Auto Modellista, a console title game from 2002 was an attempt for Capcom to get a franchise racing game established. The studio was better known for their fighting and adventure titles more than their racing games. Their previous high-profile title MotoGP was actually started by Polyphony Studios, the people that created the Gran Turismo series for Sony. Before that Capcom had not made a serious effort to get a racing game in their library since Slipstream, an arcade racing game from 1995. At that time Capcom was a little late in trying to jump on the racing bandwagon. Slipstream used pixels instead of polygons for their graphics engine. By 1995 the two major arcade racing developers Namco and Sega had long since moved away from sprites to 3D textured polygon models. Slipstream looked like a better version of Namco's Final Lap, the 1987 spiritual successor to Pole Position 2. By 1994 Namco had released the all-polygon Ace Driver a year before Slipstream. Although crude when compared to modern 3D racing games it was years ahead of the technology used by Capcom.

Racing leagues including Formula-1, NASCAR and GT had already been done by other publishers. Genres like kart racing, rally racing, boat racing, monster truck racing, combat racing and even science fiction racing had also been explored on various consoles as well. Capcom would have to come up with something unique to stand out from the glut of racing games on the market. The wanted to have several things that no other racing game offered, the defining feature would be the graphics. The game used cel-shading to help give the cars an animé quality. Not many games have been released using the graphics technique and very few of them, like the 2001 arcade sleeper Wild Riders were racers.

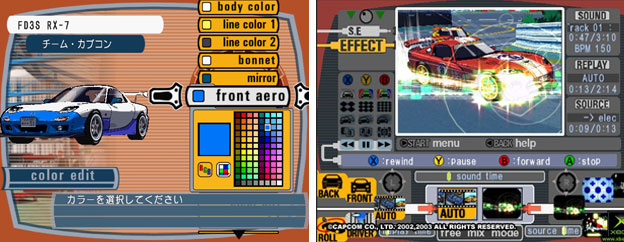

By going with cel-shading Capcom was able to make great use of lighting, shadows, colors and even textures on the track. The high contrast between the cars and environments made for a game which looked good from every angle. Small details like the brakes heating up and changing color could be made out behind the spinning wheels. The engine even rendered "speed lines" like an illustrator would to convey movement on the edges of the frame while players raced. The faster they went the more speed lines they would get. To put it succinctly no other console racer looked like Auto Modellista.

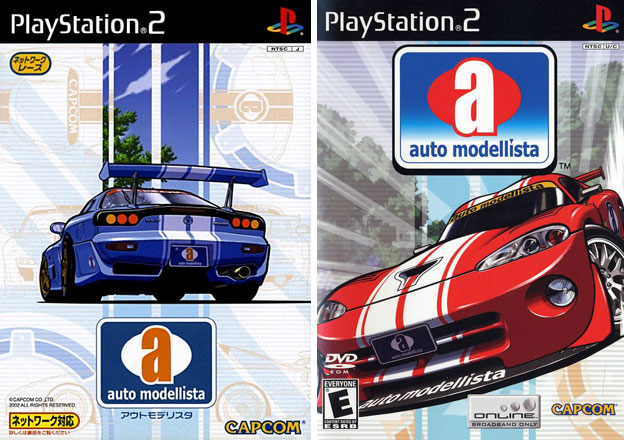

The cars featured in the game were licensed from real world rides. Most of the major manufacturers from Japan and the US were represented. The game did not have the hundreds of makes and models from a title like Gran Turismo, instead it focused on the sportier cars from the major companies. In Japan the legendary street racer the Mazda RX-7 was the poster child for the game. In the US it was the Dodge Viper. The game actually had a couple of releases in Japan because not all the licensed cars were in the original release. After the US and UK got their versions with a few more rides then Japan got the full version with online support. The game was one of the rare PS2 racing games that supported 8-player online play. Some bundles in Japan included a special network adaptor for the PS2 to try to get more players interested in the release.

There were only a handful of courses in the game but they were all based on real Japanese locations. There were several mountain stages from rural areas and big city circuits. The Suzuka raceway was the most high-profile track in the game. The city circuit tracks were set at night and offered players a chance to drive the circuits in the rain. This meant carefully tuning each car for maximum efficiency and changing the tires from racing slicks to radials. There was a bonus track for players that completed all of the challenges. The Tamiya Kakegawa Circuit was the site of many remote control car racing championships. Once a player had unlocked this track then they could take any car to it. The car would be miniaturized and made to look and sound like an actual R/C car. Players could see the pins holding down the body kit as well as the antenna sticking out of the frame. Even the sound of a tiny electric motor would replace the usual engine sounds. It was a treat watching the world pass by from the POV of a toy on the road.

To make the game even more unique it offered players the chance to personalize cars in the Garage Life mode. The body kits, tires and aftermarket parts were all licensed from real companies. Players could not only assemble their ideal rides, they could also tune it up, paint it and even cover it in real or created stickers if they wanted to. To help further set this game apart from the other racers on the market there was a Video Mode as well. Before Auto Modellista there had been games that allowed players to save and edit replays of races. Auto Modellista allowed players to add music, filters and video effects in addition to the usual editing tools. Players could make replays that were as dazzling as music videos and save them to their memory cards.

The music featured in the game was composed by Tetsuya Shibata and Isao Abe. It was an eclectic mix of jazz, electronica and trip-hop that did not rely on any licensed music. Some people would argue that the music was actually the best part of the game. The two-disk soundtrack is actually one of the rarer Capcom albums sought by collectors.

The game had a distinct visual look, a great soundtrack, a decent lineup of cars, customization and online support but it was missing something very important. It lacked solid control, the most crucial element to any game. The cars did not handle realistically, nor did they handle in an exaggerated arcade style. For a game that featured numerous mountain stages the absence of drifting or sliding the cars around corners was shocking. It was seemingly impossible to get the cars to even commit to a slide. Players could choose the most powerful car in the game, give it slick tires and put it on a rainy track and it would still not drift more than 10 feet without coming to a screeching halt. Even the R/C cars that players could race on the Kakegawa circuit did not respond realistically. A remote control car raced and handled much differently than a real world car. At scale the small cars could go over 300MPH and hug turns impossibly close to the edge without losing control. Conversely if the driver wanted to have a drift race with an R/C car then they could also make the small cars race completely sideways at command. That lack of detail for the real and R/C physics broke a game that was filled with tremendous possibilities as much as it was filled with style.

Perhaps it was the focus on style rather than substance that ultimately lead to the game being panned by critics and players alike. The courses were well done but players were expecting more locations. Instead Capcom offered an uphill and downhill version of the two mountain stages and a clockwise and counter-clockwise version of the city circuits. The great visuals exploited on each track were done in by the lack of diversity. The novelty of the graphics wore off once players had mastered the tracks. There was little else to do than play dress-up with the cars a player had unlocked. Perhaps this was the greatest strength that the game had overlooked by most players and editors.

Auto Modellista means car designer in Italian. It does not mean racing simulator. The focus on the game was more on the look and design of the cars rather than racing. It never aspired to be taken as seriously as Gran Turismo. The game was designed to make car enthusiasts slow down and appreciate the cars and car culture. If ever there was a videogame that required players to approach it differently than other titles in the same genre then this was it. I would compare the experience of Auto Modellista to the Japanese concepts of food preparation and presentation.

The nation of Japan was known for their elaborate tea ceremonies however they were also known for creating sophisticated but inexpensive box lunches. The bento box put different but complimentary food choices into small compartments. By doing so none of the flavors would cross contaminate the others. This also allowed crisp food and moist food from spoiling each other. The bento boxes and ekiben or bento boxes for train commuters evolved to include a number of unique food combinations that would stay fresh for travelers. Some of the boxes, especially the ceramic kind were designed to be saved, collected and reused. Even the plastic boxes were designed with some forethought. They were sometimes decorated with sumi, or ink wash style paintings. Those that slowed down from their busy schedule to enjoy each meal appreciated the flavor combinations and even the preparation that went behind the meal. Every facet of Auto Modellista was compartmentalized and meant to be savored individually. The unlocking of cars and tracks. The customization of the tires, engine, suspension and body. The ability to paint and cover the car with sponsor stickers. The ability to remix race videos. All of these things were well done individual components. The whole could then be appreciated especially when compared to the other racing games on the market.

Garage Life Mode was used to hold the attention of players and help them acknowledge the differences in the title. Gamers could choose from three types of garage, the racing, contemporary and tudor styles. Each garage could then be decorated with items collected by winning races. Trophies and plaques were the obvious choices to hang on walls but beyond that players could set up their space any way they wanted to. They could put down and organize cabinets, tool boxes and machine parts. Players could unlock vintage tin signs, old cans of oil and antique radios to put on shelves. Posters from real world locations and billboards could be hung along the walls. Even the Servbots from Mega Man Legends could be displayed as trophies. Layer after layer could be built up in each garage. The items placed and displayed would tell something about the racing fan as much as the car featured in the room. It was very much like assembling a bento box suited to the tastes of the gamer. The minutiae provided by Auto Modellista were often overlooked in other racing games. Players rarely, if ever, had the time to spend simply appreciating the cars they had unlocked. Assembling a virtual collection of car memorabilia was unheard of, as was making music videos out of saved races.

The majority of the cars in the game were fairly well known to car circles; the Corvette, Mustang, Cobra, RX-7, 350Z and even Skyline had great racing reputations. Some of the other choices for the game had never been featured in a racing game. The Jiotto Caspita by Dome Co. was a very rare Japanese exotic car that could actually give the other supercars in the game a genuine challenge yet was virtually unknown to most gamers. The other, the Orochi by Mitsuoka was described by the hosts of the British show Top Gear as the ugliest car ever made. I think the Top Gear commentators were a bit full of themselves when they came to that conclusion. The lines and styling on the Orochi were very bold, as bold as those from the Italian Ferrari or Maserati designers. To me the car looked aggressive and even threatening. If it were not the perfect Interceptor from the game Spy Hunter brought to life then I wouldn't know what other car would fit the bill. Placing these two rare cars into the game was like adding a complex taste, if my bento box metaphor were appropriate. They might not be appreciated or even acknowledged by gamers but they were unique choices that helped make the game stand out.

Auto Modellista offered tremendous originality, glimpses at courses and experiences that were uniquely Japanese. Like most gamers I was put off by the controls and lack of realistic physics applied to the cars. Once I beat the game I went back through it to see what details I had overlooked. It was at that point that I discovered how much work Capcom had put into the title. Little by little I began unlocking items for my garage. I began spending more and more time setting up my dream layout. Deciding the exact placement of my stereo, toolbox and air compressor. Making sure my trophies were displayed not too discreetly. The various batteries and oil cans sorted into their own shelves. Classic tin signs framing the old racing gloves and helmets on my wall of fame. The garage suddenly had a lived-in feel. Whenever I parked a car in the garage it seemed to fit just right.

Then I went back to the roads and began driving the courses again. I noticed the high speed train running over the bridge in Osaka, as well as the low flying jet in Tokyo. The LOVE sign in Shinjuku. At night the streets belonged to the racers. There were no fans obscuring the sidelines, especially not in the rain. The lens blur effect from the headlamps, small rooster tails shot up by wheels and speed lines applied by the graphics engine made the experience feel more intimate. It was about the cars and the road, not the spectacle of professional racing. It was the experience of driving reduced to the most important components. A player that was in tune with their car knew how hard they could push it on turns, where the best lines were on the road and how to move through the gears. They could appreciate the experience of driving, absorb the details from the environment and the challenge of overtaking opponents in the middle of a race. Players were expected to live in these moments and internalize them, to make the races as individual as Garage Life mode.

None of the courses were more inspiring than Akagi Hill. Going from sea level to almost 5000 feet in elevation in just over 12 miles Mt. Akagi had been the site of numerous road races, bicycle races and trail marathons. It had been featured before on games like Initial D and other racing games based in Japan. It never looked as memorable as it did in Auto Modellista. The eternal autumn that painted the mountain orange. The strong shadows cast on the road by overhanging trees. The bright leaves on the ground that could be kicked up by the cars. The setting sun that blinded some of the turns. This course was like a snapshot, a moment frozen in time. These were the best sports cars of a generation on one of Japan's most memorable roads. The beauty of car and course would be preserved forever in Auto Modellista. Only those that took a moment to appreciate the splendor of the course would understand what Capcom was trying to capture.

Auto Modellista never became the franchise that Capcom wanted it to be. Who knows where the series would have taken players if only it had done better? In the rush to complete the title as fast as possible most gamers never gave it a fair chance. The experience of Auto Modellista was more esoteric than players were used to. They tuned cars, raced them and won trophies as they had dozens of times earlier. Because of the brevity of courses and lackluster gameplay the entirety of Auto Modellista was panned. Playing as a car designer was what gamers missed. To appreciate the beautiful coexistence man and machine the player had to be willing to put more time into the game. Passing through the title was simply not good enough. To grasp the experience that Capcom was going for a player had to invest more time in the garage and more miles on the road. The only thing that would be remembered by gamers were the visuals. No racing game before or since had colored the genre so profoundly. The look of the original PS2 and Xbox release continued to inspire, even at the dawn of the PS4 and Xbox 720. The gamer that gave up on Auto Modellista without giving the entire experience a thorough chance was ultimately the racer that lost.

No comments:

Post a Comment