down the side of a mountain while landmines exploded behind him. He ran faster and faster, gaining momentum then players made a blind leap before the cliff collapsed under them. This would have been an amazing shot in a Jackie Chan or Mission Impossible movie. In Osman a truck was chasing after Kirin down the side of a building. Again the character was running faster and faster until he could leap out of the way and let the truck smash into the roof of another building. These and many more amazing sequences (the gravity room, the airship, the satellite base) were what made the games unique. Nobody before or after Mr. Yotsui had produced games with the same over-the-top feel. He took the movie-style action of Legend of Kage and put it in a science fiction setting. If you play Zeku or are a big fan of the lighting-quick ninja fighters like Strider I want you to remember the work of Mr. Yotsui. He isn't credited as much as he should be and we should change that. As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

What a great text! I'm a fan of your site

ReplyDeleteThank you Lucas!

Delete