In 2002 Pipeworks software developed Godzilla: Destroy All Monsters Melee. The game had several modes of play and featured a pretty good cast of Toho monsters, and even a few variations of Godzilla from the different movie eras. Pipeworks allowed audiences to settle into the universe with a story mode. An alien invasion had spurred Godzilla and his monster allies to defend the Earth. Players were taken to highly detailed cities all around the world to battle the forces of evil. The game was in 3D and had far mode advanced visuals than the previous Dreamcast game. Buildings had more realistic physics applied to them, better textures and lighting as well. All of the details for each monster were preserved, including the various roars and special attacks. These abilities became part of the game play.

Players could roam each arena in any direction and fight with an assortment of close and ranged attacks. The characters had grappling moves and combos on top of the regular attacks. The diversity of moves made it one of the most robust giant monster games ever created. The amount of detail placed on the levels was absurdly high. Traffic moved on the streets, neon billboards blinked, buildings were lit from the inside, strike fighters shot missiles, tanks fired artillery shells and UFOs zapped monsters with laser beams. An announcer broadcast the outcome of each battle to the world media. Players could roam each arena in any direction, hide from incoming attacks, knock down buildings and fight with an assortment of close and ranged attacks. The borders of each level were cordoned off by bright laser beams that could injure opponents. Destroy All Monsters Melee could be considered a 3D version of King of the Monsters. There were a couple of things holding back the game however.

The monsters moved sluggishly, the camera was not always cooperative and the combat system was not well balanced. A good 3D fighting game like Tobal No. 1, or 3D arena fighter like Power Stone or even 3D brawler like Urban Reign figured out that the levels, camera and combat had to compliment each other. If any element were ignore then the entire experience would suffer. When playing in 3D it was paramount that the player be able to move where they wanted to while still being able to keep enemies in frame. The camera seemed to pivot randomly in Destroy All Monsters Melee, sometimes being blocked out by a tall building and other times floating high above the action. This random camera could be troublesome during a heated battle. The studio tried to fix the camera by allowing buildings to become transparent to show which characters were behind them, however the other buildings between opponents were solid and offered no line of sight. The game had items to regenerate health and power up attacks randomly pop up all around stages. Players often found themselves making a run for the item only to have the camera rotate in the opposite direction and hide it behind a building. The split second that it took the player to reorient themselves was enough for the opponent to snatch up the item. It could be maddening when trying to finish a close battle.

Pipeworks tried again and again to do the genre justice. Godzilla Save the Earth was released in 2004 and Godzilla Unleashed in 2007. In 2006 the same studio had also released Rampage Total Destruction. Their attempts at owning the giant monster genre fell flat with many gamers and reviewers especially. Only the die-hard monster fans, or young boys seemed to enjoy the series. If the studio had one thing going in their favor was the addition of multiple two-player mini games. Each successive Godzilla added new modes of game play which were refreshing. Players could spend time throwing buildings at Naval assaults, play kaiju bowling (which was more like dodgeball really) or even swim underwater as Godzilla. To be fair the games also had another thing going for them, playing as different characters resulted in having different story modes play out as well. But these game play additions were on top of an average experience.

The studio appeared obsessed with trying to put in as many daikaiju characters as they could and didn't bother to spend any time balancing the combat system, adjusting the sluggish control or fixing the camera. The studio would have fans vote on which characters they wanted to see in the next game and then try to secure the rights to those characters. They would appeal to the fans on giant monster fan boards to get the vote out. Moving according to popularity vote was something for American Idol and not a respectable game developer. Focusing on fanservice rather than game play was the antithesis of good game design, yet that seemed to be the goal of the company. The review scores reflected their decision accordingly. On a 10 point scale with 10 being the highest here were what some reviewers gave Godzilla Unleashed; Game Informer: 4, GameSpot: 3.5, GameTrailers: 5, IGN: 4.9 and Nintendo Power: 5.5.

The Godzilla games looked great but played poorly. They were far too sluggish to be enjoyed by most audiences. Pipeworks did a mediocre job in convincing players that they were controlling massive creatures. Godzilla moved slowly in the films for several reasons. In canon Godzilla only appeared to move slowly but actually reacted quite rapidly. He could cover miles in a few seconds. There were two practical reasons why the character moved slowly in real life though. Part of it was for dramatic tension. Human characters trapped in the same city occupied by Godzilla were constantly in danger. The slower the character moved the longer the tension could built up on the big screen. Cloverfield used this understanding equally well. The other reason Godzilla moved slowly was because of the set up time that it took for each movie shot. Model cities took months to build and ate up the majority of the film budget. If the person wearing the Godzilla costume walked in a regular human stride then he could cross a warehouse-sized set in a few seconds. All of those models would have been wasted if they were on screen for only a moment.

Instead the costumed actor would move slowly and allow miniature missiles to be launched at him. The pyrotechnics engineers could then explode the models as he walked through, making for a many more interesting shots. In the Godzilla games the characters were slow and cumbersome because that was how Pipeworks programmed them. They did not convince players that the characters had any sort of mass. The could instead bounce, twirl and be thrown about as if they were Styrofoam-filled mannequins.

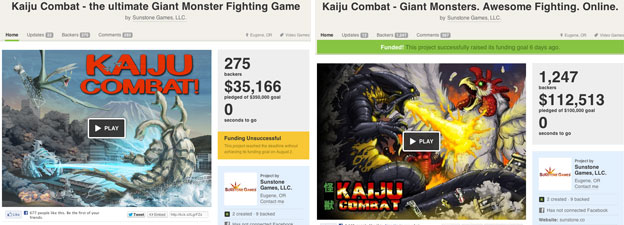

The control and combat designer for the Godzilla games, Simon Strange, left to start his own company. His newly formed Sunstone Games wanted to make the ultimate online giant monster battle game. They wanted to allow players to design their own creatures and give them unique powers as well as include every possible daikaiju ever, including those from Toho's rival studios. They appealed to the public through Kickstarter to help sponsor Kaiju Combat. I had learned about this pitch early on but decided not to publicize it on my blog. I felt that the Godzilla titles Mr. Strange had worked on were visually impressive but offered nothing for gamers. It seemed that the audiences themselves let Sunstone know by not supporting their ambitious goal. They had to run the Kickstarter campaign twice. Earlier in 2012 the studio was looking to secure $350K in funding but managed to get only $35K worth of pledges. They tried again later that year and lowered the investment to $100K. They barely managed to get over the goal with $112K and over 1200 backers.

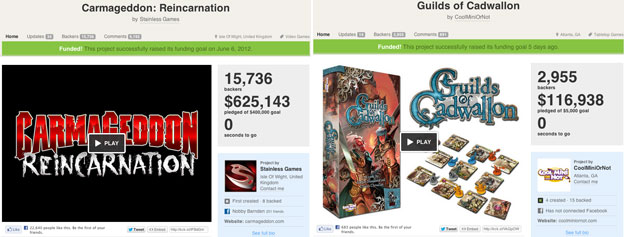

To put the demand for a kaiju game by Sunstone in perspective compare it to other Kickstarter projects for independent studios. Stainless Software had only developed 2 Carmageddon games for the PC and Mac. It had been 15 years since their last Carmageddon title. Stainless ran a Kickstarter campaign looking to get $400K in backing in the same one month window that every studio got. They managed to secure $625K and over 15,000 pledges. That wasn't even a record for a game. One of the biggest success stories on Kickstarter was a card-based game set in the IP of the now defunct Rackham Studios universe. The Guilds of Cadwallon was trying to get $5000 in backing and raised over $116K in a month. A card based game based on an expired French tabletop system had raised more funding than a giant monster video game with a high profile track record attached to it. Why did this happen? The damage to the daikaiju genre had been done thanks in part to the Pipeworks series. Carmageddon and Cadwallion were much more enjoyable experiences and had less flaws to their game play. When those developers needed funding then more than enough people were willing to help them out.

The difference between funding three different types of games was in the game play experience and not popularity. Godzilla had millions of followers the world over, far more than Carmageddon or Cadwallon combined. The character could sell almost anything on name alone. Yet great gaming experiences always seemed to elude the creature. Pipeworks had four giant monster releases; three Godzilla titles and one Rampage game, each one was reviewed worse than the previous. Had Pipeworks delivered a great experience again and again then there would not be a doubt that a publisher would have funded an online project. In fact if the genre as a whole had a better track record then any number of developers, like Capcom or Konami, would have already started work on a daikaiju MMO. Truly great giant monster games were rare, extremely rare, like footage of the elusive giant squid. Gamers wanted to believe that they were out there, they just had to be patient and wait an extraordinarily long time to see one in person. Audiences didn't have the luxury of waiting. Developers couldn't find a way to make a decent gaming experience out of the creatures, so instead the giant monster simply became an obstacle to overcome. It did not stop some developers from trying to work with the genre though. We shall look at some of the hits and misses in the next blog.

No comments:

Post a Comment