These arrangements with the mob were not only done in the US though. There had been reports of wrestling and Yakuza dealings in Japan as well. This was not limited to modern wrestling though, remember that Rikidozan was stabbed by Yakuza enforcers in a nightclub back in 1954. In Engalnd and Europe some of the criminal elements went hand in hand with boxing and wrestling as well. In 1938 Gerald Kersh had a book published titled Night and the City. It was set in the London underworld and revolved around a petty criminal named Harry Fabian that failed from his get rich schemes again and again. He saw an opening in the pro wrestling game and tried to develop his own talent and compete in the mob ruled underworld. Unfortunately for him all of his choices were the wrong ones and he ended up owing a great debt to the mob at the same time the law was catching up with him. It was a dark story that was turned into a 1950 film by Jules Dassin.

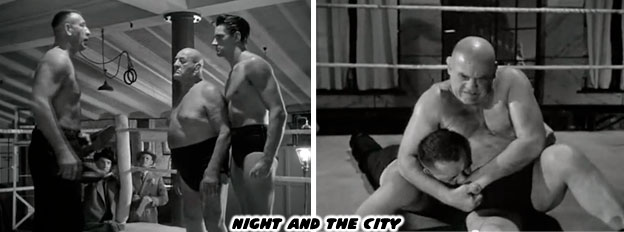

The movie took a lot of liberties with the story and focused more on the relationship between Fabian, as played by Richard Widmark and his young wrestler Nikolas of Athens as played by Ken Richmond. To help the young wrestler get up to par he came across an old Catch wrestler named Gregorius the Great as played by Stanislaus Zbyszko to help train him. Stanislaus was actually Polish, playing a Greek immigrant. The son of Gregorius, Kristo as played by Herbert Lom, ran the mob and controlled the wrestling action. Gregorius was ashamed at the pre-determined spectacle that Greco Roman wrestling had become. Any honor or dignity that the sport and athletes once enjoyed had been stripped away by the mobsters.

In the pivotal scene of the movie a rival wrestler named the Strangler, as played by veteran tough guy Mike Mazurki, goaded Gregorius into fighting him. Stanislaus was 71-years-old when the scene was shot. Despite his age it was a convincing battle between the two grapplers. The authenticity of moves highlighted by the former champion helped the credibility of the fight. After dispatching the Strangler the elder Gregorius turned to his son and uttered the best line in the movie "that's what I do to your clowns." The scene had tremendous weight because Stanislaus was speaking as a real-life Gregorius. A lower quality version of the fight scene with the tragic outcome could be found on YouTube.

Catch wrestling never died but it also never gained popularity with the advent of "pro wrestling." Still it managed to survive through most of the 20th century. Thanks to people like Frank Gotch and Stanislaus Zbyszko. There were other pioneers that helped keep it going through the early days. Dan Kolov, the Bulgarian wrestler who emigrated to the US as a railroad worker and fought a bear with his bare hands while out hunting. He killed the bear with his rifle but when people saw the marks Kolov had left on the neck of the bear they knew he would make a formidable wrestler. Kolov might have been one of the legendary figures that inspired the character Zangief in Street Fighter II. Other catch practitioners that popularized the form in the US included Martin "Farmer" Burns, Ed "Strangler" Lewis, "Tiger" John Pesek, Billy Riley and Billy Robinson.

In the modern era there were fighters like Gene Lebell that helped promote Catch as well as other schools of fighting for wrestlers. Frank and Ken Shamrock, Josh Barnett and Randy Couture were MMA superstars that also trained under the Catch style. Kazushi Sakuraba had joined the ranks of fighters that predated the Gracie family. He had managed to make the transition from pro wrestler to MMA superstar without losing his roots. At the same time he was able to incorporate the showmanship he had picked up in pro wrestling and create a memorable character for himself. He often payed homage to the wrestlers that came before like the Great Muta and Big Van Vader.

The Catch wrestler and MMA fighter had started changing the course of character designs before Tendo Gai however. The next blog will look at the first MMA star that Capcom had created for the Street Fighter universe. As always if you enjoyed this blog and would like to sponsor me please visit my Patreon page and consider donating each month, even as little as $1 would help make better blogs and even podcasts!

No comments:

Post a Comment