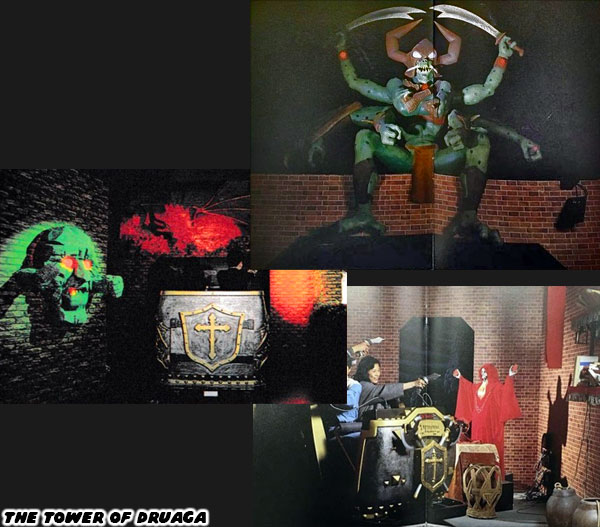

The village calls on

Goddess Elds

for spontaneous play

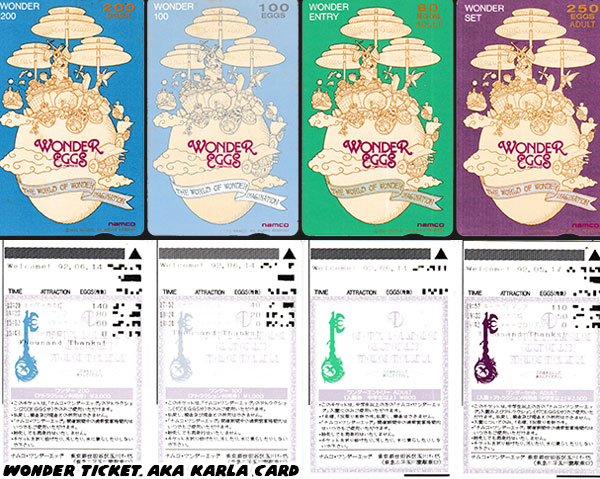

Wonder Eggs, and Egg Empire research collected from: Wonder Eggs Guide Map, Namco Graffiti magazine, the book “All About Namco II", NOURS magazine, The Namco Museum, Namco Wiki, Ge-Yume Area 51 Shigeki Toyama Collection, mcSister magazine, first person attraction details from Yoshiki. Event details from Hole in the Socks

No comments:

Post a Comment