Western audiences were quick to point out the characters that the

Xuan Dou Zhi Wang / King of Combat lineup was based on. They would try to shame the Chinese developers by calling out their lack of originality. Yet if they were to look at the history of video games there was often some sort of poaching going on, and certainly some level of cultural appropriation that was never called out. This was especially true in the early days of the industry. Two of the most important games in the evolution of the fighting genre used China as a backdrop. Kung-Fu Master by Data East came out in 1984. The game was inspired by the Bruce Lee film the Game of Death. In the movie Bruce went from floor to floor, moving between harder and harder opponents until he fought the final "boss" at the top floor. Kung-Fu Master incorporated elements from that film as well as other Chinese hero or “wuxia” stories.

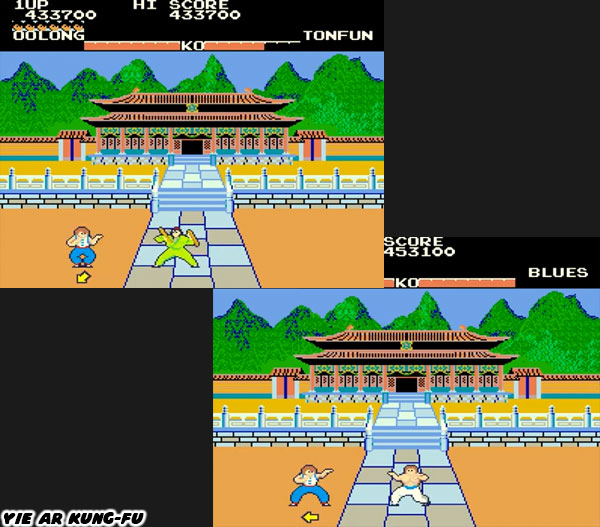

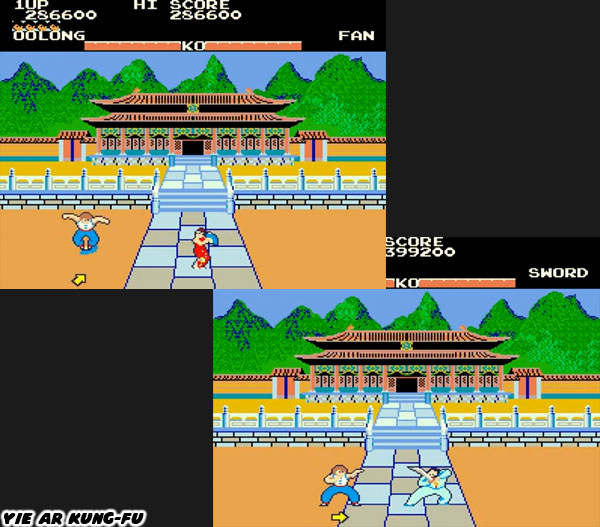

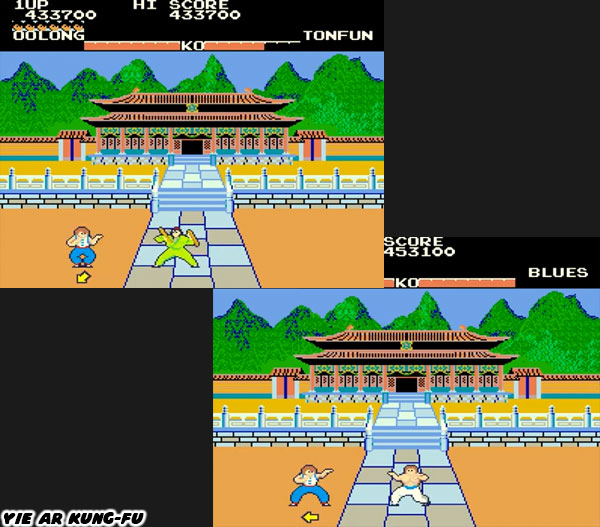

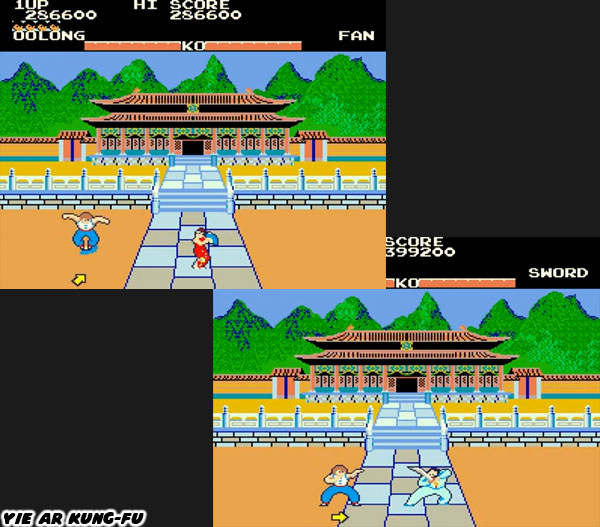

Kung-Fu Master was an important milestone because the evolving enemy types had not been done previously in a fighting game. It was also the basis of the brawler genre, in which one player had to fight off wave after wave of enemies. A year later Konami released a game that was the template that all fighting games would follow, including the original Street Fighter. Yie Ar Kung-Fu featured a Chinese hero named Oolong. He fought masters of different styles, including a few women. Some masters fought with hands and feet while others with a particular weapon. The characters were all grounded in classical styles and looked as if they had been plucked out of Chinese martial arts cinema. Even the backgrounds in the stages looked like traditional watercolor landscape paintings rather than photorealistic images.

The thing to remember was that China and the Chinese martial arts were welcome in video games. They were celebrated for their visual splendor and fancy moves. Fan and Star were featured opponents in Yie Ar Kung-Fu. They were the first female martial arts fighters in a game. They predated the iconic Chinese character Chun-Li by six years. In fact before Capcom even created Chun-Li they had designed a trio of female martial artists that could hold their own against the titular character Strider Hiryu in the arcade game Strider. The Kuniang Martial Arts Team aka The Tong Pooh Three Sisters appeared in 1989. Chun-Li would not appear until 1991. The sisters were fabled bounty hunters, selling their deadly talents to the highest bidder. Their pseudo-traditional Chinese martial arts uniforms beguiled their amazing powers. The sisters could cut tanks in half with their powerful kicks. They were the perfect challenge to the futuristic ninja Hiryu.

Capcom was without a doubt one of my favorite companies growing up. The arcade games the developed had no peer in my book, yet they could also be used as an example of the cultural appropriation that was happening within the gaming industry. Chinese characters in fighting games were often presented in some sort of pre-revolutionary martial arts costume. It didn't matter if the character were appearing in in a current timeline. Chances were they were dressed in the costume that would have been appropriate in the late 19th century rather than casual modern clothing. For example the Three Sisters were presented in costumes that made more sense in the classic Chinese Opera rather than in the science fiction future that Strider was set in. Even Chun-Li was presented in a pseudo-traditional costume in Street Fighter II. Within the context of the game however her costume made sense.

Chun-Li was a police officer that was going undercover into a fighting tournament. She couldn't exactly wear her badge into battle. I described the appeal of Chun-Li in a series called the Female Equation if you haven't read it yet I suggest visiting the link. The most important things that could be learned from Chun-Li were based on her name. She was inspired in part by Wing Chun, the legendary martial artist that had a fighting style named after her. Chun-Li was also inspired by the kicking speed and fearless spirit of Bruce Lee and the characters he played on screen. If you remember the undercover officer that Lee played in Enter the Dragon had also entered a martial arts tournament. Capcom flipped the script by turning Lee into a woman yet maintained her importance in the context of the story.

Chun-Li was not a token hyper-sexualized character nor was she some sort of damsel in distress. She was one of the most carefully planned out and respectable characters in the history of video games. This was something that I had yet to hear Anita Sarkeesian bring up in her game criticisms. The inclusion of Chun-Li was something that the Chinese audiences could be proud of. Through the history of Chinese martial arts cinema there had been formidable female protagonists. Going back to the 1920's strong female characters had always been a part of the movie experience. In other countries women were often the prize for the hero, they were in need of rescue or vindication. That was not always the case in China. Certainly there were revenge stories where women were raped, murdered or kidnapped, but there were also many more films where women were tremendous fighters and leads in the films. In several cases they upstaged the men. Some women played major villains as well adding more weight to their contribution in action cinema. This was something that the Japanese developers had picked up on and made sure to use when introducing Chun-Li and the Three Sisters into gaming history. Sadly the action films from the west rarely used a female lead. Rare was a director like Luc Besson, who knew that women could make for amazing action stars and not just be used as eye candy on the big screen. But I digress. The Japanese studios were becoming hung up on presenting one take of the Chinese in fighting games.

In Capcom's Final Fight, which also debuted before Street Fighter II, the Chinese characters looked very stereotypical. Even when the series moved to the consoles in following years the studio did not try to evolve with the times. They made sure to give the Chinese characters a very particular look. The males had long braided ponytails, wore slippers and had names like Wong Who, Won Won and Wong. I wish I could say that they were based on a particular movie hero or villain but they were instead gross generalizations of Chinese thugs and gangsters. It was an easy tool for the majority to caricature foreigners and immigrants, especially in a nation that had never had a civil rights movement. The characters in many fighting games, not just by Capcom, were skirting the line of racial pandering. This was not limited to the Chinese either. Blacks were by and large known for only a few things according to game culture. They were good at sports and dancing. The two stereotypes were combined when they appeared in a fighting game. I wish there were more positive role models in games like Dudley the boxer but he was few and far between. Instead audiences got

Boggy the Dancing Master, Magic Dunker and a slew of other basketball playing figures.

The Chinese heroes in brawlers and fighting games were again placed in classic costumes. Some wore decorative robes and some looked like Shaolin Monks. Sometimes they appeared like Bruce Lee and fought with nunchakus or costumes that he would have worn in a movie. SNK, Capcom, Data East, Namco and Midway were just some of the many developers in the East and West that relied on trope to design Chinese martial artists. What none of the studios seemed to grasp was the effect that this was having on the Chinese audiences. When it came to fair representation in gaming China wanted to be part of the conversation. They wanted to be seen as more than a costume. After all the majority of martial arts, especially those in Japan were rooted in China. The practitioners in Mainland China may have been strict traditionalists for certain styles but this was not the case for every form of self-defense.

There was a broad diversity of styles that had never been captured accurately in film and especially not in the game screen. These true arts deserved some exposure. Even Chinese-Americans like Bruce Lee were excluded from the conversation. He wanted to adapt the elements that worked from different systems and mix them together into a hybrid form which he called Jeet Kun Do. As much as Lee was imitated by the rest of the world the lessons that he set out to teach were missed by most of the producers. They turned him into a caricature based on his movie roles. He became just like the Chinese practitioners that came before him. He was something that could be synthesized into a few visual cues and put into a fighting game. He went from fighting drug lords and fighting for the respect of Chinese nationals on film to fighting panda bears and robots on the video game screen.

The Chinese were in a conundrum. Those that lived in the country and those that lived in the city were keenly aware of how they were being represented in popular media. The nation had grown tremendously since the Cultural Revolution but you wouldn't know it if you relied on fighting games to give you the news. When the developers at Jade Studio tried to create a fighting game and join the conversation the world saw nothing but the blatant rip-off of the King of Fighters. Those that took a moment to understand the roots of the characters saw something else. The costumes, colors, moves, abilities and even story had a distinct Chinese aesthetic. The developers were keenly aware of what was going on in sports, street culture, music and the martial arts. They knew how all of these elements contributed to pop culture. They knew how these elements should be incorporated into the design of their characters, stages and gameplay. In short they knew how to make the game into something their own. Certainly the characters had a familiar KOF design to them but I would challenge critics to look a little closer. The stylization of the characters was more manhua (Chinese comic book) than manga.

The diversity of the characters was also more inclusive of people of color than most KOF or Street Fighter titles. Characters could have dark skin, light skin and still be Chinese. They weren’t simply given a basketball or shown to be some sort of b-boy (break dancer). The racial gimmicks were left on the sidelines. When was the last time a mixed ethnicity character was featured in a fighting game? When was the last time a minority was shown without some sort of cultural trope? Imitation was the biggest sticking point for the community but sometimes the community missed how much imitation helped the industry grow. We will visit this idea in the next blog.

If you would like to sponsor me

please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment